The Russian Anarchist Movement During the First World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After Makhno – Hidden Histories of Anarchism in the Ukraine

AFTER MAKHNO The Anarchist underground in the Ukraine AFTER MAKHNO in the 1920s and 1930s: Outlines of history By Anatoly V. Dubovik & The Story of a Leaflet and the Pate of SflHflMTbl BGAVT3AC060M the Anarchist Varshavskiy (From the History of Anarchist Resistance to nPM3PflK CTflPOPO CTPOJI Totalitarianism) "by D.I. Rublyov Translated by Szarapow Nestor Makhno, the great Ukranian anarchist peasant rebel escaped over the border to Romania in August 1921. He would never return, but the struggle between Makhnovists and Bolsheviks carried on until the mid-1920s. In the cities, too, underground anarchist networks kept alive the idea of stateless socialism and opposition to the party state. New research printed here shows the extent of anarchist opposition to Bolshevik rule in the Ukraine in the 1920s and 1930s. Cover: 1921 Soviet poster saying "the bandits bring with them a ghost of old regime. Everyone struggle with banditry!" While the tsarist policeman is off-topic here (but typical of Bolshevik propaganda in lumping all their enemies together), the "bandit" probably looks similar to many makhnovists. Anarchists in the Gulag, Prison and Exile Project BCGHABOPbBV Kate Sharpley Library BM Hurricane, London, WC1N 3 XX. UK C BftHflMTMSMOM! PMB 820, 2425 Channing Way, Berkeley CA 94704, USA www.katesharpleylibrary.net Hidden histories of Anarchism in the Ukraine ISBN 9781873605844 Anarchist Sources #12 AFTER MAKHNO The Anarchist underground in the Ukraine in the 1920s and 1930s: Outlines of history By Anatoly V. Dubovik & The Story of a Leaflet and the Pate of the Anarchist Varshavskiy (From the History of Anarchist Resistance to Totalitarianism) "by D.I. -

Rancour's Emphasis on the Obviously Dark Corners of Stalin's Mind

Rancour's emphasis on the obviously dark corners of Stalin's mind pre- cludes introduction of some other points to consider: that the vozlzd' was a skilled negotiator during the war, better informed than the keenly intelli- gent Churchill or Roosevelt; that he did sometimes tolerate contradiction and even direct criticism, as shown by Milovan Djilas and David Joravsky, for instance; and that he frequently took a moderate position in debates about key issues in the thirties. Rancour's account stops, save for a few ref- erences to the doctors' plot of 1953, at the end of the war, so that the enticing explanations offered by William McCagg and Werner Hahn of Stalin's conduct in the years remaining to him are not discussed. A more subtle problem is that the great stress on Stalin's personality adopted by so many authors, and taken so far here, can lead to a treatment of a huge country with a vast population merely as a conglomeration of objects to be acted upon. In reality, the influences and pressures on people were often diverse and contradictory, so that choices had to be made. These were simply not under Stalin's control at all times. One intriguing aspect of the book is the suggestion, never made explicit, that Stalin firmly believed in the existence of enemies around him. This is an essential part of the paranoid diagnosis, repeated and refined by Rancour. If Stalin believed in the guilt, in some sense, of Marshal Tukhachevskii et al. (though sometimes Rancour suggests the opposite), then a picture emerges not of a ruthless dictator coldly plotting the exter- mination of actual and potential opposition, but of a fear-ridden, tormented man lashing out in panic against a threat he believed to real and immediate. -

Nestor Makhno in the Russian Civil War.Pdf

NESTOR MAKHNO IN THE RUSSIAN CIVIL WAR Michael Malet THE LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE TeutonicScan €> Michael Malet \982 AU rights reserved. No parI of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, wilhom permission Fim ed/lIOn 1982 Reprinted /985 To my children Published by lain, Saffron, and Jonquil THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London rind BasingSloke Compafl/u rind reprutntatiW!S throughout the warld ISBN 0-333-2S969-6 Pnnted /II Great Bmain Antony Rowe Ltd, Ch/ppenham 5;landort � Signalur RNB 10043 Akz.·N. \d.·N. I, "'i • '. • I I • Contents ... Acknowledgements VIII Preface ox • Chronology XI .. Introduction XVII Glossary xx' PART 1 MILITARY HISTORY 1917-21 1 Relative Peace, 1917-18 3 2 The Rise of the Balko, July 19I5-February 1919 13 3 The Year 1919 29 4 Stalemate, January-October 1920 54 5 The End, October I92O-August 1921 64 PART 2 MAKHNOVSCHYNA-ORGAN1SATION 6 Makhno's Military Organisation and Capabilities 83 7 Civilian Organisation 107 PART 3 IDEOLOGY 8 Peasants and Workers 117 9 Makhno and the Bolsheviks 126 10 Other Enemies and Rivals 138 11 Anarchism and the Anarchists 157 12 Anti-Semitism 168 13 Some Ideological Questions 175 PART 4 EXILE J 4 The Bitter End 183 References 193 Bibliography 198 Index 213 • • '" Acknowledgements Preface My first thanks are due to three university lecturers who have helped Until the appearance of Michael PaJii's book in 1976, the role of and encouraged me over the years: John Erickson and Z. A. B. Nestor Makhno in the events of the Russian civil war was almost Zeman inspired my initial interest in Russian and Soviet history, unknown. -

Bakunin and the Psychobiographers

BAKUNIN AND THE PSYCHOBIOGRAPHERS: THE ANARCHIST AS MYTHICAL AND HISTORICAL OBJECT Robert M. Cutler Email: [email protected] Senior Research Fellow Institute of European, Russian and Eurasian Studies Carleton University Postal address: Station H, Box 518 Montreal, Quebec H3G 2L5 Canada 1. Introduction: The Psychological Tradition in Modern Bakunin Historiography 2. Key Links and Weak Links: Bakunin's Relations with Marx and with Nechaev 3. Lessons for the Marriage of Psychology to History 3.1. Historical Method, or Kto Vinovat?: Problems with the Use of Sources in Biography 3.2. Psychological Method, or Chto Delat'?: Problems with Cultural Context and the Individual 4. Conclusion: Social Psychology, Psychobiography, and Mythography 4.1. Social Psychology at the Crossroads of Character and Culture 4.2. Psychobiography to Social Psychology: A Difficult Transition 4.3. Mythography and Its Link to Social Psychology: The Contemporary Relevance of Bakunin Historiography English original of the Russian translation in press in Klio (St. Petersburg) Available at http://www.robertcutler.org/bakunin/pdf/ar09klio.pdf Copyright © Robert M. Cutler . 1 BAKUNIN AND THE PSYCHOBIOGRAPHERS: THE ANARCHIST AS MYTHICAL AND HISTORICAL OBJECT Robert M. Cutler Biographies typically rely more heavily upon personal documents than do other kinds of history, but subtleties in the use of such documents for psychological interpretation have long been recognized as pitfalls for misinterpretation even when contemporaries are the subject of study. Psychobiography is most persuasive and successful when its hypotheses and interpretations weave together the individual with broader social phenomena and unify these two levels of analysis with any necessary intermediate levels. However, in practice psychobiography rarely connects the individual with phenomena of a social-psychological scale.1 Psychobiography is probably the only field of historical study more problematic than psychohistory in general, principally because questions of interpretation are so much more difficult. -

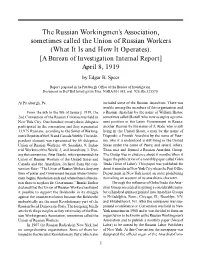

The Russian Workingmen's Association, Sometimes Called The

Speer: History of the Union of Russian Workers [April 8, 1919] 1 The Russian Workingmen’s Association, sometimes called the Union of Russian Workers (What It Is and How It Operates). [A Bureau of Investigation Internal Report] April 8, 1919 by Edgar B. Speer Report prepared in he Pittsburgh Office of the Bureau of Investigation. Document in DoJ/BoI Investigative Files, NARA M-1085, reel. 926, file 325570. At Pittsburgh, Pa. included some of the Russian Anarchists. There was trouble among the members of this organization and From the 6th to the 9th of January, 1919, the a Russian Anarchist by the name of William Shatov, 2nd Convention of the Russian Colonies was held in sometimes called Shatoff, who now occupies a promi- New York City. One hundred twenty-three delegates nent position in the Lenin Government in Russia; participated in the convention and they represented another Russian by the name of A. Rode, who is still 33,975 Russians, according to the Soviet of Working- living in the United States; a man by the name of men’s Deputies of the US and Canada Weekly. The inde- Dieproski; a Finnish Anarchist by the name of Peter- pendent element was represented by 60 delegates; son, who it is understood is still living in the United Union of Russian Workers, 49; Socialists, 9; Indus- States under the name of Peters; and several others. trial Workers of the World, 2; and Anarchists, 3. Dur- These met and formed a Russian Anarchist Group. ing the convention, Peter Bianki, who represented the The Group was in existence about 6 months when it Union of Russian Workers of the United States and began the publication of a monthly paper called Golos Canada and the Anarchists, declared from the con- Truda (Voice of Labor). -

Ursula Mctaggart

RADICALISM IN AMERICA’S “INDUSTRIAL JUNGLE”: METAPHORS OF THE PRIMITIVE AND THE INDUSTRIAL IN ACTIVIST TEXTS Ursula McTaggart Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Departments of English and American Studies Indiana University June 2008 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Purnima Bose, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ Margo Crawford, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ DeWitt Kilgore ________________________________ Robert Terrill June 18, 2008 ii © 2008 Ursula McTaggart ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A host of people have helped make this dissertation possible. My primary thanks go to Purnima Bose and Margo Crawford, who directed the project, offering constant support and invaluable advice. They have been mentors as well as friends throughout this process. Margo’s enthusiasm and brilliant ideas have buoyed my excitement and confidence about the project, while Purnima’s detailed, pragmatic advice has kept it historically grounded, well documented, and on time! Readers De Witt Kilgore and Robert Terrill also provided insight and commentary that have helped shape the final product. In addition, Purnima Bose’s dissertation group of fellow graduate students Anne Delgado, Chia-Li Kao, Laila Amine, and Karen Dillon has stimulated and refined my thinking along the way. Anne, Chia-Li, Laila, and Karen have devoted their own valuable time to reading drafts and making comments even in the midst of their own dissertation work. This dissertation has also been dependent on the activist work of the Black Panther Party, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, the International Socialists, the Socialist Workers Party, and the diverse field of contemporary anarchists. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

Ak Press Summer 2010 Catalog

ak press summer 2010 catalog AK PRESS 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612 www.akpress.org WELCOME TO THE 2010 SUMMER SUPPLEMENT! Hello dear readers, About AK Press. ............................ 3 History .......................................... 17 Acerca de AK Press ..................... 4 Kids ............................................... 19 Thanks for picking up the most recent AK Friends of AK Press ...................... 28 Labor ............................................ 19 Press catalog! This is our Summer 2010 Media ........................................... 19 supplement; in it, you’ll find all of the new AK Press Publishing Non-Fiction.................................. 19 items we’ve received (or published) in the New Titles....................................... 5 Poetry ........................................... 21 past six months ... it’s all great stuff, and Politics/Current Events ............. 21 you’re sure to find a ton of items you’ll want Forthcoming ................................... 6 Recent & Recommended ............. 8 Prisons/Policing ......................... 22 to grab for yourself or for your friends and Punk.............................................. 22 family. But, don’t forget: this is only a small AK Press Distribution Race ............................................. 22 sampling of the great stuff we have to offer! Situationist .................................. 23 For our complete and up-to-date listing of Spanish ........................................ 23 thousands more books, CDs, pamphlets, -

On the History of Mystical Anarchism in Russia V

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 20 | Issue 1 Article 9 1-1-2001 On the History of Mystical Anarchism in Russia V. V. Nalimov Moscow State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Nalimov, V. V. (2001). Nalimov, V. V. (2001). On the history of mystical anarchism in Russia. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 20(1), 85–98.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 20 (1). http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24972/ ijts.2001.20.1.85 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. On the History of Mystical Anarchism in Russia V. V. Nalimov Moscow State University Moscow, Russia Translated from the Russian by A. V Yarkho T SEEMS that the time is ripe to write about existing regime was regarded by many as a the subject of Mystical Anarchism. It is not a natural and unavoidable historical event. The I simple subject to discuss. It is rooted in the important thing was that the fight for freedom remotest past of Gnostic Christianity and even should not turn into a new nonfreedom. perhaps earlier (according to the legend) in At the end of the 1920s, among some of the Ancient Egypt. -

To What Extent Was Makhno Able to Implement Anarchist Ideals During the Russian Civil War?

Library.Anarhija.Net To what extent was Makhno able to implement anarchist ideals during the Russian Civil War? Kolbjǫrn Markusson Kolbjǫrn Markusson To what extent was Makhno able to implement anarchist ideals during the Russian Civil War? no date provided submitted by anonymous without source lib.anarhija.net no date provided Contents Bibliography ......................... 12 2 Born on October 26 (N.S. November 7) 1888 in Gulyai-Polye, Ukraine, Nestor Ivanovych Makhno was a revolutionary anarchist and the most well-known ataman (commander) of the Revolution- ary Insurgent Army of the Ukraine during the Russian Civil War.1 Historiographical issues regarding the extent to which Makhno and the Makhnovists implemented anarchist ideals in south-east Ukraine have been noted by contemporary Russian anarchist and historian Peter Arshinov. Makhno’s own memoirs and the newspa- per Put’ k Svobode, both valuable material documenting anarchist activity in Ukraine, were lost during the Civil War.2 With much of the contemporary evidence impossible to reconstruct, historians have attempted to understand the nature of the Makhnovist move- ment and the ‘social revolution’ in Ukraine with surviving evidence whilst separating myth and legend about Makhno from historical fact. This essay will argue that Makhno and the Makhnovist move- ment were inspired by anarchist ideals in an attempt to establish a ‘free and completely independent soviet system of working people without authorities’ during the Civil War.3 However, the war itself hindered the political and economic development of the anarchist ‘free territory’ before finally being defeated and dissolved by the Bolshevik-led Red Army in August 1921. -

Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917–21 Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917–21

Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917–21 Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917–21 Colin Darch First published 2020 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Colin Darch 2020 The right of Colin Darch to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3888 0 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3887 3 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7868 0526 3 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0528 7 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0527 0 EPUB eBook Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England For my grandchildren Historia scribitur ad narrandum, non ad probandum – Quintilian Contents List of Maps viii List of Abbreviations ix Acknowledgements x 1. The Deep Roots of Rural Discontent: Guliaipole, 1905–17 1 2. The Turning Point: Organising Resistance to the German Invasion, 1918 20 3. Brigade Commander and Partisan: Makhno’s Campaigns against Denikin, January–May 1919 39 4. Betrayal in the Heat of Battle? The Red–Black Alliance Falls Apart, May–September 1919 54 5. The Long March West and the Battle at Peregonovka 73 6. Red versus White, Red versus Green: The Bolsheviks Assert Control 91 7. The Last Act: Alliance at Starobel’sk, Wrangel’s Defeat, and Betrayal at Perekop 108 8. The Bitter Politics of the Long Exile: Romania, Poland, Germany, and France, 1921–34 128 9. -

Bakunin and the United States

PA UL A VRICH BAKUNIN AND THE UNITED STATES "MIKHAIL ALEKSANDROVICH BAKUNIN is in San Francisco", announced the front page of Herzen's Kolokol in November 1861. "HE IS FREE! Bakunin left Siberia via Japan and is on his way to England. We joyfully bring this news to all Bakunin's friends."1 Arrested in Chemnitz in May 1849, Bakunin had been extradited to Russia in 1851 and, after six years in the Peter-Paul and Schlusselburg fortresses, condemned to per- petual banishment in Siberia. On June 17, 1861, however, he began his dramatic escape. Setting out from Irkutsk, he sailed down the Amur to Nikolaevsk, where he boarded a government vessel plying the Siberian coast. Once at sea, he transferred to an American sailing ship, the Vickery, which was trading in Japanese ports, and reached Japan on August 16th. A month later, on September 17th, he sailed from Yokohama on another American vessel, the Carrington, bound for San Francisco.2 He arrived four weeks later,3 completing, in Herzen's description, "the very longest escape in a geographical sense".4 Bakunin was forty-seven years old. He had spent the past twelve years in prison and exile, and only fourteen years of life — extremely active life, to be sure — lay before him. He had returned like a ghost from the past, "risen from the dead" as he wrote to Herzen and Ogarev from San Francisco.5 His sojourn in America, one of the least well-known episodes of his career, lasted two months, from October 15th, when he landed in San Francisco, to 1 Kolokol (London), November 22, 1861.