Chapter Twenty One Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

Verdi Falstaff

Table of Opera 101: Getting Ready for the Opera 4 A Brief History of Western Opera 6 Philadelphia’s Academy of Music 8 Broad Street: Avenue of the Arts Con9tOperae Etiquette 101 nts 10 Why I Like Opera by Taylor Baggs Relating Opera to History: The Culture Connection 11 Giuseppe Verdi: Hero of Italy 12 Verdi Timeline 13 Make Your Own Timeline 14 Game: Falstaff Crossword Puzzle 16 Bard of Stratford – William Shakespeare 18 All the World’s a Stage: The Globe Theatre Falstaff: Libretto and Production Information 20 Falstaff Synopsis 22 Meet the Artists 23 Introducing Soprano Christine Goerke 24 Falstaff LIBRETTO Behind the Scenes: Careers in the Arts 65 Game: Connect the Opera Terms 66 So You Want to Sing Like an Opera Singer! 68 The Highs and Lows of the Operatic Voice 70 Life in the Opera Chorus: Julie-Ann Whitely 71 The Subtle Art of Costume Design Lessons 72 Conflicts and Loves in Falstaff 73 Review of Philadelphia’s First Falstaff 74 2006-2007 Season Subscriptions Glossary 75 State Standards 79 State Standards Met 80 A Brief History of 4 Western Opera Theatrical performances that use music, song Music was changing, too. and dance to tell a story can be found in many Composers abandoned the ornate cultures. Opera is just one example of music drama. Baroque style of music and began Claudio Monteverdi In its 400-year history opera has been shaped by the to write less complicated music 1567-1643 times in which it was created and tells us much that expressed the character’s thoughts and feelings about those who participated in the art form as writers, more believably. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) Russianness in the Works of European Composers Liudmila Kazantseva Department of Theory and History of Music Astrakhan State Concervatoire Astrakhan, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—For the practice of composing a conscious Russianness is seen more as an exotic). As one more reproduction of native or non-native national style is question I’ll name the ways and means of capturing Russian traditional. As the object of attention of European composers origin. are constantly featured national specificity of Russian culture. At the same time the “hit accuracy” ranges here from a Not turning further on the fan of questions that determine maximum of accuracy (as a rule, when finding a composer in the development of the problems of Russian as other- his native national culture) to a very distant resemblance. The national, let’s focus on only one of them: the reasons which out musical and musical reasons for reference to the Russian encourage European composers in one form or another to culture they are considered in the article. Analysis shows that turn to Russian culture and to make it the subject of a Russiannes is quite attractive for a foreign musicians. However creative image. the European masters are rather motivated by a desire to show, to indicate, to declare the Russianness than to comprehend, to II. THE OUT MUSICAL REASONS FOR REFERENCE TO THE go deep and to get used to it. RUSSIAN CULTURE Keywords—Russian music; Russianness; Western European In general, the reasons can be grouped as follows: out composers; style; polystyle; stylization; citation musical and musical. -

12:00:00A 00:00 Jueves, 9 De Noviembre De 2017 12A NO - Nocturno 12:00:00A 03:12 Sonata P/Piano Y Violín Op.5 En Sol May

*Programación sujeta a cambios sin previo aviso* JUEVES 09 DE NOVIEMBRE 2017 12:00:00a 00:00 jueves, 9 de noviembre de 2017 12A NO - Nocturno 12:00:00a 03:12 Sonata p/piano y violín op.5 en Sol May. Jan Vaclav Vorisek (1791-1825) Ivan Klansky-piano; Cenek Pavlik-violín 12:27:12a 19:08:00 *La paloma del bosque Op.110, Poema sinfónico Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904) Jiri Belohlavek Filarmónica Checa 12:46:20a 09:50 Concierto p/cuerdas no.4 en Mi Bem.May. John Hebden (1712-1765) Adrien Shepherd Cantilena 12:56:10a 00:50 Identificación estación 01:00:00a 00:00 jueves, 9 de noviembre de 2017 1AM NO - Nocturno 01:00:00a 17:30 Suite Catfish row, con escenas de "Porgy and Bess" George Gershwin (1898-1937) Michael Tilson Thomas Sinfónica de San Francisco Audra McDonald-sop.; Brian Stokes-bar. 01:41:30a 12:37:00 Serenata no.3 op.69 en re men. Robert Volkmann (1815-1883) Karl Ludwig Nicol Miemb. Sinf. Radio Bávara 01:54:07a 00:50 Identificación estación 02:00:00a 00:00 jueves, 9 de noviembre de 2017 2AM NO - Nocturno 02:00:00a 06:00 Sonata V en re men. Carlos de Seixas (1704-1742) Sophie Yates-clavecín 02:06:00a 07:30 Cuarteto p/piano y cuerdas no.1 op.15 en do men. Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Emmanuel Ax; Isaac Stern; Jaime Laredo; Yo-Yo Ma 02:37:30a 15:19:00 Concierto p/violín y orq. op.3 no.9 en Sol May. Pietro Antonio Locatelli (1695-1764) Nicholas Kraemer The Raglan Baroque Players Elizabeth Wallfisch-violín 02:52:49a 00:50 Identificación estación 03:00:00a 00:00 jueves, 9 de noviembre de 2017 3AM NO - Nocturno 03:00:00a 17:36 Sonata para piano no.3 Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) Glenn Gould-piano 03:17:36a 01:06 Cuarteto no.2 "Cartas intimas" (1928) Leos Janacek (1854-1928) Cuarteto Melos 03:42:42a 10:54:00 El amanecer de la eternidad John Tavener (1944- ) Paul Goodwin Academia de la música antigua Patricia Rozario-soprano 03:53:36a 00:50 Identificación estación 04:00:00a 00:00 jueves, 9 de noviembre de 2017 4AM NO - Nocturno 04:00:00a 09:20 Confluencia Rolando Budini Cuar. -

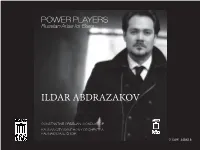

Ildar Abdrazakov

POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR KAUNAS CITY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA KAUNAS STATE CHOIR 1 0 13491 34562 8 ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL iconic characters The dynamics of power in Russian opera and its most DE 3456 (707) 996-3844 • © 2013 Delos Productions, Inc., © 2013 Delos Productions, 95476-9998 CA Sonoma, 343, Box P.O. (800) 364-0645 [email protected] www.delosmusic.com CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR ORBELIAN, CONSTANTINE ORCHESTRA CITY SYMPHONY KAUNAS CHOIR STATE KAUNAS Arias from: Arias Rachmaninov: Aleko the Tsar & Ludmila,Glinka: A Life for Ruslan Igor Borodin: Prince Boris GodunovMussorgsky: The Demon Rubinstein: Onegin, Iolanthe Eugene Tchaikovsky: Peace and War Prokofiev: Rimsky-Korsakov: Sadko 66:49 Time: Total Russian Arias for Bass ABDRAZAKOV ILDAR POWER PLAYERS ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV 1. Sergei Rachmaninov: Aleko – “Ves tabor spit” (All the camp is asleep) (6:19) 2. Mikhail Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “Farlaf’s Rondo” (3:34) 3. Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “O pole, pole” (Oh, field, field) (11:47) 4. Alexander Borodin: Prince Igor – “Ne sna ne otdykha” (There’s no sleep, no repose) (7:38) 5. Modest Mussorgsky: Boris Godunov – “Kak vo gorode bylo vo Kazani” (At Kazan, where long ago I fought) (2:11) 6. Anton Rubinstein: The Demon – “Na Vozdushnom Okeane” (In the ocean of the sky) (5:05) 7. Piotr Tchaikovsky: Eugene Onegin – “Liubvi vsem vozrasty pokorny” (Love has nothing to do with age) (5:37) 8. Tchaikovsky: Iolanthe – “Gospod moi, yesli greshin ya” (Oh Lord, have pity on me!) (4:31) 9. -

Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century Joshua J

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2016 yS mposium Apr 20th, 3:40 PM - 4:00 PM Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century Joshua J. Taylor Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Musicology Commons Taylor, Joshua J., "Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century" (2016). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 4. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2016/podium_presentations/4 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century What does it mean to be Russian? In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Russian nobility was engrossed with French culture. According to Dr. Marina Soraka and Dr. Charles Ruud, “Russian nobility [had a] weakness for the fruits of French civilization.”1 When Peter the Great came into power in 1682-1725, he forced Western ideals and culture into the very way of life of the aristocracy. “He wanted to Westernize and modernize all of the Russian government, society, life, and culture… .Countries of the West served as the emperor’s model; but the Russian ruler also tried to adapt a variety of Western institutions to Russian needs and possibilities.”2 However, when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Russia in 1812, he threw the pro- French aristocracy in Russia into an identity crisis. -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

Jan 25 to 31.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST January 25 - 31, 2021 PLAY DATE: Mon, 01/25/2021 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 10 "La Caccia" 6:11 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 22 6:30 AM Claudio Monteverdi Madrigals Book 6: Qui rise, o Tirso 6:39 AM Henry Purcell Sonata No. 9 6:48 AM Franz Ignaz Beck Sinfonia 7:02 AM Francois Francoeur Cello Sonata 7:13 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Twelve Variations on a Minuet by Fischer 7:33 AM Alessandro Scarlatti Sinfonia di Concerto Grosso No. 2 7:41 AM Franz Danzi Horn Concerto 8:02 AM Johann Sebastian Bach Lute Suite No. 1 8:17 AM William Boyce Concerto Grosso 8:30 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony No. 8 9:05 AM Lowell Liebermann Piano Concerto No. 2 9:34 AM Walter Piston Divertimento 9:49 AM Frank E. Churchill/Ann Ronell Medley From Snow White & the 7 Dwarfs 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Eight Variations on "Laat ons Juichen, 10:07 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 15 10:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Violin Sonata No. 17 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento No. 9 10:50 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Rondo for piano & orch 11:01 AM Louise Farrenc Quintet for piano, violin, viola, cello 11:31 AM John Alan Rose Piano Concerto, "Tolkien Tale" 12:00 PM Edward MacDowell Hamlet and Ophelia (1885) 12:15 PM Josef Strauss Music of the Spheres Waltz 12:26 PM Sir Paul McCartney A Leaf 12:39 PM Frank Bridge An Irish Melody, "The Londonderry Air" 12:49 PM Howard Shore The Return of the King: The Return of 1:01 PM Johannes Brahms Clarinet Quintet 1:41 PM Benjamin Britten Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra 2:00 PM Ferry Muhr Csardas No. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 171 International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2017) M. I. Glinka’s Opera A Life for the Tzar: a Historical- Archaeological Perspective of Research Yevgeniy Levashev State Institute for Art Studies Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Nadezhda Teterina State Institute for Art Studies Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Yelena Shcheboleva State Institute for Art Studies Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The scientific matter, which is associated with (the day of Mikhail Feodorovich Romanov’s coronation at the name of a real historical person, but somewhat the Moscow Kremlin)1 . mythologized folk hero, the peasant Ivan Susanin, has been discussed in many dozens of books and hundreds of articles in When approached superficially, the development of various fields of domestic Humanities. Among them, a action in Glinka’s opera may seem overloaded with blatant significant part of this research is musicology, which is the key contradictions. They were especially visible in the value in the history of Russian music opera masterpiece by sumptuous theatrical productions of the nineteenth century. Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka. The objective of this article consists consequently in an attempt to show how naturally the musical Indeed, the scene of Polish ball, at which a typical figure drama is associated with the creatively comprehended system of Catholic cardinal is present, gives rise to the following of historical facts in the opera “A Life for the Tsar”. perplexing question: how the Polish soldiers, despite the cruel Russian frost, could reach the distant village of Keywords—Opera “A Life for the Tsar”, Ivan Susanin, tsar Domnino without having noticed on their way neither Mikhail Romanov, Russia and Polish-Lithuanian Smolensk, nor Moscow, nor else Yaroslavl’ or Kostroma. -

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the Soothing Melody STAY with US

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the soothing melody STAY WITH US Spacious modern comfortable rooms, complimentary Wi-Fi, 24-hour room service, fitness room and a large pool. Just two miles from Stanford. BOOK EVENT MEETING SPACE FOR 10 TO 700 GUESTS. CALL TO BOOK YOUR STAY TODAY: 650-857-0787 CABANAPALOALTO.COM DINE IN STYLE Chef Francis Ramirez’ cuisine centers around sourcing quality seasonal ingredients to create delectable dishes combining French techniques with a California flare! TRY OUR CHAMPAGNE SUNDAY BRUNCH RESERVATIONS: 650-628-0145 4290 EL CAMINO REAL PALO ALTO CALIFORNIA 94306 Music@Menlo Russian Reflections the fourteenth season July 15–August 6, 2016 D AVID FINCKEL AND WU HAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTORS Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 R ussian Reflections Program Overview 6 E ssay: “Natasha’s Dance: The Myth of Exotic Russia” by Orlando Figes 10 Encounters I–III 13 Concert Programs I–VII 43 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 58 Chamber Music Institute 60 Prelude Performances 67 Koret Young Performers Concerts 70 Master Classes 71 Café Conversations 72 2016 Visual Artist: Andrei Petrov 73 Music@Menlo LIVE 74 2016–2017 Winter Series 76 Artist and Faculty Biographies A dance lesson in the main hall of the Smolny Institute, St. Petersburg. Russian photographer, twentieth century. Private collection/Calmann and King Ltd./Bridgeman Images 88 Internship Program 90 Glossary 94 Join Music@Menlo 96 Acknowledgments 101 Ticket and Performance Information 103 Map and Directions 104 Calendar www.musicatmenlo.org 1 2016 Season Dedication Music@Menlo’s fourteenth season is dedicated to the following individuals and organizations that share the festival’s vision and whose tremendous support continues to make the realization of Music@Menlo’s mission possible.