Arxiv:1706.07545V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 23 Jun 2017 Russell and C-M Diagrams — Magellanic Clouds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

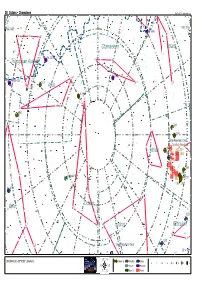

Skytools Chart

38 Octans - Chamaleon SkyTools 3 / Skyhound.com β NGC 6025 NGC 2516 IC 2448 β β ε γ Chamaeleon Volans δ ε ε PK 315-13.1 Triangulum Australe β γ 12h δ2 α ε 3195 ζ PK 325-12.1 1 α ζ 6101 5h η θ δ α Apus 09h 2 IC 4499 γ δ1 β γ ζ 6362 η 2 2210 η 2164 18h 06h Large Magellanic Cloud Tarantula Nebulaδ Mensa 2031 NGC 2014 NGC 1962 NGC 1955 ζ NGC 1874 NGC 1829 θ 1866 κ NGC 1770 1805 Collinder 411 NGC 1814 1978 1818 1783 03h 6744 21h β ε ε γ Octans Pavo ν -80° 00h ν 1559 β α δ θ Hydrus Reticulum β γ ι δ 1313 β Small Magellanic Cloud 0° 52° x 34° -7 ε ζ κ 00h00m00.0s -90°00'00" (Skymark) Globular Cl. Dark Neb. Galaxy 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Globule Planetary Open Cl. Nebula 38 Octans - Chamaleon GALASSIE Sigla Nome Cost. A.R. Dec. Mv. Dim. Tipo Distanza 200/4 80/11,5 20x60 NGC 292 Small Magellanic Cloud Tuc 00h 52m 38s +72° 48' 01” +2,80 318',0x204',0 SBm 0,2 Mly --- --- --- NGC 1313 Ret 03h 18m 15s -66° 29' 51” +9,70 9',5x7',2 Sbcd 13,5 Mly --- --- --- NGC 1559 Ret 04h 17m 36s -62° 47' 01" +11,00 4',2x2',1 SBc 34,0 Mly --- --- --- PGC 17223 Large Magellanic Cloud Dor 05h 23m 35s -69° 45' 22" +0,80 648',0x552',0 SBm 0,2 Mly --- --- --- NGC 6744 Pav 19h 09m 46s -63° 51' 28" +9,10 17',0x10',7 SABb 21,0 Mly --- --- --- AMMASSI APERTI Sigla Nome Cost. -

On the Effects of Subvirial Initial Conditions and the Birth

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 000–000 (0000) Printed 24 October 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) On the Effects of Subvirial Initial Conditions and the Birth Temperature of R136 Daniel P. Caputo1⋆, Nathan de Vries1 and Simon Portegies Zwart1 1Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, the Netherlands 24 October 2018 ABSTRACT We investigate the effect of different initial virial temperatures, Q, on the dynamics of star clusters. We find that the virial temperature has a strong effect on many aspects of the resulting system, including among others: the fraction of bodies escaping from the system, the depth of the collapse of the system, and the strength of the mass segregation. These differences deem the practice of using “cold” initial conditions no longer a simple choice of convenience. The choice of initial virial temperature must be carefully considered as its impact on the remainder of the simulation can be profound. We discuss the pitfalls and aim to describe the general behavior of the collapse and the resultant system as a function of the virial temperature so that a well reasoned choice of initial virial temperature can be made. We make a correction to the previous theoretical estimate for the minimum radius, Rmin, of the cluster at the deepest (−1/3) moment of collapse to include a Q dependency, Rmin ≈ Q+N , where N is the number of particles. We use our numericalresults to infer more aboutthe initial conditions of the young cluster R136. Based on our analysis, we find that R136 was likely formed with a rather cool, but not cold, initial virial temperature (Q ≈ 0.13). -

Gas and Dust in the Magellanic Clouds

Gas and dust in the Magellanic clouds A Thesis Submitted for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Physics To Mangalore University by Ananta Charan Pradhan Under the Supervision of Prof. Jayant Murthy Indian Institute of Astrophysics Bangalore - 560 034 India April 2011 Declaration of Authorship I hereby declare that the matter contained in this thesis is the result of the inves- tigations carried out by me at Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bangalore, under the supervision of Professor Jayant Murthy. This work has not been submitted for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship, etc. of any university or institute. Signed: Date: ii Certificate This is to certify that the thesis entitled ‘Gas and Dust in the Magellanic clouds’ submitted to the Mangalore University by Mr. Ananta Charan Pradhan for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the faculty of Science, is based on the results of the investigations carried out by him under my supervi- sion and guidance, at Indian Institute of Astrophysics. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship, etc. of any university or institute. Signed: Date: iii Dedicated to my parents ========================================= Sri. Pandab Pradhan and Smt. Kanak Pradhan ========================================= Acknowledgements It has been a pleasure to work under Prof. Jayant Murthy. I am grateful to him for giving me full freedom in research and for his guidance and attention throughout my doctoral work inspite of his hectic schedules. I am indebted to him for his patience in countless reviews and for his contribution of time and energy as my guide in this project. -

The Tarantula – Revealed by X-Rays (T-Rex) a Definitive Chandra

TheTarantula{ Revealed byX-rays (T-ReX) A Definitive Chandra Investigation of 30 Doradus Our first impressions of spiral and irregular galaxies are defined by massive star-forming regions (MSFRs), signposts marking spiral arms, bars, and starbursts. They remind us that galaxies really are evolving, churned by the continuous injection of energy and processed material. MSFRs offer us a microcosm of starburst astrophysics, where winds from O and Wolf-Rayet (WR) stars combine with supernovae to carve up the neutral medium from which they formed, both triggering and suppressing new generations of stars. With X-ray observations we see the stars themselves|the engines that shape the larger view of a galaxy|along with the hot, shocked ISM created by massive star feedback, which in turn fills the superbubbles that define starburst clusters (Fig. 1). We propose the 2 Ms Chandra/ACIS-I X-ray Visionary Project T-ReX, an intensive study of 30 Doradus (The Tarantula Nebula) in the LMC, the most powerful MSFR in the Local Group. To date Chandra has invested just 114 ks in this iconic target|proportionally far less than other premier observatories (e.g. HST, VLT, Spitzer, VISTA)|revealing only the most massive stars and large-scale diffuse structures. This very deep observation is essential to engage the great power of Chandra's unparalleled spatial resolution, a unique resource that will remain unmatched for another decade. T-ReX will reveal the X-ray properties of hundreds of 30 Dor's low-metallicity massive stars [1], thousands of lower-mass pre-main sequence (pre-MS) stars that record its star formation history [2], and parsec-scale shocks from winds and supernovae that are shredding its ISM [3,4]. -

Observing List Evening of 2015 Jun 15 at VS Star Party - Gansvlei

James Dunlop's Catalogue (Cozens-150) Observing List Evening of 2015 Jun 15 at VS Star Party - Gansvlei Sunset 17:31, Twilight ends 18:48, Twilight begins 05:41, Sunrise 06:59, Moon rise 06:31, Moon set 16:49 Completely dark from 18:48 to 05:41. New Moon. All times local (GMT+2). Listing All Classes visible above the perfect horizon and in complete darkness after 18:29 and before 06:02. Cls Primary ID Alternate ID Con Mag Size RA 2000 Dec 2000 Distance Begin Optimum End S.A. Ur. 2 PSA Difficulty Gal NGC 2090 MCG -6-13-9 Col 11.5 4.3'x 1.9' 05h47m02.3s -34°15'05" 18:42 18:52 19:06 19 173 18 difficult Neb NGC 2080 ESO 57-EN12 Dor 05h39m42.0s -69°39'00" 18:34 18:54 20:34 24 212 20 unknown Glob NGC 2298 Pup 9.3 5.0' 06h48m59.0s -36°00'18" 98000 ly 18:41 18:57 19:45 19 172 29 detectable Open NGC 2058 Men 11.9 1.8' 05h36m54.3s -70°09'44" 18:41 18:59 20:32 24 212 20 difficult Glob NGC 2164 Dor 10.3 1.7' 05h58m55.6s -68°31'04" 18:37 18:59 21:22 24 212 20 easy Neb NGC 2070 Tarantula Nebula Dor 8.3 5.0' 05h38m36.0s -69°06'00" 18:35 19:00 23:23 24 212 20 obvious Open NGC 2477 Collinder 165 Pup 5.7 15.0' 07h52m10.0s -38°31'48" 4000 ly 18:37 19:00 19:25 19 171 28 obvious Open NGC 2547 Collinder 177 Vel 5.0 25.0' 08h10m09.0s -49°12'54" 1500 ly 18:36 19:01 19:56 20 187 28 obvious PNe NGC 2818 He 2-23 Pyx 11.9 36" 09h16m01.7s -36°37'39" 6000 ly 18:38 19:01 20:45 20 170 39 easy Open NGC 2516 Collinder 172 Car 3.3 30.0' 07h58m04.0s -60°45'12" 1300 ly 18:35 19:02 19:55 24 200 30 obvious Open Collinder 205 Markarian 18 Vel 8.4 5.0' 09h00m32.0s -48°59'00" -

108 Afocal Procedure, 105 Age of Globular Clusters, 25, 28–29 O

Index Index Achromats, 70, 73, 79 Apochromats (APO), 70, Averted vision Adhafera, 44 73, 79 technique, 96, 98, Adobe Photoshop Aquarius, 43, 99 112 (software), 108 Aquila, 10, 36, 45, 65 Afocal procedure, 105 Arches cluster, 23 B1620-26, 37 Age Archinal, Brent, 63, 64, Barkhatova (Bar) of globular clusters, 89, 195 catalogue, 196 25, 28–29 Arcturus, 43 Barlow lens, 78–79, 110 of open clusters, Aricebo radio telescope, Barnard’s Galaxy, 49 15–16 33 Basel (Bas) catalogue, 196 of star complexes, 41 Aries, 45 Bayer classification of stellar associations, Arp 2, 51 system, 93 39, 41–42 Arp catalogue, 197 Be16, 63 of the universe, 28 Arp-Madore (AM)-1, 33 Beehive Cluster, 13, 60, Aldebaran, 43 Arp-Madore (AM)-2, 148 Alessi, 22, 61 48, 65 Bergeron 1, 22 Alessi catalogue, 196 Arp-Madore (AM) Bergeron, J., 22 Algenubi, 44 catalogue, 197 Berkeley 11, 124f, 125 Algieba, 44 Asterisms, 43–45, Berkeley 17, 15 Algol (Demon Star), 65, 94 Berkeley 19, 130 21 Astronomy (magazine), Berkeley 29, 18 Alnilam, 5–6 89 Berkeley 42, 171–173 Alnitak, 5–6 Astronomy Now Berkeley (Be) catalogue, Alpha Centauri, 25 (magazine), 89 196 Alpha Orionis, 93 Astrophotography, 94, Beta Pictoris, 42 Alpha Persei, 40 101, 102–103 Beta Piscium, 44 Altair, 44 Astroplanner (software), Betelgeuse, 93 Alterf, 44 90 Big Bang, 5, 29 Altitude-Azimuth Astro-Snap (software), Big Dipper, 19, 43 (Alt-Az) mount, 107 Binary millisecond 75–76 AstroStack (software), pulsars, 30 Andromeda Galaxy, 36, 108 Binary stars, 8, 52 39, 41, 48, 52, 61 AstroVideo (software), in globular clusters, ANR 1947 -

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

![Arxiv:1803.10763V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 28 Mar 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1474/arxiv-1803-10763v1-astro-ph-ga-28-mar-2018-2151474.webp)

Arxiv:1803.10763V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 28 Mar 2018

Draft version October 10, 2018 Typeset using LATEX default style in AASTeX61 TRACERS OF STELLAR MASS-LOSS - II. MID-IR COLORS AND SURFACE BRIGHTNESS FLUCTUATIONS Rosa A. Gonzalez-L´ opezlira´ 1 1Instituto de Radioastronomia y Astrofisica, UNAM, Campus Morelia, Michoacan, Mexico, C.P. 58089 (Received 2017 October 20; Revised 2018 February 20; Accepted 2018 February 21) Submitted to ApJ ABSTRACT I present integrated colors and surface brightness fluctuation magnitudes in the mid-IR, derived from stellar popula- tion synthesis models that include the effects of the dusty envelopes around thermally pulsing asymptotic giant branch (TP-AGB) stars. The models are based on the Bruzual & Charlot CB∗ isochrones; they are single-burst, range in age from a few Myr to 14 Gyr, and comprise metallicities between Z = 0.0001 and Z = 0.04. I compare these models to mid-IR data of AGB stars and star clusters in the Magellanic Clouds, and study the effects of varying self-consistently the mass-loss rate, the stellar parameters, and the output spectra of the stars plus their dusty envelopes. I find that models with a higher than fiducial mass-loss rate are needed to fit the mid-IR colors of \extreme" single AGB stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Surface brightness fluctuation magnitudes are quite sensitive to metallicity for 4.5 µm and longer wavelengths at all stellar population ages, and powerful diagnostics of mass-loss rate in the TP-AGB for intermediater-age populations, between 100 Myr and 2-3 Gyr. Keywords: stars: AGB and post{AGB | stars: mass-loss | Magellanic Clouds | infrared: stars | stars: evolution | galaxies: stellar content arXiv:1803.10763v1 [astro-ph.GA] 28 Mar 2018 Corresponding author: Rosa A. -

Multiple Stellar Populations in Magellanic Cloud Clusters. VI. A

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 000–000 (0000) Printed 1 March 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) Multiple stellar populations in Magellanic Cloud clusters.VI. A survey of multiple sequences and Be stars in young clusters A. P.Milone1,2, A. F. Marino2, M. Di Criscienzo3, F. D’Antona3, L.R.Bedin4, G. Da Costa2, G. Piotto1,4, M. Tailo5, A. Dotter6, R. Angeloni7,8, J.Anderson9, H. Jerjen2, C. Li10, A. Dupree6, V.Granata1,4, E. P.Lagioia1,11,12, A. D. Mackey2, D. Nardiello1,4, E. Vesperini13 1Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “Galileo Galilei”, Univ. di Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 3, Padova, IT-35122 2Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia 3Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica - Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, Via Frascati 33, I-00040 Monteporzio Catone, Roma, Italy 4Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica - Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, Padova, IT-35122 5 Dipartimento di Fisica, Universita’ degli Studi di Cagliari, SP Monserrato-Sestu km 0.7, 09042 Monserrato, Italy 6 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA, USA 7 Departamento de Fisica y Astronomia, Universidad de La Serena, Av. Juan Cisternas 1200 N, La Serena, Chile 8 Instituto de Investigacion Multidisciplinar en Ciencia y Tecnologia, Universidad de La Serena, Raul Bitran 1305, La Serena, Chile 9Space Telescope Science Institute, 3800 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 10 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia 11Instituto de Astrof`ısica de Canarias, E-38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain 12Department of Astrophysics, University of La Laguna, E-38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain 13Department of Astronomy, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA Accepted 2018 February 27. -

Turn Left at Orion

This page intentionally left blank Turn Left at Orion A hundred night sky objects to see in a small telescope — and how to find them Third edition Guy Consolmagno Vatican Observatory, Tucson Arizona and Vatican City State Dan M. Davis State University ofNew York at Stony Brook illustrations by Karen Kotash Sepp, Anne Drogin, and Mary Lynn Skirvin CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521781909 © Cambridge University Press 1989, 1995, 2000 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published in print format 2000 ISBN-13 978-0-511-33717-8 eBook (EBL) ISBN-10 0-511-33717-5 eBook (EBL) ISBN-13 978-0-521-78190-9 hardback ISBN-10 0-521-78190-6 hardback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. How Do You Get to Albireo? .............................4 How to Use This Book ....................................... 6 Contents The Moon ......................................................... 12 Lunar Eclipses Worldwide, 2004–2020 ........................... 23 The Planets ......................................................26 Approximate Positions of the Planets, 2004–2019.......... 28 When to See Mercury in the Evening Sky, 2004–2019 ... -

INFRARED SURFACE BRIGHTNESS FLUCTUATIONS of MAGELLANIC STAR CLUSTERS1 Rosa A

The Astrophysical Journal, 611:270–293, 2004 August 10 A # 2004. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. INFRARED SURFACE BRIGHTNESS FLUCTUATIONS OF MAGELLANIC STAR CLUSTERS1 Rosa A. Gonza´lez Centro de Radioastronomı´a y Astrofı´sica, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Me´xico, Campus Morelia, Michoaca´n CP 58190, Mexico; [email protected] Michael C. Liu Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822; [email protected] and Gustavo Bruzual A. Centro de Investigaciones de Astronomı´a, Apartado Postal 264, Me´rida 5101-A, Venezuela; [email protected] Received 2003 November 27; accepted 2004 April 16 ABSTRACT We present surface brightness fluctuations (SBFs) in the near-IR for 191 Magellanic star clusters available in the Second Incremental and All Sky Data releases of the Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS) and compare them with SBFs of Fornax Cluster galaxies and with predictions from stellar population models as well. We also construct color-magnitude diagrams (CMDs) for these clusters using the 2MASS Point Source Catalog (PSC). Our goals are twofold. The first is to provide an empirical calibration of near-IR SBFs, given that existing stellar population synthesis models are particularly discrepant in the near-IR. Second, whereas most previous SBF studies have focused on old, metal-rich populations, this is the first application to a system with such a wide range of ages (106 to more than 1010 yr, i.e., 4 orders of magnitude), at the same time that the clusters have a very narrow range of metallicities (Z 0:0006 0:01, i.e., 1 order of magnitude only). -

South Best Winter

South Best Winter (103 objects) Object Type Mag Size Information NGC 1187 GX 10.6 4.2'x3.2' R03:02:37.6 D-22:52:02 Eridanus Type: SBc, SB: 13.3, mag_b: 11.3 NGC 1232 GX 9.8 7.4'x6.5' R03:09:45.3 D-20:34:45 Eridanus Type: SBc, SB: 13.9, mag_b: 10.5 NGC 1291 GX 8.5 11.0'x9.5' R03:17:18.3 D-41:06:26 Eridanus Type: SB0-a, SB: 13.4, mag_b: 9.4 NGC 1300 GX 10.3 6.2'x4.1' R03:19:40.7 D-19:24:41 Eridanus Type: SBbc, SB: 13.7, mag_b: 11.1 NGC 1421 GX 11.4 3.4'x0.8' R03:42:29.4 D-13:29:16 Eridanus Type: SBbc, SB: 12.3, mag_b: 12.2 32 Eri * G5 5.00 R03:54:17.5 D-02:57:16.9 Eridanus SAO 130806 NGC 1515 GX 11.3 5.4'x1.3' R04:04:02.1 D-54:06:00 Dorado Type: SBbc, SB: 13.3, mag_b: 12.1 NGC 1533 GX 10.7 2.8'x2.3' R04:09:51.9 D-56:07:04 Dorado Type: SB0, SB: 12.6, mag_b: 11.7 NGC 1532 GX 9.8 11.6'x3.4' R04:12:03.8 D-32:52:23 Eridanus Type: SBb, SB: 13.6, mag_b: 10.6 NGC 1535 PN 9.6 0.9' R04:14:15.8 D-12:44:20 Eridanus Type: PN, mag_b: 9.6 39 Eri * K0 5.10 R04:14:23.7 D-10:15:22.7 Eridanus SAO 149478 NGC 1546 GX 11.0 3.2'x1.9' R04:14:36.7 D-56:03:37 Dorado Type: S0-a, SB: 12.8, mag_b: 11.9 Keid * G5 4.50 R04:15:16.3 D-07:39:09.9 Eridanus 2 Eri Vulcan SAO 131063 NGC 1549 GX 9.6 4.9'x4.1' R04:15:45.0 D-55:35:29 Dorado Type: E0, SB: 12.9, mag_b: 10.6 NGC 1553 GX 9.0 4.5'x2.8' R04:16:10.6 D-55:46:46 Dorado Type: S0, SB: 11.6, mag_b: 10.0 NGC 1566 GX 9.4 8.2'x6.5' R04:20:00.5 D-54:56:14 Dorado Type: SBbc, SB: 13.6, mag_b: 10.2 NGC 1617 GX 10.5 4.3'x2.1' R04:31:39.5 D-54:36:07 Dorado Type: SBa, SB: 12.7, mag_b: 11.4 55 Eri * F5 6.70 R04:43:35.1 D-08:47:45.8