What America Reads: Myth Making in Popular Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

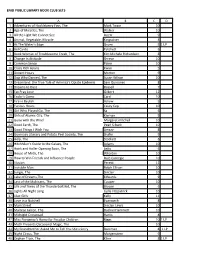

Web Book Club Sets

ENID PUBLIC LIBRARY BOOK CLUB SETS A B C D 1 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Mark Twain 10 2 Age of Miracles, The Walker 10 3 All the Light We Cannot See Doerr 9 4 Animal, Vegetable, Miracle Kingsolver 4 5 At The Water's Edge Gruen 5 1 LP 6 Bel Canto Patchett 6 7 Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, The Kim Michele Richardson 8 8 Change in Attitude Shreve 10 9 Common Sense Paine 10 10 Crazy Rich Asians Kwan 5 11 Distant Hours Morton 9 12 Dog Who Danced, The Susan Wilson 10 13 Dreamland: the True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic Sam Quinones 8 14 Dreams to Dust Russell 7 15 Eat Pray Love Gilbert 12 16 Ender's Game Card 10 17 Fire in Beulah Askew 5 18 Furious Hours Casey Cep 10 19 Girl Who Played Go, The Sa 6 20 Girls of Atomic City, The Kiernan 9 21 Gone with the Wind Margaret mitchell 10 22 Good Earth, The Pearl S Buck 10 23 Good Things I Wish You Amsay 8 24 Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society, The Shafer 9 25 Help, The Stockett 6 26 Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, The Adams 10 27 Honk and Holler Opening Soon, The Letts 6 28 House of Mirth, The Wharton 10 29 How to Win Friends and Influence People Dale Carnegie 10 30 Illusion Peretti 12 31 Invisible Man Ralph Ellison 10 32 Jungle, The Sinclair 10 33 Lake of Dreams,The Edwards 9 34 Last of the Mohicans, The Cooper 10 35 Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, The Bryson 6 36 Lights All Night Long Lydia Fitzpatrick 10 37 Lilac Girls Kelly 11 38 Love in a Nutshell Evanovich 8 39 Main Street Sinclair Lewis 10 40 Maltese Falcon, The Dashiel Hammett 10 41 Midnight Crossroad Harris 8 -

"Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History Annjeanette C. Rose College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Annjeanette C., "Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625795. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-g6vx-t170 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REMEMBERING TO FORGET: GONE WITH THE WIND. ROOTS. AND CONSUMER HISTORY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Anjeanette C. Rose 1993 for C. 111 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CJ&52L- Author Approved, April 1993 L _ / v V T < Kirk Savage Ri^ert Susan Donaldson TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................. v ABSTRACT.........................................................................................................................vi -

Rhett Butler and the Law of War at Sea

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2000 Into the Wind: Rhett utleB r and the Law of War at Sea John Paul Jones University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Admiralty Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation John Paul Jones, Into the Wind: Rhett uB tler and the Law of War at Sea, 31 J. Mar. L. & Com. 633 (2000) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. journal of Maritime Law and Commerce, Vol. 31, No. 4, October, 2000 Into the Wind: Rhett Butler and the Law of War at Sea JOHN PAUL JONES* I INTRODUCTION When Margaret Mitchell wrote Gone With the Wind, her epic novel of the American Civil War, she introduced to fiction the unforgettable character Rhett Butler. What makes Butler unforgettable for readers is his unsettling moral ambiguity, which Clark Gable brilliantly communicated from the screen in the movie version of Mitchell's work. Her clever choice of Butler's wartime calling aggravates the unease with which readers contemplate Butler, for the author made him a blockade runner. As hard as Butler is to figure out-a true scoundrel or simply a great pretender?-so is it hard to morally or historically pigeonhole the blockade running captains of the Confederacy. -

Gone with the Wind Part 1

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

Banned & Challenged Classics

26. Gone with the Wind, 26. Gone with the Wind, by Margaret Mitchell by Margaret Mitchell 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright Banned & Banned & 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Challenged Challenged by Ken Kesey by Ken Kesey 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, Classics Classics by Kurt Vonnegut by Kurt Vonnegut 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, by Ernest Hemingway by Ernest Hemingway 33. The Call of the Wild, 33. The Call of the Wild, The titles below represent banned or The titles below represent banned or by Jack London by Jack London challenged books on the Radcliffe challenged books on the Radcliffe 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of by James Baldwin by James Baldwin the 20th Century list: the 20th Century list: 38. All the King's Men, 38. All the King's Men, 1. The Great Gatsby, 1. The Great Gatsby, by Robert Penn Warren by Robert Penn Warren by F. Scott Fitzgerald by F. Scott Fitzgerald 40. The Lord of the Rings, 40. The Lord of the Rings, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.D. Salinger by J.D. Salinger 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 3. The Grapes of Wrath, 3. -

Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.; * Warner Bros

United States Court of Appeals FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT ________________ No. 10-1743 ________________ Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.; * Warner Bros. Consumer Products, * Inc.; Turner Entertainment Co., * * Appellees, * * v. * Appeal from the United States * District Court for the X One X Productions, doing * Eastern District of Missouri. business as X One X Movie * Archives, Inc.; A.V.E.L.A., Inc., * doing business as Art & Vintage * Entertainment Licensing Agency; * Art-Nostalgia.com, Inc.; Leo * Valencia, * * Appellants. * _______________ Submitted: February 24, 2011 Filed: July 5, 2011 ________________ Before GRUENDER, BENTON, and SHEPHERD, Circuit Judges. ________________ GRUENDER, Circuit Judge. A.V.E.L.A., Inc., X One X Productions, and Art-Nostalgia.com, Inc. (collectively, “AVELA”) appeal a permanent injunction prohibiting them from licensing certain images extracted from publicity materials for the films Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, as well as several animated short films featuring the cat- and-mouse duo “Tom & Jerry.” The district court issued the permanent injunction after granting summary judgment in favor of Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc., Warner Bros. Consumer Products, Inc., and Turner Entertainment Co. (collectively, “Warner Bros.”) on their claim that the extracted images infringe copyrights for the films. For the reasons discussed below, we affirm in part, reverse in part, and remand for appropriate modification of the permanent injunction. I. BACKGROUND Warner Bros. asserts ownership of registered copyrights to the 1939 Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer (“MGM”) films The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind. Before the films were completed and copyrighted, publicity materials featuring images of the actors in costume posed on the film sets were distributed to theaters and published in newspapers and magazines. -

Reaching Across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Technology Faculty Publications Jan. 2015) 2013 Reaching Across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship Jearl Nix Chara Haeussler Bohan Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/msit_facpub Part of the Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons, Instructional Media Design Commons, Junior High, Intermediate, Middle School Education and Teaching Commons, and the Secondary Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Nix, J. & Bohan, C. H. (2013). Reaching across the color line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an uncommon friendship. Social Education, 77(3), 127–131. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Jan. 2015) at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social Education 77(3), pp 127–131 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies Reaching across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship Jearl Nix and Chara Haeussler Bohan In 1940, Atlanta was a bustling town. It was still dazzling from the glow of the previous In Atlanta, the color line was clearly year’s star-studded premiere of Gone with the Wind. The city purchased more and drawn between black and white citizens. -

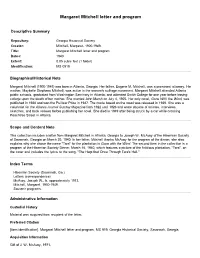

Margaret Mitchell Letter and Program

Margaret Mitchell letter and program Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Creator: Mitchell, Margaret, 1900-1949. Title: Margaret Mitchell letter and program Dates: 1940 Extent: 0.05 cubic feet (1 folder) Identification: MS 0919 Biographical/Historical Note Margaret Mitchell (1900-1949) was born in Atlanta, Georgia. Her father, Eugene M. Mitchell, was a prominent attorney. Her mother, Maybelle Stephens Mitchell, was active in the women's suffrage movement. Margaret Mitchell attended Atlanta public schools, graduated from Washington Seminary in Atlanta, and attended Smith College for one year before leaving college upon the death of her mother. She married John Marsh on July 4, 1925. Her only novel, Gone With the Wind, was published in 1936 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1937. The movie based on the novel was released in 1939. She was a columnist for the Atlanta Journal Sunday Magazine from 1922 until 1926 and wrote dozens of articles, interviews, sketches, and book reviews before publishing her novel. She died in 1949 after being struck by a car while crossing Peachtree Street in Atlanta. Scope and Content Note This collection includes a letter from Margaret Mitchell in Atlanta, Georgia to Joseph W. McAvoy of the Hibernian Society of Savannah, Georgia on March 20, 1940. In her letter, Mitchell thanks McAvoy for the program of the dinner; she also explains why she chose the name "Tara" for the plantation in Gone with the Wind. The second item in the collection is a program of the Hibernian Society Dinner, March 16, 1940, which features a picture of the fictitious plantation, "Tara", on the cover and includes the lyrics to the song, "The Harp that Once Through Tara's Hall." Index Terms Hibernian Society (Savannah, Ga.) Letters (correspondence) McAvoy, Joseph W., b. -

“Best Books of the Century”

19. The Hobbit 40. The Little Prince “BEST BOOKS J.R.R. Tolkien Antoine de Saint-Exupery OF THE CENTURY” 20. Number the Stars Lois Lowry 41. The World According to Garp 21. Slaughterhouse-Five John Irving Kurt Vonnegut 42. A Farewell to Arms 22. Ulysses Ernest Hemingway James Joyce 43. The Fountainhead 23. For Whom the Bell Tolls Ayn Rand Ernest Hemingway 44. Hatchet 24. Harold and the Purple Gary Paulsen Crayon Crockett Johnson 45. The Lion, the Witch & the Wardrobe 25. Invisible Man C.S. Lewis Ralph Ellison 46. Lolita 26. The Lord of the Rings Vladimir Nabokov Northport-East Northport Public Library Trilogy J.R.R. Tolkien 47. Of Human Bondage 1999 W. Somerset Maugham Main Reading Room 27. Anne of Green Gables L.M. Montgomery 48. The Sound and the Fury In the spring of 1999, the Library Trustees commissioned William Faulkner Northport sculptor George W. Hart to create The Millennium 28. Beloved Bookball. This complex spherical arrangement of 60 Toni Morrison 49. Where the Red Fern Grows interlocking books is suspended from the ceiling of the Wilson Rawls 29. Where the Sidewalk Main Reading Room of the Northport Library. Each book Ends 50. An American Tragedy is engraved with the title and author of one of the “Best Shel Silverstein Theodore Dreiser Books of the Century” as selected by community members. This unique and beautiful work of art was funded, in 30. Charlie and the 51. Brave New World Chocolate Factory Aldous Huxley part, through generous donations from community residents Roald Dahl whose names are engraved on a plaque in Northport’s 52. -

SUMMER READING ASSIGNMENT English 11 VITAL INFORMATION: 1. Choose One Novel to Read from This List Below: the Sound And

SUMMER READING ASSIGNMENT English 11 VITAL INFORMATION: 1. Choose one novel to read from this list below: The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner My Antonia by Willa Cather House of the Seven Gables by Nathaniel Hawthorne The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath Gone With the Wind by Margaret Mitchell The Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison The Awakening by Kate Chopin The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain Coming Back Stronger: Unleashing the Power of Adversity by Drew Brees A Farewell To Arms by Ernest Hemingway This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald 2. Complete Two of the following five options from the assignment packet: Assignment 1: Reading Vocabulary Assignment 2: Plot Assignment 3: Connections (Do not use the same “connection” for all answers. For example, if you use a “life experience” for two connections, choose a book or movie for the third.) Assignment 4: Book Review 3. Assignments are due by the first day of school. 4. The summer reading assignment will be counted as a daily and quiz grade for Q1. 5. Staple all your entries for the book together before you turn them in. HELPFUL HINTS: An easy way to prepare for these assessments is to answer the questions as you read or annotate your book with sticky notes or highlighters. If you do this, you will not have to go searching for the information you read a few weeks prior to starting the project. To earn full credit for each answer, you must use grammatically correct and structurally sound sentences, as well as detailed answers and specific examples from the books. -

Why Atlanta for the Permanent Things?

Atlanta and The Permanent Things William F. Campbell, Secretary, The Philadelphia Society Part One: Gone With the Wind The Regional Meetings of The Philadelphia Society are linked to particular places. The themes of the meeting are part of the significance of the location in which we are meeting. The purpose of these notes is to make our members and guests aware of the surroundings of the meeting. This year we are blessed with the city of Atlanta, the state of Georgia, and in particular The Georgian Terrace Hotel. Our hotel is filled with significant history. An overall history of the hotel is found online: http://www.thegeorgianterrace.com/explore-hotel/ Margaret Mitchell’s first presentation of the draft of her book was given to a publisher in the Georgian Terrace in 1935. Margaret Mitchell’s house and library is close to the hotel. It is about a half-mile walk (20 minutes) from the hotel. http://www.margaretmitchellhouse.com/ A good PBS show on “American Masters” provides an interesting view of Margaret Mitchell, “American Rebel”; it can be found on your Roku or other streaming devices: http://www.wgbh.org/programs/American-Masters-56/episodes/Margaret-Mitchell- American-Rebel-36037 The most important day in hotel history was the premiere showing of Gone with the Wind in 1939. Hollywood stars such as Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, and Olivia de Haviland stayed in the hotel. Although Vivien Leigh and her lover, Lawrence Olivier, stayed elsewhere they joined the rest for the pre-Premiere party at the hotel. Our meeting will be deliberating whether the Permanent Things—Truth, Beauty, and Virtue—are in fact, permanent, or have they gone with the wind? In the movie version of Gone with the Wind, the opening title card read: “There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South.. -

Dog Soldiers 5.Indd

www.elboomeran.com Dog Soldiers Robert Stone Prólogo de Rodrigo Fresán Traducción de Mariano Antolín e Inga Pellisa Miradas Título de la edición original: Dog Soldiers Primera edición en Libros del Silencio: octubre de 2010 © Robert Stone, 1973, 1985 © de la traducción, Mariano Antolín Rato e Inga Pellisa, 2010 © del prólogo, Rodrigo Fresán, 2010 © de la presente edición, Editorial Libros del Silencio, S. L. [2010] Provença, 225, entresuelo 3.ª 08008 Barcelona +34 93 487 96 37 +34 93 487 92 07 www.librosdelsilencio.com Diseño colección: Nora Grosse, Enric Jardí Diseño cubierta: Opalworks ISBN: 978-84-937856-5-9 Depósito legal: B-33.746-2010 Impreso por Romanyà Valls Impreso en España - Printed in Spain Todos los derechos reservados. Quedan rigurosamente prohibidas, sin la autorización es- crita de los titulares del copyright, bajo las sanciones establecidas en las leyes, la reproduc- ción parcial o total de esta obra por cualquier medio o procedimiento, comprendidos la reprografía y el tratamiento informático, y la distribución de ejemplares mediante alquiler o préstamo públicos. Apuntes para una teoría de Vietnam como virus y droga Rodrigo Fresán uno. «Saigon... Shit, I’m still only in Saigon. Everytime, I think I’m gonna wake up back in the jungle»1 es lo primero que oímos —luego de un rumor de helicópteros y un estallido de napalm— en una película magistral llamada Apocalypse Now (1979). Nos lo dice una voz en off —seguimos en Saigón, la jungla crece al otro lado de los párpados cerrados— que es la voz de quien escribió esas palabras para el film de Francis Ford Coppola: la del perio- dista bélico Michael Herr, autor de Despachos (1977), seguramen- te el mejor libro sobre la guerra de Vietnam e incuestionable obra maestra del Nuevo Periodismo.