Edited by Walter Bock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Blas Checklist-2019

San Blas & Durango Highway Otus asio Tours COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME 3/6 3/7 3/8 3/9 3/10 3/11 3/12 3/13 3/14 3/15 3/16 ANATIDAE 1. Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis 11 2. Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors 100 40 6 5 3. Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera 2 2 23 4. Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata 100 7 15 4 1 21 5. Gadwall Mareca strepera 6 3 6. American Wigeon Mareca americana 3 7. Northern Pintail Anas acuta 2 8. Green-winged Teal Anas crecca 2 9. Redhead Aythya americana 8 10. Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis 30 11. Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 7 7 16 CRACIDAE 12. Rufous-bellied Chachalaca Ortalis wagleri 3 4 2 15 9 4 13. Crested Guan Penelope purpurescens 2 3 2 ODONTOPHORIDAE 14. Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 3 1 1 15. Singing Quail Dactylortyx thoracicus H PODICIPEDIDAE 16. Least Grebe Tachybaptus dominicus 3 2 17. Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps 2 18. Eared Grebe Podiceps nigricollis 1 4 19. Clark’s Grebe Aechmophorus clarkii 8 COLUMBIDAE 20. Rock Pigeon (I) Columba livia 10 3 5 2 5 10 5 6 1 San Blas & Durango Highway Otus asio Tours 21. Red-billed Pigeon Patagioenis flavirostris 4 12 6 4 8 22. Band-tailed Pigeon Patagioenas fasciata 1 23. Eurasian Collared-Dove Streptopelia decaocto 10 1 2 2 2 2 3 3 2 24. Inca Dove Columbina inca 2 3 2 3 6 1 1 25. Common Ground-Dove Columbina passerina 25 5 26. Ruddy Ground-Dove Columbina talpacoti 20 15 20 1 15 4 20 27. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Biography (Modified, After Festetics 1983)

Konrad Lorenz’s Biography (modified, after Festetics 1983) 1903: Konrad Zacharias Lorenz (KL) was born in Altenberg /Austria on Nov. 7 as the last of three children of Emma Lorenz and Dr. Adolf Lorenz, professor for orthopedics at the Medical branch of the University of Vienna. In the same year the representative and spacious Altenberg family home was finished. 1907: KL starts keeping animals, such as spotted newts in aquaria, raises some ducklings and is not pleased by his first experiences with a dachshound. Niko Tinbergen, his lifelong colleague and friend, is born on April 15 in Den Haag, The Netherlands. 1909: KL enters elementary school and engages in systematic studies in crustaceans. 1910: Oskar Heinroth, biologist and founder of "Vergleichende Verhaltensforschung" (comparative ethology) from Berlin and fatherlike scientific mentor of the young KL publishes his classical paper on the ethology of ducks. 1915: KL enters highschool (Schottengymnasium Wien), keeps and breeds songbirds. 1918: Wallace Craig publishes the comparative ethology of Columbidae (pigeons), a classics of late US biologist Charles O. Whitman, who was like O. Heinroth, a founding father of comparative ethology. 1921: KL excels in his final exams. Together with friend Bernhard Hellmann, he observes and experiments with aggression in a cichlid (Herichthys cyanoguttatum). This was the base for KL's psychohydraulic model of motivation. 1922: Father Adolf sends KL to New York to take 2 semesters of medicine courses at the ColumbiaUniversity, but mainly to interrupt the relationship of KL with longterm girlfriend Gretl Gebhart, his later wife. This paternal attempt to influence the mate choice of KL failed. -

Konrad Lorenz, NL Nobel Laureate in Physiology Or Medicine-1973

Glossary on Kalinga Prize Laureates UNESCO – Kalinga Prize Winner – 1974 Konrad Lorenz, NL Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine-1973 Great Zoologist and Ethologist [Birth : 7th November 1903 in Vienna, Austria Death : 27th February 1989, Vienna] Truth in Science can be defined as the working hypothesis best suited to open the way to the next better one. …Konrad Lonenz It is a good morning exercise for a research scientist to discard a Pet hypothesis every day before breakfast. It keeps him young. …Konrad Lonenz 1 Glossary on Kalinga Prize Laureates Konrad Lorenz Biography Ethology – Imprinting Konrad Lorenz (Konard Zacharisa Lorenz) was born on November 7, 1903 in Vienna, Austria. As a little boy, he loved animals and had a collection that include fish, dogs, monkeys, insects, ducks, and geese. His interest in animal behaviour was intense.When he was 10 years old, Lorenz became aware of the existence of the Theory of Evolution through reading a book by Wilhelm Bölsche in which he was fascinated by a picture of an Archaeopteryx. Evolution gave him insight-his father had explained that the word “insect” was derived from the notches, the “incisions” between the segments-if reptiles could become birds, annelid worms could develop into insects. As he grew towards adulthood he wanted to become a paleontologist, however he reluctantly followed his father’s wishes, and studied medicine at the University of Vienna and at Columbia University. He later regarded this compliance to have been in his own best interests as one of his teachers of anatomy, Ferdinand Hochstetter, proved to be a brilliant comparative anatomist and embryologist and a dedicated teacher of the comparative method. -

Gear for a Big Year

APPENDIX 1 GEAR FOR A BIG YEAR 40-liter REI Vagabond Tour 40 Two passports Travel Pack Wallet Tumi luggage tag Two notebooks Leica 10x42 Ultravid HD-Plus Two Sharpie pens binoculars Oakley sunglasses Leica 65 mm Televid spotting scope with tripod Fossil watch Leica V-Lux camera Asics GEL-Enduro 7 trail running shoes GoPro Hero3 video camera with selfie stick Four Mountain Hardwear Wicked Lite short-sleeved T-shirts 11” MacBook Air laptop Columbia Sportswear rain shell iPhone 6 (and iPhone 4) with an international phone plan Marmot down jacket iPod nano and headphones Two pairs of ExOfficio field pants SureFire Fury LED flashlight Three pairs of ExOfficio Give- with rechargeable batteries N-Go boxer underwear Green laser pointer Two long-sleeved ExOfficio BugsAway insect-repelling Yalumi LED headlamp shirts with sun protection Sea to Summit silk sleeping bag Two pairs of SmartWool socks liner Two pairs of cotton Balega socks Set of adapter plugs for the world Birding Without Borders_F.indd 264 7/14/17 10:49 AM Gear for a Big Year • 265 Wildy Adventure anti-leech Antimalarial pills socks First-aid kit Two bandanas Assorted toiletries (comb, Plain black baseball cap lip balm, eye drops, toenail clippers, tweezers, toothbrush, REI Campware spoon toothpaste, floss, aspirin, Israeli water-purification tablets Imodium, sunscreen) Birding Without Borders_F.indd 265 7/14/17 10:49 AM APPENDIX 2 BIG YEAR SNAPSHOT New Unique per per % % Country Days Total New Unique Day Day New Unique Antarctica / Falklands 8 54 54 30 7 4 100% 56% Argentina 12 435 -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Notices

21262 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Notices acquisition were not included in the 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA Comment (1): We received one calculation for TDC, the TDC limit would not 22041–3803; (703) 358–2376. comment from the Western Energy have exceeded amongst other items. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Alliance, which requested that we Contact: Robert E. Mulderig, Deputy include European starling (Sturnus Assistant Secretary, Office of Public Housing What is the purpose of this notice? vulgaris) and house sparrow (Passer Investments, Office of Public and Indian Housing, Department of Housing and Urban The purpose of this notice is to domesticus) on the list of bird species Development, 451 Seventh Street SW, Room provide the public an updated list of not protected by the MBTA. 4130, Washington, DC 20410, telephone (202) ‘‘all nonnative, human-introduced bird Response: The draft list of nonnative, 402–4780. species to which the Migratory Bird human-introduced species was [FR Doc. 2020–08052 Filed 4–15–20; 8:45 am]‘ Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. 703 et seq.) does restricted to species belonging to biological families of migratory birds BILLING CODE 4210–67–P not apply,’’ as described in the MBTRA of 2004 (Division E, Title I, Sec. 143 of covered under any of the migratory bird the Consolidated Appropriations Act, treaties with Great Britain (for Canada), Mexico, Russia, or Japan. We excluded DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 2005; Pub. L. 108–447). The MBTRA states that ‘‘[a]s necessary, the Secretary species not occurring in biological Fish and Wildlife Service may update and publish the list of families included in the treaties from species exempted from protection of the the draft list. -

MXSB 21 FIN ITIN, Needs $

The Beaches & Mountains of Pacific Mexico With Naturalist Journeys & Caligo Ventures March 11 – 21, 2021 866.900.1146 800.426.7781 520.558.1146 [email protected] www.naturalistjourneys.com or find us on Facebook at Naturalist Journeys, LLC Naturalist Journeys, LLC | Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 | 866.900.1146 Fax 650.471.7667 naturalistjourneys.com | caligo.com [email protected] | [email protected] The Pacific Slope of Mexico offers a unique tropical birding Tour Highlights experience, far from the rainforests on the Caribbean side of • Watch for up to 40 Pacific Slope the country and biographically isolated by the Sierra Madre endemics, several of which are Occidental. The jungles here are relatively dry and open common feeder birds compared to the dense, dripping rainforest, and we even • Witness many Neotropical migrants, visit habitat known as ‘thorn scrub’, where you may feel like including up to 20 migrant warblers you are birding in a desert. Our gateway of Puerto Vallarta • See nearly 30 possible flycatchers—the makes travel easy. We are never more than a few hours from world’s largest bird family—and up to Vallarta’s services. 25 different raptors • Explore the private 200-acre Rancho Itinerary Primavera, with its productive feeders and miles of well-maintained trails Thurs., Mar. 11 Arrivals | El Tuito • Discover productive aquatic habitats Our tour begins and ends in Puerto Vallarta, making travel and enjoy a ‘panga’ ride to the isolated easy with many direct flights from the United States and coastal town of Yelapa and evening Canada. -

Appendix S1. List of the 719 Bird Species Distributed Within Neotropical Seasonally Dry Forests (NSDF) Considered in This Study

Appendix S1. List of the 719 bird species distributed within Neotropical seasonally dry forests (NSDF) considered in this study. Information about the number of occurrences records and bioclimatic variables set used for model, as well as the values of ROC- Partial test and IUCN category are provide directly for each species in the table. bio 01 bio 02 bio 03 bio 04 bio 05 bio 06 bio 07 bio 08 bio 09 bio 10 bio 11 bio 12 bio 13 bio 14 bio 15 bio 16 bio 17 bio 18 bio 19 Order Family Genera Species name English nameEnglish records (5km) IUCN IUCN category Associated NDF to ROC-Partial values Number Number of presence ACCIPITRIFORMES ACCIPITRIDAE Accipiter (Vieillot, 1816) Accipiter bicolor (Vieillot, 1807) Bicolored Hawk LC 1778 1.40 + 0.02 Accipiter chionogaster (Kaup, 1852) White-breasted Hawk NoData 11 p * Accipiter cooperii (Bonaparte, 1828) Cooper's Hawk LC x 192 1.39 ± 0.06 Accipiter gundlachi Lawrence, 1860 Gundlach's Hawk EN 138 1.14 ± 0.13 Accipiter striatus Vieillot, 1807 Sharp-shinned Hawk LC 1588 1.85 ± 0.05 Accipiter ventralis Sclater, PL, 1866 Plain-breasted Hawk LC 23 1.69 ± 0.00 Busarellus (Lesson, 1843) Busarellus nigricollis (Latham, 1790) Black-collared Hawk LC 1822 1.51 ± 0.03 Buteo (Lacepede, 1799) Buteo brachyurus Vieillot, 1816 Short-tailed Hawk LC 4546 1.48 ± 0.01 Buteo jamaicensis (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Red-tailed Hawk LC 551 1.36 ± 0.05 Buteo nitidus (Latham, 1790) Grey-lined Hawk LC 1516 1.42 ± 0.03 Buteogallus (Lesson, 1830) Buteogallus anthracinus (Deppe, 1830) Common Black Hawk LC x 3224 1.52 ± 0.02 Buteogallus gundlachii (Cabanis, 1855) Cuban Black Hawk NT x 185 1.28 ± 0.10 Buteogallus meridionalis (Latham, 1790) Savanna Hawk LC x 2900 1.45 ± 0.02 Buteogallus urubitinga (Gmelin, 1788) Great Black Hawk LC 2927 1.38 ± 0.02 Chondrohierax (Lesson, 1843) Chondrohierax uncinatus (Temminck, 1822) Hook-billed Kite LC 1746 1.46 ± 0.03 Circus (Lacépède, 1799) Circus buffoni (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Long-winged Harrier LC 1270 1.61 ± 0.03 Elanus (Savigny, 1809) Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 29/09/2021. -

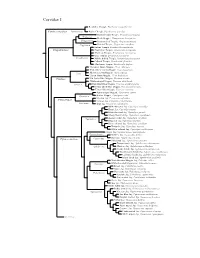

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

UK-First-Breeding-Register.Pdf

INTRODUCTION TO EDITION The original author and compiler of this record, Dave Coles has devoted a great deal of his time in creating a unique reference document which I am privileged to continue working with. By its very nature the document in a living project which will continue to grow and evolve and I can only hope and wish that I have the dedication as Dave has had in ensuring the continuity of the “First Breeding Register”. Initially all my additions and edits will be indicated in italics though this will not be used in the main body of the record (when a new record is added). Simon Matthews (2011) It is over eighty years since Emilius Hopkinson collated his RECORDS OF BIRDS BRED IN CAPTIVITY, which formed the starting point for my attempt at recording first breeding records for the UK. Since the first edition of my records was published in 1986, classification has changed several times and the present edition incorporates this up-dated classification as well as first breeding recorded since then. The research needed to produce the original volume took many years to complete and covered most avicultural literature. Since that time numerous people have kept me abreast of further breedings and pointing out those that have slipped the net. This has hopefully enabled the records to be kept up-to- date. To those I would express my thanks as indeed I do to all that have cast their eyes over the new list and passed comments, especially the ever helpful Reuben Girling who continues to pass on enquiries. -

Avian Survey Report

Spring/Summer 2010 Avian Survey Report Stony Creek Wind Farm Wyoming County, New York January 24, 2011 PREPARED FOR: Stony Creek Energy LLC 51 Monroe St. Suite 1604 Rockville, MD 20850 PREPARED BY: Lackawanna Executive Park 239 Main Street, Suite 301 Dickson City, PA 18519 www.shoenerenvironmental.com Stony Creek Wind Farm Avian Survey January 24, 2011 Table of Contents I. Summary and Background .................................................................................................1 Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Project Description ........................................................................................................1 Project Review Background ..........................................................................................2 II. Bald Eagle Survey .............................................................................................................3 Bald Eagle Breeding Status in New York ......................................................................3 Daily Movements of Bald Eagle in New York ...............................................................4 Bald Eagle Conservation Status in New York ................................................................4 Bald Eagle Survey Method ............................................................................................5 Analysis of Bald Eagle Survey Data ..............................................................................6 -

Federal Register/Vol. 70, No. 49/Tuesday, March 15, 2005/Notices

12710 Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 49 / Tuesday, March 15, 2005 / Notices values or resources that would be ADDRESSES: The complete file for this Commission; North Dakota Game and considered significant. notice is available for inspection, by Fish Department; Oklahoma Department Based upon this preliminary appointment (contact John L. Trapp, of Wildlife Conservation; Pennsylvania determination, we do not intend to (703) 358–1714), during normal Game Commission; Rhode Island prepare further NEPA documentation. business hours at U.S. Fish and Wildlife Division of Fish and Wildlife; South We will consider public comments in Service, 4501 North Fairfax Drive, Room Dakota Department of Game, Fish, and making the final determination on 4107, Arlington, Virginia. Parks; Vermont Department of Fish and whether to prepare such additional SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Wildlife; Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries; Wisconsin documentation. What Is the Authority for This Notice? This notice is provided pursuant to Department of Natural Resources; and section 10(c) of the Act. We will Migratory Bird Treaty Reform Act of Wyoming Game and Fish Department), evaluate the permit application, the 2004 (Division E, Title I, Sec. 143 of the 11 nonprofit organizations representing proposed Plan, and comments Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2005, bird conservation and science interests submitted thereon to determine whether Pub. L. 108–447). (American Bird Conservancy— submitted on behalf of 10 constituent the application meets the requirements What Is the Purpose of This Notice? organizations; Atlantic Flyway of section 10(a) of the Act. If the The purpose of this notice is to make requirements are met, we will issue a Council—representing 17 States, 7 the public aware of the final list of ‘‘all Provinces, Puerto Rico, and the U.S.