Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

CHAPTER E16 Atlas of Skin Manifestations of Internal Disease CHAPTER E16 Thomas J

CHAPTER e16 Atlas of Skin Manifestations of Internal Disease CHAPTER e16 Thomas J. Lawley Robert A. Swerlick In the practice of medicine, virtually every clinician encounters patients with skin disease. Physicians of all specialties face the daily task of determining the nature and clinical implication of dermatologic disease. In patients with skin eruptions and rashes, the physician must confront the question of whether the cutaneous Atlas of Skin Manifestations Internal Disease process is confined to the skin, representing a pure dermatologic event, or whether it is a manifestation of internal disease relating to the patient’s overall medical condition. Evaluation and accurate diagnosis of skin lesions are also critical given the marked rise in both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatologic conditions can be classified and categorized in many different ways, Figure e16-2 Acne rosacea with prominent facial erythema, telangiecta- and in this Atlas, a selected group of inflammatory skin eruptions sias, scattered papules, and small pustules. (Courtesy of Robert Swerlick, and neoplastic conditions are grouped in the following manner: MD; with permission.) (A) common skin diseases and lesions, (B) nonmelanoma skin cancer, (C) melanoma and pigmented lesions, (D) infectious dis- ease and the skin, (E) immunologically mediated skin disease, and (F) skin manifestations of internal disease. COMMON SKIN DISEASES AND LESIONS ( Figs. e16-1 to e16-19) In this section, several common inflamma- tory skin diseases and benign neoplastic and reactive lesions are presented. While most of these dermatoses usually present as a pre- dominantly dermatologic process, underlying systemic associations may be made in some settings. Atopic dermatitis is often present in patients with an atopic diathesis, including asthma and sinusitis. -

Ecthyma Gangrenosum of a Single Limb

Case Report Ecthyma gangrenosum of a single limb George M. Varghese, Pushpa Eapen1, Susanne Abraham1 Ecthyma gangrenosum is a skin manifestation of systemic sepsis commonly caused by Access this article online Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with neutropenia or underlying immune deficiency. Website: www.ijccm.org Although the usual outcome is poor, early recognition and appropriate systemic antibiotic DOI: 10.4103/0972-5229.84898 treatment can lead to successful outcome. We report a case of a previously healthy lady Quick Response Code: Abstract with no apparent immune deficiency or neutropenia who had ecthyma gangrenosum of left lower limb in which the arterial line was placed. Keywords: Ecthyma gangrenosum, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, single limb Introduction thachycardia. Three days later the patient was noted to Ecthyma gangrenosum is a known skin manifestation of have erythematous papules on the left lower limb. The 3 severe systemic infection commonly due to Pseudomonas white blood cell count was 16,500/mm (neutrophils aeruginosa. Most often it is seen in immunocompromised 84%, lymphocytes 12%, monocytes 3%, eosinophils 1%). or neutropenic patients who present with skin lesions Two sets of blood cultures were sent and the intra-arterial that begin as an erythematous nodule or hemorrhagic catheter was removed. The skin lesions were biopsied vesicle, which evolves into a necrotic ulcer with eschar. [1] and sent for histopathology and culture. Over the next The skin lesions are usually widespread over the body few days the skin lesions became blackish with necrotic and the case fatality rate is high. We report a case of areas (arrow) [Figure 1]. The blood, catheter tip, and skin ecthyma gangrenosum of left lower limb following lesion cultures yielded Pseudomonas aeruginosa sensitive arterial line in the left femoral artery in an individual to ceftazidime. -

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections Following Marine Injuries

CHAPTER 6 Skin and Soft Tissue Infections Following Marine Injuries V. Savini, R. Marrollo, R. Nigro, C. Fusella, P. Fazii Spirito Santo Hospital, Pescara, Italy 1. INTRODUCTION Bacterial diseases following aquatic injuries occur frequently worldwide and usually develop on the extremities of fishermen and vacationers, who are exposed to freshwater and saltwater.1,2 Though plenty of bacterial species have been isolated from marine lesions, superficial soft tissue and invasive systemic infections after aquatic injuries and exposures are related to a restricted number of microorganisms including, in alphabetical order, Aeromonas hydrophila, Chromobacterium violaceum, Edwardsiella tarda, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, Myco- bacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium marinum, Shewanella species, Streptococcus iniae, and Vibrio vulnificus.1,2 In particular, skin disorders represent the third most common cause of morbidity in returning travelers and are usually represented by bacterial infections.3–12 Bacterial skin and soft tissue infectious conditions in travelers often follow insect bites and can show a wide range of clinical pictures including impetigo, ecthyma, erysipelas, abscesses, necro- tizing cellulitis, myonecrosis.3–12 In general, even minor abrasions and lacerations sustained in marine waters should be considered potentially contaminated with marine bacteria.3–12 Despite variability of the causative agents and outcomes, the initial presentations of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) complicating marine injuries are similar to those occurring after terrestrial exposures and usually include erysipelas, impetigo, cellulitis, and necrotizing infections.3 Erysipelas is characterized by fiery red, tender, painful plaques showing well-demarcated edges, and, though Streptococcus pyogenes is the major agent of this pro- cess, E. rhusiopathiae infections typically cause erysipeloid displays.3 Impetigo is initially characterized by bullous lesions and is usually due to Staphylococcus aureus or S. -

Dermatology in the ER

DRUG ERUPTIONS and OTHER DISORDERS Lloyd J. Cleaver D.O. , F.A.O.C.D, F.A.A.D. Professor of Dermatology ATSU-Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine INTERNAL MEDICINE BOARD REVIEW COURSE I Disclosures No Relevant Financial Relationships DRUG ERUPTIONS Drug Reactions 3 things you need to know 1. Type of drug reaction 2. Statistics What drugs are most likely to cause that type of reaction? 3. Timing How long after the drug was started did the reaction begin? Clinical Pearls Drug eruptions are extremely common Tend to be generalized/symmetric Maculopapular/morbilliform are most common Best Intervention: Stop the Drug! Do not dose reduce Completely remove the exposure How to spot the culprit? Drug started within days to a week prior to rash Can be difficult and take time Tip: can generally exclude all drugs started after onset of rash Drug eruptions can continue for 1-2 weeks after stopping culprit drug LITT’s drug eruption database Drug Eruptions Skin is one of the most common targets for drug reactions Antibiotics and anticonvulsants are most common 1-5% of patients 2% of all drug eruptions are “serious” TEN, DRESS More common in adult females and boys < 3 y/o Not all drugs cause eruptions at same rate: Aminopenicillins: 1.2-8% of exposures TMP-SMX: 2.8-3.7% NSAIDs: 1 in 200 Lamotrigine: 10% Drug Eruptions Three basic rules 1. Stop any unnecessary medications 2. Ask about non-prescription medications Eye drops, suppositories, implants, injections, patches, vitamin and health supplements, friend’s medications -

Abdominal Distension, 284 Abdominal Mass, Hydatid Disease, 287

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-69761-3 - Case Studies in Pediatric Infectious Diseases Frank E. Berkowitz Index More information Index Abdominal distension, 284 perivenous, 240 Abdominal mass, hydatid disease, psoas 287 tuberculosis, 226 Abdominal pain, 12, 79, 112, 158, 169, 177, retropharyngeal, 100, 264, 318 257, 270, 273, 304, 308 tuberculosis, 226 acute HIV infection, 311 spinal epidural, 273 appendicitis, 253 spinal cat-scratch disease, 143 paraplegia, 262 hydatid disease, 287 subphrenic, 232 leptospirosis, 139 tubo-ovarian, 322 pelvic inflammatory disease, 319 Absidia, taxonomy, 347 peritonitis, 315 Acanthameba, taxonomy, 348 pneumonia, 248 Acetaminophen, 15, 54 pyelonephritis, 244 Acetylcholine, 129 typhus, 149 Acid-fast bacilli See Mycobacteria Abdominal tenderness, 257 Acidosis, diarrhea, 80 Abscess Acinetobacter, taxonomy, 342 appendix, 159, 255 Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, 146, brain, 43, 66, 255 193, 210, 242 meningitis, 108 reportable, 336 seizure, 195 Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, 153 Brodie’s, 282 taxonomy, 343 cerebellar, 327 infective endocarditis, 297 dental, 271 Actinomyces, 124, 127 epidural, 334 taxonomy, 344 eye, 314 Actinomyces israelii, 125 lateral pharyngeal, 264 Actinomyces odontolyticus, taxonomy, liver, 13, 174 344 amebic, 174 Actinomycosis, 125 lung, 249 Acute chest syndrome, sickle cell disease, 249, odontogenic See Abscess 324 dental Acyclovir, 42 pelvic, 306 Epstein–Barr virus, 39 peritonsillar, 100, 264 herpes simplex virus, 29 Lemierre syndrome, 332 varicella, 47 355 © Cambridge University -

Dermatological Indications of Disease - Part II This Patient on Dialysis Is Showing: A

“Cutaneous Manifestations of Disease” ACOI - Las Vegas FR Darrow, DO, MACOI Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine This 56 year old man has a history of headaches, jaw claudication and recent onset of blindness in his left eye. Sed rate is 110. He has: A. Ergot poisoning. B. Cholesterol emboli. C. Temporal arteritis. D. Scleroderma. E. Mucormycosis. Varicella associated. GCA complex = Cranial arteritis; Aortic arch syndrome; Fever/wasting syndrome (FUO); Polymyalgia rheumatica. This patient missed his vaccine due at age: A. 45 B. 50 C. 55 D. 60 E. 65 He must see a (an): A. neurologist. B. opthalmologist. C. cardiologist. D. gastroenterologist. E. surgeon. Medscape This 60 y/o male patient would most likely have which of the following as a pathogen? A. Pseudomonas B. Group B streptococcus* C. Listeria D. Pneumococcus E. Staphylococcus epidermidis This skin condition, erysipelas, may rarely lead to septicemia, thrombophlebitis, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis. Involves the lymphatics with scarring and chronic lymphedema. *more likely pyogenes/beta hemolytic Streptococcus This patient is susceptible to: A. psoriasis. B. rheumatic fever. C. vasculitis. D. Celiac disease E. membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Also susceptible to PSGN and scarlet fever and reactive arthritis. Culture if MRSA suspected. This patient has antithyroid antibodies. This is: • A. alopecia areata. • B. psoriasis. • C. tinea. • D. lichen planus. • E. syphilis. Search for Hashimoto’s or Addison’s or other B8, Q2, Q3, DRB1, DR3, DR4, DR8 diseases. This patient who works in the electronics industry presents with paresthesias, abdominal pain, fingernail changes, and the below findings. He may well have poisoning from : A. lead. B. -

Connubial Ecthyma Gangrenosum in a Healthy Couple: a Consort Counterpart of a “Kissing Ulcer”

Acta Dermatovenerologica 2015;24:11-12 Acta Dermatovenerol APA Alpina, Pannonica et Adriatica doi: 10.15570/actaapa.2015.4 Connubial ecthyma gangrenosum in a healthy couple: a consort counterpart of a “kissing ulcer” Miloš D. Pavlović1 ✉, Metka Adamič1 Abstract Ecthyma gangrenosum is a relatively rare cutaneous infection generally thought to be linked to sepsis or bacteremia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in severely ill or otherwise immunocompromised patients. Here we report on a healthy middle-aged couple with a typical ecthyma gangrenosum lesion on their thighs, obviously caused by spreading through intimate contact be- tween two skin surfaces: a sort of “consort kissing ulcer.” Although they declined to allow microbiological sampling, the lesions gradually but completely regressed with oral ciprofloxacin treatment, leaving atrophic scars. Keywords: case report, skin infection, ecthyma gangrenosum Received: 1 December 2014 | Returned for modification: 22 December 2014 | Accepted: 12 January 2015 Introduction Case report Ecthyma gangrenosum is a rare cutaneous infection, most com- A 49-year-old woman and her 53-year-old partner came to our der- monly caused by the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aer- matology center for an extremely painful red and ulcerated plaque uginosa (1, 2). It typically starts with an erythematous or purpuric on their thighs. The lesions appeared in both of them roughly si- macule and rapidly develops into a hemorrhagic bulla or pustule multaneously 2 to 3 weeks prior to presentation as a small reddish surrounded by a narrow pink to violaceous halo. Then it ruptures macule that evolved into a hemorrhagic bulla that ruptured and to become a round ulcer with a necrotic black or a gunmetal-gray transformed into an enlarging ulcer. -

Fever and Rash in the Non-HIV Immunocompromised Host

Anna Skiada University of Athens © by author ESCMID Online Lecture Library >20% of immunocompromised hosts will develop skin lesions, often with fever Multiple defects in host defense lead to different types of infection These lesions may reflect disseminated infection © by author Evaluation of the skin may provide the most ESCMIDrapid diagnosis Online Lecture Library 1. Presence of signs and symptoms other than the rash 2. Recognize the clinical settings: 1. Constructions near the hospital leads to suspicion of aspergillosis or mucormycosis 2. Cellulitis or hemorrhagic bullae in an acute febrile illness after© by exposure author to a salt water environment suggests Vibrio vulnificus ESCMID3. Fresh water Online contamination Lecture implicates Library Aeromonas. M.E. Grossman et al., Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host 3. Determine the host factors that predispose to certain infections: diabetic ketoacidosis, organ transplantation, acute leukemia, etc. 4. Timing of the skin lesions: in a patient who has had neutropenia for 3 days, bacterial infection is more© probableby author than fungal infection. ESCMID Online Lecture Library 5. In the neutropenic patient, the classic findings of swelling and fluctuance may be absent. There may be scant or no pus. 6. Determine the host factors that predispose to certain infections: diabetic ketoacidosis, organ transplantation, acute leukemia, etc. 7. Don’t exclude pathogens as “contaminants” 8. Inquire about geographic, nosocomial, occupational, or© behavioral by author exposures 9. History of travel and exposure to animals ESCMID Online Lecture Library 10. Skin biopsy should be performed for histology and culture to establish a definitive diagnosis. © by author ESCMID Online Lecture Library Bacterial infections . -

Ecthyma Gangrenosum Secondary to Methicillin-Sensitive Staphylococcus Aureus

International Journal of Women's Dermatology 2 (2016) 89–92 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Women's Dermatology Case Report Ecthyma gangrenosum secondary to methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus Jurate Ivanaviciene, MD, Lisa Chirch, MD, Jane M. Grant-Kels, MD ⁎, Philip E. Kerr, MD, Justin Finch, MD Departments of Medicine (Division of Infectious Diseases) and Dermatology, University of CT Health Center, Farmington, Connecticut article info abstract Article history: Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a well-described skin manifestation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicemia Received 21 March 2016 in immunocompromised patients. However, it can be seen in association with other bacteria, viruses, and Received in revised form 7 May 2016 fungi. We report a case of a 54-year-old African American female with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma Accepted 28 May 2016 and recent chemotherapy and neutropenia who developed EG-like lesions due to methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. We also review the literature to evaluate all reported cases of S aureus-associated EG and their clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. © 2016 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of Women's Dermatologic Society. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Introduction On admission, the patient’s blood pressure was 86/52 mmHg, heart rate 122 bpm, and temperature 103.7 °F. The patient was Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a well-described skin manifesta- alert, oriented, and not in any acute distress. Skin examination re- tion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicemia in immunocompromised vealed three 3-12–mm, tender, indurated, and erythematous papules patients. -

329 Abscesses, 17, 189. See Also Carbuncles

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89729-7 - Skin Infections: Diagnosis and Treatment Edited by John C. Hall and Brian J. Hall Index More information I n d e x abscesses, 17, 189. See also carbuncles; acute infections, primary signs of, 8 American Th oracic Society, 292 furuncles acute miliary cutaneous tuberculosis, 60, 74 American trypanosomiasis, 123 acanthamebiasis, in HIV infection, 193–194 acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, amikacin with tetracycline, for Acanthamoeba spp., 121 294–295 protothecosis, 175 Acanthaster planci (crown of thorns) starfi sh, acute paronychial infections, 268–269 aminoglycosides 173 acyclovir for ecthyma gangrenosum, 215 acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccination, 294 for congenital herpes simplex, 30 for nocardiosis, 198 acetaminophen, for HSV 1 and 2 infections, for genital herpes, 319 amitriptyline for post-herpetic neuralgia, 31 277 for hand-foot-and-mouth disease, 282 amorolfi ne Acinetobacter baumannii, 189 for herpes simplex virus, 200, 277 nail lacquers, for tinea unguium, 219 Ackerman, A. Bernard, 6 for herpes virus B, 34 topical, for tinea unguium, 236 acne miliaris necrotica, 262 for herpes zoster, 31 amoxicillin Acquired Immune Defi ciency Syndrome for HSV-1/HSV-2, 29 complications from, 33, 278–279 (AIDS). See also HIV-related skin oral, for HSV, 186 for genital bite wounds, 317 infections; Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) for oral hairy leukoplakia, 187, 279 for Lyme disease, 215 acid-fast bacilli in, 72 for suspected neonatal HSV, 225 for perianal streptococcal dermatitis, 212 anergy, presence of, -

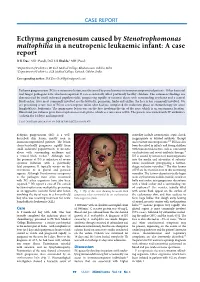

Ecthyma Gangrenosum Caused by Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia in a Neutropenic Leukaemic Infant: a Case Report D K Das,1 MD (Paed), DCH; S Shukla,2 MD (Paed)

CASE REPORT Ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in a neutropenic leukaemic infant: A case report D K Das,1 MD (Paed), DCH; S Shukla,2 MD (Paed) 1 Department of Pediatrics, Hi Tech Medical College, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India 2 Department of Pediatrics, SCB Medical College, Cuttack, Odisha, India Corresponding author: D K Das ([email protected]) Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a cutaneous lesion, mostly caused by pseudomonas in immunocompromised patients. Other bacterial and fungal pathogens have also been reported. It can occasionally affect previously healthy children. The cutaneous findings are characterised by small indurated papulovesicles, progressing rapidly to necrotic ulcers with surrounding erythema and a central black eschar. Sites most commonly involved are the buttocks, perineum, limbs and axillae; the face is less commonly involved. We are presenting a rare case of EG in a neutropenic infant who had just completed the induction phase of chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. The gangrenous lesion was on the face involving the tip of the nose, which is an uncommon location. Blood and pus cultures grew Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, which is a rare cause of EG. The patient was treated with IV antibiotics (colistin for 14 days) and improved. S Afr J Child Health 2016;10(1):99-100. DOI:10.7196/SAJCH.2016.v10i1.957 Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a well- mortality include neutropenia, septic shock, described skin lesion, mostly seen in inappropriate or delayed antibiotic therapy immunocompromised patients.