Dermatology in the ER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skin Microbiota: a Source of Disease Or Defence? A.L

FROM BENCH TO BEDSIDE DOI 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08437.x Skin microbiota: a source of disease or defence? A.L. Cogen,* V. Nizetৠand R.L. Gallo à Departments of *Bioengineering, Medicine, Division of Dermatology and àPediatrics, School of Medicine, and §Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of California, San Diego, CA, U.S.A. Summary Correspondence Microbes found on the skin are usually regarded as pathogens, potential patho- Richard L. Gallo. gens or innocuous symbiotic organisms. Advances in microbiology and immu- E-mail: [email protected] nology are revising our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of microbial virulence and the specific events involved in the host–microbe interaction. Cur- Accepted for publication 30 September 2007 rent data contradict some historical classifications of cutaneous microbiota and suggest that these organisms may protect the host, defining them not as simple Key words symbiotic microbes but rather as mutualistic. This review will summarize current bacteria, immunity, infectious disease information on bacterial skin flora including Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, Propioni- bacterium, Streptococcus and Pseudomonas. Specifically, the review will discuss our cur- Conflicts of interest rent understanding of the cutaneous microbiota as well as shifting paradigms in None declared. the interpretation of the roles microbes play in skin health and disease. Most scholarly reviews of skin microbiota concentrate on ence inflammatory bowel disease,2 and how lactobacilli in the understanding the population structure of the flora inhabiting intestine educate prenatal immune responses. These findings the skin, or how a subset of these microbes can become complement several studies that suggest disruption in micro- human pathogens. -

Bacterial Pseudomycetoma (Botryomycosis) in an FIV-Positive Cat

獣医臨床皮膚科 16 (2): 61–65, 2010 Case Report Bacterial Pseudomycetoma (Botryomycosis) in an FIV-positive Cat FIV陽性猫にみられた細菌性偽菌腫(ボトリオミセス症)の1例 Tae Murai1)*, Kyohei Yasuno2), Kinji Shirota2, 3) 1)Kinder-Care Veterinary Clinic, 2)Research Institute of Biosciences and 3)Laboratory of Veterinary Pathology, Azabu University 村井 妙 1)* 安野恭平 2) 代田欣二 2, 3) 1)キンダーケア動物病院,2)麻布大学附置生物科学総合研究所,3)麻布大学獣医病理学研究室 Abstract: A 2.5-year-old spayed female domestic short-haired cat presented with more than a month’s history of a thickly crusted, purulent draining lesion on the shoulder area. Prior to the lesion’s formation, the cat had been repeatedly scratching the shoulder. Histological examination of skin biopsy specimens revealed both discrete and confluent pyogranulomas with fibroplasias and characteristic granules composed of gram-positive cocci surrounded by an eosinophilic amorphous substance. The histopathological findings were consistent with bacterial pseudomycetoma. The skin lesion was successfully treated with systemic and topical administration of antibiotics for about 4 months. However, occasional scratching continued, leading to the development of a small erosion in the same area. The present cat was antigen-positive for feline immunodeficiency virus, and it showed symptoms potentially caused by feline immunodeficiency syndrome. Decreased immune competence might contribute to the pathogenesis of bacterial pseudomycetoma. Key words: bacterial pseudomycetoma, botryomycosis, cat 要 約:2.5歳齢,避妊済みの雑種猫が,頚背部に著しく厚い痂疲を伴う排膿性皮疹を呈し来院した。 病変は当初激しいそう痒から始まり,やがて掻爬部位に一致して瘻孔の形成を認めた。病変部の病 -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

Pseudomonas Skin Infection Clinical Features, Epidemiology, and Management

Am J Clin Dermatol 2011; 12 (3): 157-169 THERAPY IN PRACTICE 1175-0561/11/0003-0157/$49.95/0 ª 2011 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Pseudomonas Skin Infection Clinical Features, Epidemiology, and Management Douglas C. Wu,1 Wilson W. Chan,2 Andrei I. Metelitsa,1 Loretta Fiorillo1 and Andrew N. Lin1 1 Division of Dermatology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada 2 Department of Laboratory Medicine, Medical Microbiology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Contents Abstract........................................................................................................... 158 1. Introduction . 158 1.1 Microbiology . 158 1.2 Pathogenesis . 158 1.3 Epidemiology: The Rise of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ............................................................. 158 2. Cutaneous Manifestations of P. aeruginosa Infection. 159 2.1 Primary P. aeruginosa Infections of the Skin . 159 2.1.1 Green Nail Syndrome. 159 2.1.2 Interdigital Infections . 159 2.1.3 Folliculitis . 159 2.1.4 Infections of the Ear . 160 2.2 P. aeruginosa Bacteremia . 160 2.2.1 Subcutaneous Nodules as a Sign of P. aeruginosa Bacteremia . 161 2.2.2 Ecthyma Gangrenosum . 161 2.2.3 Severe Skin and Soft Tissue Infection (SSTI): Gangrenous Cellulitis and Necrotizing Fasciitis. 161 2.2.4 Burn Wounds . 162 2.2.5 AIDS................................................................................................. 162 2.3 Other Cutaneous Manifestations . 162 3. Antimicrobial Therapy: General Principles . 163 3.1 The Development of Antibacterial Resistance . 163 3.2 Anti-Pseudomonal Agents . 163 3.3 Monotherapy versus Combination Therapy . 164 4. Antimicrobial Therapy: Specific Syndromes . 164 4.1 Primary P. aeruginosa Infections of the Skin . 164 4.1.1 Green Nail Syndrome. 164 4.1.2 Interdigital Infections . 165 4.1.3 Folliculitis . -

CHAPTER E16 Atlas of Skin Manifestations of Internal Disease CHAPTER E16 Thomas J

CHAPTER e16 Atlas of Skin Manifestations of Internal Disease CHAPTER e16 Thomas J. Lawley Robert A. Swerlick In the practice of medicine, virtually every clinician encounters patients with skin disease. Physicians of all specialties face the daily task of determining the nature and clinical implication of dermatologic disease. In patients with skin eruptions and rashes, the physician must confront the question of whether the cutaneous Atlas of Skin Manifestations Internal Disease process is confined to the skin, representing a pure dermatologic event, or whether it is a manifestation of internal disease relating to the patient’s overall medical condition. Evaluation and accurate diagnosis of skin lesions are also critical given the marked rise in both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatologic conditions can be classified and categorized in many different ways, Figure e16-2 Acne rosacea with prominent facial erythema, telangiecta- and in this Atlas, a selected group of inflammatory skin eruptions sias, scattered papules, and small pustules. (Courtesy of Robert Swerlick, and neoplastic conditions are grouped in the following manner: MD; with permission.) (A) common skin diseases and lesions, (B) nonmelanoma skin cancer, (C) melanoma and pigmented lesions, (D) infectious dis- ease and the skin, (E) immunologically mediated skin disease, and (F) skin manifestations of internal disease. COMMON SKIN DISEASES AND LESIONS ( Figs. e16-1 to e16-19) In this section, several common inflamma- tory skin diseases and benign neoplastic and reactive lesions are presented. While most of these dermatoses usually present as a pre- dominantly dermatologic process, underlying systemic associations may be made in some settings. Atopic dermatitis is often present in patients with an atopic diathesis, including asthma and sinusitis. -

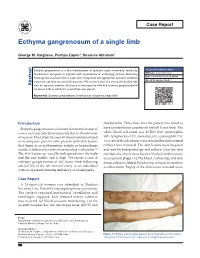

Ecthyma Gangrenosum of a Single Limb

Case Report Ecthyma gangrenosum of a single limb George M. Varghese, Pushpa Eapen1, Susanne Abraham1 Ecthyma gangrenosum is a skin manifestation of systemic sepsis commonly caused by Access this article online Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with neutropenia or underlying immune deficiency. Website: www.ijccm.org Although the usual outcome is poor, early recognition and appropriate systemic antibiotic DOI: 10.4103/0972-5229.84898 treatment can lead to successful outcome. We report a case of a previously healthy lady Quick Response Code: Abstract with no apparent immune deficiency or neutropenia who had ecthyma gangrenosum of left lower limb in which the arterial line was placed. Keywords: Ecthyma gangrenosum, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, single limb Introduction thachycardia. Three days later the patient was noted to Ecthyma gangrenosum is a known skin manifestation of have erythematous papules on the left lower limb. The 3 severe systemic infection commonly due to Pseudomonas white blood cell count was 16,500/mm (neutrophils aeruginosa. Most often it is seen in immunocompromised 84%, lymphocytes 12%, monocytes 3%, eosinophils 1%). or neutropenic patients who present with skin lesions Two sets of blood cultures were sent and the intra-arterial that begin as an erythematous nodule or hemorrhagic catheter was removed. The skin lesions were biopsied vesicle, which evolves into a necrotic ulcer with eschar. [1] and sent for histopathology and culture. Over the next The skin lesions are usually widespread over the body few days the skin lesions became blackish with necrotic and the case fatality rate is high. We report a case of areas (arrow) [Figure 1]. The blood, catheter tip, and skin ecthyma gangrenosum of left lower limb following lesion cultures yielded Pseudomonas aeruginosa sensitive arterial line in the left femoral artery in an individual to ceftazidime. -

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections Following Marine Injuries

CHAPTER 6 Skin and Soft Tissue Infections Following Marine Injuries V. Savini, R. Marrollo, R. Nigro, C. Fusella, P. Fazii Spirito Santo Hospital, Pescara, Italy 1. INTRODUCTION Bacterial diseases following aquatic injuries occur frequently worldwide and usually develop on the extremities of fishermen and vacationers, who are exposed to freshwater and saltwater.1,2 Though plenty of bacterial species have been isolated from marine lesions, superficial soft tissue and invasive systemic infections after aquatic injuries and exposures are related to a restricted number of microorganisms including, in alphabetical order, Aeromonas hydrophila, Chromobacterium violaceum, Edwardsiella tarda, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, Myco- bacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium marinum, Shewanella species, Streptococcus iniae, and Vibrio vulnificus.1,2 In particular, skin disorders represent the third most common cause of morbidity in returning travelers and are usually represented by bacterial infections.3–12 Bacterial skin and soft tissue infectious conditions in travelers often follow insect bites and can show a wide range of clinical pictures including impetigo, ecthyma, erysipelas, abscesses, necro- tizing cellulitis, myonecrosis.3–12 In general, even minor abrasions and lacerations sustained in marine waters should be considered potentially contaminated with marine bacteria.3–12 Despite variability of the causative agents and outcomes, the initial presentations of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) complicating marine injuries are similar to those occurring after terrestrial exposures and usually include erysipelas, impetigo, cellulitis, and necrotizing infections.3 Erysipelas is characterized by fiery red, tender, painful plaques showing well-demarcated edges, and, though Streptococcus pyogenes is the major agent of this pro- cess, E. rhusiopathiae infections typically cause erysipeloid displays.3 Impetigo is initially characterized by bullous lesions and is usually due to Staphylococcus aureus or S. -

Pediatric Cutaneous Bacterial Infections Dr

PEDIATRIC CUTANEOUS BACTERIAL INFECTIONS DR. PEARL C. KWONG MD PHD BOARD CERTIFIED PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGIST JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA DISCLOSURE • No relevant relationships PRETEST QUESTIONS • In Staph scalded skin syndrome: • A. The staph bacteria can be isolated from the nares , conjunctiva or the perianal area • B. The patients always have associated multiple system involvement including GI hepatic MSK renal and CNS • C. common in adults and adolescents • D. can also be caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa • E. None of the above PRETEST QUESTIONS • Scarlet fever • A. should be treated with penicillins • B. should be treated with sulfa drugs • C. can lead to toxic shock syndrome • D. can be associated with pharyngitis or circumoral pallor • E. Both A and D are correct PRETEST QUESTIONS • Strep can be treated with the following antibiotics • A. Penicillin • B. First generation cephalosporin • C. clindamycin • D. Septra • E. A B or C • F. A and D only PRETEST QUESTIONS • MRSA • A. is only acquired via hospital • B. can be acquired in the community • C. is more aggressive than OSSA • D. needs treatment with first generation cephalosporin • E. A and C • F. B and C CUTANEOUS BACTERIAL PATHOGENS • Staphylococcus aureus: OSSA and MRSA • Gp A Streptococcus GABHS • Pseudomonas aeruginosa CUTANEOUS BACTERIAL INFECTIONS • Folliculitis • Non bullous Impetigo/Bullous Impetigo • Furuncle/Carbuncle/Abscess • Cellulitis • Acute Paronychia • Dactylitis • Erysipelas • Impetiginization of dermatoses BACTERIAL INFECTION • Important to diagnose early • Almost always -

| Oa Tai Ei Rama Telut Literatur

|OA TAI EI US009750245B2RAMA TELUT LITERATUR (12 ) United States Patent ( 10 ) Patent No. : US 9 ,750 ,245 B2 Lemire et al. ( 45 ) Date of Patent : Sep . 5 , 2017 ( 54 ) TOPICAL USE OF AN ANTIMICROBIAL 2003 /0225003 A1 * 12 / 2003 Ninkov . .. .. 514 / 23 FORMULATION 2009 /0258098 A 10 /2009 Rolling et al. 2009 /0269394 Al 10 /2009 Baker, Jr . et al . 2010 / 0034907 A1 * 2 / 2010 Daigle et al. 424 / 736 (71 ) Applicant : Laboratoire M2, Sherbrooke (CA ) 2010 /0137451 A1 * 6 / 2010 DeMarco et al. .. .. .. 514 / 705 2010 /0272818 Al 10 /2010 Franklin et al . (72 ) Inventors : Gaetan Lemire , Sherbrooke (CA ) ; 2011 / 0206790 AL 8 / 2011 Weiss Ulysse Desranleau Dandurand , 2011 /0223114 AL 9 / 2011 Chakrabortty et al . Sherbrooke (CA ) ; Sylvain Quessy , 2013 /0034618 A1 * 2 / 2013 Swenholt . .. .. 424 /665 Ste - Anne -de - Sorel (CA ) ; Ann Letellier , Massueville (CA ) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS ( 73 ) Assignee : LABORATOIRE M2, Sherbrooke, AU 2009235913 10 /2009 CA 2567333 12 / 2005 Quebec (CA ) EP 1178736 * 2 / 2004 A23K 1 / 16 WO WO0069277 11 /2000 ( * ) Notice : Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this WO WO 2009132343 10 / 2009 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 WO WO 2010010320 1 / 2010 U . S . C . 154 ( b ) by 37 days . (21 ) Appl. No. : 13 /790 ,911 OTHER PUBLICATIONS Definition of “ Subject ,” Oxford Dictionary - American English , (22 ) Filed : Mar. 8 , 2013 Accessed Dec . 6 , 2013 , pp . 1 - 2 . * Inouye et al , “ Combined Effect of Heat , Essential Oils and Salt on (65 ) Prior Publication Data the Fungicidal Activity against Trichophyton mentagrophytes in US 2014 /0256826 A1 Sep . 11, 2014 Foot Bath ,” Jpn . -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Pseudo by Dysonrules

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Pseudo by dysonrules Pseudoreplication: choose your data wisely¶ Many studies strive to collect more data through replication: by repeating their measurements with additional patients or samples, they can be more certain of their numbers and discover subtle relationships that aren’t obvious at first glance. We’ve seen the value of additional data for improving statistical power and detecting small differences. But what exactly counts as a replication? Let’s return to a medical example. I have two groups of 100 patients taking different medications, and I seek to establish which medication lowers blood pressure more. I have each group take the medication for a month to allow it to take effect, and then I follow each group for ten days, each day testing their blood pressure. I now have ten data points per patient and 1,000 data points per group. Brilliant! 1,000 data points is quite a lot, and I can fairly easily establish whether one group has lower blood pressure than the other. When I do calculations for statistical significance I find significant results very easily. But wait: we expect that taking a patient’s blood pressure ten times will yield ten very similar results. If one patient is genetically predisposed to low blood pressure, I have counted his genetics ten times. Had I collected data from 1,000 independent patients instead of repeatedly testing 100, I would be more confident that differences between groups came from the medicines and not from genetics and luck. I claimed a large sample size, giving me statistically significant results and high statistical power, but my claim is unjustified. -

Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host

Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host Marc E. Grossman • Lindy P. Fox • Carrie Kovarik Misha Rosenbach Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host Second Edition Authors Marc E. Grossman, M.D. Carrie Kovarik, M.D. Professor of Clinical Dermatology Assistant Professor of Dermatology College of Physicians and Surgeons Dermatopathology, and Infectious Diseases Director, Hospital Consultation Service University of Pennsylvania New York Presbyterian Hospital Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Columbia University Medical Center New York, New York, USA Misha Rosenbach, M.D. Assistant Professor of Dermatology Lindy P. Fox, M.D. and Internal Medicine Associate Professor of Clinical Dermatology Director, Dermatology Inpatient Consult Service Director, Hospital Consultation Service University of Pennsylvania University of California, San Francisco Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA San Francisco, California, USA ISBN 978-1-4419-1577-1 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-1578-8 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-1578-8 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Library of Congress Control Number: 2011933837 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2012 All rights reserved. Th is work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter devel- oped is forbidden. Th e use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identifi ed as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. -

Abdominal Distension, 284 Abdominal Mass, Hydatid Disease, 287

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-69761-3 - Case Studies in Pediatric Infectious Diseases Frank E. Berkowitz Index More information Index Abdominal distension, 284 perivenous, 240 Abdominal mass, hydatid disease, psoas 287 tuberculosis, 226 Abdominal pain, 12, 79, 112, 158, 169, 177, retropharyngeal, 100, 264, 318 257, 270, 273, 304, 308 tuberculosis, 226 acute HIV infection, 311 spinal epidural, 273 appendicitis, 253 spinal cat-scratch disease, 143 paraplegia, 262 hydatid disease, 287 subphrenic, 232 leptospirosis, 139 tubo-ovarian, 322 pelvic inflammatory disease, 319 Absidia, taxonomy, 347 peritonitis, 315 Acanthameba, taxonomy, 348 pneumonia, 248 Acetaminophen, 15, 54 pyelonephritis, 244 Acetylcholine, 129 typhus, 149 Acid-fast bacilli See Mycobacteria Abdominal tenderness, 257 Acidosis, diarrhea, 80 Abscess Acinetobacter, taxonomy, 342 appendix, 159, 255 Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, 146, brain, 43, 66, 255 193, 210, 242 meningitis, 108 reportable, 336 seizure, 195 Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, 153 Brodie’s, 282 taxonomy, 343 cerebellar, 327 infective endocarditis, 297 dental, 271 Actinomyces, 124, 127 epidural, 334 taxonomy, 344 eye, 314 Actinomyces israelii, 125 lateral pharyngeal, 264 Actinomyces odontolyticus, taxonomy, liver, 13, 174 344 amebic, 174 Actinomycosis, 125 lung, 249 Acute chest syndrome, sickle cell disease, 249, odontogenic See Abscess 324 dental Acyclovir, 42 pelvic, 306 Epstein–Barr virus, 39 peritonsillar, 100, 264 herpes simplex virus, 29 Lemierre syndrome, 332 varicella, 47 355 © Cambridge University