The Acutely Ill Patient with Fever and Rash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Microbiological, Clinical and Therapeutic Aspects of Impetigo Lior Zusmanovich, Lior Charach and Gideon Charach*

ISSN: 2378-3656 Zusmanovich et al. Clin Med Rev Case Rep 2018, 5:205 DOI: 10.23937/2378-3656/1410205 Volume 5 | Issue 3 Clinical Medical Reviews Open Access and Case Reports CASE REPORT Current Microbiological, Clinical and Therapeutic Aspects of Impetigo Lior Zusmanovich, Lior Charach and Gideon Charach* Department of Internal Medicine “C”, Affiliated to Tel Aviv University, Israel *Corresponding author: Gideon Charach, Department of Internal Medicine “C”, Tel Aviv Sourasky Check for Medical Center, Sackler Medical School, Affiliated to Tel Aviv University, 6 Weizman Street, Tel Aviv updates 6423906, Israel, Tel: +972-3-6973766, Fax: +972-3-6973929, E-mail: [email protected] nonpurulent and purulent cellulitis, and treatment is Abstract based on extent of infection and risk factors. Abscesses Impetigo is a highly contagious infection of the epidermis, involve the dermis and deeper skin tissues as a result of seen especially among children, and transmitted through direct contact. Two bacteria are associated with impetigo: pus formation. S. aureus and GAS. Over 140 million people are suffering Impetigo is observed most frequently among chil- from impetigo at each time point, over 100 million are chil- dren. Two forms of impetigo exist, namely impetigo conta- dren 2-5 years of age and is transmitted through direct giosa, known as the non-bullous form and the second one contact [1]. Risk factors for impetigo include poor hy- being bullous impetigo which presents with large and fragile giene, low economic status, crowding and underlying bullae. Treatment options for impetigo include systemic an- scabies [2,3]. Important consideration is carriage of tibiotics, topical antibiotics as well as topical disinfectants. -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

Bacterial Infections Diseases Picture Cause Basic Lesion

page: 117 Chapter 6: alphabetical Bacterial infections diseases picture cause basic lesion search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Impetigo page: 118 6.1 Impetigo alphabetical Bullous impetigo Bullae with cloudy contents, often surrounded by an erythematous halo. These bullae rupture easily picture and are rapidly replaced by extensive crusty patches. Bullous impetigo is classically caused by Staphylococcus aureus. cause basic lesion Basic Lesions: Bullae; Crusts Causes: Infection search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Impetigo page: 119 alphabetical Non-bullous impetigo Erythematous patches covered by a yellowish crust. Lesions are most frequently around the mouth. picture Lesions around the nose are very characteristic and require prolonged treatment. ß-Haemolytic streptococcus is cause most frequently found in this type of impetigo. basic lesion Basic Lesions: Erythematous Macule; Crusts Causes: Infection search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Ecthyma page: 120 6.2 Ecthyma alphabetical Slow and gradually deepening ulceration surmounted by a thick crust. The usual site of ecthyma are the legs. After healing there is a permanent scar. The pathogen is picture often a streptococcus. Ecthyma is very common in tropical countries. cause basic lesion Basic Lesions: Crusts; Ulcers Causes: Infection search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Folliculitis page: 121 6.3 Folliculitis -

Pseudomonas Skin Infection Clinical Features, Epidemiology, and Management

Am J Clin Dermatol 2011; 12 (3): 157-169 THERAPY IN PRACTICE 1175-0561/11/0003-0157/$49.95/0 ª 2011 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Pseudomonas Skin Infection Clinical Features, Epidemiology, and Management Douglas C. Wu,1 Wilson W. Chan,2 Andrei I. Metelitsa,1 Loretta Fiorillo1 and Andrew N. Lin1 1 Division of Dermatology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada 2 Department of Laboratory Medicine, Medical Microbiology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Contents Abstract........................................................................................................... 158 1. Introduction . 158 1.1 Microbiology . 158 1.2 Pathogenesis . 158 1.3 Epidemiology: The Rise of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ............................................................. 158 2. Cutaneous Manifestations of P. aeruginosa Infection. 159 2.1 Primary P. aeruginosa Infections of the Skin . 159 2.1.1 Green Nail Syndrome. 159 2.1.2 Interdigital Infections . 159 2.1.3 Folliculitis . 159 2.1.4 Infections of the Ear . 160 2.2 P. aeruginosa Bacteremia . 160 2.2.1 Subcutaneous Nodules as a Sign of P. aeruginosa Bacteremia . 161 2.2.2 Ecthyma Gangrenosum . 161 2.2.3 Severe Skin and Soft Tissue Infection (SSTI): Gangrenous Cellulitis and Necrotizing Fasciitis. 161 2.2.4 Burn Wounds . 162 2.2.5 AIDS................................................................................................. 162 2.3 Other Cutaneous Manifestations . 162 3. Antimicrobial Therapy: General Principles . 163 3.1 The Development of Antibacterial Resistance . 163 3.2 Anti-Pseudomonal Agents . 163 3.3 Monotherapy versus Combination Therapy . 164 4. Antimicrobial Therapy: Specific Syndromes . 164 4.1 Primary P. aeruginosa Infections of the Skin . 164 4.1.1 Green Nail Syndrome. 164 4.1.2 Interdigital Infections . 165 4.1.3 Folliculitis . -

CHAPTER E16 Atlas of Skin Manifestations of Internal Disease CHAPTER E16 Thomas J

CHAPTER e16 Atlas of Skin Manifestations of Internal Disease CHAPTER e16 Thomas J. Lawley Robert A. Swerlick In the practice of medicine, virtually every clinician encounters patients with skin disease. Physicians of all specialties face the daily task of determining the nature and clinical implication of dermatologic disease. In patients with skin eruptions and rashes, the physician must confront the question of whether the cutaneous Atlas of Skin Manifestations Internal Disease process is confined to the skin, representing a pure dermatologic event, or whether it is a manifestation of internal disease relating to the patient’s overall medical condition. Evaluation and accurate diagnosis of skin lesions are also critical given the marked rise in both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatologic conditions can be classified and categorized in many different ways, Figure e16-2 Acne rosacea with prominent facial erythema, telangiecta- and in this Atlas, a selected group of inflammatory skin eruptions sias, scattered papules, and small pustules. (Courtesy of Robert Swerlick, and neoplastic conditions are grouped in the following manner: MD; with permission.) (A) common skin diseases and lesions, (B) nonmelanoma skin cancer, (C) melanoma and pigmented lesions, (D) infectious dis- ease and the skin, (E) immunologically mediated skin disease, and (F) skin manifestations of internal disease. COMMON SKIN DISEASES AND LESIONS ( Figs. e16-1 to e16-19) In this section, several common inflamma- tory skin diseases and benign neoplastic and reactive lesions are presented. While most of these dermatoses usually present as a pre- dominantly dermatologic process, underlying systemic associations may be made in some settings. Atopic dermatitis is often present in patients with an atopic diathesis, including asthma and sinusitis. -

Ecthyma Gangrenosum of a Single Limb

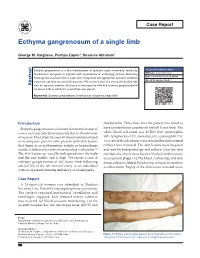

Case Report Ecthyma gangrenosum of a single limb George M. Varghese, Pushpa Eapen1, Susanne Abraham1 Ecthyma gangrenosum is a skin manifestation of systemic sepsis commonly caused by Access this article online Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with neutropenia or underlying immune deficiency. Website: www.ijccm.org Although the usual outcome is poor, early recognition and appropriate systemic antibiotic DOI: 10.4103/0972-5229.84898 treatment can lead to successful outcome. We report a case of a previously healthy lady Quick Response Code: Abstract with no apparent immune deficiency or neutropenia who had ecthyma gangrenosum of left lower limb in which the arterial line was placed. Keywords: Ecthyma gangrenosum, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, single limb Introduction thachycardia. Three days later the patient was noted to Ecthyma gangrenosum is a known skin manifestation of have erythematous papules on the left lower limb. The 3 severe systemic infection commonly due to Pseudomonas white blood cell count was 16,500/mm (neutrophils aeruginosa. Most often it is seen in immunocompromised 84%, lymphocytes 12%, monocytes 3%, eosinophils 1%). or neutropenic patients who present with skin lesions Two sets of blood cultures were sent and the intra-arterial that begin as an erythematous nodule or hemorrhagic catheter was removed. The skin lesions were biopsied vesicle, which evolves into a necrotic ulcer with eschar. [1] and sent for histopathology and culture. Over the next The skin lesions are usually widespread over the body few days the skin lesions became blackish with necrotic and the case fatality rate is high. We report a case of areas (arrow) [Figure 1]. The blood, catheter tip, and skin ecthyma gangrenosum of left lower limb following lesion cultures yielded Pseudomonas aeruginosa sensitive arterial line in the left femoral artery in an individual to ceftazidime. -

Skin Disease and Disorders

Sports Dermatology Robert Kiningham, MD, FACSM Department of Family Medicine University of Michigan Health System Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest ◼ None Goals and Objectives ◼ Review skin infections common in athletes ◼ Establish a logical treatment approach to skin infections ◼ Discuss ways to decrease the risk of athlete’s acquiring and spreading skin infections ◼ Discuss disqualification and return-to-play criteria for athletes with skin infections ◼ Recognize and treat non-infectious skin conditions in athletes Skin Infections in Athletes ◼ Bacterial ◼ Herpetic ◼ Fungal Skin Infections in Athletes ◼ Very common – most common cause of practice-loss time in wrestlers ◼ Athletes are susceptible because: – Prone to skin breakdown (abrasions, cuts) – Warm, moist environment – Close contacts Cases 1 -3 ◼ 21 year old male football player with 4 day h/o left axillary pain and tenderness. Two days ago he noticed a tender “bump” that is getting bigger and more tender. ◼ 16 year old football player with 3 day h/o mildly tender lesions on chin. Started as a single lesion, but now has “spread”. Over the past day the lesions have developed a dark yellowish crust. ◼ 19 year old wrestler with a 3 day h/o lesions on right side of face. Noticed “tingling” 4 days ago, small fluid filled lesions then appeared that have now started to crust over. Skin Infections Bacterial Skin Infections ◼ Cellulitis ◼ Erysipelas ◼ Impetigo ◼ Furunculosis ◼ Folliculitis ◼ Paronychea Cellulitis Cellulitis ◼ Diffuse infection of connective tissue with severe inflammation of dermal and subcutaneous layers of the skin – Triad of erythema, edema, and warmth in the absence of underlying foci ◼ S. aureus or S. pyogenes Erysipelas Erysipelas ◼ Superficial infection of the dermis ◼ Distinguished from cellulitis by the intracutaneous edema that produces palpable margins of the skin. -

Necrotizing Fasciitis Report of 39 Pediatric Cases

STUDY Necrotizing Fasciitis Report of 39 Pediatric Cases Antonio Fustes-Morales, MD; Pedro Gutierrez-Castrellon, MD; Carola Duran-Mckinster, MD; Luz Orozco-Covarrubias, MD; Lourdes Tamayo-Sanchez, MD; Ramon Ruiz-Maldonado, MD Background: Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a severe, Results: We examined 39 patients with NF (0.018% of life-threatening soft tissue infection. General features all hospitalized patients). Twenty-one patients (54%) were and risk factors for fatal outcome in children are not boys. Mean age was 4.4 years. Single lesions were seen in well known. 30 (77%) of patients, with 21(54%) in extremities. The most frequent preexisting condition was malnutrition in 14 pa- Objective: To characterize the features of NF in chil- tients (36%). The most frequent initiating factor was vari- dren and the risk factors for fatal outcome. cella in 13 patients (33%). Diagnosis of NF at admission was made in 11 patients (28%). Bacterial isolations in 24 Design: Retrospective, comparative, observational, and patients (62%) were polymicrobial in 17 (71%). Pseudo- longitudinal trial. monas aeruginosa was the most frequently isolated bacte- ria; gram-negative isolates, the most frequently associated Setting: Dermatology department of a tertiary care pe- bacteria. Complications were present in 33 patients (85%), diatric hospital. mortality in 7 (18%), and sequelae in 29 (91%) of 32 sur- viving patients. The significant risk factor related to a fatal Patients: All patients with clinical and/or histopatho- outcome was immunosuppression. logical diagnosis of NF seen from January 1, 1971, through December 31, 2000. Conclusions: Necrotizing fasciitis in children is fre- quently misdiagnosed, and several features differ from those Main Outcome Variables: Incidence, age, sex, num- of NF in adults. -

Z:\My Documents\WPDOCS\IACUC

ZOONOTIC DISEASES OF LABORATORY, AGRICULTURAL, AND WILDLIFE ANIMALS July, 2007 Michael S. Rand, DVM, DACLAM University Animal Care University of Arizona PO Box 245092 Tucson, AZ 85724-5092 (520) 626-6705 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.ahsc.arizona.edu/uac Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Amebiasis ............................................................................................................................................... 5 B Virus .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Balantidiasis ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Brucellosis ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Campylobacteriosis ................................................................................................................................ 7 Capnocytophagosis ............................................................................................................................ 8 Cat Scratch Disease ............................................................................................................................... 9 Chlamydiosis ..................................................................................................................................... -

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections Following Marine Injuries

CHAPTER 6 Skin and Soft Tissue Infections Following Marine Injuries V. Savini, R. Marrollo, R. Nigro, C. Fusella, P. Fazii Spirito Santo Hospital, Pescara, Italy 1. INTRODUCTION Bacterial diseases following aquatic injuries occur frequently worldwide and usually develop on the extremities of fishermen and vacationers, who are exposed to freshwater and saltwater.1,2 Though plenty of bacterial species have been isolated from marine lesions, superficial soft tissue and invasive systemic infections after aquatic injuries and exposures are related to a restricted number of microorganisms including, in alphabetical order, Aeromonas hydrophila, Chromobacterium violaceum, Edwardsiella tarda, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, Myco- bacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium marinum, Shewanella species, Streptococcus iniae, and Vibrio vulnificus.1,2 In particular, skin disorders represent the third most common cause of morbidity in returning travelers and are usually represented by bacterial infections.3–12 Bacterial skin and soft tissue infectious conditions in travelers often follow insect bites and can show a wide range of clinical pictures including impetigo, ecthyma, erysipelas, abscesses, necro- tizing cellulitis, myonecrosis.3–12 In general, even minor abrasions and lacerations sustained in marine waters should be considered potentially contaminated with marine bacteria.3–12 Despite variability of the causative agents and outcomes, the initial presentations of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) complicating marine injuries are similar to those occurring after terrestrial exposures and usually include erysipelas, impetigo, cellulitis, and necrotizing infections.3 Erysipelas is characterized by fiery red, tender, painful plaques showing well-demarcated edges, and, though Streptococcus pyogenes is the major agent of this pro- cess, E. rhusiopathiae infections typically cause erysipeloid displays.3 Impetigo is initially characterized by bullous lesions and is usually due to Staphylococcus aureus or S. -

Pediatric Cutaneous Bacterial Infections Dr

PEDIATRIC CUTANEOUS BACTERIAL INFECTIONS DR. PEARL C. KWONG MD PHD BOARD CERTIFIED PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGIST JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA DISCLOSURE • No relevant relationships PRETEST QUESTIONS • In Staph scalded skin syndrome: • A. The staph bacteria can be isolated from the nares , conjunctiva or the perianal area • B. The patients always have associated multiple system involvement including GI hepatic MSK renal and CNS • C. common in adults and adolescents • D. can also be caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa • E. None of the above PRETEST QUESTIONS • Scarlet fever • A. should be treated with penicillins • B. should be treated with sulfa drugs • C. can lead to toxic shock syndrome • D. can be associated with pharyngitis or circumoral pallor • E. Both A and D are correct PRETEST QUESTIONS • Strep can be treated with the following antibiotics • A. Penicillin • B. First generation cephalosporin • C. clindamycin • D. Septra • E. A B or C • F. A and D only PRETEST QUESTIONS • MRSA • A. is only acquired via hospital • B. can be acquired in the community • C. is more aggressive than OSSA • D. needs treatment with first generation cephalosporin • E. A and C • F. B and C CUTANEOUS BACTERIAL PATHOGENS • Staphylococcus aureus: OSSA and MRSA • Gp A Streptococcus GABHS • Pseudomonas aeruginosa CUTANEOUS BACTERIAL INFECTIONS • Folliculitis • Non bullous Impetigo/Bullous Impetigo • Furuncle/Carbuncle/Abscess • Cellulitis • Acute Paronychia • Dactylitis • Erysipelas • Impetiginization of dermatoses BACTERIAL INFECTION • Important to diagnose early • Almost always -

| Oa Tai Ei Rama Telut Literatur

|OA TAI EI US009750245B2RAMA TELUT LITERATUR (12 ) United States Patent ( 10 ) Patent No. : US 9 ,750 ,245 B2 Lemire et al. ( 45 ) Date of Patent : Sep . 5 , 2017 ( 54 ) TOPICAL USE OF AN ANTIMICROBIAL 2003 /0225003 A1 * 12 / 2003 Ninkov . .. .. 514 / 23 FORMULATION 2009 /0258098 A 10 /2009 Rolling et al. 2009 /0269394 Al 10 /2009 Baker, Jr . et al . 2010 / 0034907 A1 * 2 / 2010 Daigle et al. 424 / 736 (71 ) Applicant : Laboratoire M2, Sherbrooke (CA ) 2010 /0137451 A1 * 6 / 2010 DeMarco et al. .. .. .. 514 / 705 2010 /0272818 Al 10 /2010 Franklin et al . (72 ) Inventors : Gaetan Lemire , Sherbrooke (CA ) ; 2011 / 0206790 AL 8 / 2011 Weiss Ulysse Desranleau Dandurand , 2011 /0223114 AL 9 / 2011 Chakrabortty et al . Sherbrooke (CA ) ; Sylvain Quessy , 2013 /0034618 A1 * 2 / 2013 Swenholt . .. .. 424 /665 Ste - Anne -de - Sorel (CA ) ; Ann Letellier , Massueville (CA ) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS ( 73 ) Assignee : LABORATOIRE M2, Sherbrooke, AU 2009235913 10 /2009 CA 2567333 12 / 2005 Quebec (CA ) EP 1178736 * 2 / 2004 A23K 1 / 16 WO WO0069277 11 /2000 ( * ) Notice : Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this WO WO 2009132343 10 / 2009 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 WO WO 2010010320 1 / 2010 U . S . C . 154 ( b ) by 37 days . (21 ) Appl. No. : 13 /790 ,911 OTHER PUBLICATIONS Definition of “ Subject ,” Oxford Dictionary - American English , (22 ) Filed : Mar. 8 , 2013 Accessed Dec . 6 , 2013 , pp . 1 - 2 . * Inouye et al , “ Combined Effect of Heat , Essential Oils and Salt on (65 ) Prior Publication Data the Fungicidal Activity against Trichophyton mentagrophytes in US 2014 /0256826 A1 Sep . 11, 2014 Foot Bath ,” Jpn .