Masks of Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018/2019 Season

Saturday, April 6, 2019 1:00 & 6:30 pm 2018/2019 SEASON Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. Kevin McKenzie Kara Medoff Barnett ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Alexei Ratmansky ARTIST IN RESIDENCE STELLA ABRERA ISABELLA BOYLSTON MISTY COPELAND HERMAN CORNEJO SARAH LANE ALBAN LENDORF GILLIAN MURPHY HEE SEO CHRISTINE SHEVCHENKO DANIIL SIMKIN CORY STEARNS DEVON TEUSCHER JAMES WHITESIDE SKYLAR BRANDT ZHONG-JING FANG THOMAS FORSTER JOSEPH GORAK ALEXANDRE HAMMOUDI BLAINE HOVEN CATHERINE HURLIN LUCIANA PARIS CALVIN ROYAL III ARRON SCOTT CASSANDRA TRENARY KATHERINE WILLIAMS ROMAN ZHURBIN Alexei Agoudine Joo Won Ahn Mai Aihara Nastia Alexandrova Sierra Armstrong Alexandra Basmagy Hanna Bass Aran Bell Gemma Bond Lauren Bonfiglio Kathryn Boren Zimmi Coker Luigi Crispino Claire Davison Brittany DeGrofft* Scout Forsythe Patrick Frenette April Giangeruso Carlos Gonzalez Breanne Granlund Kiely Groenewegen Melanie Hamrick Sung Woo Han Courtlyn Hanson Emily Hayes Simon Hoke Connor Holloway Andrii Ishchuk Anabel Katsnelson Jonathan Klein Erica Lall Courtney Lavine Virginia Lensi Fangqi Li Carolyn Lippert Isadora Loyola Xuelan Lu Duncan Lyle Tyler Maloney Hannah Marshall Betsy McBride Cameron McCune João Menegussi Kaho Ogawa Garegin Pogossian Lauren Post Wanyue Qiao Luis Ribagorda Rachel Richardson Javier Rivet Jose Sebastian Gabe Stone Shayer Courtney Shealy Kento Sumitani Nathan Vendt Paulina Waski Marshall Whiteley Stephanie Williams Remy Young Jin Zhang APPRENTICES Jacob Clerico Jarod Curley Michael de la Nuez Léa Fleytoux Abbey Marrison Ingrid Thoms Clinton Luckett ASSISTANT ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Ormsby Wilkins MUSIC DIRECTOR Charles Barker David LaMarche PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR CONDUCTOR PRINCIPAL BALLET MISTRESS Susan Jones BALLET MASTERS Irina Kolpakova Carlos Lopez Nancy Raffa Keith Roberts *2019 Jennifer Alexander Dancer ABT gratefully acknowledges: Avery and Andrew F. -

Education, Society and the Individual

CHAPTER 4 EDUCATION, SOCIETY AND THE INDIVIDUAL INTRODUCTION Hesse placed supreme importance on the value of the individual. From his youth he had rebelled against the imposition of social authority on the individual, and he continued this resistance throughout his adult life. The First World War had a profound impact on his thinking and writing. He described this as a ‘cruel awakening’ (Hesse, 1974c, p. 10) and in the years following the War he found himself utterly at odds with the spirit of his times in his native Germany. He spent much of his life in Switzerland. Hesse saw himself as an ‘unpolitical man’ and even when writing about the War, he wanted to guide the reader ‘not into the world theatre with its political problems but into his innermost being, before the judgement seat of his very personal conscience’ (p. 11). In Hesse’s novels and short stories, many of which have an educational focus, the theme of individual spiritual striving is paramount. His early novel, Peter Camenzind (Hesse, 1969), provides a fictionalised biographical account of the title character’s life, from his early years in the mountains, through his time as a student and his development as a writer, to his later life of devotion to a disabled friend and his elderly father. Beneath the Wheel (Hesse, 1968b) details the traumatic school experiences and tragic post-school life of a talented student. Siddhartha (Hesse, 2000a) takes the title character on a journey of self-discovery, with an exploration of dramatically different modes of life: asceticism, the world of business, sexual liberation, and oneness with nature, among others. -

Ut Pictora Poesis Hermann Hesse As a Poet and Painter

© HHP & C.I.Schneider, 1998 Posted 5/22/98 GG Ut Pictora Poesis Hermann Hesse as a Poet and Painter by Christian Immo Schneider Central Washington University Ellensburg, WA, U.S.A. Hermann Hesse stands in the international tradition of writers who are capable of expressing themselves in several arts. To be sure, he became famous first of all for his lyrical poetry and prose. How- ever, his thought and language is thoroughly permeated from his ear- liest to his last works with a profound sense of music. Great art- ists possess the specific gift of shifting their creative power from one to another medium. Therefore, it seems to be quite natural that Hesse, when he had reached a stage in his self-development which ne- cessitated both revitalization and enrichment of the art in which he had thus excelled, turned to painting as a means of the self expres- sion he had not yet experienced. "… one day I discovered an entirely new joy. Suddenly, at the age of forty, I began to paint. Not that I considered myself a painter or intended to become one. But painting is marvelous; it makes you happier and more patient. Af- terwards you do not have black fingers as with writing, but red and blue ones." (I,56) When Hesse began painting around 1917, he stood on the threshold of his most prolific period of creativity. This commenced with Demian and continued for more than a decade with such literary masterpieces as Klein und Wagner, Siddhartha, Kurgast up to Der Steppenwolf and beyond. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

Joseph Mileck HERMANN HESSE: LIFE, WORK, and CRITICISM (Authoritative Studies in World Literature) Fredericton, N.B.: York Press, 1984

difficult to qualify" [p. xiii]). Nevertheless, her study is useful in two respects. She knowl- edgeably draws attention to the strengths of Lowry's minor fiction, and, in digressing from her thesis, sketches the influence of specific films on Under the Volcano and October Ferry. Even though the hypothesis of Grace's The Voyage That Never Ends is unproven—and is probably unprovable—the author succeeds in opening out to fuller consideration the nature of Lowry's achievement as an artist. Joseph Mileck HERMANN HESSE: LIFE, WORK, AND CRITICISM (Authoritative Studies in World Literature) Fredericton, N.B.: York Press, 1984. Pp. 49. $6.95 Reviewed by Adrian Hsia The first reaction of a Hesse-scholar upon seeing another introductory booklet on Her mann Hesse may be the involuntary question: Is this necessary? However, this mixed feeling would soon disappear after reading a few pages. One has to admit that Joseph Mileck is a master of his craft. It is not only that his booklet left no important details untold which is, given the limited space, by itself a remarkable feat. It is the way he unfolds the biography and, especially, the works of Hermann Hesse that is truly impressive. In spite of its introductory character, even a seasoned Hesse-scholar would feel having learned something after reading Mileck's book. It is indeed a piece of scholarship which also commands the attention of the reader. One may not agree with Mileck, one may feel the urge to argue with him on certain points of interpretation, however, one would not regret having read this book. -

Hermann Hesse Sein Leben Und Sein Werk

Hermann Hesse Sein Leben und sein Werk Hugo Ball Das Vaterhaus Hermann Hesse ist geboren am 2. Juli 1877 in dem württembergischen Städtchen Calw an der Nagold. Beide Eltern waren nicht Schwaben von Geburt. Johannes Hesse, der Vater des Dichters, war seinen Papieren nach russischer Untertan, aus Weißenstein in Estland; seine Familie kam dorthin aus Dorpat und hat baltisches Gepräge; der älteste nachweisbare Familienahn kam aus Lübeck und war hanseatischer Soldat. Die Mutter des Dichters, Marie Gundert-Dubois, Tochter von Dr. Hermann Gundert-Dubois, wurde als Missionarstochter geboren in Talatscheri (Ostindien). Dem Blute und Temperamente nach kommt ihre Mutter, eine geborene Dubois, aus der Gegend von Neuchâtel und aus calvinistischer Winzerfamilie. Die von dem hanseatischen Soldaten Barthold Joachim stammenden Hesses (Vater und Sohn) zeigen einen schmalen, eher schmächtigen Typus von zartem Gliederbau; sie haben blaue, scharfe Augen und helles Haar; angespannte, habichtartige Gesichtszüge und in der Erregung spitzige, rückwärtsfliehende Ohren. Sie zeigen gefaßte Haltung, bei seelischer Berührung Schüchternheit, die sich überraschend in jähen Zorn wandeln kann; zähes, stilles, geduldig zuwartendes Wesen und Neigung zu einer edlen, ritterlichen Geselligkeit. Die Dubois (Mutter und Tochter) sind klein und schmal von Statur. Sie haben engsitzende, feurig-dunkle Augen; lebhaftes, nervöses, sanguinisches Temperament. Sie sind religiös verschwärmt und von innerer Glut verzehrt: heroische Frauen in ihren Vorsätzen und Zielen, in ihrer Hingabe und Leidenschaft; hochgemut bis zum Empfinden ihrer Überlegenheit und ihres Isoliertseins, milde aber und gütig in ihrem Werben um die ihnen Anvertrauten, worunter sie keineswegs nur die eigene Familie verstehen, sondern weit darüber hinaus die Familie der Menschenbrüder und -schwestern, die Gemeinde der gleich ihnen Opferbereiten, der Auserwählten und Heiligen. -

Culture and Violence: Psycho-Cultural Variables Involved in Homicide Across Nations

Culture and Violence: Psycho-cultural Variables Involved in Homicide across Nations Written by: Hamid Bashiriyeh Dipl. Psych. A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology, Department of Psychology; University of Koblenz-Landau Under supervision of: Professor Dr. Manfred Schmitt Dean, Department of Psychology, Koblenz-Landau University Professor Dr. Ulrich Wagner Department of Psychology, Philipps-University Marburg 2010 To my brother and true friend Iraj, whose benevolence knows no bounds. Acknowledgments For the completion of this thesis, I owe my deepest gratitude and appreciation to: - Professor Dr. Manfred Schmitt, whose supervision, continuous attention, recommendations, encouragements, and supports, made the present dissertation possible in the way it is. I have learned much more than academic knowledge from him, who was always accessible and ready to help, even at times he was submerged in lots of his professional responsibilities. - Professor Dr. Ulrich Wagner, who not only gave many valuable advices, but also offered me an opportunity to stay with him and his research team (the Group Focused Enmity) at the Dept. of Psychology in Marburg for more than six months, in a very friendly and constructive atmosphere, during which he also offered me an opportunity to receive a six-month DFG scholarship, and to have a daily access to their research facilities. I am also grateful to the following people and institutions: - Friends and colleagues I used to meet and talk to for several months at the “Group Focused Enmity” in Marburg, for their friendliness as well as inspiring ideas. - Koblenz-Landau University, for providing me with the opportunity to study in Germany - Philipps University of Marburg, Dept. -

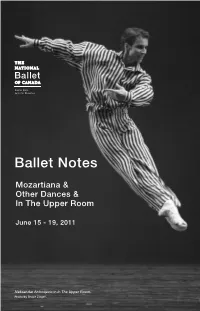

Ballet Notes

Ballet Notes Mozartiana & Other Dances & In The Upper Room June 15 - 19, 2011 Aleksandar Antonijevic in In The Upper Room. Photo by Bruce Zinger. Orchestra Violins Bassoons Benjamin BoWman Stephen Mosher, Principal Concertmaster JerrY Robinson LYnn KUo, EliZabeth GoWen, Assistant Concertmaster Contra Bassoon DominiqUe Laplante, Horns Principal Second Violin Celia Franca, C.C., Founder GarY Pattison, Principal James AYlesWorth Vincent Barbee Jennie Baccante George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Derek Conrod Csaba KocZó Scott WeVers Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Sheldon Grabke Artistic Director Executive Director Xiao Grabke Trumpets David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. NancY KershaW Richard Sandals, Principal Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk Mark Dharmaratnam Principal Conductor YakoV Lerner Rob WeYmoUth Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer JaYne Maddison Trombones Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Ron Mah DaVid Archer, Principal YOU dance / Ballet Master AYa MiYagaWa Robert FergUson WendY Rogers Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne DaVid Pell, Bass Trombone Filip TomoV Senior Ballet Master Richardson Tuba Senior Ballet Mistress Joanna ZabroWarna PaUl ZeVenhUiZen Sasha Johnson Aleksandar AntonijeVic, GUillaUme Côté*, Violas Harp Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, LUcie Parent, Principal Zdenek KonValina, Heather Ogden, Angela RUdden, Principal Sonia RodrigUeZ, Piotr StancZYk, Xiao Nan YU, Theresa RUdolph KocZó, Timpany Bridgett Zehr Assistant Principal Michael PerrY, Principal Valerie KUinka Kevin D. Bowles, Lorna Geddes, -

Compton Stage

Compton Stage 10:30 AM Bear Hill Bluegrass Bear Hill Bluegrass takes pride in performing traditional bluegrass and gospel, while adding just the right mix of classic country and comedy to please the audience and have fun. They play the familiar bluegrass, gospel and a few country songs that everyone will recognize, done in a friendly down-home manner on stage. The audience is involved with the band and the songs throughout the show. 11:10 AM T-Mart Rounders The T-Mart Rounders is an old-time trio that consists of Kevin Chesser on claw-hammer banjo, vocalist Jesse Milnes on fiddle and Becky Hill on foot percussion. They re-envision percussive dance as another instrument and arrange traditional old-time tunes using foot percussion as if it were a drum set. All three musicians have spent significant time in West Virginia learning from master elder musicians and dancers. Their goal with this project is to respect the old-time music tradition while pushing its boundaries. In addition to performing, they teach flatfooting/ clogging, fiddle, claw-hammer banjo, guitar and songwriting workshops, and call/play at square dance. 11:50 AM Hickory Bottom Band Tight three-part harmonies, solid pickin’ and lots of fun are the hallmarks of this fine Western Pennsylvania-based band. Every member has a rich musical history in a variety of genres, so the material ranges from well-known and obscure bluegrass classics to grassy versions of select radio hits from the past 40 years. No matter the music’s source, it’s “all bluegrass” from this talented bunch! 12:30 PM Davis & Elkins College Appalachian Ensemble The Davis & Elkins College Appalachian Ensemble, a student performance group led by string band director Emily Miller and dance director William Roboski, is dedicated to bringing live traditional music and dance to audiences in West Virginia and beyond. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

(SUISSE) SA Excerpt from the 2002 Balance Sheet of the “Suisse” SA Subsidiary of the Banca Popolare Di Sondrio

NOTIZIARIO Cronache Stralcio dalla Aziendali RELAZIONE DI BILANCIO 2002 della controllata BANCA POPOLARE DI SONDRIO (SUISSE) SA Excerpt from the 2002 balance sheet of the “Suisse” SA Subsidiary of the Banca Popolare di Sondrio PREFA ZIONE DEL PRESIDENTE PIERO MELA ZZINI Non per tener fede a quella che ormai è una consuetudine, bensì nell’intento di continuare a dare un paramento umanistico alla relazio- ne di bilancio, quest’anno l’attenzione è rivolta a Hermann Hesse. Gran- de spirito del passato, romanziere tedesco, naturalizzato svizzero, tra- scorse buona parte della vita nel Ticino con lo sguardo volto all’Italia che tanto amò. Di questo eminente scrittore, tormentato nell’anima, molti cele- brano il ricordo nell’anno in cui ricorrono il 125° della nascita e il 40° della morte. Anche noi quindi lo onoriamo perché in lui vi sono i connotati di assonanza tra la Svizzera e l’Italia, che caratterizzano il collegamento tra la nostra banca e la madre dall’italico suolo. Del Ticino, dove andò a vivere nel 1919, scriveva: «Quando rivedo questa regione benedetta del versante sud delle Alpi, ho sempre l’im- pressione di tornare a casa dopo un periodo di esilio, di essere final- mente di nuovo sul lato giusto delle montagne». E ancora, a Montagno- la dove le sue giornate trascorrevano serene e dove camminava con la tavolozza sotto il braccio, pronto a dipingere ogni filo, ogni albero e ogni fiore, affermava: «Produrre con la penna e col pennello è per me vino, la cui ebbrezza scalda e fa bella la vita tanto da poterla sopportare».