Historic Design Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Park and Critical Periods of Development

Cultural Landscape Report, Treatment, and Management Plan for Branch Brook Park Newark, New Jersey Volume 2: History of the Park and Critical Periods of Development Prepared for: Branch Brook Park Alliance A project of Connection-Newark 744 Broad Street, 31st Floor Newark, New Jersey 07102 Essex County Department of Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs 115 Clifton Avenue Newark, New Jersey 07104 Newark, New Jersey Cultural Landscape Report 7 November 2002 Prepared for: Branch Brook Park Alliance A project of Connection-Newark 744 Broad Street, 31st Floor Newark, New Jersey 07102 Essex County Department of Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs 115 Clifton Avenue Newark, New Jersey 07104 Prepared by: Rhodeside & Harwell, Incorporated Landscape Architecture & Planning 320 King Street, Suite 202 Alexandria, Virginia 22314 “...there is...a pleasure common, constant and universal to all town parks, and it results from the feeling of relief Professional Planning & Engineering Corporation 24 Commerce Street, Suite 1827, 18th Floor experienced by those entering them, on escaping from the Newark, New Jersey 07102-4054 cramped, confined, and controlling circumstances of the streets of the town; in other words, a sense of enlarged Arleyn Levee 51 Stella Road freedom is to all, at all times, the most certain and the Belmont, Massachusetts 02178 most valuable gratification afforded by the park.” Dr. Charles Beveridge Department of History, The American University - Olmsted, Vaux & Co. 4000 Brandywine Street, NW Landscape Architects Washington, D.C. -

Cooperbaschdissertation.Pdf

THE EVOLUTION OF VICTORIA FOUNDATION FROM 1924 TO 2003 WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON THE NEWARK YEARS FROM 1964 TO 2003 by IRENE COOPER-BASCH A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey & New Jersey Institute of Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Joint Graduate Program in Urban Systems-Education Policy Written under the direction of Dr. Alan R. Sadovnik, Rutgers University Chair and approved by _____________________________________________ Dr. Alan R. Sadovnik, Rutgers University _____________________________________________ Dr. Gabrielle Esperdy, New Jersey Institute of Technology _____________________________________________ Dr. Clement A. Price, Rutgers University _____________________________________________ Dr. Christopher J. Daggett, Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, Morristown, NJ Newark, New Jersey May, 2014 © 2014 Irene Cooper-Basch ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Evolution of Victoria Foundation From 1924 to 2003 With a Special Focus on the Newark Years From 1964 to 2003 By IRENE COOPER-BASCH Dissertation Director: Professor Alan Sadovnik This dissertation examines the history of Victoria Foundation from its inception in 1924 through 2003, with a special emphasis on its place-based urban grantmaking in Newark, New Jersey from 1964 through 2003. Insights into Victoria’s role and impact in Newark, particularly those connected to its extensive preK-12 education grantmaking, were gleaned through an analyses of the evolution of Newark, the history of education in Newark, and the history of foundations in America. Several themes emerged from the research, an examination of the archives, and 28 oral history interviews including: charity vs. philanthropy, risk-taking, scattershot grantmaking, self-reflection, issues of race, and evaluation. -

You Are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library for THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS

You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library FOR THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS Design/layout: Howard Goldstein You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library THE NEW JERSE~ TERCENTENARY 1664-1964 REPORT OF THE NEW JERSEY TERCENTENA'RY COMM,ISSION Trenton 1966 You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library STATE OF NEW .JERSEY TERCENTENARY COMMISSION D~ 1664-1964 / For Three CenturieJ People PmpoJe ProgreJs Richard J. Hughes Governor STATE HOUSE, TRENTON EXPORT 2-2131, EXTENSION 300 December 1, 1966 His Excellency Covernor Richard J. Hughes and the Honorable Members of the Senate and General Assembly of the State of New Jersey: I have the honor to transmit to you herewith the Report of the State of New Jersey Tercentenary Commission. This report describee the activities of the Commission from its establishment on June 24, 1958 to the completion of its work on December 31, 1964. It was the task of the Commission to organize a program of events that Would appropriately commemorate the three hundredth anniversary of the founding of New Jersey in 1664. I believe this report will show that the Commission effectively met its responsibility, and that the ~ercentenary obs~rvance instilled in the people of our state a renewfd spirit of pride in the New Jersey heritage. It is particularly gratifying to the Commission that the idea of the Tercentenary caught the imagination of so large a proportior. of New Jersey's citizens, inspiring many thousands of persons, young and old, to volunteer their efforts. -

The Shoppes at Edison Village Available for Lease 161 Main Street

RETAIL West Orange, NJ 950 SF - 4,500 SF The Shoppes at Edison Village Available for Lease 161 Main Street SPACE AVAILABLE SEEKING: • Restaurant/Cafe • Personal Services • Specialty Market Size Neighbors 14,016 AADT on Main Street Demographics 950 SF - 4,500 SF Rite Aid, CVS Pharmacy, The ShoppesLocated next to Thomas at Edison2018 Estimates Village Total Retail 14,800 SF Kearny Bank, Santander Bank, Edison Historical Park with Pizza Hut 161 MAIN STREET AT LAKESIDE AVENUE1 Mile 3 Miles 5 Miles Asking Rent WEST57,694 visitorsORANGE, in 2016 NEW JERSEY Upon request Comments Public transportation bus Population 32,650 260,711 709,651 MIXED USE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Phase I Residential stops on Main Street NNN Development: The Mews and Households 12,147 100,541 266,671 $6.00 Loft Units- 334 rental units Phase II Residential Median $52,724 $69,252 $73,218 Ceiling Heights Development - 250 From 15’ - 16’6” Household Townhouse units Coming Income online 2019 Daytime 9,658 79,397 281,115 Parking Population 90 free parking spaces for exclusive retail use Contact our exclusive agents: Melissa Montemuino Curtis Nassau Deborah Stone [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 201.636.7506 201.777.2302 201.636.7414 MARKET AERIAL West Orange, NJ Llewellyn Park • The �irst planned community in America • 425 acres w/ 176 prestigious estates COLUMBIA STREET Thomas Edison LIBERTY STREET 14,016 AADT Historical Park 57,694 Visitors in 2016 (no cafe) RETAIL SPACE 3.20 miles to Montclair, NJ LAKESIDE AVENUE I-280 WEST Retail Units from 950 -

Montclairneighbors JUNE 2019

A community magazine serving the residents of Montclair and Upper Montclair MontclairNeighbors JUNE 2019 The Pagliaro Family Bedazzled by Shakespeare and Creative Coding PHOTOGRAPH BY NEIL GRABOWSKY 2 MONTCLAIR NEIGHBORS Dear Residents, F YOU’VE BEEN enjoying Andrew PUBLICATION TEAM Wander’s images from his book, Stately PUBLISHER Michael Stefanelli Homes of Montclair, on our Featured CONTENT COORDINATOR Candice Horowitz Homes page, then you may be interested in Van Vleck DESIGNER Marti Golon IHouse & Gardens’ 20th Anniversary Roses to Rock Gardens Tour PHOTOGRAPHY Neil Grabowsky / Through on June 7th and 8th. This annual fundraiser will give you access The Lens Studios to some of the most unique private gardens in our area. CONTRIBUTING WRITER Scarlett Morris The tour, which is self-guided, starts at the Van Vleck Gardens where attendees pick up a guide to local homeowners’ proper- ADVERTISING ties. And if history is your thing, all those who take the tour can Contact: Michael Stefanelli also attend a special presentation at Van Vleck on Saturday, June Email: [email protected] 8th, for a presentation of the history and development of Van Phone: 973-277-7301 Vleck’s historic gardens. Did you know that the six acre prop- FEEDBACK • IDEAS • SUBMISSIONS erty was built as a private estate over 125 years ago? Or that three Have feedback, ideas or submissions? We are always happy to hear generations of the Van Vleck family lived at the estate before from you! Deadlines for submissions are the 1st of each month. it changed hands in 1993 when it was gifted to The Montclair Go to www.bestversionmedia.com and click “Submit Content.” Foundation? There’s so much more to know about this stunning You may also email your thoughts, ideas and photos to: estate. -

OPEN SPACE and RECREATION PLAN UPDATE - 2010 for the Township of West Orange County of Essex

OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN UPDATE - 2010 for the Township of West Orange County of Essex Compiled by The Land Conservancy with Township of West Orange of New Jersey Open Space, Recreation & An accredited land trust Environmental Committee June 2010 OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN UPDATE for Township of West Orange County of Essex Compiled by The Land Conservancy of Township of West Orange Open Space, Recreation and New Jersey with An accredited land trust Environmental Committee June 2010 OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN UPDATE for Township of West Orange County of Essex Produced by: The Land Conservancy of New Jersey’s Partners for Greener Communities Team: “Partnering with Communities to Preserve Natural Treasures” David Epstein, President Barbara Heskins Davis, P.P./AICP, Vice President Programs Holly Szoke, Communications Director Kenneth Fung, GIS Manager Eugene Reynolds, Project Consultant Jason Simmons, Planning Intern For further information please contact: The Land Conservancy of New Jersey Township of West Orange an accredited land trust Open Space, Recreation and Environmental Committee 19 Boonton Avenue Boonton, NJ 07005 66 Main Street (973) 541-1010 West Orange, NJ 07052 Fax: (973) 541-1131 (973) 325-4155 www.tlc-nj.org www.westorange.org Copyright © 2010 All rights reserved Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form without prior consent June 2010 Acknowledgements The Land Conservancy of New Jersey wishes to acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for their help in providing information, guidance, and materials for the West Orange Township Open Space and Recreation Plan Update. Their contributions have been instrumental in the creation of the Plan. -

Glenmont Estate, Thomas Edison National Historical Park

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2011 Glenmont Estate Thomas Edison National Historical Park Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Glenmont Estate Thomas Edison National Historical Park Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national database. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NPS Fonn 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior prop name Mountain Lakes HD National Park Service county Morris, New Jersey National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number ___)o!8 ____ Page lof28 Statement of Significance The proposed Mountain Lakes Historic District is distinguished among American residential communities in land use and landscape design. From its founding as a residential park, Mountain Lakes has integrated family living with man-made lakes, natural streams and springs, woodlands and wetlands. Dedicated parkland and undeveloped borough-owned lots contribute to spaciousness in both the proposed Mountain Lakes Historic District and the larger Borough. Throughout Mountain Lakes, forty percent of land is Borough-owned open space.1 At critical junctures in its history the Borough purchased additional undeveloped land to protect Mountain Lakes and the proposed district from intrusive development and to preserve its original design and character as a residential park. Mountain Lakes' ability to regulate its growth and maintain continuity in both landscape design and architecture has been characterized as unique in assessments of recent American city plauning.2 Its original housing stock- much of which remains today--was strongly influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement in the United States. By their location on natural rather than graded terrain, and, the use oflocal building materials, the Craftsman-influenced homes closely connect to nature and critically -

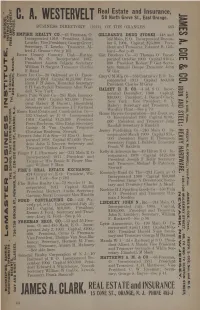

G . a . W E S T E R V E L T 10 10 K I 10

h C Z Real Estate and Insurance, -‘ 111 58 North Grove St., East Orange. S - x a G. A. W ESTERVELT ShfilU S o So BUSINESS DIRECTORY (1912) OF THE ORANGES 663 zfc“ ° EMPIRE REALTY CO.— 61 Freeman, O. GILLBARD’S DRUG STORES—448 and — zUI .III Incorporated 1910. President, Adam 562 Main, E O. Incorporated Decem ikm Leuchs; Vice President, George Greer; ber 5, 1904. Capital, $25,000. Pres Secretary, T. Leuchs; Treasurer, Al ident and Treasurer, Edward B. Gill- fred J. Grosso—See p 103 bard—See p 49 III Essex County Country Club—Hutton Gist Brothers Co—51 Thomas O Incor Park, W O. Incorporated 1887. porated October 1909 Capital $100,- CB President Austin Colgate Secretary 000 President Robert F Gist Secre i William D Sargent Treasurer Charles tary Samuel Doupe Treasurer John 1 1 F Rand W Gist 1 f f Essex Ice Co—26 Oakwood av O Incor Grey C M Mfg Co—358 Central av E O In I f * porated 1901 Capital $125,000 Pres^ corporated 1911 Capital $60,000 1 2 « ident F H Jones, Montclair Secretary i OE President Charles M Grey (DIO S H Van Syckel Treasurer Allen War- HALSEY H. B. C O .-^ 3d, S O. Incor dell, New York CVI porated December, 1900. Capital, 10 ■ Essex Pure Water Co—285 Main Incorpo > © $30,000. President, J. Bayard Clark, CD H rated 1900 Capital $25,000 Presi New York; Vice President, S. L. dent Halsey M Barrett, Bloomfield Halsey; Secretary and Treasurer, J. C 3 O Secretary and Treasurer J T Kirtland Wardley Hunt—See p 79 O O Z Essex Real Estate and Construction Co — Home Buyers Corporationfi-163 Essex av, g o Jh E U 352 Central -

Newark and Its Leading Business Men, Embracing Also, Those Of

' ^^' <$,^ e^- ''if .<f' ^^.,_.->^ . .Nf.^ -» ' . v A ° «?. * V O ' . , \^ , . , ^ * a N ^0 •^ .S' ^.^ . ..^ c^-^> .xv^^' r-J^'s" '*=-" ^. -• <^'- -^^ ,^^'' ':,:^^v- v^^^^^o^ "-^"^r.^^^ %'^^^^\.^' 'CO' -.0 0^ ,0 o^ s' •^, .y ^^ '^'^#'^^^ >^s* .^' ^' "^^ ^' OO' ,0o^ .^^" ^-^^ ^^ c-^- ,<X^" ^V^ o g^/, -^ N*^ ,0 O ,0o. -< V. ^c:^- «i^:«!A'c %> "^^ t%' .>:^^'V .s^^. '\''£'J:°. '^:' 4!i.:vf^ Z"-;^ ^N^ c"'"^* %. C^ s % % ''A V ,0 o^ v^^ ^t. ,<> '^^. ':. ,<^" 00 00^ :&:,• ' ' ^-^ ,0 o. /> ' «" ,\^^ ... .c^.>-,% *"'\^- , <^ ->^ /% = ^^ 3^ * -<^ -^ -'- > = 1:. >S 00 .^^ ^'^^ '. C- * /r .".A&., "^^ aV »^.* 0.V 'A V , ''^UA^^* ' t, '' ,9 * ' . C> V -5^.%^ .^^ "^Z". ^^^ .^ ..-. v^^- ' ..^ '^ „R ':> .<^' -^,. v-^^ 00 i^ \- \^'^ Newark is the capital of Essex County, the chief city in the State of New Jersey, the fourteenth city of the Union in point of population, the third manufac- turing city in the United States, in the aggregate im- portance of Its manufactures and one of the leading cities of the country in the extent and variety of its manufactured jjroducts. There are over 2,400 firms engaged in manufactures in this city, and over twelve hundred distinct branches of manufacture carried on within its limits. The history of Newark dates back about 225 years, when the place was first settled by a colony of sturdy New Englanders. Nearly or quite forty years after the landing of the Pilgrims on the rock- bound shores of New England, the religious differences of opinion among colonists of the Plymouth and adjacent settlements, had increased to such an ex- tent, that it was thought best by some of the leading spirits of two of the towns of the colonies, that new fields should be occupied, and fuller opportunities given for the cultiva- tion of religious thought and action. -

A Blueprint for Building Historic Preservation Into New Jersey’S Future 2002 - 2007

New Jersey Partners for Preservation: A Blueprint for Building Historic Preservation into New Jersey’s Future 2002 - 2007 James E. McGreevey Bradley M. Campbell Governor Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner P.O. Box 404 Trenton, NJ 08625-0402 September 20, 2002 Dear New Jersey Citizen: Under Governor James E. McGreevey’s smart growth initiatives, New Jersey is actively pursuing the revitalization of the state’s urban areas and encouraging the preservation of historic resources and open space. Along with economic development and community revitalization, historic preser- vation in our urban, suburban and rural areas is an essential element of promoting livable communities in New Jersey. I am pleased to present you with New Jersey Partners for Preservation: A Blueprint for Building Historic Preservation into New Jersey’s Future. This document is also known as the New Jersey Historic Preservation Plan and will be in effect from 2002 to 2007. Over the past year, the New Jersey Historic Preservation Office, Preservation New Jersey, and a host of advisors have worked diligently to complete this plan, which is intended to guide not only the New Jersey Historic Preservation Office in the Department of Environmental Protection, but also to provide direction to state, county, and local government agencies and to private organiza- tions and individuals in their efforts to protect and to preserve New Jersey’s rich and diverse history. Faced with many challenges in our efforts to preserve the state’s environment, I believe this plan, in conjunction with the New Jersey State Plan and smart growth principles, will enhance our efforts to preserve New Jersey’s important historic and archeological resources and to promote livable communities throughout the Garden State. -

Redefine, Repurpose, and Renew

MARAC SPRING 2017 • NEWARK, NEW JERSEY ADAPTABLE ARCHIVES: REDEFINE, REPURPOSE, AND RENEW • APRIL 20-22, 2017 • Newark Panorama, 1957. Charles F. Cummings New Jersey Information Center, Newark Public Library. The Local Arrangements and Program Committees welcome MARAC to Newark, New Jersey for the Spring 2017 Conference. The renaissance city of Newark offers cultural and historical sites, arts, entertainment, and fine dining that conference attendees are sure to enjoy. Our conference hotel, the Robert Treat Best Western, named for the original settler of Newark, opened in 1916 and has hosted American presidents and other dignitaries. It is conveniently located within walking distance of the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, the Newark Museum, Newark Public Library, and Rutgers University–Newark. Take advantage of the spring season and tour the spectacular Branch Brook Park cherry blossoms that bloom in April and the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, the fifth- largest cathedral in the United States. See the historic mansions in the Forest Hill section, as well as the Newark Museum and Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers- Newark. Going it on your own? Explore Newark with “Newark Walks,” an interactive and engaging pedestrian tour of the city available to you via your smartphone. We hope you brought your appetite! Newark’s Ironbound District is home to over 170 fine restaurants and eateries, many specializing in Brazilian and Iberian cuisine, and is within easy transportation of the hotel. Just like our terrific lineup of program offerings, the conference theme of “Adaptable Archives: Redefine, Repurpose, and Renew” fully expresses the dynamic, present-day Newark. Friday night’s reception will be at 15 Washington Street, a 1920s skyscraper that first served as the headquarters for the American Insurance Company and later became Rutgers’ S.I.