Glenmont Estate, Thomas Edison National Historical Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Parks Borough 0. Queens

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGH 0. QUEENS CITY OF NEW YORK FOR THE YEARS 1927 AND 1928 JAMES BUTLER Comnzissioner of Parks Printed by I?. IIUBNEH& CO. N. Y. C. PARK BOARD WALTER I<. HERRICK, Presiden,t JAMES P. BROWNE JAMES BUTLER JOSEPH P. HENNESSEY JOHN J. O'ROURKE WILLISHOLLY, Secretary JULI~SBURGEVIN, Landscafe Architect DEPARTMENT OF PARKS Borough of Queens JAMES BUTLER, Commissioner JOSEPH F. MAFERA, Secretary WILLIA&l M. BLAKE, Superintendent ANTHONY V. GRANDE, Asst. Landscape Architect EDWARD P. KING, Assistant Engineer 1,OUIS THIESEN, Forester j.AMES PASTA, Chief Clerk CITY OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGHOFQUEENS March 15, 1929. Won. JAMES J. WALKER, Mayor, City of New York, City Hall, New York. Sir-In accordance with Section 1544 of the Greater New York Charter, I herewith present the Annual Report of the Department of Parks, Borough of Queens, for the two years beginning January lst, 1927, and ending December 31st, 1928. Respectfully yours, JAMES BUTLER, Commissioner. CONTENTS Page Foreword ..................................................... 7 Engineering Section ........................................... 18 Landscape Architecture Section ................................. 38 Maintenance Section ........................................... 46 Arboricultural Section ........................................ 78 Recreational Features ......................................... 80 Receipts ...................................................... 81 Budget Appropriation ....................................... -

Strategic Policy Statement 2014 Melinda Katz

THE OFFICE OF THE QUEENS BOROUGH PRESIDENT Strategic Policy Statement 2014 Melinda Katz Queens Borough President The Borough of Queens is home to more than 2.3 million residents, representing more than 120 countries and speaking more than 135 languages1. The seamless knit that ties these distinct cultures and transforms them into shared communities is what defines the character of Queens. The Borough’s diverse population continues to steadily grow. Foreign-born residents now represent 48% of the Borough’s population2. Traditional immigrant gateways like Sunnyside, Woodside, Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, Corona, and Flushing are now communities with the highest foreign-born population in the entire city3. Immigrant and Intercultural Services The immigrant population remains largely underserved. This is primarily due to linguistic and cultural barriers. Residents with limited English proficiency now represent 28% of the Borough4, indicating a need for a wide range of social service support and language access to City services. All services should be available in multiple languages, and outreach should be improved so that culturally sensitive programming can be made available. The Borough President is actively working with the Queens General Assembly, a working group organized by the Office of the Queens Borough President, to address many of these issues. Cultural Queens is amidst a cultural transformation. The Borough is home to some of the most iconic buildings and structures in the world, including the globally recognized Unisphere and New York State Pavilion. Areas like Astoria and Long Island City are establishing themselves as major cultural hubs. In early 2014, the New York City Council designated the area surrounding Kaufman Astoria Studios as the city’s first arts district through a City Council Proclamation The areas unique mix of adaptively reused residential, commercial, and manufacturing buildings serve as a catalyst for growth in culture and the arts. -

Rochester. N. T.-For the Week Ending Saturday, September 14,1861

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Newspapers Collection 1 TWO DOLLARS A. YEAR.] "PROGRESS AND IMPROVEMENT. [STNGKL.E NO. B^OTJR CENTS. VOL XH. NO. 37.} ROCHESTER. N. T.-FOR THE WEEK ENDING SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 14,1861. {WHOLE NO. 609. in June for the first time in the second year. The mitted to grow. All weeds that have commenced RETURN-TABLE APPLE PAEEE. MOORE'S RURAL NEW-YORKER, best plan is to turn on your stock when the seed flowering should be collected together in a pile, dried AN ORIGINAL WEEKLY. ripens in June. Graze off the grass, then allow the and burned. If gathered before flowers are formed AMONG all the inventions AGBICUITURAL, LUEKARY ANB FAMILY JOURNAL. fall growth, and graze all winter, taking care never to they may be placed upon the compost heap and for paring apples which have feed the grass closely at any time.1' mixed with fermenting manures. CONDUCTED BY D. D. T. MOORE, come under our observation The number of seeds produced by our common With an Abie Corps of Assistants and Contributors, Canada Thistles. of late years, the "Return- weeds is really astonishing to those who have no Table Apple Parer," recent- CHAS. D. BKASDON1, Western Corresponding Editor. SOME years since, in our investigations among studied the matter. A good plant of dock will ripen ly patented lay WHITTEMORE the flowers and weeds, we found what was new to us from twelve to fifteen thousand seeds, burdock over BROTHERS, Worcester, Mass., — a Canada thistle with white flowers. In the twenty thousand, and pig-weed some ten thousand. -

A Guide to Flushing in Queens

A GUIDE TO FLUSHING IN QUEENS Ethnic diversity is the hallmark of New York City, and nowhere is this diversity more evident than in Flushing, Queens. Founded in 1645, Flushing, then called Vlissingen, was granted a charter by the Dutch West India Company and became a part of New Netherlands. Subsequent periods of immigration resulted in colonization by English settlers, and more recently by settlers from Taiwan, mainland China, Japan and Korea. The result is an ethnic medley to be savored in its streets, shops, restaurants and cultural institutions. Where is Flushing? Located on western Long Island, Queens is one of the five boroughs of New York City. Established in 1683, it was named for the queen consort, Catherine of Braganza, wife of Charles II. The borough of Queens is divided into four “towns,” Jamaica, Long Island City, Flushing, and Far Rockaway. Unlike the other boroughs, mail in Queens is addressed to the applicable town rather than “Queens, N. Y.” About Flushing The first It’s Easy to Get to Flushing settlers in Flushing were, From either Times Square, or Grand Central Station, oddly enough, take the Number 7 train to the last stop and you will a group of be in the heart of Flushing. Englishmen who arrived in 1645 from Vlissingen in Holland under a patent from the Dutch West Indies Company. Subsequently an influx of Quakers from the English colonial settlements in Massachusetts took place in 1657. With the arrival of the Quakers, Governor Peter Stuyvesant, known as Peg Leg Pete, issued an edict banning all forms of worship other than Dutch Reformed, despite the guaranty of freedom of worship contained in the official Dutch charter. -

History of the Park and Critical Periods of Development

Cultural Landscape Report, Treatment, and Management Plan for Branch Brook Park Newark, New Jersey Volume 2: History of the Park and Critical Periods of Development Prepared for: Branch Brook Park Alliance A project of Connection-Newark 744 Broad Street, 31st Floor Newark, New Jersey 07102 Essex County Department of Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs 115 Clifton Avenue Newark, New Jersey 07104 Newark, New Jersey Cultural Landscape Report 7 November 2002 Prepared for: Branch Brook Park Alliance A project of Connection-Newark 744 Broad Street, 31st Floor Newark, New Jersey 07102 Essex County Department of Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs 115 Clifton Avenue Newark, New Jersey 07104 Prepared by: Rhodeside & Harwell, Incorporated Landscape Architecture & Planning 320 King Street, Suite 202 Alexandria, Virginia 22314 “...there is...a pleasure common, constant and universal to all town parks, and it results from the feeling of relief Professional Planning & Engineering Corporation 24 Commerce Street, Suite 1827, 18th Floor experienced by those entering them, on escaping from the Newark, New Jersey 07102-4054 cramped, confined, and controlling circumstances of the streets of the town; in other words, a sense of enlarged Arleyn Levee 51 Stella Road freedom is to all, at all times, the most certain and the Belmont, Massachusetts 02178 most valuable gratification afforded by the park.” Dr. Charles Beveridge Department of History, The American University - Olmsted, Vaux & Co. 4000 Brandywine Street, NW Landscape Architects Washington, D.C. -

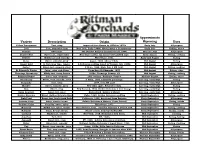

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

Senior Resource Guide

New York State Assemblywoman Nily Rozic Assembly District 25 Senior Resource Guide OFFICE OF NEW YORK STATE ASSEMBLYWOMAN NILY ROZIC 25TH DISTRICT Dear Neighbor, I am pleased to present my guide for seniors, a collection of resources and information. There are a range of services available for seniors, their families and caregivers. Enclosed you will find information on senior centers, health organizations, social services and more. My office is committed to ensuring seniors are able to age in their communities with the services they need. This guide is a useful starting point and one of many steps my office is taking to ensure this happens. As always, I encourage you to contact me with any questions or concerns at 718-820-0241 or [email protected]. I look forward to seeing you soon! Sincerely, Nily Rozic DISTRICT OFFICE 159-16 Union Turnpike, Flushing, New York 11366 • 718-820-0241 • FAX: 718-820-0414 ALBANY OFFICE Legislative Office Building, Room 547, Albany, New York 12248 • 518-455-5172 • FAX: 518-455-5479 EMAIL [email protected] This guide has been made as accurate as possible at the time of printing. Please be advised that organizations, programs, and contact information are subject to change. Please feel free to contact my office at if you find information in this guide that has changed, or if there are additional resources that should be included in the next edition. District Office 159-16 Union Turnpike, Flushing, NY 11366 718-820-0241 E-mail [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS (1) IMPORTANT NUMBERS .............................. 6 (2) GOVERNMENT AGENCIES ........................... -

20 City Council District Profiles

QUEENS CITY Flushing, East Flushing, Murray Hill, COUNCIL 2009 DISTRICT 20 Auburndale, Queensboro Hill Parks are an essential city service. They are the barometers of our city. From Flatbush to Flushing and Morrisania to Midtown, parks are the front and backyards of all New Yorkers. Well-maintained and designed parks offer recreation and solace, improve property values, reduce crime, and contribute to healthy communities. SHOWCASE : Kissena Park The Daffodil Project, a partnership between New Yorkers for Parks and the NYC Parks Department, was cre- ated as a citywide beautification project and living memorial to September 11. Each year, thanks to the generous donation of B&K Flowerbulbs, the two groups distribute hundreds of thousands of free daffodil bulbs for volun- teers and community groups to plant in New York City’s parks and open spaces. In 2008 the Friends of Kissena Park, a Margaret Carman Green, Flushing neighborhood conservancy group, The Bloomberg Administration’s physical barriers or crime. As a result, planted more than 1,000 daffodils in Kissena Park. Visit www.ny4p. PlaNYC is the first-ever effort to studies show significant increases in org for more information on sustainably address the many infra- nearby real estate values. Greenways The Daffodil Project. structure needs of New York City, are expanding waterfront access including parks. With targets set for while creating safer routes for cyclists stormwater management, air quality and pedestrians, and the new initia- and more, the City is working to tive to reclaim streets for public use update infrastructure for a growing brings fresh vibrancy to the city. -

Cooperbaschdissertation.Pdf

THE EVOLUTION OF VICTORIA FOUNDATION FROM 1924 TO 2003 WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON THE NEWARK YEARS FROM 1964 TO 2003 by IRENE COOPER-BASCH A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey & New Jersey Institute of Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Joint Graduate Program in Urban Systems-Education Policy Written under the direction of Dr. Alan R. Sadovnik, Rutgers University Chair and approved by _____________________________________________ Dr. Alan R. Sadovnik, Rutgers University _____________________________________________ Dr. Gabrielle Esperdy, New Jersey Institute of Technology _____________________________________________ Dr. Clement A. Price, Rutgers University _____________________________________________ Dr. Christopher J. Daggett, Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, Morristown, NJ Newark, New Jersey May, 2014 © 2014 Irene Cooper-Basch ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Evolution of Victoria Foundation From 1924 to 2003 With a Special Focus on the Newark Years From 1964 to 2003 By IRENE COOPER-BASCH Dissertation Director: Professor Alan Sadovnik This dissertation examines the history of Victoria Foundation from its inception in 1924 through 2003, with a special emphasis on its place-based urban grantmaking in Newark, New Jersey from 1964 through 2003. Insights into Victoria’s role and impact in Newark, particularly those connected to its extensive preK-12 education grantmaking, were gleaned through an analyses of the evolution of Newark, the history of education in Newark, and the history of foundations in America. Several themes emerged from the research, an examination of the archives, and 28 oral history interviews including: charity vs. philanthropy, risk-taking, scattershot grantmaking, self-reflection, issues of race, and evaluation. -

You Are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library for THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS

You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library FOR THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS Design/layout: Howard Goldstein You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library THE NEW JERSE~ TERCENTENARY 1664-1964 REPORT OF THE NEW JERSEY TERCENTENA'RY COMM,ISSION Trenton 1966 You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library STATE OF NEW .JERSEY TERCENTENARY COMMISSION D~ 1664-1964 / For Three CenturieJ People PmpoJe ProgreJs Richard J. Hughes Governor STATE HOUSE, TRENTON EXPORT 2-2131, EXTENSION 300 December 1, 1966 His Excellency Covernor Richard J. Hughes and the Honorable Members of the Senate and General Assembly of the State of New Jersey: I have the honor to transmit to you herewith the Report of the State of New Jersey Tercentenary Commission. This report describee the activities of the Commission from its establishment on June 24, 1958 to the completion of its work on December 31, 1964. It was the task of the Commission to organize a program of events that Would appropriately commemorate the three hundredth anniversary of the founding of New Jersey in 1664. I believe this report will show that the Commission effectively met its responsibility, and that the ~ercentenary obs~rvance instilled in the people of our state a renewfd spirit of pride in the New Jersey heritage. It is particularly gratifying to the Commission that the idea of the Tercentenary caught the imagination of so large a proportior. of New Jersey's citizens, inspiring many thousands of persons, young and old, to volunteer their efforts. -

The Invention of the Electric Light

The Invention of the Electric Light B. J. G. van der Kooij This case study is part of the research work in preparation for a doctorate-dissertation to be obtained from the University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands (www.tudelft.nl). It is one of a series of case studies about “Innovation” under the title “The Invention Series”. About the text—This is a scholarly case study describing the historic developments that resulted in the steam engine. It is based on a large number of historic and contemporary sources. As we did not conduct any research into primary sources, we made use of the efforts of numerous others by citing them quite extensively to preserve the original character of their contributions. Where possible we identified the individual authors of the citations. As some are not identifiable, we identified the source of the text. Facts that are considered to be of a general character in the public domain are not cited. About the pictures—Many of the pictures used in this case study were found at websites accessed through the Internet. Where possible they were traced to their origins, which, when found, were indicated as the source. As most are out of copyright, we feel that the fair use we make of the pictures to illustrate the scholarly case is not an infringement of copyright. Copyright © 2015 B. J. G. van der Kooij Cover art is a line drawing of Edison’s incandescent lamp (US Patent № 223.898) and Jablochkoff’s arc lamp (US Patent № 190.864) (courtesy USPTO). Version 1.1 (April 2015) All rights reserved. -

The Shoppes at Edison Village Available for Lease 161 Main Street

RETAIL West Orange, NJ 950 SF - 4,500 SF The Shoppes at Edison Village Available for Lease 161 Main Street SPACE AVAILABLE SEEKING: • Restaurant/Cafe • Personal Services • Specialty Market Size Neighbors 14,016 AADT on Main Street Demographics 950 SF - 4,500 SF Rite Aid, CVS Pharmacy, The ShoppesLocated next to Thomas at Edison2018 Estimates Village Total Retail 14,800 SF Kearny Bank, Santander Bank, Edison Historical Park with Pizza Hut 161 MAIN STREET AT LAKESIDE AVENUE1 Mile 3 Miles 5 Miles Asking Rent WEST57,694 visitorsORANGE, in 2016 NEW JERSEY Upon request Comments Public transportation bus Population 32,650 260,711 709,651 MIXED USE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Phase I Residential stops on Main Street NNN Development: The Mews and Households 12,147 100,541 266,671 $6.00 Loft Units- 334 rental units Phase II Residential Median $52,724 $69,252 $73,218 Ceiling Heights Development - 250 From 15’ - 16’6” Household Townhouse units Coming Income online 2019 Daytime 9,658 79,397 281,115 Parking Population 90 free parking spaces for exclusive retail use Contact our exclusive agents: Melissa Montemuino Curtis Nassau Deborah Stone [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 201.636.7506 201.777.2302 201.636.7414 MARKET AERIAL West Orange, NJ Llewellyn Park • The �irst planned community in America • 425 acres w/ 176 prestigious estates COLUMBIA STREET Thomas Edison LIBERTY STREET 14,016 AADT Historical Park 57,694 Visitors in 2016 (no cafe) RETAIL SPACE 3.20 miles to Montclair, NJ LAKESIDE AVENUE I-280 WEST Retail Units from 950