沙漠研究25-3, 237-240

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T/R 1 1-O'rin 2 2-O'rin 3 3-O'rin 4 5 6 7

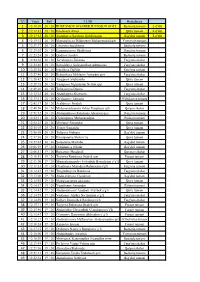

T/r Vaqti Ball F.I.SH Hududingiz 1 12:10:05 20 / 20 RUSTAMOV OG'ABEK ILYOSJON OG'LI Beshariq tumani 1-o'rin 2 12:12:43 20 / 20 Ibrohimov Axror Quva tumani 2-o'rin 3 12:17:33 20 / 20 Xoshimova Sarvinoz Qobiljon qizi Bag'dod tumani 3-o'rin 4 12:19:12 20 / 20 Mamataliyeva Dildoraxon Muhammadali qizi Yozyovon tumani 5 12:21:17 20 / 20 Umarova Sug'diyona Beshariq tumani 6 12:23:02 20 / 20 Egamnazarova Shahloxon Dang'ara tumani 7 12:23:24 20 / 20 Qodirov Javohir Beshariq tumani 8 12:24:38 20 / 20 Jo'raboyeva Zebiniso Farg'ona shahar 9 12:24:46 20 / 20 Sotvoldieva Guloyim Rustambekovna Farg'ona shahar 10 12:25:54 20 / 20 Ismoilova Gullola Farg'ona tumani 11 12:27:46 20 / 20 Bektosheva Mohlaroy Anvarjon qizi Farg'ona shahar 12 12:28:42 20 / 20 Turģunov Shukurullo Quva tumani 13 12:29:18 20 / 20 Yusupova Niginabonu Ne'mat qizi Quva tumani 14 12:29:20 20 / 20 Tohirjonova Diyora Farg'ona shahar 15 12:32:35 20 / 20 Abdullayeva Shaxnoza Farg'ona shahar 16 12:33:31 20 / 20 Qo'chqorov Jahongir O'zbekiston tumani 17 12:43:17 20 / 20 Arabboyev Jòrabek Quva tumani 18 12:48:56 20 / 20 Muhammadjonova Odina Yoqubjon qizi Qo'qon shahar 19 12:51:32 20 / 20 Abdumalikova Ruhshona Abrorjon qizi Dang'ara tumani 20 12:52:11 20 / 20 G'ulomjonov Muhammadjon Rishton tumani 21 12:52:25 20 / 20 Mirzayev Samandar Quva tumani 22 12:55:03 20 / 20 Toirov Samandar Quva tumani 23 12:56:05 20 / 20 Tolipova Gulmira Bag'dod tumani 24 12:57:36 20 / 20 Ikromjonova Shohroʻza Quva tumani 25 12:57:45 20 / 20 Solijonova Marxabo Bag'dod tumani 26 12:06:19 19 / 20 Ochildinova Nilufar -

Water Productivity at Demonstration Plots and Farms

PROJECT Water Productivity Improvement on Plot Level REPORT Water productivity at demonstration plots and farms (Inception phase: April2008 – February2009) Project director SIC ICWC Victor Dukhovny Project director IWMI Herath Manthrithilake Regional project manager Shukhrat Mukhamedzhanov Tashkent 2009 EXECUTORS I. Project regional group 1. Regional project manager Sh.Sh. Mukhamedzhanov 2. Agronomy consultant S.A. Nerozin 3. Hydraulic engineering consultant Sh.R.Hamdamov 4. Regional technicians I.I. Ruziev G.U. Umirzakov II. Regional executors 5. Andizhan region S.Ergashev, A.Ahunov, I.Kushmakov 6. Fergana region M.Mirzaliev, H.Umarov, A.Rahmatillaev, I.Ganiev, R.Begmatov 7. Sogd region Z.Umarkulov, I.Halimov, M.Saidhodzhiev 8. Osh region S.A.Alybaev, K.Avazov, Z.Kamilov 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………... 2. Water productivity in Andizhan region…………………………………………. 3. Water productivity in Fergana region ………………………………………….. 4. Water productivity in Osh region ……………………………………………… 5. Water productivity in Sogd region……………………………………………… 6. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………. 3 1. Introduction Interaction of all the levels of water use from the main canal to a field is very important at achieving productive water use. Reforms of water sector are aimed at ensuring water user’s (farmer) demand and fulfilling the crop physiological requirements. Improving of irrigation systems, their management and operation from river basins, large canals to the inter-farm level should be done taking into account a real conditions and requirements of the water consumer. The systems and structures should correspond to the real needs taking into account the own power and to be aimed at reception of the maximum water productivity and profit of the farmer. We have to notice that this project (WPI-PL) has emerged on the basis of IWRM-Fergana project; its main objective is searching the organizational forms of interrelation of science and practice concerning the organizing, introducing and disseminating the best practices of irrigated agriculture. -

T/R Vaqti Ball F.I.SH Hududingiz Maktab 1 12:06:41 9 / 10 Rahimova Mushtariy Sherzodbek Qizi Farg'ona Shahar 1-Maktab 1-O'rin 2

T/r Vaqti Ball F.I.SH Hududingiz Maktab 1 12:06:41 9 / 10 Rahimova Mushtariy Sherzodbek qizi Farg'ona shahar 1-maktab 1-o'rin 2 12:09:56 9 / 10 Jabborov Anvarjon Yozyovon tumani 15 maktab 2-o'rin 3 12:10:39 9 / 10 Журабоев Шохдил So'x tumani 18 3-o'rin 4 12:14:00 9 / 10 Abdullajonova Madina Farg'ona shahar 6 5 12:14:21 9 / 10 Abdullajonova Madina Farg'ona shahar 6 6 12:15:45 9 / 10 Зарафшонова Умида Yozyovon tumani 30 7 12:15:52 9 / 10 Asqarova Nozima Toshloq tumani 15-maktab 8 12:18:29 9 / 10 Madolimova Dilnura Toshloq tumani 30 9 12:18:45 9 / 10 Ro'ziqov islom Farg'ona shahar 6 10 12:20:06 9 / 10 Комилжонов шукурулло Yozyovon tumani 30 11 12:22:43 9 / 10 Маьмиржонова Нозима Yozyovon tumani 30 12 12:25:19 9 / 10 MadaminovMuxammadaxror25 Toshloq tumani 25 13 12:28:18 9 / 10 USMONOV Farg'ona tumani 15 14 12:01:34 8 / 10 MADAMINOVA MASHHURA Farg'ona shahar 4 15 12:01:36 8 / 10 7-maktab Farg'ona shahar 7 16 12:01:36 8 / 10 Xabibullayev Abdullo 2-IDUM Toshloq tumani 2-IDUM 17 12:01:37 8 / 10 Sodiqova Sevara Farg'ona shahar 41-maktab 18 12:01:53 8 / 10 Nurmuhammedova Diyorabonu Farg'ona tumani 52 19 12:01:58 8 / 10 Abdullayeva Marhonoy Farg'ona shahar 20-m 20 12:02:00 8 / 10 Bahodirova Sarvinoz Bag'dod tumani 11-maktab 21 12:02:05 8 / 10 Кобилжонов Одилжон Farg'ona tumani 19 мактаб 22 12:02:18 8 / 10 Muhammadmusayev Abubakr Rishton tumani 59 23 12:02:19 8 / 10 Турсуналиев Сардор Quvasoy shahar 22 24 12:02:20 8 / 10 Rafiqov abdulxamid 21maktab Beshariq tumani 21 maktab 25 12:02:23 8 / 10 Yaxyoyeva Muslimaxon Farg'ona shahar 5 26 12:02:23 8 / -

Ada Metan Nukus" Мчж 2016-07-23

Нефть, газ (шу жумладан, сиқилган табиий ва суюлтирилган углеводород газини) ҳамда газ конденсатини қазиб чиқариш, қайта ишлаш ва сотиш учун лицензия тақдим этилган юридик шахслар тўғрисида МАЪЛУМОТ Лицензия серияси Лицензия берилган Т/Р Лицензия эгасининг тўлиқ номи ва рақами сана 1 АВ 1557 "ADA METAN NUKUS" МЧЖ 2016-07-23 2 АВ 1913 “QARAQALPAQ AVTO SERVIS” МЧЖ 2016-03-18 3 АА 0234 "Гулайым" МЧЖ 2018-11-14 4 АС 1211 "KOR-UNG INVESTMENT" МЧЖ 2020-12-07 5 АВ 2938 "Автогаз Эко Метан" МЧЖ 2016-07-23 6 АВ 3209 "Хожели Пропан Газ" МЧЖ 2017-06-04 7 АВ 3346 "BOLAT KAPITAL SERVIS" МЧЖ 2017-10-25 8 АА 0228 "Гулнора Газ Сервис" МЧЖ 2018-11-14 9 АА 0338 "Miymandos Nukus" МЧЖ 2019-01-30 10 АС 0082 "IDEAL GAZ" МЧЖ 2019-05-06 11 АС 1344 "АКК МЕTAN OIL" МЧЖ 2021-01-22 12 АС 0268 KARAKALPAK PROPAN NOKIS МЧЖ 2019-08-26 13 АС 0618 "Гулайым-2" МЧЖ 2020-02-07 14 АС 0634 "Нукус Метан Транс сервис" МЧЖ 2020-02-07 15 АС 0958 "MAX SERVICE GAZ" МЧЖ 2020-08-12 16 АС 1018 "JAYXUN MILANA" МЧЖ 2020-09-21 17 АС 1454 "MAMIR XAZINASI" МЧЖ 2021-03-19 18 АС 1066 "NAZLIMXAN ARZAYIM" МЧЖ 2020-10-23 19 АС 1204 "XUSHNUDBEK-XURSHIDBEK" МЧЖ 2020-12-07 20 АС 0322 "Дарбент Хужели" МЧЖ 2019-09-20 21 АВ 3036 "XOJELI METAN SERVIS" МЧЖ 2016-12-30 "KUNGRAD METAN TRADE" МЧЖ 22 АВ 3270 2017-07-14 "Каракалпак Авто Кемпинг" МЧЖ 23 АВ 3292 2017-07-14 "Канликул Иншоат тамирлаш" МЧЖ 24 АВ 3337 2017-09-12 "ANTAKIA GOLD" МЧЖ 25 АВ 0092 2018-08-03 "IRODA TAXIATASH" МЧЖ 26 АС 0276 2019-08-26 "Нукус Электрон Жихозлари" МЧЖ 27 АВ 1912 2018-03-13 "Шоманай Метан" МЧЖ 28 АА 0261 2019-11-29 Лицензия -

Download This Article in PDF Format

E3S Web of Conferences 258, 06068 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202125806068 UESF-2021 Possibilities of organizing agro-touristic routes in the Fergana Valley, Uzbekistan Shokhsanam Yakubjonova1,*, Ziyoda Amanboeva1, and Gulnaz Saparova2 1Tashkent State Pedagogical University, Bunyodkor Road, 27, Tashkent, 100183, Uzbekistan 2Tashkent State Agrarian University, University str., 2, Tashkent province, 100140, Uzbekistan Abstract. The Fergana Valley, which is rich in nature and is known for its temperate climate, is characterized by the fact that it combines many aspects of the country's agritourism. As a result of our research, we have identified the Fergana Valley as a separate agro-tourist area. The region is rich in high mountains, medium mountains, low mountains (hills), central desert plains, irrigated (anthropogenic) plains, and a wide range of agrotouristic potential and opportunities. The creation and development of new tourist destinations is great importance to increase the economic potential of the country. This article describes the possibilities of agrotourism of the Fergana valley. The purpose of the work is an identification of agro-tours and organization of agro-tourist routes on the basis of the analysis of agro-tourism potential and opportunities of Fergana agro-tourist region. 1 Introduction New prospects for tourism are opening up in our country, and large-scale projects are being implemented in various directions. In particular, in recent years, new types of tourism such as ecotourism, agrotourism, mountaineering, rafting, geotourism, educational tourism, medical tourism are gaining popularity [1-4]. Today, it is important to develop the types of tourism in the regions by studying their tourism potential [1, 3]. -

Second Crop Production in the Ferghana Valley, Uzbekistan

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265550854 Beyond the state order? Second crop production in the Ferghana Valley, Uzbekistan Article · March 2014 DOI: 10.7564/14-IJWG58 CITATIONS READS 4 107 4 authors, including: Kai Wegerich Jusipbek Kazbekov Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg Consultative Group on International Agr… 104 PUBLICATIONS 536 CITATIONS 40 PUBLICATIONS 238 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Kai Wegerich letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 16 September 2016 International Journal of Water Governance 2 (2014) 83–104 83 DOI: 10.7564/14-IJWG58 Beyond the state order? Second crop production in the Ferghana Valley, Uzbekistan Alexander Platonova, Kai Wegerichb,*, Jusipbek Kazbekova and Firdavs Kabilova aInternational Water Management Institute – Central Asia and the Caucasus office. Apt.121, House 6, Osiyo Street, Tashkent 100000, Uzbekistan. Phone: + 998-71-2370445; Fax: + 998-71-2370317 E-mails: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] bInternational Water Management Institute – East Africa and Nile Basin office. IWMI c/o ILRI, PO Box 5689, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Phone: +251 11 617 2199; Fax: +251 11 617 2001 E-mail: [email protected] After independence in 1991, Uzbekistan introduced a policy on food security and conse- quently reduced the irrigated area allocated to cotton and increased the area of winter wheat. Shifting to winter wheat allowed farmers to grow a second crop outside the state-order system. The second crops are the most profitable and therefore farmers tried to maximize the area grown to this second crop. -

Alkogolli Mahsulotlar Bilan Chakana Savdo Qilish Huquqini Beradigan Ruxsat Guvohnomasiga Ega Bo'lgan Xo'jalik Yurituvchi Subektlar

Alkogolli mahsulotlar bilan chakana savdo qilish huquqini beradigan ruxsat guvohnomasiga ega bo'lgan xo'jalik yurituvchi subektlar Amal qilish muddati № STIR Korxona nomi Faoliyat turi Dan Gacha Alkogolli mahsulotlar bilan chakana savdo qilish 1 305236176 SHAHMARDAN 12.11.2018 12.11.2020 huquqini beradigan ruxsat guvohnomasi ОБЩЕСТВО С ОГРАНИЧЕННОЙ Alkogolli mahsulotlar bilan chakana savdo qilish 2 204173212 14.12.2018 31.12.2023 ОТВЕТСТВЕННОСТЬЮ "OSIYO SHAROB SAVDO huquqini beradigan ruxsat guvohnomasi Alkogolli mahsulotlar bilan chakana savdo qilish 3 304903748 BACHQIR TANTANA 25.12.2018 31.12.2023 huquqini beradigan ruxsat guvohnomasi Alkogolli mahsulotlar bilan chakana savdo qilish 4 301531367 PESHKU TUMAN SHAROB SAVDO BAZA 28.12.2018 27.12.2020 huquqini beradigan ruxsat guvohnomasi ОБЩЕСТВО С ОГРАНИЧЕННОЙ Alkogolli mahsulotlar bilan chakana savdo qilish 5 204173212 17.01.2019 17.01.2024 ОТВЕТСТВЕННОСТЬЮ "OSIYO SHAROB SAVDO huquqini beradigan ruxsat guvohnomasi Alkogolli mahsulotlar bilan chakana savdo qilish 6 301688528 Azim Turon Savdo 23.01.2019 31.12.2021 huquqini beradigan ruxsat guvohnomasi Alkogolli mahsulotlar bilan chakana savdo qilish 7 205691074 MALIK SHAROB SAVDO MCHJ 04.02.2019 31.03.2020 huquqini beradigan ruxsat guvohnomasi ОБЩЕСТВО С ОГРАНИЧЕННОЙ 8 204766193 Alkogolli mahsulotlar bilan chakana savdo qilish 07.03.2019 07.03.2020 ОТВЕТСТВЕННОСТЬЮ "CHIRCHIQSHAROBSAVD huquqini beradigan ruxsat guvohnomasi Alkogolli mahsulotlar bilan chakana savdo qilish 9 302978466 ROYAL ABSOLUTE 20.02.2019 01.03.2020 huquqini beradigan -

The Importance of the Geographical Location of the Fergana Valley In

International Journal of Engineering and Information Systems (IJEAIS) ISSN: 2643-640X Vol. 4 Issue 11, November - 2020, Pages: 219-222 The Importance of the Geographical Location of the Fergana Valley in the Study of Rare Plants Foziljonov Shukrullo Fayzullo ugli Student of Andijan state university (ASU) [email protected] Abstract: Most of the rare plants in the Fergana Valley are endemic to this area, meaning they do not grow elsewhere. Therefore, the Fergana Valley is an area with units and environmental conditions that need to be studied. This article gives you a brief overview on rare species in the area. Key words: Fergana, flora, geographical location, mountain ranges. Introduction. The Fergana Valley, the Fergana Valley, is a valley between the mountains of Central Asia, one of the largest mountain ranges in Central Asia. It is bounded on the north by the Tianshan Mountains and on the south by the Gissar Mountains. Mainly in Uzbekistan, partly in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. It is triangular in shape, extending to the northern slopes of the Turkestan and Olay ridges, and is bounded on the northwest by the Qurama and Chatkal ridges, and on the northeast by the Fergana ridge. In the west, a narrow corridor (8–10 km wide) is connected to the Tashkent-Mirzachul basin through the Khojand Gate. Uz. 300 km, width 60–120 km, widest area 170 km, area 22 thousand km. Its height is 330 m in the west and 1000 m in the east. Its general structure is elliptical. It expands from west to east. The surface of the Fergana Valley is filled with Quaternary alluvial and proluvial-alluvial sediments. -

Uzunmo'ylov Qo'ng'izlar

ACADEMIC RESEARCH IN EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES VOLUME 2 | ISSUE 6 | 2021 ISSN: 2181-1385 Scientific Journal Impact Factor (SJIF) 2021: 5.723 DOI: 10.24411/2181-1385-2021-01093 UZUNMO‘YLOV QO‘NG‘IZLAR (COLEOPTERA: CERAMBYCIDAE) FAUNASIGA DOIR YANGI MA`LUMOTLAR Akmaljon Akbarovich Ma'rupov Farg‘ona davlat universiteti tadqiqotchisi Islomjon Ilxomjonovich Zokirov Farg‘ona davlat universiteti dotsenti, biologiya fanlari doktori ANNOTATSIYA Farg‘ona vodiysida uzunmo‘ylov qo‘ng‘izlarining 6 ta kenja oilasiga mansub 30 ta avlod 81 turi uchraydi. Prioninae, Cerambycinae va Lamiinae kenja oilalarining 13 avlodga mansub 21 (25,9%) turi Farg‘ona vodiysi hududida ilk marta qayd etildi. Shulardan 1 kenja turi O‘zbekiston faunasi uchun endemik sanaladi. Aniqlangan mo‘ylovdorlar vodiy hududida 36 turdagi mevali hamda manzarali daraxt va butalarda oziqlanadi. Qo‘ng‘izlar trofik ixtisoslashuviga ko‘ra 8 turi polifag, 9 turi oligofag va 7 turi monofaglardir. 7 tur faunada dominantlik qiladi. Kalit so‘zlarlar: Monofag, polifag, antropogen, monotipik, qayrag‘och, Apatophyseinae, biogeotsenoz, acer, Prioninae. ABSTRACT In the Fergana Valley, there are 81 species belonging to 30 genera from 6 subfamilies of long-horned beetles. For the first time, 21 (25.9%) species were recorded in the Fergana Valley, belonging to 13 genera of the subfamilies Prioninae, Cerambycinae and Lamiinae. Of the subfamilies listed above, 1 subspecies is considered endemic for the fauna of Uzbekistan. The barbel beetles identified on the territory of the valleys feed on 36 species of fruit and ornamental trees and shrubs. By trophic specialization of beetles, polyphages - 8 species, oligophages - 9, monophages - 7. Of the identified insects, 7 species are recognized as dominant in this fauna. -

Iste'mol Bozor

FARG’ONA VILOYATI STATISTIKA BOSHQARMASI FARG‘ONA VILOYATINING CHAKANA SAVDO TOVAR AYLANMASI (2020-yil yanvar-mart, dastlabki ma’lumot) Farg‘ona viloyati bo‘yicha joriy yilning yanvar-mart oyilarida chakana savdo tovar aylanmasi 3 146,1 mlrd. so`mni tashkil etib, 2019-yilning yanvar-mart oylariga nisbatan 2,4 % ga o‘sdi. Shu jumladan, yirik korxonalarning tovar aylanmasi 367,2 mlrd. so‘mni (o‘sish sur’ati 101,6 %), kichik biznes va xususiy tadbirkorlik subyektlarining tovar aylanmasi 2 778,9 mlrd. so‘mni (o‘sish sur’ati 1 02,9 %), shundan uyushmagan savdo tovar aylanmasi 261,1 mlrd. so‘mni (2019-yil yanvar-mart oylariga nisbatan o‘sish sur`ati 101,0 %) tashkil etdi. Hududlar kesimida chakana savdo tovar aylanmasi hajmi (mlrd. so‘m) 2019-yilning shu davriga nisbatan viloyatning barcha hududlarida chakana savdo tovar aylanmasining o‘sish sur’atilari kuzatilib, nisbatan yuqori o‘sish sur’atlari, Marg‘ilon (104,3 %), Farg‘ona (104,2 %), Qo‘qon (103,2 %), shaharlarida, shuningdek, Quva (101,2 %), Qo‘shtepa (100,1 %), va Uchko‘prik (100,1 %) tumanlarida qayd etildi. 1 FARG’ONA VILOYATI STATISTIKA BOSHQARMASI Chakana savdo tovar aylanmasining o‘sish sur’atlari, (%) da Chakana savdo tovar aylanmasi tarkibida yirik korxonalarning tovar aylanmasi hajmi, 2019-yil yanvar-mart oylariga nisbatan 1,6 % ga kamaygan va 367,2 mlrd. so‘mni tashkil qildi. Bu esa umumiy savdo hajmining 11,7 % ulushiga to‘g`ri keladi. Kichik biznes va xususiy tadbirkorlik subyektlarining chakana savdo tovar aylanmasi hajmi statistik hisob-kitoblarga ko‘ra, 2 778,9 mlrd. so`mni tashkil etib, 2019-yilning yanvar- mart oylariga nisbatan 2,9 % ga o‘sdi. -

50022-002: Affordable Rural Housing Program

Environmental Monitoring Report # Annual Safeguard Monitoring Report February 2019 UZB: Affordable Rural Housing Program Prepared by Rustam Saparov (Management and Monitoring Unit) for the Ministry of Economy and Industry (MOEI) and the Asian Development Bank. This Environment monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Annual Safeguard Monitoring Report ___________________________________________________________________________ For FI operations Project Number: 3535 January-December 2018 Uzbekistan: Affordable Rural Housing Program (Financed by Asian Development Bank) For: Ministry of Economy and Industry Endorsed by: Management and Monitoring Unit February, 2019 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank ARHP - Affordable Rural Housing Program CCRA - Climate change risk assessment DLI - Disbursement Linked Indicator EA - Executing Agency EA - Executive Agency EIA - Environmental impact assessment EMP - Environmental Management Plan ESMS - Environmental and Social Management System HQ - Head Quarter IA - Implementation Agency IB - Ipoteka Bank IEE - Initial Environmental Examination MMU - Management -

The Need to Develop Public-Private Partnerships in the Radical Reform of Preschool Education in the Republic of Uzbekistan

769 International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies (IJPSAT) ISSN: 2509-0119. © 2021 International Journals of Sciences and High Technologies http://ijpsat.ijsht‐journals.org Vol. 25 No. 2 March 2021, pp. 247-253 The Need To Develop Public-Private Partnerships In The Radical Reform Of Preschool Education In The Republic Of Uzbekistan Xodjaeva Yulduz Mansurovna Independent researcher at the Fergana Polytechnic Institute Abstract – This article discusses the need to develop public-private partnerships in the radical reform of preschool education in the Republic of Uzbekistan. Keywords – Education, Private Partnership, Preschool Education, Public-Private Partnership, Private Business, Preschool Education, Non-Governmental Organizations. I. INTRODUCTION In his Address to the Oliy Majlis on January 24, 2020, President of the Republic of Uzbekistan Shavkat Mirziyoyev said: “Thirdly, if we aim to turn Uzbekistan into a developed country, we can achieve this only through rapid reforms, science and innovation. To do this, first of all, we need to nurture a new generation of knowledgeable and qualified personnel who will emerge as enterprising reformers, think strategically. That is why we have started to reform all levels of education, from kindergarten to higher education. In order to raise the level of knowledge not only of young people, but also of all members of our society, first of all, knowledge and high spirituality are needed. Where there is no knowledge, there will be backwardness, ignorance and, of course, misguidance. As the sages of the East say, "The greatest wealth is intelligence and knowledge, the greatest heritage is good upbringing, the greatest poverty is ignorance!" Therefore, the acquisition of modern knowledge, true enlightenment and high culture is a vital need for all of us.