The East India Marine Society's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Form

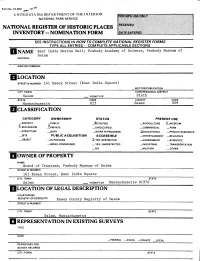

Form No. 10-300 \pffit-. \Q-1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME East India Marine Hall; Peabody Academy of Science, Peabody Museum of Salem HISTORIC AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 161 Essex Street (East India Square) _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Salem VICINITY OF Sixth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Essex 009 QCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC -JbcCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Board of Trustees, Peabody Museum of Salem STREET & NUMBER 161 Essex Street, East India Square CITY. TOWN STATE Salem _ VICINITY OF Massachusetts 01970 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Essex County Registry of Deeds STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Salem, Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _ UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE East India Marine Hall, erected in 1824-25, stands on the south side of Essex Street (now Essex Mall in this block), just west of Liberty Street. The unidentified architect created a handsome and dignified composition, constructed in granite on the narrow front and brick on the long sides and rear. -

History of the College

History of the College A liberal arts education in colonial America was a privilege enjoyed by few individuals. The nine colleges that existed pri- or to the American Revolution did not mean to be popular institutions. But the Revolution altered this state of affairs, and as the floodgates opened to the rising democratic tide, numerous colleges and universities were chartered in the young republic. The westward movement, growing populations, increasing wealth, state loyalties, and denominational rivalries all played a part in the early expansion of American higher education. Perhaps as many as 100 colleges tried and failed before the Civil War. Allegheny, founded in 1815, is one of the hardy survivors that testifies daily to the pioneer determination and vision of higher education in America. Foundation and Early Years the contributions that Alden had collected in the East. Allegheny is situated in Meadville, Pennsylvania, which was founded in Despite such generous gifts, however, the first years were difficult 1788 in the French Creek Valley, astride the route traversed by George ones. Both students and funds remained in short supply, and in vain Washington on his journey to Fort LeBoeuf a generation earlier. When the trustees turned for support to the Legislature of Pennsylvania and the College was established, Meadville was still a raw frontier town of the Presbyterian Church, of which Alden was a minister. Over Alden’s about 400 settlers, of whom an unusually large number had come from vigorous protests in the name of a classical liberal arts curriculum, the Massachusetts and Connecticut. These pioneers had visions of great trustees even entertained a proposal to turn the College into a military things for their isolated village, but none required greater imagination academy in order to attract support. -

A Historical Note on Joseph Smith's 1836 Visit to the East India Marine

Baugh: Joseph Smith’s Visit to the East India Marine Society Museum 143 A Historical Note on Joseph Smith’s 1836 Visit to the East India Marine Society Museum in Salem, Massachusetts Alexander L. Baugh During the last week of July 1836, Joseph Smith, in company with Sidney Rigdon, Hyrum Smith, and Oliver Cowdery, left Kirtland, Ohio, to investigate the possibility of acquiring some kind of treasure reported to have been lo- cated in a house in Salem, Massachusetts. Mormon leaders in Kirtland were made aware of the treasure-cache by a Church member named Burgess whose report obviously convinced Joseph Smith to investigate personally the possi- bility of obtaining it. The Prophet’s historic “mission” to Salem has generated considerable attention over the years, primarily because of the rather unusual motive behind such an undertaking. Additionally, while in Salem, Joseph Smith received a revelation (D&C 111) that provided important instructions concerning a number of questions he had concerning what course of action he and his companions should take during their stay in the city. It is not the focus of this essay to examine in any great length the 1836 Salem mission. My purpose is to highlight one small incident associated with that episode—the visit by Joseph, Sidney, and Hyrum to the East India Marine Society museum.1 Only a brief synopsis of the Salem trip will be given here. ALEX A N D ER L. BA UG H ([email protected]) is an associate professor of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University. He received his BS from Utah State University, and his MA and PhD degrees from Brigham Young University. -

Asher Benjamin As an Architect in Windsor, Vermont

Summer 1974 VOL. 42 NO.3 The GpROCEEDINGS of the VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY This famous architect built a meetinghouse and three private houses in Windsor before he left for Boston in 1802 ... Asher Benjamin as an Architect in Windsor, Vennont By JOHN QUINAN N August of 1802 the architect Asher Benjamin wrote from Boston to I Gideon Granger, the Postmaster General of the United States, seeking aid in obtaining a commission for a marine hospital in that city. Benjamin's letter identifies by name and location most of his first eight commissions - a rare and unusual document in American architectural history which enables us to trace his path northward from Hartford, Con necticut, to Windsor, Vermont. Benjamin wrote, in part: "Sir, I have since I left Suffield Conn. built the following houses, Viz. Samuel Hinckley, Northampton, William Coleman's Greenfield, Luke Baldwin's Esq., Brookfield, and a Meeting House and three other large houses in Windsor, Vermont, The Academy at Deerfield. l Most of these commissions have not fared very well. The Deerfield Academy building (Memorial Hall, 1798-1799) was altered sufficiently during the nineteenth century to obscure much of its original character. The Baldwin and Hinckley houses (both c.17%) were demolished early in the twentieth century and are lost to us, and it seems that the William Coleman house in Greenfield (1797) (Fig. 6) is the sole survivor of Benjamin's first decade of practice. But what of the four unnamed build ings in Windsor? Are they identifiable? Do they still stand in Windsor? Have they any special interest or significance? The four Windsor buildings are identifiable despite the fact that the three houses have been demolished and the meetinghouse has been altered I. -

Collections of the Original Library of Allegheny College, 1819-1823

Observations on the Winthrop, Bentley Thomas and 'Ex Dono' Collections of the Original Library of Allegheny College, 1819-1823, First listed by President Timothy Alden in Catalogus Bibliothecae Collegii Alleghaniensis, E Typis Thomae Atkinson Soc. apud Meadville. 1823. Edwin Wolf, 2nd Mr. Edwin Wolf, 2nd, Librarian of The Library Company of Philadelphia, was commissioned by Allegheny College to make a survey of the Original Library, March 6-16, 1962. Notes: Through his observations, Mr. Wolf uses the original spelling of the College's name: Alleghany. This document is a typed transcript of Mr. Wolf’s original work. Permission to publish this document has been granted by the Library Company of Philadelphia. The library of Alleghany as it existed when Timothy Alden made his catalogue of it in 1823 has importance today for several reasons: 1) it was the most scholarly library in the west, which was the result of its major component parts; 2) the component parts were distinguished in their day: the Bentley collection, strong in the classics, moderately strong in the church fathers and representative in theology and linguistics; the Winthrop collection, amazingly strong in linguistics and in voyages and travels, representative in the classics and, because of the influence of John Winthrop, important in the sciences; the Thomas collection, a typical early 19th- century selection of books; 3) the early and interesting provenance of many of the volumes throw light upon an earlier New England culture; 4) there is a present day scholarly interest in individual titles which are of great rarity and/or have considerable value. -

John Winthrop (1587/88-1649), 1798 Samuel Mcintire (1757-1811

John Winthrop (1587/88-1649), 1798 Samuel McIntire (1757-1811) carved and painted wood 15 1/2 (h) (39.370) inscribed on the base: "Winthrop” Bequest of William Bentley, 1819 Weis 149 Hewes number: 155 Ex. Coll.: commissioned by the donor, 1798. Exhibitions: 1804, Independence Day Celebration, Salem Meeting House. 1931, "American Folk Sculpture," Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey. 1957, "Samuel McIntire," Essex Institute, no. 8. 1977, "Landscape and Faction: Spatial Transformation in William Bentley's Salem," Essex Institute, no. 18. Publications: "Editor's Attic," The Magazine Antiques 21(January 1932): 8, 12. "Editor's Attic," The Magazine Antiques 28(October 1935): 138-40. Fiske Kimball, Mr. Samuel McIntire, Carver, The Architect of Salem (Portland, Maine: Southworth-Anthoensen Press, 1940): 138, fig. 362. Nina Fletcher Little, "Carved Figures by Samuel McIntire and his Contemporaries," Essex Institute Historical Collections 93(April-July 1957): 195-96, fig. 48. Susan Geib, "Landscape and Faction: Spatial Transformation in William Bentley's Salem," Essex Institute Historical Collections 113(July 1977): 217. This bust of John Winthrop was carved nearly one hundred and fifty years after the governor's death. It was commissioned by the Salem minister William Bentley (cat. #8) in 1798 as an addition to his "cabinet" of portraits of famous Massachusetts politicians and ministers. Bentley owned a painted miniature of the governor (cat. #154) that had been copied from a large seventeenth century canvas (cat. #153). Bentley loaned this miniature to the carver, Samuel McIntire, for the artist to use as reference for the carving. Bentley was familiar with the carver and his work. -

Federalist Politics and the Unitarian Controversy Marc M

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship Winter 2002 The orF ce of Ancient Manners: Federalist Politics and the Unitarian Controversy Marc M. Arkin Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Marc M. Arkin, The Force of Ancient Manners: Federalist Politics and the Unitarian Controversy, 22 J. of the Early Republic 575 (2002) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/716 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORCE OF ANCIENT MANNERS: FEDERALIST POLITICS AND THE UNITARIAN CONTROVERSY REVISITED Marc M. Arkin Some of our mutual friends say all is lost-nothing can be done. Nothing is to be done rashly, but mature counsels and united efforts are necessary in the most forlorn case. For though we may not do much to save ourselves, the vicissitudes of political fortune may do every thing-and we ought to be ready when she smiles.1 As 1804 drew to a close, Massachusetts Federalists could be forgiven for thinking that it had been a very bad year, the latest among many. -

Charles Bulfinch's Popularity Flourished in the 1790'S After Articles

Charles Bulfinch's popularity flour ished in the 1790's after articles and images of the Ho llis Street Church, his first major project, were publ ished . The images led lo two ear ly church commissions ou tside of Boston an d signaled the beginning ofBu lfinch 's growing inlluence on New England ch urch architecture. The church comm issions also led to a wide variety of requests for Bulfinch designed institu tional buildings. such as court houses. banks and collegiate arch itecture, as well as designs for private mansions, evidence of which can be found in Salem, Massachusells and Maine. Bulfinch's chu rch designs had several innovat ive elements . Traditiona lly, lhe entrances lo a New England sty le meeting houses, where relig ious and public meetings were held, had been placed on the short ax is of the building where members entered from the sides. Bulfinch reorganized this design along the lines of a classical Latinate plan, placing the entrance on the long ax is at the front of the church and pulpit at the far end. He also brough t the free sta nding tower and steeple back into the body of the bui lding, above the entrance w ith a pedimen t porch to suppor t it. The two churches which began this trend were the Congregat ional Churches in Pittsfield (1793) an d Taunton (1792), very sim ilar in design, and wide ly copied thro ughout the New Englan d area . Other churches Bulfinch worked on outside of Boston were the Old South Church in Hallowell, Maine, where he designed the Cupola (1806), and the Church of Chris t in Lancaster, Massachusetts . -

Prominent Journalist Rebuilt Stone M. E. Church Was

EXAMS IN 4 WEEKS THE CAMPUS EXAMS IN 4 WEEKS OF ALLEGHENY COLLEGE VOL. XLVI, NO. 23 MEADVILLE, PENNSYLVANIA MAY 2, 1928 PROMINENT JOURNALIST REBUILT STONE M. E. CHURCH WAS TENTATIVE SCHEDULE JOHN ARTHUR 6IBSON ALUMNUS OF ALLEfillENY DEDICATED LAST SUNDAY MORNING FOR EXAMS ANNOUNCED IS NOMINATED AGAIN STARTED NEWSPAPER WORK AS STUDENTS MUST REPORT ALL ALUMNI TRUSTEE NAMED FOR COMPETITOR ON STAFF CONFLICTS TO OFFICE FOURTH TERM IN OF "THE CAMPUS" AT ONCE THAT OFFICE Monday, May 28 John Arthur Gibson '91, Superintend- 'William Preston Beazell '97, nomi- nated for Alumni Trusteeship, has a A. M. P. M. ent of the Butler Public Schools, was threefold tie with Allegheny, for his Biology II Biology III recently nominated to serve a fourth father was Benjamin F. Beazell, D. D. Economics I Biology IV term as Alumni Trustee by the Alumni '68, and his wife, Isabel Howe '96. Al- Education III English Lang. V of his district. His ceaseless inter- though he did not come to Allegheny English Lit. IX English Lit. II est in the betterment of Allegheny until his junior year he was actively French VII French VI College has gained for him wide popu- identified with college affairs from the Latin I Geology I larity, and this recent honor conferred time of his arrival. He was a member Physics V Mathematics IM upon him by his contingent, is a dem- of Phi Delta Theta, on the editorial Pol. Science H onstration of the trust and confidence placed in him. An educator of note boards of both the Campus and the Tuesday, May 29 since his graduation, he has taken an Kaldron, president of the Oratorical Biology V Philosophy II active part in the progress of the But- Association and a member of the first Chemistry III Philosophy Hi ler Public School system. -

City of Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update

2015 City of Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update City of Salem Department of Planning and Community Development Prepared by: Community Opportunities Group, Inc. Unless noted otherwise, all images in this document provided by Patricia Kelleher, Community Opportunities Group, Inc. The Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Secretary of the Commonwealth William Francis Galvin, Chairman. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission. This program received Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office for Equal Opportunity, National Park Service, 1849 C Street NW, Washington, DC 20240. Table of Contents Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter 1 – Historic Overview of Salem ……………………………………………............ 18 Preservation Timeline …………………………………………………………….. 25 Chapter 2 – Salem Today ……………………………………………………………………….. 27 Historic Neighborhoods …………………………………………………………. 29 Historic Resources ………………………………………………………………… 41 Publicly-Owned Historic Resources ……………………………………………. 51 Overview of Previous Planning Studies ………………………………………… 59 Agencies & Organizations Engaged in Preservation Efforts …………………. 65 Chapter 3 - Existing Planning Efforts, Regulations & Policies………………………………. 76 Salem’s Historic Resource Inventory ….……………………………………….. -

William Bentley

WILLIAM BENTLEY (1759-1819), before 1826 James Frothingham (1786-1864) copy after his own composition oil on canvas 27 1/4 x 22 1/4 (69.22 x 56.50) Bequest of Hannah Armstrong Kittredge, 1917 Weis 10 Hewes Number: 8 Ex. Coll.: Possibly commissioned by Hannah Pippen Hodges (1768-1837); to her daughter Hannah Hodges Kittredge (1793-1877); to her daughter, the donor (1834-1916). Exhibitions: ‘Dr. Bentley’s Salem: Diary of a Town,’ Essex Institute, Salem, Mass., 1977. Publications: ‘Dr. Bentley’s Salem: Diary of a Town,’ Historical Collections of the Essex Institute 113 (July 1977): 34. Stefanie Munsing Winkelbauer, ‘William Bentley: Connoisseur and Print Collector,’ in Georgia B. Barnhill, ed., Prints of New England (Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1991), 22. The Reverend William Bentley was a noted bibliophile, scholar, historian, and linguist. He was the minister of the East Church (Unitarian) in Salem, Massachusetts, from 1783 to his death in 1819. In his remarkable diaries, the manuscripts of which are preserved at the American Antiquarian Society, Bentley recorded local and national events, shipping news, church business, scientific theories, and town gossip.1 He can be considered Salem’s first archivist, recording scraps of genealogical information and town history in his diary. He also commissioned several portraits of prominent New England leaders, most of which were copied after well-known canvases, and placed these replicas in his ‘cabinet.’ Bentley graduated from Harvard College in 1777 and, with a talent for languages, tutored Greek and Latin there while looking for a church position. After moving to Salem, Bentley began to contribute political and social commentary to the Salem Register. -

Heritage Education for School-Aged Children: an Analysis of Programs in Salem, Massachusetts

HERITAGE EDUCATION FOR SCHOOL-AGED CHILDREN: AN ANALYSIS OF PROGRAMS IN SALEM, MASSACHUSETTS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Historic Preservation Planning by Emily Joyce Giacomarra January, 2015 © 2015 Emily Joyce Giacomarra ABSTRACT Heritage education uses local resources and the built environment to teach students concepts and skills in the arts, humanities, sciences, and math. This can be manifest in interdisciplinary programs that would seem ideal for teaching students about historic preservation and instilling children with a preservation ethic. Additionally, place-based educational programs have demonstrated proven success in academic achievement, student engagement, and creating a sense of stewardship and understanding of the environment. Examining heritage education methods and experiences in Salem, Massachusetts provides a lens to investigate how public schools and historic sites are using these potential opportunities. Both the Salem Maritime National Historic Site, owned by the National Park Service, and the Peabody Essex Museum are located in Salem and provide free curriculum-based heritage educational programming for Salem Public Schools. These programs provide strong institutional support and are widely appreciated by public school teachers. Historic New England, based in Boston, offers education programs throughout the region at its many locations, some of which are used by Salem schools. All three organizations have made offering well-researched programs based on their historic resources a priority because of the widespread benefits apparent to students and their organizational missions. Although teachers espouse the benefits of these programs, the initiative and leadership needed to increase, improve, and strengthen these programs from inside the public schools is not currently present.