Salem in 1800

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

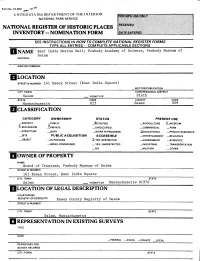

Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 \pffit-. \Q-1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME East India Marine Hall; Peabody Academy of Science, Peabody Museum of Salem HISTORIC AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 161 Essex Street (East India Square) _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Salem VICINITY OF Sixth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Essex 009 QCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC -JbcCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Board of Trustees, Peabody Museum of Salem STREET & NUMBER 161 Essex Street, East India Square CITY. TOWN STATE Salem _ VICINITY OF Massachusetts 01970 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Essex County Registry of Deeds STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Salem, Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _ UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE East India Marine Hall, erected in 1824-25, stands on the south side of Essex Street (now Essex Mall in this block), just west of Liberty Street. The unidentified architect created a handsome and dignified composition, constructed in granite on the narrow front and brick on the long sides and rear. -

A Historical Note on Joseph Smith's 1836 Visit to the East India Marine

Baugh: Joseph Smith’s Visit to the East India Marine Society Museum 143 A Historical Note on Joseph Smith’s 1836 Visit to the East India Marine Society Museum in Salem, Massachusetts Alexander L. Baugh During the last week of July 1836, Joseph Smith, in company with Sidney Rigdon, Hyrum Smith, and Oliver Cowdery, left Kirtland, Ohio, to investigate the possibility of acquiring some kind of treasure reported to have been lo- cated in a house in Salem, Massachusetts. Mormon leaders in Kirtland were made aware of the treasure-cache by a Church member named Burgess whose report obviously convinced Joseph Smith to investigate personally the possi- bility of obtaining it. The Prophet’s historic “mission” to Salem has generated considerable attention over the years, primarily because of the rather unusual motive behind such an undertaking. Additionally, while in Salem, Joseph Smith received a revelation (D&C 111) that provided important instructions concerning a number of questions he had concerning what course of action he and his companions should take during their stay in the city. It is not the focus of this essay to examine in any great length the 1836 Salem mission. My purpose is to highlight one small incident associated with that episode—the visit by Joseph, Sidney, and Hyrum to the East India Marine Society museum.1 Only a brief synopsis of the Salem trip will be given here. ALEX A N D ER L. BA UG H ([email protected]) is an associate professor of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University. He received his BS from Utah State University, and his MA and PhD degrees from Brigham Young University. -

The East India Marine Society's

Global Knowledge in the Early Republic The East India Marine Society’s “Curiosities” Museum Patricia Johnston On a cold January day in 1804, the Reverend William Bentley, pastor of the East Church, stood and watched a strange and exotic parade weaving through the streets of Salem, Massachusetts. A number of sea captains, who had just returned from Sumatra, Bombay, Calcutta, Canton, Manila, and other Asian ports, put on this public display to commemorate their recent business adventures. Bentley recorded in his diary, “This day is the Annual Meeting of the East India Marine Society. After business & before din- ner they moved in procession, . Each of the brethren bore some Indian curiosity & the palanquin was borne by the negroes dressed nearly in the Indian manner. A person dressed in Chinese habits & mask passed in front. The crowd of spectators was great.”1 The objects that the minister described demonstrate the global circula- tion of material culture in the Early Republic. Waiting in Asian harbors for trade opportunities, captains and crews swapped souvenirs that had literally circled the world. When they returned to their hometowns, they shared the objects they collected, both privately with acquaintances and publicly in mu- seums and parades that were widely covered in the newspapers. These global artifacts provide insights into the broad intellectual pursuits of the Early Republic, including natural history, ethnography, and aesthetics. The objects also illuminate early trade relations and cultural perceptions between Asia and the new United States. When displayed back in the United States, artifacts helped construct and reinforce social hierarchies in American seaports; they also expressed America’s arrival as a full participant in world commerce. -

City of Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update

2015 City of Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update City of Salem Department of Planning and Community Development Prepared by: Community Opportunities Group, Inc. Unless noted otherwise, all images in this document provided by Patricia Kelleher, Community Opportunities Group, Inc. The Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Secretary of the Commonwealth William Francis Galvin, Chairman. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission. This program received Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office for Equal Opportunity, National Park Service, 1849 C Street NW, Washington, DC 20240. Table of Contents Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter 1 – Historic Overview of Salem ……………………………………………............ 18 Preservation Timeline …………………………………………………………….. 25 Chapter 2 – Salem Today ……………………………………………………………………….. 27 Historic Neighborhoods …………………………………………………………. 29 Historic Resources ………………………………………………………………… 41 Publicly-Owned Historic Resources ……………………………………………. 51 Overview of Previous Planning Studies ………………………………………… 59 Agencies & Organizations Engaged in Preservation Efforts …………………. 65 Chapter 3 - Existing Planning Efforts, Regulations & Policies………………………………. 76 Salem’s Historic Resource Inventory ….……………………………………….. -

Heritage Education for School-Aged Children: an Analysis of Programs in Salem, Massachusetts

HERITAGE EDUCATION FOR SCHOOL-AGED CHILDREN: AN ANALYSIS OF PROGRAMS IN SALEM, MASSACHUSETTS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Historic Preservation Planning by Emily Joyce Giacomarra January, 2015 © 2015 Emily Joyce Giacomarra ABSTRACT Heritage education uses local resources and the built environment to teach students concepts and skills in the arts, humanities, sciences, and math. This can be manifest in interdisciplinary programs that would seem ideal for teaching students about historic preservation and instilling children with a preservation ethic. Additionally, place-based educational programs have demonstrated proven success in academic achievement, student engagement, and creating a sense of stewardship and understanding of the environment. Examining heritage education methods and experiences in Salem, Massachusetts provides a lens to investigate how public schools and historic sites are using these potential opportunities. Both the Salem Maritime National Historic Site, owned by the National Park Service, and the Peabody Essex Museum are located in Salem and provide free curriculum-based heritage educational programming for Salem Public Schools. These programs provide strong institutional support and are widely appreciated by public school teachers. Historic New England, based in Boston, offers education programs throughout the region at its many locations, some of which are used by Salem schools. All three organizations have made offering well-researched programs based on their historic resources a priority because of the widespread benefits apparent to students and their organizational missions. Although teachers espouse the benefits of these programs, the initiative and leadership needed to increase, improve, and strengthen these programs from inside the public schools is not currently present. -

Chief Operating Officer Salem, Massachusetts

Chief Operating Officer Salem, Massachusetts THE OPPORTUNITY The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) celebrates outstanding artistic and cultural creativity by collecting, stewarding, and interpreting objects of art and culture in ways that increase knowledge, enrich the spirit, engage the mind, and stimulate the senses. Through its exhibitions, programs, publications, media, and related activities, the museum strives to create experiences that transform people's lives by broadening their perspectives, attitudes, and knowledge of themselves and the wider world. As PEM enters the next era of its storied history following an unparalleled 25-year arc of development, the museum seeks an experienced and highly motivated leader to serve as its chief operating officer (COO). More than two centuries since its inception, PEM faces a distinct set of opportunities and challenges. In the wake of an international health crisis and systemic racial injustice that is experienced acutely by many and cannot be ignored, museum leaders have been called to action. This period will require expansive thinking and both global and local efforts as PEM examines its role as an inclusive, accessible, and thought- provoking leader in an evolving museum landscape and society. In July 2019, PEM appointed a new director and CEO for the first time in 25 years. A bold and visionary leader, Dr. Brian Kennedy has already laid the groundwork for an ambitious five-year strategic plan that will reevaluate the museum’s approach to and engagement of its audience, staff, physical and digital space, and financial resources. The COO will partner closely with Dr. Kennedy to realize the short- and long-term success of this vision. -

A NEW PEABODY MUSEUM for SALEM MASSACHUSETTS by Donald H

A NEW PEABODY MUSEUM FOR SALEM MASSACHUSETTS by Donald H. Panushka SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE ON AUGUST 29, 1951 Author Dean, School of Architecture and City Planning ABSTRACT A NEW PEABODY MUSEUM FOR SALEM MASSACHUSETTS by Donald H. Panushka Submitted for the degree of Master of Architecture in the Department of Architecture on August 29, 1951. The Peabody Museum of Salem, at present, is the oldest museum in existance in this country. It's collections are divided into three different categories: Maritime History, Ethnology, and Natural History of Essex County. Preliminary study for this thesis consisted of a study of the Museum's Historical background and an analysis of it's present site, buildings, and exhibition technique. As a result of this study and anal- ysis certain basic requirements were evolved in addition to the program proper. These were: to retain the Salem East India Marine Society Hall, integration with the Salem harbor and the moving to a new site. The last requirement of course necessitated moving the East India Hall, which proved to be economically sound. A site adjoining the National Maritime Historic site was chosen as the location of the new museum. This site is also close to the House of the Seven Gables and is in a thickly settled residential neighborhood. An attempt was made to recapture the maritime character which the museum possessed externally in the early nineteenth century and to coordinate the museum with the Maritime Historic site and the House of the Seven Gables, to form a unified whole. -

Prehistoric Archaeological Collections from Massachusetts

2 b 0276 1175 GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS COLLECTION JAN G - 1984 University of Massachusetts i^eositoqf Copy PREHISTORIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL COLLECTIONS FROM MASSACHUSETTS A REPORT OiN THE PEABODY MUSEUM OF SALEM Prehistoric Survey Team: Eric S. Johnson Thomas F. Mahlstedt Massachusetts Historical Commission November 1982 CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 History of the Peabody Museum of Salem 2 Past Research in Northeastern Massachusetts 5 Topography and Environment 13 Collection Bias 17 Collection Analysis: General Artifact Categories 22 Collection Analysis: Summary of Temporal/Cultural Phases 29 Specific Sites and Research Potential 38 Management Recommendations 43 Summary 45 Tables and Appendices 47 Sources Cited 53 I. Introduction The analysis and computer-coded inventory of the Peabody Museum of Salem represents the sixth study of its kind which the prehistoric survey team has completed. Previously, the archaeological collections of the Bronson Museum (Attleboro), Peabody Museum (Harvard University), the R. S. Peabody Foundation Museum (Andover) , the Benjamin Smith collection (Concord), and the Roy Athearn collection (Fall River) have been analyzed and entered into a computerized file. The primary goal of the survey, which for the past two and one half years has been sponsored by the Massachusetts Historical Commission, is to develop a standardized filing system and data base upon which informed decisions can be formulated concerning the management and preservation of the prehistoric cultural resources of the Commonwealth. The archaeological site files, computer inventories, and maps of the MHC represent the single most comprehensive facility in Massachusetts which can be used to assess the impacts of proposed construction projects on known or potential archaeo- logical resources. -

City of Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update

2015 City of Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update City of Salem Department of Planning and Community Development Prepared by: Community Opportunities Group, Inc. Unless noted otherwise, all images in this document provided by Patricia Kelleher, Community Opportunities Group, Inc. The Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Secretary of the Commonwealth William Francis Galvin, Chairman. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission. This program received Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office for Equal Opportunity, National Park Service, 1849 C Street NW, Washington, DC 20240. Table of Contents Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter 1 – Historic Overview of Salem ……………………………………………............ 18 Preservation Timeline …………………………………………………………….. 25 Chapter 2 – Salem Today ……………………………………………………………………….. 27 Historic Neighborhoods …………………………………………………………. 29 Historic Resources ………………………………………………………………… 41 Publicly-Owned Historic Resources ……………………………………………. 51 Overview of Previous Planning Studies ………………………………………… 59 Agencies & Organizations Engaged in Preservation Efforts …………………. 65 Chapter 3 - Existing Planning Efforts, Regulations & Policies………………………………. 76 Salem’s Historic Resource Inventory ….……………………………………….. -

Cooperative Collection Registers at the Peabody Museum of Salem and the Essex Institute

Commentaries and Case Studies 115 Format For Cooperation: Cooperative Collection Registers at the Peabody Museum of Salem and the Essex Institute ROBERT P. SPINDLER, GREGOR TRINKAUS-RANDALL, and PRUDENCE Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/51/1-2/115/2748105/aarc_51_1-2_63t0k41020127g57.pdf by guest on 02 October 2021 BACKMAN F. Gerald Ham wrote in 1981 that "inter- This essay analyzes the nature of the li- institutional cooperation is an essential fea- braries' respective collections, discusses the ture of a complex and interdependent tech- relationship between their collecting poli- nological society."1 Many cooperative cies and the need for this form of cooper- "archival strategies" have been imple- ation, and explains the development of a mented in an attempt to reap the potential format for the intellectual unification of benefits of interdependence. Most cooper- physically divided collections. It concludes ative archival projects, however, are con- with a discussion of other possible appli- cerned with collection development, often cations of this format. in association with archival networks.2 These The Essex Institute and the Peabody Mu- are laudable projects that set standards for seum of Salem, situated within a block of future collection development on a massive each other, have collected historic docu- scale, but there are other ways in which mentation since the beginning of the nine- cooperation can enhance archival activi- teenth century. The majority of the ties. manuscript collections consists of the pa- One such activity could be to improve pers of Salem merchant families whose ships access to collections currently divided be- participated in trade with ports in India, tween two or more institutions. -

Salem Downtown Renewal Plan Cover.Indd

Salem Downtown Renewal Plan Submitted to: Salem Redevelopment Authority Submitted by: The Cecil Group, Inc. October 27, 2011, as amended November 17, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary Introduction E-1 New Effective Dates E-1 Consolidation of Previous Plans and Prior Plan Changes E-2 Summary of Plan Changes E-4 Other State Filings E-9 Format E-10 Severability E-10 1. Characteristics of the Site (760 CMR 12.02 (1)) 1.1 Description of the Plan Area 1-1 1.2 Existing Uses 1-5 1.3 Current Zoning 1-7 1.4 Historical Commission 1-14 1.5 Design Review Board 1-16 2. Eligibility (760 CMR 12.02(2)) 2.1 Major Plan Change 2-1 2.2 Local Survey and Conformance with the Comprehensive Plan for 2-1 Salem 3. Objectives (760 CMR 12.02 (3)) 3.1 Plan Goals and Objectives 3-1 3.2 Plan Activities 3-2 3.3 Design Review 3-4 Section 1. Process and Applicability of the Standards 3-4 Section 2: Design Criteria 3-8 Section 3: Design Standards 3-9 4. Requisite Municipal Approvals (760 CMR 12.02 (5)) 4.1Salem Redevelopment Authority Approval 4-2 4.2 Planning Board Approval 4-3 4.3 City Council Approval 4-4 4.4 Opinion of Counsel 4-6 5. Citizen Participation (760 CMR 12.02 (11)) 5.1 Participation in Plan Development 5-1 5.2 Participation in Project Execution 5-3 6. Future Plan Changes (760 CMR 12.03) 6.1 Future Plan Changes 6-1 Appendix I: Minutes of Public Meetings Appendix II: Media Reports Appendix III: Salem Commercial Design Guidelines Appendix IV: Notification of Redevelopers and Property Owners Appendix V: Salem Historical Commission Guidelines Notebook Appendix VI: Approval from Department of Housing and Community Development Appendix VII. -

The Salem Project Study of Alternatives

0-:3" File: Salem Mariltine. • The Project Study of Alternatives -), J ~CHN\CAl INFORMATION CENID'l ON MICROfiLM DENVER SERVICE CENTER SCANNED NATIONAL PARK SERVICE --, OSC-PGr ...J. /?JOI"",..son United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Salem Maritime National Historic Site it: IN REFLY REFER TO: 174 Derby Street Salem, Massachusetts 01970 (508) 744-4323 REC'O·OSC·PGT TECH. INFO. CTR. AUG 211991 July 31, 1991 On behalf of th~ National Park Service, we would like you to have a copy of the SaleM Project Study of Alternatives. On June 19th of this year, the U.S. Congress officially received the Study. Now that the Study has been tranSMitted to Congress, we can release the full docuMent with its technical background inf~r.ation to you. We hope as you read this dOCUMent that you will becoMe Mare aware and fully appreCiate the breadth and Quality of resources located in Essex County. If you have any Questions or concerns, please write or call Cynthia Pol~lack. Our door is always open. ~~~ Cynthia Pollack Project Director ~f.ff Planning Director The Sale. Project The SaleM Project ------------~~ ~-~-~- , ''',I ., NATIONAL PARK SERVICE PLANNING TEAM RECOMMENDED ACTION FOR THE SALEM PROJECT STUDY OF ALTERNATIVES • The enclosed Study ojAlternatives for the Salem Project explores several alternative ways of preserving the rich cultural heritage of Salem, Massachusetts, and related sites in Essex County, and using the county's significant resources to stimulate cultural awareness and economic development through tourism. The Salem Project is based out of Salem Maritime National Historic Site, a 9-acre site along the Salem waterfront that has outstanding resources to initiate a nationally significant story of America's early settlement, maritime era, and early industrial development.