Using the Local to Tell a Global Story:How The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Form

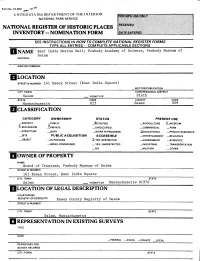

Form No. 10-300 \pffit-. \Q-1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME East India Marine Hall; Peabody Academy of Science, Peabody Museum of Salem HISTORIC AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 161 Essex Street (East India Square) _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Salem VICINITY OF Sixth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Essex 009 QCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC -JbcCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Board of Trustees, Peabody Museum of Salem STREET & NUMBER 161 Essex Street, East India Square CITY. TOWN STATE Salem _ VICINITY OF Massachusetts 01970 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Essex County Registry of Deeds STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Salem, Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _ UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE East India Marine Hall, erected in 1824-25, stands on the south side of Essex Street (now Essex Mall in this block), just west of Liberty Street. The unidentified architect created a handsome and dignified composition, constructed in granite on the narrow front and brick on the long sides and rear. -

Builders' Rule Books Published in America

Annotated Bibliography of Builders' Rule Books Published in America Note: Content for this bibliography was originally developed in the 1970s. This version of the bibliography incorporates some preliminary edits to update information on the archives involved and the location of some of the rule books. HPEF intends to continue to update the information contained in the bibliography over time. If you have corrections or information to add to the bibliography, please contact: [email protected] Elizabeth H. Temkin Summer Intern - 1975, 1976 National Park Service Washington, DC Library Information American Antiquarian Society 185 Salisbury St. Worcester, MA 01609 American Institute of Architects National Office 1735 New York Ave., NW Washington, DC Avery Library Columbia University New York, NY Baker Library Harvard University School of Business Soldiers Field Road Boston, MA Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library Yale University New Haven, CT Boston Athenaeum 10-1/2 Beacon St. Boston, MA Boston Public Library 666 Boylston St. Boston, MA John Carter Brown Library Brown University Providence, RI Essex Institute l32A Essex St. Salem, MA Bostonian Society Old State House 206 Washington St. Boston, MA Carpenters’ Company of the City and County of Philadelphia Carpenters' Hall Philadelphia, PA Chester County Historical Society 225 North High Street West Chester, PA 19380-2658 University of Cincinnati Library University of Cincinnati Cincinnati, OH Free Library of Philadelphia Logan Square Philadelphia, PA Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Museum San Marino, CA University of Illinois Architecture Library Arch Building University of Illinois Urbana. IL Indiana Historical Society 140 N. Senate Ave. Indianapolis, IN Indiana State Library Indiana Division 140 N. -

Salem for All Ages: Needs Assessment Results

Salem for All Ages: Needs assessment results Prepared by the Center for Social & Demographic Research on Aging Gerontology Institute, University of Massachusetts Boston In partnership with The City of Salem NOVEMBER 2016 Acknowledgements We acknowledge with gratitude our partnership with the City of Salem and members of its Salem for All Ages Leadership Team including Kimberly Driscoll, Mayor of Salem, Patricia Zaido, resident leader, Christine Sullivan, resident leader, Dominick Pangallo, Chief of Staff, Mayor’s Office, Meredith McDonald, Director, Salem Council on Aging, Tricia O’Brien, Superintendent, Salem Department of Parks, Recreation and Community Services. This effort could not be completed without the guidance and expertise from Mike Festa, Massachusetts State Director at AARP, Kara Cohen, Community Outreach Director at AARP of Massachusetts, and the Jewish Family & Children’s Services organization. Specifically, the efforts of Kathy Burnes, Division Director of Services for Older Adults and program coordinator, Kelley Annese, who completed the Salem for All Ages report. The support from North Shore Elder Services has been phenomenal and so we would like to thank Executive Director Paul Lanzikos and Katherine Walsh who serves as Chair of the Board of Director. We recognize the excellence of our research assistance from University of Massachusetts students Molly Evans, Naomi Gallopyn, Maryam Khaniyan, and Ceara Somerville. Most importantly, we are grateful to all of the residents and leaders in Salem who gave of their time to -

2012 Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Humanities

EXPLORING THE HUMAN ENDEAVOR NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES 2ANNU0AL1 REP2ORT CHAIRMAN’S LETTER August 2013 Dear Mr. President, It is my privilege to present the 2012 Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Humanities. For forty-seven years, NEH has striven to support excellence in humanities research, education, preservation, access to humanities collections, long-term planning for educational and cultural institutions, and humanities programming for the public. NEH’s 1965 founding legislation states that “democracy demands wisdom and vision in its citizens.” Understanding our nation’s past as well as the histories and cultures of other peoples across the globe is crucial to understanding ourselves and how we fit in the world. On September 17, 2012, U.S. Representative John Lewis spoke on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial about freedom and America’s civil rights struggle, to mark the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. He was joined on stage by actors Alfre Woodward and Tyree Young, and Howard University’s Afro Blue jazz vocal ensemble. The program was the culmination of NEH’s “Celebrating Freedom,” a day that brought together five leading Civil War scholars and several hundred college and high school students for a discussion of events leading up to the Proclamation. The program was produced in partnership with Howard University and was live-streamed from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History to more than one hundred “watch parties” of viewers around the nation. Also in 2012, NEH initiated the Muslim Journeys Bookshelf—a collection of twenty-five books, three documentary films, and additional resources to help American citizens better understand the people, places, history, varieties of faith, and cultures of Muslims in the United States and around the world. -

A Historical Note on Joseph Smith's 1836 Visit to the East India Marine

Baugh: Joseph Smith’s Visit to the East India Marine Society Museum 143 A Historical Note on Joseph Smith’s 1836 Visit to the East India Marine Society Museum in Salem, Massachusetts Alexander L. Baugh During the last week of July 1836, Joseph Smith, in company with Sidney Rigdon, Hyrum Smith, and Oliver Cowdery, left Kirtland, Ohio, to investigate the possibility of acquiring some kind of treasure reported to have been lo- cated in a house in Salem, Massachusetts. Mormon leaders in Kirtland were made aware of the treasure-cache by a Church member named Burgess whose report obviously convinced Joseph Smith to investigate personally the possi- bility of obtaining it. The Prophet’s historic “mission” to Salem has generated considerable attention over the years, primarily because of the rather unusual motive behind such an undertaking. Additionally, while in Salem, Joseph Smith received a revelation (D&C 111) that provided important instructions concerning a number of questions he had concerning what course of action he and his companions should take during their stay in the city. It is not the focus of this essay to examine in any great length the 1836 Salem mission. My purpose is to highlight one small incident associated with that episode—the visit by Joseph, Sidney, and Hyrum to the East India Marine Society museum.1 Only a brief synopsis of the Salem trip will be given here. ALEX A N D ER L. BA UG H ([email protected]) is an associate professor of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University. He received his BS from Utah State University, and his MA and PhD degrees from Brigham Young University. -

Bulletin of the Essex Institute, Vol

i m a BULLETIN OF THE ESSEX IlsTSTITUTE]. Vol. 18. Salem: Jan., Feb., Mar., 1886. Kos. 1-3. MR. TOPPAN'S NEW PROCESS FOR SCOURING WOOL. JOHN RITCHIE, JR. Read before the Essex Institute, March 15, 1886, Ladies and Gentlemen^ — Two years ago, almost to a day, I had the pleasure of discussing before you what was at that time a new process of bleaching cotton and cotton fabrics, — process which, since that day, has been developed with steadily increasing value by a company doing business under Mr. Top- pan's inventions. This evening [March 15] I desire your attention to a consideration of the effects of the same solvent principle upon that other great textile material, wool. The lecture of two years ago was illustrated by the pro- cesses themselves, practically performed before your eyes. It is our intention this evening to follow out the same plan and to illustrate and, so far as may be, prove by experiment the statements which shall be made. It is our intention to scour upon the platform various speci- mens of wool, and as well, to dye before you such colors as can be fixed within a time which shall not demand, upon your part, too much of that virtue, patient waiting. Mr. Toppan, who needs no introduction to this audience, will undertake, later in the evening, the scouring of wool, and Mr. Frank Sherry, of Franklin, has kindly offered to assist in the work of dyeing. To those of you who are not familiar with the authorities in this country, in the work of dyeing, I need only say, that Mr. -

HISTORIC RESOURCES SURVEY UPDATE, 2018-2019 Survey Final Report

HISTORIC RESOURCES SURVEY UPDATE, 2018-2019 Survey Final Report Submitted to the City of Beverly, Department of Planning and Development and Beverly Historic District Commission 20 February 2019 Wendy Frontiero and Martha Lyon, Preservation Consultants ABSTRACT The City of Beverly’s Department of Planning and Development, together with the Beverly Historic District Commission, have used Community Preservation funds to continue work on the city-wide inventory of historic properties. This survey project recorded historically, architecturally, and visually significant resources representing the cultural history of Beverly from the late 19th through early 20th centuries, focusing on residential buildings and landscapes. The consultants prepared three new MHC Form B- Building forms, two Form H – Landscape forms, and two Form A – Area forms; the City developed a base map locating and identifying surveyed properties. This Survey Final Report includes a methodology statement; index of inventoried properties; National Register of Historic Places context statement with recommendations for National Register listings; further study recommendations; and a bibliography. In addition to promoting the understanding and appreciation of Beverly’s historic resources, the survey project may be useful in supporting additional preservation planning efforts, including demolition delay and Great Estate zoning. Historic resources recorded in the survey will be incorporated into the Inventory of Historic and Archaeological Assets of the Commonwealth, maintained by the Massachusetts Historical Commission. Copies of all inventory forms, the final report, and the survey base map are available for public inspection at the offices of the Department of Planning and Development. Electronic copies of the survey forms are available on the City of Beverly’s website, at http://www.beverlyma.gov/boards-commissions/historics-district-commission/ . -

VERTICAL FILE A-CH Abbott Rock Acid Spill (Salem)

VERTICAL FILE A-CH Bertram Field Abbott Rock Bertram, John Acid Spill (Salem) Bertram Home for Aged Men Agganis, Harry Bewitched Statue Almshouse Bibliographies Almy’s American Model Gallery Biographies Andrew-Safford House Bicentennial (Salem) Annadowne Family (aka Amadowne) Bicentennial Monument Arbella Bike Path Architecture, Salem Black History Armory (Salem) Armory Park Black Picnic Artsalem Blaney Street Wharf Art Colloquim (Salem) Blubber Hollow Authors (Salem) Boat Business Ayube, Sgt. James Bold Hathorne (Ballad) Bands, Salem Brass Boston Gas Storage Tank Banks Barry, Brunonia (Author) Boston, Massachusetts Baseball Boston Street Batchelder, Evelyn B. Longman (sculptor) Bowditch, Nathaniel Beane, Rev. Samuel Bowditch Park Bell, Alexander Graham Bowling, Billiards and Bookies Belle, Camille (Ma Barker Boys and Girls Club Benson, Frank W. (artist) Bradbury, Benjamin Bentley, William Bradbury, Thomas Bernard, Julia (artist) Bradstreet, Anne Cat Cove Marine Lab Bridge Street Cemeteries Broderick, Bill Central Street Brookhouse Home VERTICAL FILE CH-G Brown, Joshua (shipbuilder) Challenger Program (Little League program) Chamber of Commerce Browne, Ralph Chamberlain, Benjamin M. (jeweler) Smith & Brunson, Rick (athlete) Chamberlain Buczko, Thaddeus Chandler, Joseph Charter, Salem of Buffum, Robert Charter Commission Burnham, Craig (inventor) Charter Street Burial Ground Businesses (#1) Chesapeake and Shannon (Battle) Businesses (#2) Chestnut Street Bypass Road Chestnut Street Days Cabot, Joseph (House) Children’s Island Children’s -

The East India Marine Society's

Global Knowledge in the Early Republic The East India Marine Society’s “Curiosities” Museum Patricia Johnston On a cold January day in 1804, the Reverend William Bentley, pastor of the East Church, stood and watched a strange and exotic parade weaving through the streets of Salem, Massachusetts. A number of sea captains, who had just returned from Sumatra, Bombay, Calcutta, Canton, Manila, and other Asian ports, put on this public display to commemorate their recent business adventures. Bentley recorded in his diary, “This day is the Annual Meeting of the East India Marine Society. After business & before din- ner they moved in procession, . Each of the brethren bore some Indian curiosity & the palanquin was borne by the negroes dressed nearly in the Indian manner. A person dressed in Chinese habits & mask passed in front. The crowd of spectators was great.”1 The objects that the minister described demonstrate the global circula- tion of material culture in the Early Republic. Waiting in Asian harbors for trade opportunities, captains and crews swapped souvenirs that had literally circled the world. When they returned to their hometowns, they shared the objects they collected, both privately with acquaintances and publicly in mu- seums and parades that were widely covered in the newspapers. These global artifacts provide insights into the broad intellectual pursuits of the Early Republic, including natural history, ethnography, and aesthetics. The objects also illuminate early trade relations and cultural perceptions between Asia and the new United States. When displayed back in the United States, artifacts helped construct and reinforce social hierarchies in American seaports; they also expressed America’s arrival as a full participant in world commerce. -

Cunningham, Henry Winchester, Papers, 1893-1912 Misc

American Antiquarian Society Manuscript Collections NAME OF COLLECTION : LOCATION : Cunningham, Henry Winchester, Papers, 1893-1912 Misc. mss. boxes "C" SIZE OF COLLECTION : 4 folders (45 items) SOURCES OF INFORMATION ON COLLECTION : For biographical information on Cunningham, see PAAS , 41 (1932), 10-13. For genealogical information on Remick, see Winifred Lovering Holman, Remick Genealogy ... 1933. SOURCE OF COLLECTION : Remick materials, the gift of Henry Winchester Cunningham, 1920 COLLECTION DESCRIPTION : Henry Winchester Cunningham (1860-1930) was an active genealogical and historical researcher, aiding in the administration of several societies, including the New England Historic Genealogical Society, The Colonial Society, Bostonian Society, The Massachusetts Historical Society, and the American Antiquarian Society. Christian Remick (1726- ) was a marine and townscape painter in watercolor, as well as a sailor and master mariner who served on privateers during the Revolution. This collection includes correspondence to and from Cunningham in his search for genealogical and biographical information, as well as information on several works, of Christian Remick. The correspondents include Robert Noxon Toppan (1836-1901), of the Prince Society; Edmund Farwell Slafter (1816-1906); William Henry Whitmore (1836-1900); James Phinney Baxter (1831-1921); Edmund March Wheelwright (1854-1912); Worthington Chauncey Ford (1858-1941); J. O. Wright ( - ); Carlos Slafter (1825-1907); Frank Warren Hackett (1841-1926); Fanny Whitmore ( - ); George Francis Dow (1868-1936), of the Essex Institute; Sidney Lawton Smith (1845-1919); Charles Eliot Goodspeed (1867-1950); J. A. Remick ( - ); A. T. S. Goodrich ( - ); and A. W. Davis ( - ), as well as the town clerks in Harwich, Orleans, and Barnstable, Mass. Included also is a printed copy of a paper, written by Cunningham, entitled Christian Remick—An Early Boston Artist , published by the Club of Odd Volumes in 1904. -

The Boston Athenæum, Transatlantic Literary Culture, and Regional Rivalry in the Early Republic

Origin Stories: The Boston Athenæum, Transatlantic Literary Culture, and Regional Rivalry in the Early Republic lynda k. yankaskas RITING of the Boston Athenæum’s founding in his 1861 W memoirs, Robert Hallowell Gardiner traced the inspira- tion for the new literary institution some fifty years before to a specific moment. The Athenæum, he explained, was the work of Boston’s Anthology Society, a group of young men who came together in 1805 to publish the Monthly Anthology.Likeother early nineteenth-century periodicals, the Anthology published essays on literature written by its board of editors, the results of scientific investigations on everything from toes to cats, and a miscellany of other prose. Gardiner, scion of a wealthy Maine family and Anthology Society member, described how the So- ciety, in accordance with common practice, accepted books in exchange for its periodical, and soon found itself with more volumes than space to house them. Short of funds as well as space, the Society resolved at the end of 1806 to reinvent it- self as a membership library, open to a much wider circle than contributors to the Anthology alone. The specific form of this I am grateful to James Green of the Library Company of Philadelphia, the Early Americanists of the Lehigh Valley, and the Quarterly’s editors for their comments on earlier drafts of this article, and to the Muhlenberg College Provost’s Office for financial support that made possible my research in Liverpool. I also thank the staffs of the Boston, Philadelphia, and Liverpool Athenæa, the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the Massachusetts Historical Society for their assistance and for permitting me to quote from unpublished material in their collections. -

City of Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update

2015 City of Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update City of Salem Department of Planning and Community Development Prepared by: Community Opportunities Group, Inc. Unless noted otherwise, all images in this document provided by Patricia Kelleher, Community Opportunities Group, Inc. The Salem Historic Preservation Plan Update has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Secretary of the Commonwealth William Francis Galvin, Chairman. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission. This program received Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office for Equal Opportunity, National Park Service, 1849 C Street NW, Washington, DC 20240. Table of Contents Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter 1 – Historic Overview of Salem ……………………………………………............ 18 Preservation Timeline …………………………………………………………….. 25 Chapter 2 – Salem Today ……………………………………………………………………….. 27 Historic Neighborhoods …………………………………………………………. 29 Historic Resources ………………………………………………………………… 41 Publicly-Owned Historic Resources ……………………………………………. 51 Overview of Previous Planning Studies ………………………………………… 59 Agencies & Organizations Engaged in Preservation Efforts …………………. 65 Chapter 3 - Existing Planning Efforts, Regulations & Policies………………………………. 76 Salem’s Historic Resource Inventory ….………………………………………..