Asher Benjamin As an Architect in Windsor, Vermont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. Classification 4. Owner of Property

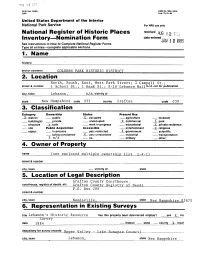

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received mjp Inventory Nomination Form date entered JAN I 0 I985 See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections________________ 1. Name historic and/or common CQLBURN PARK HISTORIC DISTRICT 2. Location North, South, East, West Park Street; 3 Camp ell St.; street & number j School St.; 1 Bank St.; 9-10 Lebanon Mall 11^"0* for publication city, town Lebanon, n/_a_ vicinity of state New Hampshire code 055 county Grafton code 009 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use _JL district public _X_ occupied __ agriculture museum building(s) private unoccupied X commercial X park structure X botn work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment X religious object in process yes: restricted X government scientific being considered JX__ yes: unrestricted industrial transportation X n/a no military other: 4. Owner of Property name (see enclosed multiple ownershi list 1-4-1 street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description Grafton County Courthouse courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Grafton County Registry of Deeds P.O. Box 208 street & number city, town Woodsville, state New Hampshire 05875 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Lebanon* S Historic Resource has this property been determined eligible? yes no Survey date 1984 federal state county X local depository for survey records np p Rr y a i 1py - .qim apee Council city, town Lebanon, state New Hampshire Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered _X_ original site _X- good ruins X altered moved date N/A fair '"-. -

Exploring Boston's Religious History

Exploring Boston’s Religious History It is impossible to understand Boston without knowing something about its religious past. The city was founded in 1630 by settlers from England, Other Historical Destinations in popularly known as Puritans, Downtown Boston who wished to build a model Christian community. Their “city on a hill,” as Governor Old South Church Granary Burying Ground John Winthrop so memorably 645 Boylston Street Tremont Street, next to Park Street put it, was to be an example to On the corner of Dartmouth and Church, all the world. Central to this Boylston Streets Park Street T Stop goal was the establishment of Copley T Stop Burial Site of Samuel Adams and others independent local churches, in which all members had a voice New North Church (Now Saint Copp’s Hill Burying Ground and worship was simple and Stephen’s) Hull Street participatory. These Puritan 140 Hanover Street Haymarket and North Station T Stops religious ideals, which were Boston’s North End Burial Site of the Mathers later embodied in the Congregational churches, Site of Old North Church King’s Chapel Burying Ground shaped Boston’s early patterns (Second Church) Tremont Street, next to King’s Chapel of settlement and government, 2 North Square Government Center T Stop as well as its conflicts and Burial Site of John Cotton, John Winthrop controversies. Not many John Winthrop's Home Site and others original buildings remain, of Near 60 State Street course, but this tour of Boston’s “old downtown” will take you to sites important to the story of American Congregationalists, to their religious neighbors, and to one (617) 523-0470 of the nation’s oldest and most www.CongregationalLibrary.org intriguing cities. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY VOLUME LXV APRIL, 1941 NUMBER TWO Some Qree\T(evival Architects of Philadelphia HILADELPHIA saw alike the birth and the death of Greek Revival architecture in America: its birth in the Bank of Penn- Psylvania, which Latrobe designed in the spring of 17985 its death—or should one say its final swan song?—in the Ridgeway Branch of the Library Company, designed in the 1870's by Addison Hutton, far out on South Broad Street. And, in the years between, several of the most important Greek Revival architects in the coun- try established their homes in Philadelphia, found there a most profitable field for their activity, and designed for it some of the most remarkable of its buildings. Latrobe, Mills, Strickland, Havi- land, and Walter all contributed much to the appearance of the growing city, and in the work of all, whether it was strictly Greek or not, the ideals of the new architectural movement were enshrined. It is not strange that this should have been the case. Philadelphia was, in the early years of the Republic, the undoubted metropolis of the country. It was, in its own characteristic staid way, the center of culture and of art. Boston was still, in architecture, largely under the sway of English late-Georgian inspiration, so beautifully re-created in New England in the domestic work of Bulfinch, the exquisite 121 122 TALBOT HAMLIN April interiors of Mclntire, and the early handbooks of Asher Benjamin. New York, struggling out of the devastation caused by the long British occupation, was still dominated by the transitional work of John McComb, Jr., the Mangins, and such architects as Josiah Brady and the young Martin Thompson; Greek forms were not to become popular there till the later 1820's. -

K:\Fm Andrew\21 to 30\27.Xml

TWENTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1841, TO MARCH 3, 1843 FIRST SESSION—May 31, 1841, to September 13, 1841 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1841, to August 31, 1842 THIRD SESSION—December 5, 1842, to March 3, 1843 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1841, to March 15, 1841 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—JOHN TYLER, 1 of Virginia PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—WILLIAM R. KING, 2 of Alabama; SAMUEL L. SOUTHARD, 3 of New Jersey; WILLIE P. MANGUM, 4 of North Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—ASBURY DICKENS, 5 of North Carolina SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—STEPHEN HAIGHT, of New York; EDWARD DYER, 6 of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—JOHN WHITE, 7 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—HUGH A. GARLAND, of Virginia; MATTHEW ST. CLAIR CLARKE, 8 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—RODERICK DORSEY, of Maryland; ELEAZOR M. TOWNSEND, 9 of Connecticut DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH FOLLANSBEE, of Massachusetts ALABAMA Jabez W. Huntington, Norwich John Macpherson Berrien, Savannah SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE REPRESENTATIVES 12 William R. King, Selma Joseph Trumbull, Hartford Julius C. Alford, Lagrange 10 13 Clement C. Clay, Huntsville William W. Boardman, New Haven Edward J. Black, Jacksonboro Arthur P. Bagby, 11 Tuscaloosa William C. Dawson, 14 Greensboro Thomas W. Williams, New London 15 REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas B. Osborne, Fairfield Walter T. Colquitt, Columbus Reuben Chapman, Somerville Eugenius A. Nisbet, 16 Macon Truman Smith, Litchfield 17 George S. Houston, Athens John H. Brockway, Ellington Mark A. Cooper, Columbus Dixon H. Lewis, Lowndesboro Thomas F. -

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Massachusetts State House AND/OR COMMON Massachusetts State House I LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Beacon Hill —NOT FOR PUBiJCATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Boston . VICINITY OF 8 th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ...DISTRICT X.PUBLIC AOCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM -XBUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL ...PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —.WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL — PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS XYES: RESTRICTED -KGOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC ..BEING CONSIDERED — YES UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL — TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Commonweath of Massachusetts STREETS NUMBER Beacon Street CITY" TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Massachusetts (LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Somerset Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLELE Historic American Buildings Survey (Gates and Steps, 10 sheets, 6 photos) DATE 1938,1941 X FEDERAL —.STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress/Annex Division of Prints and Photographs CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE_____ —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The following description from the Columbian Centinel, January 10, 1798 is reproduced in Harold Kinken's The Architecture of Charles Bulfinch, The New State-House is an oblong building, 173 feet front, and 61 deep, it consists externally of a basement story, 20 feet high, and a principal story 30 feet. -

Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy In Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy, Erik J. Engstrom offers an important, historically grounded perspective on the stakes of congressional redistricting by evaluating the impact of gerrymandering on elections and on party control of the U.S. national government from 1789 through the reapportionment revolution of the 1960s. In this era before the courts supervised redistricting, state parties enjoyed wide discretion with regard to the timing and structure of their districting choices. Although Congress occasionally added language to federal- apportionment acts requiring equally populous districts, there is little evidence this legislation was enforced. Essentially, states could redistrict largely whenever and however they wanted, and so, not surpris- ingly, political considerations dominated the process. Engstrom employs the abundant cross- sectional and temporal varia- tion in redistricting plans and their electoral results from all the states— throughout U.S. history— in order to investigate the causes and con- sequences of partisan redistricting. His analysis -

The East India Marine Society's

Global Knowledge in the Early Republic The East India Marine Society’s “Curiosities” Museum Patricia Johnston On a cold January day in 1804, the Reverend William Bentley, pastor of the East Church, stood and watched a strange and exotic parade weaving through the streets of Salem, Massachusetts. A number of sea captains, who had just returned from Sumatra, Bombay, Calcutta, Canton, Manila, and other Asian ports, put on this public display to commemorate their recent business adventures. Bentley recorded in his diary, “This day is the Annual Meeting of the East India Marine Society. After business & before din- ner they moved in procession, . Each of the brethren bore some Indian curiosity & the palanquin was borne by the negroes dressed nearly in the Indian manner. A person dressed in Chinese habits & mask passed in front. The crowd of spectators was great.”1 The objects that the minister described demonstrate the global circula- tion of material culture in the Early Republic. Waiting in Asian harbors for trade opportunities, captains and crews swapped souvenirs that had literally circled the world. When they returned to their hometowns, they shared the objects they collected, both privately with acquaintances and publicly in mu- seums and parades that were widely covered in the newspapers. These global artifacts provide insights into the broad intellectual pursuits of the Early Republic, including natural history, ethnography, and aesthetics. The objects also illuminate early trade relations and cultural perceptions between Asia and the new United States. When displayed back in the United States, artifacts helped construct and reinforce social hierarchies in American seaports; they also expressed America’s arrival as a full participant in world commerce. -

A Pictoral History of the Boston Music Hall and the Great Organ

A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF THE BOSTON MUSIC HALL AND THE GREAT ORGAN by Ed Sampson, President, Methuen Memorial Music Hall, Inc. 2018 Few instruments in the history of pipe organs in America have had as long, or as distinguished, a career as the Boston Music Hall Organ. The first concert organ in the country, it remains today one of the outstanding organs in America. The need for a large and centrally-located concert hall for Boston was discussed at the annual meeting of the Harvard Musical Association, founded in 1837 (Henry White Pickering (1811-1898), President) on January 31, 1851. A "Music Hall Committee", comprised of members Robert East Apthorp (1812-1882), George Derby (1819-1874), John Sullivan Dwight (1813-1893), Charles Callahan Perkins (1822-1886), and Dr. Jabez Baxter Upham (1820- 1902), was appointed to address the matter. The Boston Music Hall was built in 1852 by the Boston Music-Hall Association, founded in 1851 (Jabez Baxter Upham, President) and by the Harvard Musical Association, that contributed $100,000 towards its construction. It stood in the center of a block that sloped downward from Tremont Street to Washington Street; and was between Winter Street on the south and Bromfield Street on the north. Almost entirely surrounded by other buildings, only glimpses of the hall's massive granite block foundation and plain brick walls could be seen. There were two entrances to the Music Hall: the Bumstead Place entrance, (named after Thomas Bumstead (1740-1828) a Boston coachmaker), off Tremont Street (later Hamilton Place) opposite the Park Street Church; 1 and the Central Place or Winter Place (later Music Hall Place) entrance off Winter Street. -

John Winthrop (1587/88-1649), 1798 Samuel Mcintire (1757-1811

John Winthrop (1587/88-1649), 1798 Samuel McIntire (1757-1811) carved and painted wood 15 1/2 (h) (39.370) inscribed on the base: "Winthrop” Bequest of William Bentley, 1819 Weis 149 Hewes number: 155 Ex. Coll.: commissioned by the donor, 1798. Exhibitions: 1804, Independence Day Celebration, Salem Meeting House. 1931, "American Folk Sculpture," Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey. 1957, "Samuel McIntire," Essex Institute, no. 8. 1977, "Landscape and Faction: Spatial Transformation in William Bentley's Salem," Essex Institute, no. 18. Publications: "Editor's Attic," The Magazine Antiques 21(January 1932): 8, 12. "Editor's Attic," The Magazine Antiques 28(October 1935): 138-40. Fiske Kimball, Mr. Samuel McIntire, Carver, The Architect of Salem (Portland, Maine: Southworth-Anthoensen Press, 1940): 138, fig. 362. Nina Fletcher Little, "Carved Figures by Samuel McIntire and his Contemporaries," Essex Institute Historical Collections 93(April-July 1957): 195-96, fig. 48. Susan Geib, "Landscape and Faction: Spatial Transformation in William Bentley's Salem," Essex Institute Historical Collections 113(July 1977): 217. This bust of John Winthrop was carved nearly one hundred and fifty years after the governor's death. It was commissioned by the Salem minister William Bentley (cat. #8) in 1798 as an addition to his "cabinet" of portraits of famous Massachusetts politicians and ministers. Bentley owned a painted miniature of the governor (cat. #154) that had been copied from a large seventeenth century canvas (cat. #153). Bentley loaned this miniature to the carver, Samuel McIntire, for the artist to use as reference for the carving. Bentley was familiar with the carver and his work. -

The Old Capitol As Completed

CHAPTER VI THE OLD CAPITOL AS COMPLETED 1 HE old Capitol was situated in a park of 22 ⁄2 acres [Plate 87], The eastern entrance, according to Mills, had spacious gravel inclosed by an iron railing.1 There were nine entrances to the walks, through a “dense verdant inclosure of beautiful shrubs and trees, grounds, two each from the north and south for carriages, two circumscribed by an iron palisade.” 3 An old print, made from a draw- on the east and three on the west for pedestrians. The western ing by Wm. A. Pratt, a rural architect and surveyor in 1839, gives a Tentrances at the foot of the hill were flanked by two ornamental gate or clear idea of the eastern front of the building and its surroundings at watch houses [Plate 81]. The fence was of iron, taller than the head of this period [Plate 90]. an ordinary man, firmly set in an Aquia Creek sandstone coping, which The old Capitol building covered 67,220 square feet of ground. covered a low wall [Plate 82]. The front was 351 feet 4 inches long. The depth of the wings was 131 On entering the grounds by the western gates, passing by a foun- feet 6 inches; the central eastern projection, including the steps, 86 feet; tain, one ascended two flights of steps to the “Grand Terrace” [Plate 88]. the western projection, 83 feet; the height of wings to the top of Upon the first terrace was the Naval Monument, erected to those balustrade, 70 feet; to top of Dome in center, 145 feet. -

Italy Under the Golden Dome

Italy Under the Golden Dome The Italian-American Presence at the Massachusetts State House Italy Under the Golden Dome The Italian-American Presence at the Massachusetts State House Susan Greendyke Lachevre Art Collections Manager, Commonwealth of Massachusetts Art Commission, with the assistance of Teresa F. Mazzulli, Doric Docents, Inc. for the Italian-American Heritage Month Committee All photographs courtesy Massachusetts Art Commission. Fifth ed., © 2008 Docents R IL CONSOLE GENERALE D’ITALIA BOSTON On the occasion of the latest edition of the booklet “Italy Under the Golden Dome,” I would like to congratulate the October Italian Heritage Month Committee for making it available, once again, to all those interested to learn about the wonderful contributions that Italian artists have made to the State House of Massachusetts. In this regard I would also like to avail myself of this opportunity, if I may, to commend the Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the Hon. William F. Galvin, for the cooperation that he has graciously extended to the Committee in this particular endeavor. Italians and Italian Americans are rightly proud of the many extraordinary works of art that decorate the State House, works that are either made by Italian artists or inspired by the Italian tradition in the field of art and architecture. It is therefore particularly fitting that the October Italian Heritage Month Committee has taken upon itself the task of celebrating this unique contribution that Italians have made to the history of Massachusetts. Consul General of Italy, Boston OCTOBER IS ITALIAN-AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH On behalf of the Committee to Observe October as Italian-American Heritage Month, we are pleased and honored that Secretary William Galvin, in cooperation with the Massachusetts Art Commission and the Doric Docents of the Massachusetts State House, has agreed to publish this edition of the Guide. -

Charles Bulfinch's Popularity Flourished in the 1790'S After Articles

Charles Bulfinch's popularity flour ished in the 1790's after articles and images of the Ho llis Street Church, his first major project, were publ ished . The images led lo two ear ly church commissions ou tside of Boston an d signaled the beginning ofBu lfinch 's growing inlluence on New England ch urch architecture. The church comm issions also led to a wide variety of requests for Bulfinch designed institu tional buildings. such as court houses. banks and collegiate arch itecture, as well as designs for private mansions, evidence of which can be found in Salem, Massachusells and Maine. Bulfinch's chu rch designs had several innovat ive elements . Traditiona lly, lhe entrances lo a New England sty le meeting houses, where relig ious and public meetings were held, had been placed on the short ax is of the building where members entered from the sides. Bulfinch reorganized this design along the lines of a classical Latinate plan, placing the entrance on the long ax is at the front of the church and pulpit at the far end. He also brough t the free sta nding tower and steeple back into the body of the bui lding, above the entrance w ith a pedimen t porch to suppor t it. The two churches which began this trend were the Congregat ional Churches in Pittsfield (1793) an d Taunton (1792), very sim ilar in design, and wide ly copied thro ughout the New Englan d area . Other churches Bulfinch worked on outside of Boston were the Old South Church in Hallowell, Maine, where he designed the Cupola (1806), and the Church of Chris t in Lancaster, Massachusetts .