Collections of the Original Library of Allegheny College, 1819-1823

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the College

History of the College A liberal arts education in colonial America was a privilege enjoyed by few individuals. The nine colleges that existed pri- or to the American Revolution did not mean to be popular institutions. But the Revolution altered this state of affairs, and as the floodgates opened to the rising democratic tide, numerous colleges and universities were chartered in the young republic. The westward movement, growing populations, increasing wealth, state loyalties, and denominational rivalries all played a part in the early expansion of American higher education. Perhaps as many as 100 colleges tried and failed before the Civil War. Allegheny, founded in 1815, is one of the hardy survivors that testifies daily to the pioneer determination and vision of higher education in America. Foundation and Early Years the contributions that Alden had collected in the East. Allegheny is situated in Meadville, Pennsylvania, which was founded in Despite such generous gifts, however, the first years were difficult 1788 in the French Creek Valley, astride the route traversed by George ones. Both students and funds remained in short supply, and in vain Washington on his journey to Fort LeBoeuf a generation earlier. When the trustees turned for support to the Legislature of Pennsylvania and the College was established, Meadville was still a raw frontier town of the Presbyterian Church, of which Alden was a minister. Over Alden’s about 400 settlers, of whom an unusually large number had come from vigorous protests in the name of a classical liberal arts curriculum, the Massachusetts and Connecticut. These pioneers had visions of great trustees even entertained a proposal to turn the College into a military things for their isolated village, but none required greater imagination academy in order to attract support. -

The East India Marine Society's

Global Knowledge in the Early Republic The East India Marine Society’s “Curiosities” Museum Patricia Johnston On a cold January day in 1804, the Reverend William Bentley, pastor of the East Church, stood and watched a strange and exotic parade weaving through the streets of Salem, Massachusetts. A number of sea captains, who had just returned from Sumatra, Bombay, Calcutta, Canton, Manila, and other Asian ports, put on this public display to commemorate their recent business adventures. Bentley recorded in his diary, “This day is the Annual Meeting of the East India Marine Society. After business & before din- ner they moved in procession, . Each of the brethren bore some Indian curiosity & the palanquin was borne by the negroes dressed nearly in the Indian manner. A person dressed in Chinese habits & mask passed in front. The crowd of spectators was great.”1 The objects that the minister described demonstrate the global circula- tion of material culture in the Early Republic. Waiting in Asian harbors for trade opportunities, captains and crews swapped souvenirs that had literally circled the world. When they returned to their hometowns, they shared the objects they collected, both privately with acquaintances and publicly in mu- seums and parades that were widely covered in the newspapers. These global artifacts provide insights into the broad intellectual pursuits of the Early Republic, including natural history, ethnography, and aesthetics. The objects also illuminate early trade relations and cultural perceptions between Asia and the new United States. When displayed back in the United States, artifacts helped construct and reinforce social hierarchies in American seaports; they also expressed America’s arrival as a full participant in world commerce. -

Federalist Politics and the Unitarian Controversy Marc M

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship Winter 2002 The orF ce of Ancient Manners: Federalist Politics and the Unitarian Controversy Marc M. Arkin Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Marc M. Arkin, The Force of Ancient Manners: Federalist Politics and the Unitarian Controversy, 22 J. of the Early Republic 575 (2002) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/716 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORCE OF ANCIENT MANNERS: FEDERALIST POLITICS AND THE UNITARIAN CONTROVERSY REVISITED Marc M. Arkin Some of our mutual friends say all is lost-nothing can be done. Nothing is to be done rashly, but mature counsels and united efforts are necessary in the most forlorn case. For though we may not do much to save ourselves, the vicissitudes of political fortune may do every thing-and we ought to be ready when she smiles.1 As 1804 drew to a close, Massachusetts Federalists could be forgiven for thinking that it had been a very bad year, the latest among many. -

Prominent Journalist Rebuilt Stone M. E. Church Was

EXAMS IN 4 WEEKS THE CAMPUS EXAMS IN 4 WEEKS OF ALLEGHENY COLLEGE VOL. XLVI, NO. 23 MEADVILLE, PENNSYLVANIA MAY 2, 1928 PROMINENT JOURNALIST REBUILT STONE M. E. CHURCH WAS TENTATIVE SCHEDULE JOHN ARTHUR 6IBSON ALUMNUS OF ALLEfillENY DEDICATED LAST SUNDAY MORNING FOR EXAMS ANNOUNCED IS NOMINATED AGAIN STARTED NEWSPAPER WORK AS STUDENTS MUST REPORT ALL ALUMNI TRUSTEE NAMED FOR COMPETITOR ON STAFF CONFLICTS TO OFFICE FOURTH TERM IN OF "THE CAMPUS" AT ONCE THAT OFFICE Monday, May 28 John Arthur Gibson '91, Superintend- 'William Preston Beazell '97, nomi- nated for Alumni Trusteeship, has a A. M. P. M. ent of the Butler Public Schools, was threefold tie with Allegheny, for his Biology II Biology III recently nominated to serve a fourth father was Benjamin F. Beazell, D. D. Economics I Biology IV term as Alumni Trustee by the Alumni '68, and his wife, Isabel Howe '96. Al- Education III English Lang. V of his district. His ceaseless inter- though he did not come to Allegheny English Lit. IX English Lit. II est in the betterment of Allegheny until his junior year he was actively French VII French VI College has gained for him wide popu- identified with college affairs from the Latin I Geology I larity, and this recent honor conferred time of his arrival. He was a member Physics V Mathematics IM upon him by his contingent, is a dem- of Phi Delta Theta, on the editorial Pol. Science H onstration of the trust and confidence placed in him. An educator of note boards of both the Campus and the Tuesday, May 29 since his graduation, he has taken an Kaldron, president of the Oratorical Biology V Philosophy II active part in the progress of the But- Association and a member of the first Chemistry III Philosophy Hi ler Public School system. -

View of John Winthrop's Career As a Scientist, to Mention the Copy of Euclid, Cambridge, 1655, Which Had Been Used in College Successively by Penn Townsend (A.B

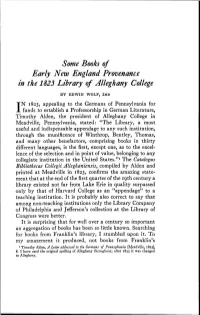

Some Books of Early New England Provenance in the 1823 Library of Alleghany College BY EDWIN WOLF, 2ND N 1823, appealing to the Germans of Pennsylvania for I funds to establish a Professorship in German Literature, Timothy Alden, the president of Alleghany College in Meadville, Pennsylvania, stated: "The Library, a most useful and indispensable appendage to any such institution, through the munificence of Winthrop, Bentley, Thomas, and many other benefactors, comprising books in thirty different languages, is the first, except one, as to the excel- lence of the selection and in point of value, belonging to any collegiate institution in the United States."' The Catalogus Bibliothecae Collegii Alleghaniensis, compiled by Alden and printed at Meadville in 1823, confirms the amazing state- ment that at the end of the first quarter of the 19th century a library existed not far from Lake Erie in quality surpassed only by that of Harvard College as an "appendage" to a teaching institution. It is probably also correct to say that among non-teaching institutions only the Library Company of Philadelphia and Jefferson's collection at the Library of Congress were better. It is surprising that for well over a century so important an aggregation of books has been so little known. Searching for books from Franklin's library, I stumbled upon it. To my amazement it produced, not books from Franklin's ' Timothy Alden, A Letter addressed to the Germans of Pennsylvania [Meadville, 1823], 8. I have used the original spelling of Alleghany throughout; after 1833 it was changed to Allegheny. 14 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [April, library, but a wealth of New England provenance. -

William Bentley

WILLIAM BENTLEY (1759-1819), before 1826 James Frothingham (1786-1864) copy after his own composition oil on canvas 27 1/4 x 22 1/4 (69.22 x 56.50) Bequest of Hannah Armstrong Kittredge, 1917 Weis 10 Hewes Number: 8 Ex. Coll.: Possibly commissioned by Hannah Pippen Hodges (1768-1837); to her daughter Hannah Hodges Kittredge (1793-1877); to her daughter, the donor (1834-1916). Exhibitions: ‘Dr. Bentley’s Salem: Diary of a Town,’ Essex Institute, Salem, Mass., 1977. Publications: ‘Dr. Bentley’s Salem: Diary of a Town,’ Historical Collections of the Essex Institute 113 (July 1977): 34. Stefanie Munsing Winkelbauer, ‘William Bentley: Connoisseur and Print Collector,’ in Georgia B. Barnhill, ed., Prints of New England (Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1991), 22. The Reverend William Bentley was a noted bibliophile, scholar, historian, and linguist. He was the minister of the East Church (Unitarian) in Salem, Massachusetts, from 1783 to his death in 1819. In his remarkable diaries, the manuscripts of which are preserved at the American Antiquarian Society, Bentley recorded local and national events, shipping news, church business, scientific theories, and town gossip.1 He can be considered Salem’s first archivist, recording scraps of genealogical information and town history in his diary. He also commissioned several portraits of prominent New England leaders, most of which were copied after well-known canvases, and placed these replicas in his ‘cabinet.’ Bentley graduated from Harvard College in 1777 and, with a talent for languages, tutored Greek and Latin there while looking for a church position. After moving to Salem, Bentley began to contribute political and social commentary to the Salem Register. -

Lindsley Family Genealogical Collection, 1784-2016

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives Lindsley Family Genealogical Collection, 1784-2016 COLLECTION SUMMARY Creator: Rose, Stanley Frazer Inclusive Dates: 1784-2016, bulk 1850-1920 Scope & Content: Consists of genealogical research relating to the Lindsley family and its related branches. These records primarily contain photocopied research relating to the history of these families. There are two folders in Box 1 that hold information regarding Berrien family membership in the Society of the Cincinnati. Rose also compiled detailed genealogy trees and booklets for all of the family branches. This collection was kept in the original order in which it was donated. The compiler also created the folder titles. Physical Description/Extent: 6 cubic feet Accession/Record Group Number: 2016-028 Language: English Permanent Location: XV-E-5-6 1 Repository: Tennessee State Library and Archives, 403 Seventh Avenue North, Nashville, Tennessee, 37243-0312 Administrative/Biographical History Stanley Frazer Rose is a third great grandson Rev. Philip Lindsley (1786-1855). He received his law degree and master’s degree in management from Vanderbilt University. Organization/Arrangement of Materials Collection is loosely organized and retains the order in which it was received. Conditions of Access and Use Restrictions on Access: No restrictions. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction: While the Tennessee State Library and Archives houses an item, it does not necessarily hold the copyright on the item, nor may it be able to determine if the item is still protected under current copyright law. Users are solely responsible for determining the existence of such instances and for obtaining any other permissions and paying associated fees that may be necessary for the intended use. -

John and Priscilla Alden Family Sites

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ALDEN, JOHN AND PRISCILLA, FAMILY SITES Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Alden, John and Priscilla, Family Sites Other Name/Site Number: Alden House (DUX.38) and Original Alden Homestead Site (aka Alden I Site, DUX-HA-3) 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 105 Alden Street Not for publication: City/Town: Duxbury Vicinity: State: Massachusetts County: Plymouth Code: 023 Zip Code: 02331 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _X Public-Local: X District: __ Public-State: Site: _X Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 3 buildings 1 sites structures _ 1 objects 2 4 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Original Alden Homestead NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ALDEN, JOHN AND PRISCILLA, FAMILY SITES Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Boston Public

BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY FORM NO =k== J^l n^ [J1 c^9G"^l\.J\%l^(»7 PURCHASED FROM lr ^ titui'la OP THE DESCENDANTS OF THE HON. JOHN ALDEN. BY EBENEZER ALDEN, M. D.. HEMBBR OF THB AMKRIOAN ANTIQUARIAN BOOIETT, NEW ENGLAND HISTORIC GENEALOGICAL SOCIETYi AC. 3 3 > J i i > > > \ , )>,->5j':>>J> ' ^ " ' ; > . 1 > > J RANDOLPH, MASS, PRINlTED BY SAMUEL P. BROWN. FOR THE FAMILY. 1867. Xy ^,CS7/ ^ Cjc^^^ ^ / {>" • ••« i • • • • • • • • * • • • •*. •*: • • .. t . • .• ••• I :••• \ i I 'c INTRODUCTIONS'. is to a Genealogy fiimily history ; some chaos of isolated facts to facts ; very dry; others, revealing prin- ciples, laws, methods of the divine government. has its lessons for such as will them Genealogy study ; uses for such as can appreciate and interpret them. The family precedes the state. Love of kindred under- lies true patriotism. Hon. John Alden was one of the principal persons, and the last male survivor of the band of Pilgrims, who came to Plymouth in the May Flower in 1620. With few exceptions, and these mostly of recent date, all persons in this country bearing the name of Alden are his descendents. Of each of these who is at the head of a family, it is the plan of this work to give, as far as the facts are at hand, the name, residence, occupation of males over twenty-one years of age, date of birth, and, if deceased, of death, parentage and social position. Descendents of the common ancestor bearing other names are noticed in connection with the families from which they originated. Families are usually numbered consecutively. -

The Pickering Genealogy

til £ % » ft'J^. • » in s L»^ • ea K • • 'ssvh *Marivs xv asnoH ONraasDid hhx THE PICKERING GENEALOGY: BEING AN ACCOUNT OF THE fixxt Ct>ro Generations OF THE PICKERING FAMILY OF SALEM, MASS., AND OF THE DESCENDANTS OP JOHN AND SARAH (BURRILL) PICKERING, OF THE THIRD GENERATION. BY HARRISON ELLERY \\ AND CHARLES PICKERING BOWDITCH. Vol. I. Pages 1-287. PRIVATELY PRINTED. 1897. C-flUy^^ TWO COPIES REGf?f?3 Copyright, 1897, Bt Chaeles P. Bowditch. ONE HUNDEBD COPIES PEINTED. Univbbbitt Press : Jomr WiuoH and Son, Cambridge, U.S. A. PREFACE. 1887 Ipublished, under the title of "The Pickering Genealogy, IN comprising the descendants of John and Sarah (Burrill)Pickering, of Salem," seventy sheets which contained the names and dates of the Sarah birth, death, and marriage of the descendants of John and Pickering, and of their husbands and wives, as far as they had been ascertained. Istated in the preface of the index to that publication— that the general plan of "The Pickering Genealogy" was: volume is First. To print in the form of sheets (I*6 those to wbich this of the first JOHN an index) as complete a list as possible of the descendants female as fully PICKERING, who came to Salem about 1636, tracing out the as the male descent. on sheets, and giving, Second. To issue a book, referring to the names the names are there recorded, as far as practicable, sketches of the individuals whose families, length of life, birth of with statistical information as to the size of generations. twins, preponderance of male or female children, etc., in the different additional sheets, the Third. -

T^Ie Ffrsf Page of Timothy Alden's Catalogus Bibliothecae Collegii

T^ie ffrsf page of Timothy Alden's Catalogus Bibliothecae Collegii Alleghaniensis, 1823 (from the archives of the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania) Icons of Learning: William Bentley's Library and Allegheny College Bruce M. Stephens 1823, a lengthy pamphlet entitled Catalogus Bibliothecae Collegii Alleghaniensis, compiled by the Reverend Timothy Alden, INissued from the press of Thomas Atkinson of Meadville, Pennsyl- vania. The Reverend Mr. Alden, first president of Allegheny College in Meadville, proclaimed boldly in the same year that his institution's library was "the first, except one, as to the excellence of the selection and in point of value, belonging to any collegiate institution in the United States." lThat Alden's claim was not mere institutional one- upmanship has been substantiated by a distinguished modern bibli- ographer who notes that "inaddition to Harvard, itis probably also correct to say that among non-teaching institutions only the Library Company of Philadelphia and Jefferson's collection at the Library of Congress were better." 2 This is rather remarkable company for a small, struggling liberal arts college, and the question is thus :how did one of the most important library collections in America, and such a sizeable cultural inheritance of New England, come into the possession of a frontier outpost of learning early inthe nineteenth century? The donation of his library by the Reverend William Bentley (1759-1819) to Allegheny College is something more than a case of nineteenth-century philanthropy. It is an indication of the cultural hopes and intellectual aspirations of this Unitarian clergyman and his vision of the new nation. -

THE COURTSHIP of MILES STANDISH by Frances D

LOVE & LEGEND: THE COURTSHIP OF MILES STANDISH by Frances D. Leach In The Courtship of Miles Standish, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow immortalized the legend of the love triangle between John Alden, Miles Standish, and Priscilla Mullins. Longfellow, an Alden descendant, wove the narrative around an old family tradition. The earliest time the story appears in print is in Timothy Alden’s A Collection of American Epitaphs and Inscriptions with Occasional Notes, published in 1814. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) was a scholar, a Harvard professor, and a poet. His poems were immensely popular both at home and abroad. He provided the Victorians with poetry, drama and romance -- enabling them to escape the drab cities of the Industrial Revolution or the loneliness of the isolated farmhouse. Longfellow’s vivid verbal imagery, wrapped in the gentle cadences of his verse, bring each scene to life. His narrative poems include Evangeline (1847), Hiawatha (1855), and The Courtship of Miles Standish (1858). Generations of schoolchildren grew up with Longfellow’s poetry. In The Courtship of Miles Standish, they discovered an exciting human dimension in the textbook story of the Pilgrims. It is evident that the poet had access to historical records, but he did not feel constrained to follow the literal course of events. For dramatic effect, he compressed several years of incidents into a very short time frame in 1621. Longfellow used his imagination to flesh out the characters in his love triangle. Miles Standish appears as a swash-buckling hero, brave but inarticulate and somewhat peevish. Handsome young John Alden is torn between his devotion to the Captain and his love for the Pilgrim maiden.