A Comprehensive Study of Evolution of Domes in Indo- Islamic Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Door/Window Sensor DMWD1

Always Connected. Always Covered. Door/Window Sensor DMWD1 User Manual Preface As this is the full User Manual, a working knowledge of Z-Wave automation terminology and concepts will be assumed. If you are a basic user, please visit www.domeha.com for instructions. This manual will provide in-depth technical information about the Door/Window Sensor, especially in regards to its compli- ance to the Z-Wave standard (such as compatible Command Classes, Associa- tion Group capabilities, special features, and other information) that will help you maximize the utility of this product in your system. Door/Window Sensor Advanced User Manual Page 2 Preface Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................. 2 Description & Features ..................................................................................................... 4 Specifications ..................................................................................................................... 5 Physical Characteristics ................................................................................................... 6 Inclusion & Exclusion ........................................................................................................ 7 Factory Reset & Misc. Functions ..................................................................................... 8 Physical Installation ......................................................................................................... -

Advancements in Arch Analysis and Design During the Age of Enlightenment

ADVANCEMENTS IN ARCH ANALYSIS AND DESIGN DURING THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT by EMILY GARRISON B.S., Kansas State University, 2016 A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Architectural Engineering and Construction Science and Management College of Engineering KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2016 Approved by: Major Professor Kimberly Waggle Kramer, PE, SE Copyright Emily Garrison 2016. Abstract Prior to the Age of Enlightenment, arches were designed by empirical rules based off of previous successes or failures. The Age of Enlightenment brought about the emergence of statics and mechanics, which scholars promptly applied to masonry arch analysis and design. Masonry was assumed to be infinitely strong, so the scholars concerned themselves mainly with arch stability. Early Age of Enlightenment scholars defined the path of the compression force in the arch, or the shape of the true arch, as a catenary, while most scholars studying arches used statics with some mechanics to idealize the behavior of arches. These scholars can be broken into two categories, those who neglected friction and those who included it. The scholars of the first half of the 18th century understood the presence of friction, but it was not able to be quantified until the second half of the century. The advancements made during the Age of Enlightenment were the foundation for structural engineering as it is known today. The statics and mechanics used by the 17th and 18th century scholars are the same used by structural engineers today with changes only in the assumptions made in order to idealize an arch. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series ARC2013-0723

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2013-0723 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series ARC2013-0723 Reuse of Historical Train Station Buildings: Examples from the World and Turkey H.Abdullah Erdogan Research Assistant Selcuk University Faculty of Architecture Department of Architecture Turkey Ebru Erdogan Assistant Professor Selcuk University Faculty of Fine Arts Department of Interior Architecture & Environmental Design Turkey 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2013-0723 Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN 2241-2891 7/11/2013 2 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2013-0723 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. The papers published in the series have not been refereed and are published as they were submitted by the author. The series serves two purposes. First, we want to disseminate the information as fast as possible. Second, by doing so, the authors can receive comments useful to revise their papers before they are considered for publication in one of ATINER's books, following our standard procedures of a blind review. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

The Story of Architecture

A/ft CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY FINE ARTS LIBRARY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 062 545 193 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1992. Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924062545193 o o I I < y 5 o < A. O u < 3 w s H > ua: S O Q J H HE STORY OF ARCHITECTURE: AN OUTLINE OF THE STYLES IN T ALL COUNTRIES • « « * BY CHARLES THOMPSON MATHEWS, M. A. FELLOW OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS AUTHOR OF THE RENAISSANCE UNDER THE VALOIS NEW YORK D. APPLETON AND COMPANY 1896 Copyright, 1896, By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY. INTRODUCTORY. Architecture, like philosophy, dates from the morning of the mind's history. Primitive man found Nature beautiful to look at, wet and uncomfortable to live in; a shelter became the first desideratum; and hence arose " the most useful of the fine arts, and the finest of the useful arts." Its history, however, does not begin until the thought of beauty had insinuated itself into the mind of the builder. -

Islamic Domes of Crossed-Arches: Origin, Geometry and Structural Behavior

Islamic domes of crossed-arches: Origin, geometry and structural behavior P. Fuentes and S. Huerta Polytechnic University of Madrid, Spain ABSTRACT: Crossed-arch domes are one of the earliest types of ribbed vaults. In them the ribs are intertwined forming polygons. The earliest known vaults of this type are found in the Great Mosque of Córdoba in Spain built in the mid 10th century, though the type appeared later in places as far as Armenia or Persia. This has generated a debate on their possible origin; a historical outline is given and the different hypotheses are discussed. Geometry is a fundamental part and the different patterns are examined. Though geometry has been thoroughly studied in Hispanic-Muslim decoration, the geometry of domes has very rarely been considered. The geometrical patterns in plan will be examined and afterwards, the geometric problems of passing from the plan to the three-dimensional space will be considered. Finally, a discussion about the possible structural behaviour of these domes is sketched. Crossed-arch domes are a singular type of ribbed vaults. Their characteristic feature is that the ribs that form the vault are intertwined, forming polygons or stars, leaving an empty space in the centre. The fact that the earliest known vaults of this type are found in the Great Mosque of Córdoba, built in the mid 10th century, has generated a debate on their possible origin. The thesis that appears to have most support is that of the eastern origin. This article describes the different hypothesis, to then proceed with a discussion of the geometry. -

Dome Construction

DOME CONSTRUCTION For further information on dome construction Application of Domes: Blue mosque, XVIth century – Istanbul, Turkey Please contact: ( Æ 23.50 m, 43 m high) n Plain masonry built with blocks or bricks n Floors for multi-storey buildings, they can be leveled flat n Roofs, they can be left like that and they will be waterproofed UNITED NATIONS CENTRE n Earthquakes zones, they can be used with a reinforced ringbeam FOR HUMAN SETTLEMENTS They are Built Free Spanning: (UNCHS - HABITAT) n It means that they are built without form n This way is also called the Nubian technique PO Box 30030, Nairobi, KENYA Timber Saving: Phone: (254-2) 621234 n Domes are built with bricks and blocks (rarely with stones) Fax: (254-2) 624265 Variety of Plans and Shapes: E-mail: [email protected] Treasure of Atreus – Tomb of Agamemnon (Æ +/- 18m) n Domes can be built on round, square, rectangular rooms, etc. Mycene, Greece (+/- 1500 BC) n They allow a wider variety of shapes than vaults AUROVILLE BUILDING CENTRE Stability Study: (AVBC / EARTH UNIT) n The shape of a dome is crucial for stability, and a stability study is Office, often needed. Be careful, a wrong shape will collapse Auroshilpam, Auroville - 605 101 Dhyanalingam Temple – Coimbatore, India Auroville, India elliptical section ( Æ 22.16 m, 9.85 m high) (3.63 m side, Need of Skilled Masons: Tamil Nadu, INDIA 0.60 m rise) n Building a dome requires trained masons. Never improvise when Phone: +91 (0)413-622277 / 622168 building domes, ask advice from skilled people Fax: +91 (0)413-622057 -

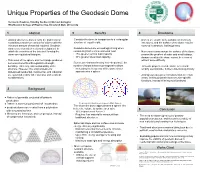

Unique Properties of the Geodesic Dome High

Printing: This poster is 48” wide by 36” Unique Properties of the Geodesic Dome high. It’s designed to be printed on a large-format printer. Verlaunte Hawkins, Timothy Szeltner || Michael Gallagher Washkewicz College of Engineering, Cleveland State University Customizing the Content: 1 Abstract 3 Benefits 4 Drawbacks The placeholders in this poster are • Among structures, domes carry the distinction of • Consider the dome in comparison to a rectangular • Domes are unable to be partitioned effectively containing a maximum amount of volume with the structure of equal height: into rooms, and the surface of the dome may be formatted for you. Type in the minimum amount of material required. Geodesic covered in windows, limiting privacy placeholders to add text, or click domes are a twentieth century development, in • Geodesic domes are exceedingly strong when which the members of the thin shell forming the considering both vertical and wind load • Numerous seams across the surface of the dome an icon to add a table, chart, dome are equilateral triangles. • 25% greater vertical load capacity present the problem of water and wind leakage; SmartArt graphic, picture or • 34% greater shear load capacity dampness within the dome cannot be removed • This union of the sphere and the triangle produces without some difficulty multimedia file. numerous benefits with regards to strength, • Domes are characterized by their “frequency”, the durability, efficiency, and sustainability of the number of struts between pentagonal sections • Acoustic properties of the dome reflect and To add or remove bullet points structure. However, the original desire for • Increasing the frequency of the dome closer amplify sound inside, further undermining privacy from text, click the Bullets button widespread residential, commercial, and industrial approximates a sphere use was hindered by other practical and aesthetic • Zoning laws may prevent construction in certain on the Home tab. -

Chinese Funerary Ceramics

Harn Museum of Art Educator Resources Chinese Funerary Ceramics Large Painted Jar (hu) China Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) Earthenware with pigment 15 3/16 x 11 1/8 in. Harn Museum Collection, 1996.23, Museum purchase, gift of Dr. and Mrs. David A. Cofrin Ceramics have been an integral part of Chinese culture throughout its history. How they were fashioned, decorated and used reflected functional needs, cultural practices and spiritual beliefs. High quality ceramic vessels were created as early as the Neolithic period. By the time of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E. - 220 C.E.), ceramics took many forms, from various types of vessels to figurative work. Surface decoration could take the form of relief, incision, painting, or glazing. Vessels were wheel- thrown, indicating high technical achievement. Many ceramic forms, it seems evident, were modeled on costlier metal prototypes. While ceramics undoubtedly served utilitarian functions, they were also used as funerary objects. During the Han dynasty, the Chinese often buried their dead with objects they would need in the afterlife. This ceramic jar was made for that purpose. Its painted design is intended to resemble lacquer, an extremely valuable material that was considered a sign of high status. Because it was prohibitively expensive for most families to bury the dead with actual lacquer vessels, ceramic replicas were used instead as a way of conserving financial resources for the living. The form and decoration of this jar are perfectly balanced. The painted decoration is intricate and expertly applied. The major theme, seen in the central band, is that of a dragon and a phoenix. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-64441-0 - The Roman Imperial Mausoleum in Late Antiquity Mark J. Johnson Excerpt More information Introduction Of all the building projects undertaken by Roman emperors during the course of their individual reigns, none elicited more personal interest than their own funerary monuments. In the later Roman Empire, as it had been earlier, these were buildings destined to provide a secure resting place for their mortal remains and a site of cult practices. The monuments were meant to project an image of majesty and importance for all others to see, for these were, in fact, sepulcra divorum, tombs of the divi, or demigods, an honor reserved for emperors. The mausolea of the emperors and members of their families thus constitute one of the most conspicuous groups of buildings in late Roman and Early Christian architecture, some of which are well-preserved, whereas others are now in ruins or known solely from literary sources. These monuments are among the period’s most important examples of funerary architecture, a form that was as innovative and varied as it was ubiquitous in the empire. Previous to the present study, these buildings have never been examined as a group, with two exceptions – a brief article that consisted of little more than an annotated list of monuments, and a slim volume that provides an overview of Roman imperial funerals and monuments.1 Some of the individual mausolea have been the subjects of comprehensive monographs, especially in recent years, though others have been treated only in short articles or as parts of larger works. -

Hana Taragan HISTORICAL REFERENCE in MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE: BAYBARS's BUILDINGS in PALESTINE

the israeli academic center in cairo ¯È‰˜· Èχ¯˘È‰ ÈÓ„˜‡‰ ÊίӉ Hana Taragan HISTORICAL REFERENCE IN MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE: BAYBARS’S BUILDINGS IN PALESTINE Hana Taragan is a lecturer in Islamic art at Tel Aviv University, where she received her Ph.D. in 1992. Her current research concerns Umayyad and Mamluk architecture in Eretz Israel in the medieval period. She is the author of Art and Patronage in the Umayyad Palace in Jericho (in Hebrew) and of numerous articles in the field of Islamic art. In the year 1274, al-Malik al-Zahir also changed a structure’s function Baybars, the first Mamluk ruler of from church to mosque, as he did Palestine (1260–1277), ordered the in Qaqun.5 addition of a riwaq (porch) to the Baybars’s choice of Yavne may tomb of Abu Hurayra in Yavne.1 be explained by the ruin of the The riwaq, featuring a tripartite coastal towns, or by Yavne’s loca- portal and six tiny domes, had two tion on the main road from Cairo arches decorated with cushion to Damascus. However, it seems to voussoirs and one with a zigzag me that above and beyond any frieze (Figure 1). Baybars also strategic and administrative con- installed a dedicatory inscription siderations, Baybars focused on naming himself as builder of the this site in an attempt to exploit riwaq.2 The addition of a portal to Abu Hurayra’s tomb as a means of the existing tomb structure typifies institutionalizing the power of the Baybars’s building policy in Pales- Mamluk dynasty in general and tine. -

TOMBS and FOOTPRINTS: ISLAMIC SHRINES and PILGRIMAGES IN^IRAN and AFGHANISTAN Wvo't)&^F4

TOMBS AND FOOTPRINTS: ISLAMIC SHRINES AND PILGRIMAGES IN^IRAN AND AFGHANISTAN WvO'T)&^f4 Hugh Beattie Thesis presented for the degree of M. Phil at the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies 1983 ProQuest Number: 10672952 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672952 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 abstract:- The thesis examines the characteristic features of Islamic shrines and pilgrimages in Iran and Afghan istan, in doing so illustrating one aspect of the immense diversity of belief and practice to be found in the Islamic world. The origins of the shrine cults are outlined, the similarities between traditional Muslim and Christian attitudes to shrines are emphasized and the functions of the shrine and the mosque are contrasted. Iranian and Afghan shrines are classified, firstly in terms of the objects which form their principal attrac tions and the saints associated with them, and secondly in terms of the distances over which they attract pilgrims. The administration and endowments of shrines are described and the relationship between shrines and secular authorities analysed.