Migration, Marginalization, and Community Development: 1900-1939

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SENIOR AWARDS LUNCHEON Mission: to Enrich Lives Through Healthy Eating

8th Annual SENIOR AWARDS LUNCHEON Mission: To enrich lives through healthy eating. FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2019 Silent Auction - 10:30 a.m. Luncheon and Program - 11:30 a.m. Arizona Biltmore | Phoenix, AZ A warm welcome to all—ourWelcome sponsors, supporters, guests, and volunteers! On behalf of the Board of Directors, thank you for joining us at the Gregory’s Fresh Market 8th Annual Senior Awards Luncheon. You do make a dierence! Your generosity has enabled Gregory’s Fresh Market to support the health and well-being of seniors for the last nine years. Nearly 8,000 seniors residing in sixty independent living facilities in the Greater Phoenix area have been served by GFM. Today we gratefully honor the accomplishments of seniors and their residential service coordinators and celebrate GFM’s progress towards All proceeds from the luncheon fulfilling its mission to enrich lives. Diana Gregory’s Outreach Services will directly benefit senior (DGOS) is dedicated to the health, nutrition and fitness of all Arizona nutrition and health. Overall, seniors. GFM directly addresses the health disparities confronting 99% of the funds GFM raises under-resourced communities. We do so primarily through our are spent solely on the selection mobile produce market, which operates in senior communities lacking and delivery of fresh fruits and easy access to healthy food. And our holistic approach also includes vegetables. By visiting us online, community organizing, advocacy and education to increase senior learn more about our programs awareness and adoption of healthy food choices. at www.dianagregory.com, on Facebook at Gregory’s Fresh Please join in congratulating this year’s honorees and their commitment Market Place and on Twitter to our communities. -

Fitzgerald in the Late 1910S: War and Women Richard M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duquesne University: Digital Commons Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2009 Fitzgerald in the Late 1910s: War and Women Richard M. Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Clark, R. (2009). Fitzgerald in the Late 1910s: War and Women (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/416 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Richard M. Clark August 2009 Copyright by Richard M. Clark 2009 FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN By Richard M. Clark Approved July 21, 2009 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda Kinnahan, Ph.D. Greg Barnhisel, Ph.D. Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Dissertation Director) (2nd Reader) ________________________________ ________________________________ Frederick Newberry, Ph.D. Magali Cornier Michael, Ph.D. Professor of English Professor of English (1st Reader) (Chair, Department of English) ________________________________ Christopher M. Duncan, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN By Richard M. Clark August 2009 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda Kinnahan This dissertation analyzes historical and cultural factors that influenced F. -

A Life Transformed: the 1910S

TWO A Life Transformed: The 1910s Not the least significant element of modem political history is contained in the constant growth of individual personality accompanied by the limitation of the State.! Georg Jellinek, 1892 FIRST TRIP TO CHINA AND THE JAPANESE COMMUNITY IN PEKING When Nakae grew bored with working for the South Manchurian Rail way Company, once again his benefactors came to his rescue and found something else for him. Around October 1914, his mother's former boarder, Ts'ao Ju-lin, managed to land him an offer. Ts'ao summoned Nakae to Peking with a one-year contract to work as secretary to Ariga Nagao (1860-1921). Ariga was a professor of international law at Waseda University and had been a friend of Ushikichi's father, although thei; political views diverged sharply. Apparently, years before, Mrs. Nakae out of concern for her wayward son's future had prevailed on the ever grateful Ts'ao to intercede on behalf of Ushikichi if necessary. Nakae received the handsome monthly salary of one hundred yuan for responsibilities neither especially demanding nor explicit. One suspects that he held this sinecure, which might otherwise not have existed, because of his mother's earlier appeal. We know, however, that Nakae spent a great deal of his time in China that year leading what he himself would later refer to as the life of a "profligate villain" (hi5ti5 burai).2 In 1914 Ariga accepted an invitation to serve as an advisor to the gov- "'-------------------- -- 28 A Life Transformed ernment of Yuan Shih-k'ai (1859-1916), which had taken power several years earlier in the young Republic of China. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

South Central Neighborhoods Transit Health Impact Assessment

SOUTH CENTRAL NEIGHBORHOODS TRANSIT HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT WeArePublicHealth.org This project is supported by a grant from the Health Impact Project, a collaboration of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and The Pew Charitable Trusts, through the Arizona Department of Health Services. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Health Impact Project, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation or The Pew Charitable Trusts. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS South Central Neighborhoods Transit Health Impact Assessment (SCNTHIA) began in August 2013 and the Final Report was issued January 2015. Many individuals and organizations provided energy and expertise. First, the authors wish to thank the numerous residents and neighbors within the SCNTHIA study area who participated in surveys, focus groups, key informant interviews and walking assessments. Their participation was critical for the project’s success. Funding was provided by a generous grant from the Health Impact Project through the Arizona Department of Health Services. Bethany Rogerson and Jerry Spegman of the Health Impact Project, a collaboration between the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and The Pew Charitable Trusts, provided expertise, technical assistance, perspective and critical observations throughout the process. The SCNTHIA project team appreciates the opportunities afforded by the Health Impact Project and its team members. The Arizona Alliance for Livable Communities works to advance health considerations in decision- making. The authors thank the members of the AALC for their commitment and dedication to providing technical assistance and review throughout this project. The Insight Committee (Community Advisory Group) deserves special recognition. They are: Community Residents Rosie Lopez George Young; South Mountain Village Planning Committee Community Based Organizations Margot Cordova; Friendly House Lupe Dominguez; St. -

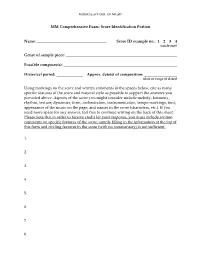

MM Comprehensive Exam: Score Identification Portion Name

MOORES SCHOOL OF MUSIC MM Comprehensive Exam: Score Identification Portion Name: Score ID example no.: 1 2 3 4 (circle one) Genre of sample piece: Possible composer(s): Historical period: Approx. date(s) of composition: (date or range of dates) Using markings on the score and written comments in the spaces below, cite as many specific features of the score and musical style as possible to support the answers you provided above. Aspects of the score you might consider include melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, dynamics, form, orchestration, instrumentation, tempo markings, font, appearance of the music on the page, and names in the score (characters, etc.). If you need more space for any answer, feel free to continue writing on the back of this sheet. Please note that in order to receive credit for your response, you must include written comments on specific features of the score; simply filling in the information at the top of this form and circling features in the score (with no commentary) is not sufficient. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Andrew Davis. rev. Nov 2009. General information on preparing for a comprehensive exam in music (geared especially toward answering questions in music theory and/or discussing unidentified scores): Comprehensive exams (especially music theory portions, and to some extent score identification portions, if applicable) ask you to focus on broad theoretical and/or stylistic topics that you're expected to know as a literate musician with a graduate degree in music. For example, in the course of the exam you might -

Phoenix Suns Charities Awards More Than $1

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: November 18, 2015 Contact: Casey Taggatz, [email protected], 602-379-7912 Kelsey Dickerson, [email protected], 602-379-7535 PHOENIX SUNS CHARITIES AWARDS MORE THAN $1 MILLION IN GRANTS TO VALLEY NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATIONS Girl Scouts - Arizona Cactus-Pine Council awarded $100,000 Playmaker Award grant; More than 115 charitable organizations received grants PHOENIX – Phoenix Suns Charities announced its 2015-16 grant recipients during a special reception, brought to you by Watertree Health ®, at Talking Stick Resort Arena last night. This year, the charity granted more than $1 million to 119 non-profit organizations throughout Arizona. “The Phoenix Suns organization is thrilled to have the opportunity to support the incredible work of our grant recipients,” said Sarah Krahenbuhl, Executive Director of Phoenix Suns Charities. “In addition to our support for Central High School, the Board chose to award three impact grants to the Girl Scouts, Boys & Girls Clubs of Metro Phoenix and to Jewish Family & Children’s Service. The mission of Phoenix Suns Charities is to support children and family services throughout Arizona and we are proud to be a part of organizations that make our community better every day.” The $100,000 Playmaker grant to Girl Scouts – Arizona Cactus-Pine Council will support The Leadership Center for Girls and Women at Camp Sombrero in South Phoenix. In addition, Boys & Girls Clubs of Metro Phoenix will use the $50,000 grant in the construction of a new gymnasium. And, Jewish Family & Children’s Service will use its $50,000 grant to provide integrated medical and behavioral health services to the Maryvale neighborhood of Phoenix. -

Bisbee, Arizona Field Trip

Mesa Community College urban bicycle tour March 5 & 6, 2011 Trip Leaders: Steve Bass and Philip Clinton FIELD TRIP OBJECTIVES 1. to observe the distribution of human activities and land uses 2. to observe the distribution of biotic, geologic, and atmospheric phenomena 3. to interact with the human and natural environment 4. to gain an appreciation of the diversity of the Phoenix Metropolitan area 5. to build a community of learners in a relaxed setting FIELD TRIP RULES 1. All participants must wear an approved helmet while cycling and a seat belt when traveling by motor vehicle. 2. Use of audio headsets is prohibited while cycling. 3. Participants will travel as a group and stop for discussions along the way. 4. Obey all traffic rules and ride defensively. This is not a race. 5. Pack it in – pack it out. Leave no trash along the route. Itinerary (all times are approximate) Saturday March 5 8 am Depart MCC (arrive by 7:30 am to load gear and to enjoy breakfast) 10 am Snack Break near Camelback Colonnade Mall 12 pm Picnic lunch at Cortez Park 2 pm Arrive at GCC 3 pm Arrive at White Tank Mountain Regional Park 6 pm Dinner Cookout followed by sitting around the campfire & smores Sunday March 6 7 am Breakfast (and stretching) 8 am Depart White Tank Mountain Regional Park by van 9 am Depart GCC by bicycle 10 am Tour the Bharatiya Ekta Mandir Hindu and Jain Temple 12 pm Snack at Encanto Park 1 pm Lunch at South Mountain Community College 3 pm Arrive at MCC 1 SATURDAY ROUTE Begin at the Dobson & Southern campus of Mesa Community College. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Aspects of Jazz and Classical Music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2002 Aspects of jazz and classical music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini Heather Koren Pinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pinson, Heather Koren, "Aspects of jazz and classical music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini" (2002). LSU Master's Theses. 2589. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2589 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASPECTS OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL MUSIC IN DAVID N. BAKER’S ETHNIC VARIATIONS ON A THEME OF PAGANINI A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in The School of Music by Heather Koren Pinson B.A., Samford University, 1998 August 2002 Table of Contents ABSTRACT . .. iii INTRODUCTION . 1 CHAPTER 1. THE CONFLUENCE OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL MUSIC 2 CHAPTER 2. ASPECTS OF MODELING . 15 CHAPTER 3. JAZZ INFLUENCES . 25 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 48 APPENDIX 1. CHORD SYMBOLS USED IN JAZZ ANALYSIS . 53 APPENDIX 2 . PERMISSION TO USE COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL . 54 VITA . 55 ii Abstract David Baker’s Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini (1976) for violin and piano bring together stylistic elements of jazz and classical music, a synthesis for which Gunther Schuller in 1957 coined the term “third stream.” In regard to classical aspects, Baker’s work is modeled on Nicolò Paganini’s Twenty-fourth Caprice for Solo Violin, itself a theme and variations. -

Phoenix, AZ 85003 Telephone: (602) 256-3452 Email: [email protected]

===+ Community Action Plan for South Phoenix, Arizona LOCAL FOODS, LOCAL PLACES TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE November 2018 For more information about Local Foods, Local Places visit: https://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/local-foods-local-places CONTACT INFORMATION: Phoenix, Arizona Contact: Rosanne Albright Environmental Programs Coordinator City Manager’s Office, Office of Environmental Programs 200 W. Washington, 14th Floor Phoenix, AZ 85003 Telephone: (602) 256-3452 Email: [email protected] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Project Contact: John Foster Office of Community Revitalization U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 1200 Pennsylvania Ave. NW (MC 1807T) Washington, DC 20460 Telephone: (202) 566-2870 Email: [email protected] All photos in this document are courtesy of U.S. EPA or its consultants unless otherwise noted. Front cover photo credit (top photo): Rosanne Albright LOCAL FOODS, LOCAL PLACES COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN South Phoenix, Arizona COMMUNITY STORY South Phoenix, Arizona, along with Maricopa County and the greater Phoenix metropolitan area, lies within the Salt River Watershed.1 Despite the shared geohistorical connections to the Salt River, the history and development of South Phoenix is vastly different from the rest of Phoenix. The history of the South Phoenix corridor along the Salt River, generally south of the railroad tracks, is a story of many different people carving out an existence for themselves and their families and persisting despite many extreme challenges. Its historical challenges include extreme poverty in an area that offered primarily low-wage agricultural and some industrial jobs; regional indifference and often hostile racist attitudes that restricted economic opportunities; unregulated land use and relatively late city annexation of a predominantly minority district; lack of investments in housing stock and Figure 1 – Colorful wall mural separating the Spaces of basic infrastructure; and industrialization that engendered Opportunity Farm Park from residential homes. -

History and Social Science Standards Are Premised Upon a Rigorous and Relevant K-12 Social Studies Program Within Each District and School in the State

History andArizona Social Science Standards DRAFT: March, 2018 Introduction Since the founding of this Nation, education and democracy have gone hand in hand...[Thomas] Jefferson and the Founders believed a nation that governs itself, like ours, must rely upon an informed and engaged electorate. Their purpose was not only to teach all Americans how to read and write but to instill the self-evident truths that are the anchors of our political system. Ronald Reagan An important aspect of our Republic is that an educated and engaged citizenry is vital for the system to work. In a government where the final authority and sovereignty rests with the people, our local, state, and federal governments will only be as responsive as the citizens demand them to be. Preparing students for the 21st century cannot be accomplished without a strong emphasis on civics, economics, geography, and history – the core disciplines of the social studies. It is imperative that each generation gains an understanding of the knowledge, skills, and dispositions to participate fully in civic life in a rapidly changing world. The Arizona History and Social Science Standards are premised upon a rigorous and relevant K-12 social studies program within each district and school in the state. Engaging students in the pursuit of active, informed citizenship will require a broad range of understandings and skills including: Think analytically by • Posing and framing questions • Gathering a variety of evidence • Recognizing continuity and detecting change over time • Utilizing