South Central Neighborhoods Transit Health Impact Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SENIOR AWARDS LUNCHEON Mission: to Enrich Lives Through Healthy Eating

8th Annual SENIOR AWARDS LUNCHEON Mission: To enrich lives through healthy eating. FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2019 Silent Auction - 10:30 a.m. Luncheon and Program - 11:30 a.m. Arizona Biltmore | Phoenix, AZ A warm welcome to all—ourWelcome sponsors, supporters, guests, and volunteers! On behalf of the Board of Directors, thank you for joining us at the Gregory’s Fresh Market 8th Annual Senior Awards Luncheon. You do make a dierence! Your generosity has enabled Gregory’s Fresh Market to support the health and well-being of seniors for the last nine years. Nearly 8,000 seniors residing in sixty independent living facilities in the Greater Phoenix area have been served by GFM. Today we gratefully honor the accomplishments of seniors and their residential service coordinators and celebrate GFM’s progress towards All proceeds from the luncheon fulfilling its mission to enrich lives. Diana Gregory’s Outreach Services will directly benefit senior (DGOS) is dedicated to the health, nutrition and fitness of all Arizona nutrition and health. Overall, seniors. GFM directly addresses the health disparities confronting 99% of the funds GFM raises under-resourced communities. We do so primarily through our are spent solely on the selection mobile produce market, which operates in senior communities lacking and delivery of fresh fruits and easy access to healthy food. And our holistic approach also includes vegetables. By visiting us online, community organizing, advocacy and education to increase senior learn more about our programs awareness and adoption of healthy food choices. at www.dianagregory.com, on Facebook at Gregory’s Fresh Please join in congratulating this year’s honorees and their commitment Market Place and on Twitter to our communities. -

Urban Waters Partnership RIO REIMAGINED WATERSHED WORK PLAN 2019 - 2020

Urban Waters Partnership RIO REIMAGINED WATERSHED WORK PLAN 2019 - 2020 PILOT LOCATION: Salt River and Middle Gila River Watershed POINTS OF CONTACT: Melissa McCann, ASU University City Exchange – Project Director Jared Vollmer, UWFP - U.S. EPA BACKGROUND: Includes the 58 miles along both the Salt and Gila Rivers, with its headwaters from three larger watersheds: the Salt which starts west of Alpine, AZ; the Upper Gila which starts east of Baldy Mountain in New Mexico; and the San Pedro which starts in Mexico. All three watersheds eventually converge east of Phoenix and drain into the Middle Gila (Phoenix Metro area) and then to the Lower Gila River and finally the Colorado River which takes the remaining water away in a series of diversions at the US and Mexico border. SRP Water Infrastructure Facts § 8.3 million acre watershed § 8 dams – storing water in wet years to ensure reliable supplies in dry years, and generating clean renewable power § 131 miles of canals and 1,000 miles of laterals and ditches to move water to cities and agricultural water users § Salt River Watershed is 15,000 square miles FEDERAL Agencies Participating AGENCY FEDERAL / REGIONAL STATE / LOCAL DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE | USDA U.S. Forest Service Laura Moser - Cooperative Forestry, Asst. Program John Richardson - Program Manager, UCF | Mgr. for SW Region FH, AZ Dept. of Forestry + FM Micah Grondin – Program Manager, AZ Dept. of Forestry + FM Natural Resource Conservation Service | NRCS Terry D'Addio – National RC&D Program Mgr. Keisha Tatem – State Conservationist -

EST NAME CNTY NAME Type PRIM PHONE P ADDR1 P CITY

EST_NAME CNTY_NAME Type PRIM_PHONE P_ADDR1 P_CITY P_STATE P_ZIP5 LicNo BAXLEY ANIMAL CONTROL, CITY OF APPLING 33 912-367-8300 282 E Parker St Baxley GA 31513 332584 CITY OF PEARSON, THE ATKINSON 33 912-422-3397 89 MAIN ST S PEARSON GA 31642 3399687 THE CITY OF WILLACOOCHEE ATKINSON 33 912-534-5991 33 Fleetwood Ave W Willacoochee GA 31650 33104158 CITY OF ALMA ANIMAL SHELTER BACON 33 912-632-8751 884 RADIO STATION RD (LANDFILL) ALMA GA 31510 333750 ANIMAL RESCUE FOUNDATION BALDWIN 33 478-454-1273 711 S WILKINSON ST MILLEDGEVILLE GA 31059 3355497 BALDWIN COUNTY ANIMAL CONTROL BALDWIN 33 478-445-4791 1365 ORCHARD HILL RD MILLEDGEVILLE GA 31061 3321946 OLD CAPITAL PET CARE BALDWIN 33 478-452-9760 691 DUNLAP RD NE MILLEDGEVILLE GA 31061 3356744 BANKS COUNTY BANKS 33 706-677-6200 144 YONAH HOMER RD HOMER GA 30547 3389527 Pet Coalition of Georgia BANKS 33 678-410-4422 1147 Sims Bridge Rd Commerce GA 30530 33104765 BARROW COUNTY ANIMAL CONTROL BARROW 33 770-307-3012 610 BARROW PARK DR WINDER GA 30680 3341750 LEFTOVER PETS INC. BARROW 33 706-654-3291 610 Barrow Park Dr Winder GA 30680 3394405 PUP & CAT CO BARROW 33 770-867-1622 118 W CANDLER ST WINDER GA 30680 3366580 REMEMBER ME? PET RESCUE, LLC BARROW 33 770-295-9491 1022 CYPERTS TRAIL WINDER GA 30680 33105132 BARTOW COUNTY ANIMAL SHELTER BARTOW 33 770-387-5153 50 LADDS MOUNTAIN RD SW CARTERSVILLE GA 30120 3320763 CARTERSVILLE ANIMAL CONTROL BARTOW 33 770-382-2526 195 CASSVILLE RD CARTERSVILLE GA 30120 3384548 ETOWAH VALLEY HUMANE SOCIETY BARTOW 33 770-383-3338 36 LADDS MOUNTAIN RD SW CARTERSVILLE GA 30120 3373047 HUMANE LEAGUE OF LAKE LANIER BARTOW 33 404-358-4498 37 Oak Hill Ln NW Cartersville GA 30121 3394553 BEN HILL COUNTY BEN HILL 33 229-426-5100 402 E PINE ST FITZGERALD GA 31750 3380118 CITY OF FITZGERALD ANIMAL CONTROL BEN HILL 33 229-426-5000 302 E Central Ave Fitzgerald GA 31750 3380122 FITZGERALD BEN HILL HUMANE SOCIETY BEN HILL 33 229-426-5078 106 LIONS PARK RD FITZGERALD GA 31750 334018 BERRIEN CO HUMANE SOCIETY, INC. -

Firearms Ownership and Regulation: Tackling an Old Problem with Renewed Vigor

William & Mary Law Review Volume 20 (1978-1979) Issue 2 Article 3 December 1978 Firearms Ownership and Regulation: Tackling an Old Problem with Renewed Vigor David T. Hardy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Repository Citation David T. Hardy, Firearms Ownership and Regulation: Tackling an Old Problem with Renewed Vigor, 20 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 235 (1978), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol20/iss2/3 Copyright c 1978 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr FIREARM OWNERSHIP AND REGULATION: TACKLING AN OLD PROBLEM WITH RENEWED VIGOR DAVID T. HARDY* During the decade 1964-1974, approximately six books,' forty-two legal articles,2 and five Congressional hearings' were devoted solely to airing arguments on the desirability of firearms regulations. De- spite what these numbers might suggest about the exhaustiveness of gun control studies, a close examination of the bulk of the pre- 1975 publications disclosed a great shortage of empirical data and comprehensive analysis. With several exceptions, assertions and * B.A., J.D., University of Arizona; Partner, Law Offices of Sando & Hardy, Tucson, Arizona. The author currently is serving as a general consultant to the Director of the Na- tional Rifle Association, Washington, D.C. 1. See C. BAKAL, THE RIGHT TO BEAR ARMS (1966); B. DAVIDSON, To KEEP AND BEAR ARMS (1969); C. GREENWOOD, FIREARMS CONTROL (1972); R. KUKILA, GUN CONTROL (1973); G. NEWTON & F. ZIMRING, FIREARMS AND VIOLENCE IN AMERICAN LIFE (1969); R. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE October 1, 2001

October 1, 2001 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE 18161 of S. 1467, a bill to amend the Hmong will award a gold medal on behalf of have distinguished records of public service Veterans’ Naturalization Act of 2000 to the Congress to Reverend Doctor Mar- to the American people and the inter- extend the deadlines for application tin Luther King, Jr., posthumously, national community; and payment of fees. (2) Dr. King preached a doctrine of non- and his widow Coretta Scott King in violent civil disobedience to combat segrega- S.J. RES. 12 recognition of their contributions to tion, discrimination, and racial injustice; At the request of Mr. SMITH of New the Nation on behalf of the civil rights (3) Dr. King led the Montgomery bus boy- Hampshire, the name of the Senator movement. It is time to honor Dr. Mar- cott for 381 days to protest the arrest of Mrs. from New Hampshire (Mr. GREGG) was tin Luther King, Jr. and his widow Rosa Parks and the segregation of the bus added as a cosponsor of S.J. Res. 12, a Coretta Scott King, the first family of system of Montgomery, Alabama; joint resolution granting the consent the civil rights movement, for their (4) in 1963, Dr. King led the march on Wash- of Congress to the International Emer- distinguished records of public service ington, D.C., that was followed by his famous address, the ‘‘I Have a Dream’’ speech; gency Management Assistance Memo- to the American people and the inter- (5) through his work and reliance on non- randum of Understanding. -

Department of Port Control Divisions of Cleveland Hopkins International and Burke Lakefront Airports

CITY OF CLEVELAND, OHIO DEPARTMENT OF PORT CONTROL DIVISIONS OF CLEVELAND HOPKINS INTERNATIONAL AND BURKE LAKEFRONT AIRPORTS REPORT ON AUDITS OF FINANCIAL STATEMENTS For the years ended December 31, 2014 and 2013 CITY OF CLEVELAND, OHIO DEPARTMENT OF PORT CONTROL DIVISIONS OF CLEVELAND HOPKINS INTERNATIONAL AND BURKE LAKEFRONT AIRPORTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Independent Auditors’ Report .................................................................................................... 1-2 Management’s Discussion and Analysis ................................................................................... 3-16 Statements of Net Position ......................................................................................................... 18-19 Statements of Revenues, Expenses and Changes in Net Position ............................................. 21 Statements of Cash Flows .......................................................................................................... 22-23 Notes to Financial Statements .................................................................................................... 25-42 Schedule of Airport Revenues and Operating Expenses as Defined in the Airline Use Agreements ................................................................................ 43 Report on Compliance for the Passenger Facility Charge Program; Report on Internal Control Over Compliance; and Report on Schedule of Expenditures of Passenger Facility Charges In Accordance with 14 CFR Part 158 ...................................... -

Phoenix Suns Charities Awards More Than $1

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: November 18, 2015 Contact: Casey Taggatz, [email protected], 602-379-7912 Kelsey Dickerson, [email protected], 602-379-7535 PHOENIX SUNS CHARITIES AWARDS MORE THAN $1 MILLION IN GRANTS TO VALLEY NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATIONS Girl Scouts - Arizona Cactus-Pine Council awarded $100,000 Playmaker Award grant; More than 115 charitable organizations received grants PHOENIX – Phoenix Suns Charities announced its 2015-16 grant recipients during a special reception, brought to you by Watertree Health ®, at Talking Stick Resort Arena last night. This year, the charity granted more than $1 million to 119 non-profit organizations throughout Arizona. “The Phoenix Suns organization is thrilled to have the opportunity to support the incredible work of our grant recipients,” said Sarah Krahenbuhl, Executive Director of Phoenix Suns Charities. “In addition to our support for Central High School, the Board chose to award three impact grants to the Girl Scouts, Boys & Girls Clubs of Metro Phoenix and to Jewish Family & Children’s Service. The mission of Phoenix Suns Charities is to support children and family services throughout Arizona and we are proud to be a part of organizations that make our community better every day.” The $100,000 Playmaker grant to Girl Scouts – Arizona Cactus-Pine Council will support The Leadership Center for Girls and Women at Camp Sombrero in South Phoenix. In addition, Boys & Girls Clubs of Metro Phoenix will use the $50,000 grant in the construction of a new gymnasium. And, Jewish Family & Children’s Service will use its $50,000 grant to provide integrated medical and behavioral health services to the Maryvale neighborhood of Phoenix. -

2110 W Southern

2110 W Southern Ave West of Northwest Corner Southern Avenue & Dobson Road | Mesa, Arizona S S McKellips 202 University Country Club Country Club Main S. SanJose Stapley Optometry Stapley 60 Baseline Rural Rural Mesa Guadalupe Mesa 101 McClintock McClintock Dobson 1,250 SF Elliot Dobson Kyrene Available Kyrene 750 SF Warner Available Arizona Arizona Alma School Alma School Ray Priest Priest Wild Thyme Wild Property Highlights Demographics Contact • Two spaves available: 750 SF & 1,250 SF JASON FESSINGER ........602.368.1090 Can be combined 1 miles 3 miles 5 miles [email protected] Estimated Population 24,251 171,095 405,341 • Located across from Banner Desert Medical Center KALEN RICKARD ...........602.931.4492 & Mesa Community College Average HH Income $48,899 $60,048 $64,754 [email protected] • Located within close proximity to Workplace Employees 11,796 81,860 204,800 Loop 101 & US-60 Freeways Daytime Population 19,443 131,569 324,880 • 34,900 VPD along Southern Ave WESTERN RETAIL ADVISORS The information contained within this brochure has been obtained from sources other than Western Retail Advisors, LLC. Western Retail Advisors has not verified such information and makes no guarantee warranty or representation about such 2555 E Camelback Rd, Ste 200, Phoenix, AZ 85016 information. It is your responsibility to independently confirm its accuracy and completeness. Any dimensions, specifications, floor plans and information may not be accurate and should be verified by you prior to the lease or purchase of the property. 2110 W Southern -

Bisbee, Arizona Field Trip

Mesa Community College urban bicycle tour March 5 & 6, 2011 Trip Leaders: Steve Bass and Philip Clinton FIELD TRIP OBJECTIVES 1. to observe the distribution of human activities and land uses 2. to observe the distribution of biotic, geologic, and atmospheric phenomena 3. to interact with the human and natural environment 4. to gain an appreciation of the diversity of the Phoenix Metropolitan area 5. to build a community of learners in a relaxed setting FIELD TRIP RULES 1. All participants must wear an approved helmet while cycling and a seat belt when traveling by motor vehicle. 2. Use of audio headsets is prohibited while cycling. 3. Participants will travel as a group and stop for discussions along the way. 4. Obey all traffic rules and ride defensively. This is not a race. 5. Pack it in – pack it out. Leave no trash along the route. Itinerary (all times are approximate) Saturday March 5 8 am Depart MCC (arrive by 7:30 am to load gear and to enjoy breakfast) 10 am Snack Break near Camelback Colonnade Mall 12 pm Picnic lunch at Cortez Park 2 pm Arrive at GCC 3 pm Arrive at White Tank Mountain Regional Park 6 pm Dinner Cookout followed by sitting around the campfire & smores Sunday March 6 7 am Breakfast (and stretching) 8 am Depart White Tank Mountain Regional Park by van 9 am Depart GCC by bicycle 10 am Tour the Bharatiya Ekta Mandir Hindu and Jain Temple 12 pm Snack at Encanto Park 1 pm Lunch at South Mountain Community College 3 pm Arrive at MCC 1 SATURDAY ROUTE Begin at the Dobson & Southern campus of Mesa Community College. -

Phoenix, AZ 85003 Telephone: (602) 256-3452 Email: [email protected]

===+ Community Action Plan for South Phoenix, Arizona LOCAL FOODS, LOCAL PLACES TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE November 2018 For more information about Local Foods, Local Places visit: https://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/local-foods-local-places CONTACT INFORMATION: Phoenix, Arizona Contact: Rosanne Albright Environmental Programs Coordinator City Manager’s Office, Office of Environmental Programs 200 W. Washington, 14th Floor Phoenix, AZ 85003 Telephone: (602) 256-3452 Email: [email protected] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Project Contact: John Foster Office of Community Revitalization U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 1200 Pennsylvania Ave. NW (MC 1807T) Washington, DC 20460 Telephone: (202) 566-2870 Email: [email protected] All photos in this document are courtesy of U.S. EPA or its consultants unless otherwise noted. Front cover photo credit (top photo): Rosanne Albright LOCAL FOODS, LOCAL PLACES COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN South Phoenix, Arizona COMMUNITY STORY South Phoenix, Arizona, along with Maricopa County and the greater Phoenix metropolitan area, lies within the Salt River Watershed.1 Despite the shared geohistorical connections to the Salt River, the history and development of South Phoenix is vastly different from the rest of Phoenix. The history of the South Phoenix corridor along the Salt River, generally south of the railroad tracks, is a story of many different people carving out an existence for themselves and their families and persisting despite many extreme challenges. Its historical challenges include extreme poverty in an area that offered primarily low-wage agricultural and some industrial jobs; regional indifference and often hostile racist attitudes that restricted economic opportunities; unregulated land use and relatively late city annexation of a predominantly minority district; lack of investments in housing stock and Figure 1 – Colorful wall mural separating the Spaces of basic infrastructure; and industrialization that engendered Opportunity Farm Park from residential homes. -

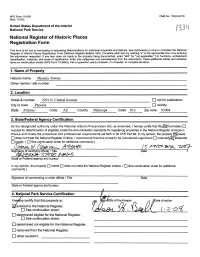

Phoenix Towers______Other Names / Site Number

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior B3' National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_______________________________________________ Historic name Phoenix Towers_______________________________________________ Other names / site number 2. Location Street & number 2201 N. Central Avenue __ [U not for publication City or town Phoenix __ D vicinity State Arizona Code AZ County Maricopa Code 013 Zip code 85004 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this^H^nomination d request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property Sjneets d does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant d nationally^B^atewide d locally. -

Central Ave Corridor Summary

CCENTRALENTRAL AAVENUEVENUE CCORRIDORORRIDOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY CITY OF PHOENIX PHOENIX C OMMUNITY ALLIANCE V ALLEY SUMMARY REPORT METRO R AIL Introduction Situated in the center of the Greater Phoenix region, the Central Avenue Corridor is a major employment center that features the highest concentration of office space in the metropolitan area. In 2004, construction of a regional light rail transit (LRT) system that will serve the Corridor is scheduled to begin. The planned LRT system creates an opportunity to alter and strategically plan new commercial and residential development in the corridor,while creating a unique and vibrant live,work and play environment. On September 19, 2002, the City of Phoenix, the Phoenix Community Alliance and Valley Metro Rail held a day-long Central Avenue Corridor workshop for community leaders and real estate professionals to: • Examine development patterns and recent trends in the Corridor; • Understand the current, intermediate and long-term market challenges within the Corridor; and • Consider how light rail transit will affect future development in the Central Avenue Corridor. The workshop participants included property owners, private and institutional investors, developers, brokers, community leaders and design firms. For purposes of the workshop, the Central Avenue Corridor was defined as the area generally bounded by Camelback Road to the North, Van Buren Street to the South, 3rd Street to the East and 3rd Avenue to the West (the "Corridor"). As a follow-up to the workshop, the City and the Phoenix Community Alliance along with EDAW conducted a design exercise in the spring of 2003 to further develop, define and illustrate the mixed-use/transit oriented development concepts that were discussed at the workshop.