Community Action Plan for South Phoenix, Arizona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SENIOR AWARDS LUNCHEON Mission: to Enrich Lives Through Healthy Eating

8th Annual SENIOR AWARDS LUNCHEON Mission: To enrich lives through healthy eating. FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2019 Silent Auction - 10:30 a.m. Luncheon and Program - 11:30 a.m. Arizona Biltmore | Phoenix, AZ A warm welcome to all—ourWelcome sponsors, supporters, guests, and volunteers! On behalf of the Board of Directors, thank you for joining us at the Gregory’s Fresh Market 8th Annual Senior Awards Luncheon. You do make a dierence! Your generosity has enabled Gregory’s Fresh Market to support the health and well-being of seniors for the last nine years. Nearly 8,000 seniors residing in sixty independent living facilities in the Greater Phoenix area have been served by GFM. Today we gratefully honor the accomplishments of seniors and their residential service coordinators and celebrate GFM’s progress towards All proceeds from the luncheon fulfilling its mission to enrich lives. Diana Gregory’s Outreach Services will directly benefit senior (DGOS) is dedicated to the health, nutrition and fitness of all Arizona nutrition and health. Overall, seniors. GFM directly addresses the health disparities confronting 99% of the funds GFM raises under-resourced communities. We do so primarily through our are spent solely on the selection mobile produce market, which operates in senior communities lacking and delivery of fresh fruits and easy access to healthy food. And our holistic approach also includes vegetables. By visiting us online, community organizing, advocacy and education to increase senior learn more about our programs awareness and adoption of healthy food choices. at www.dianagregory.com, on Facebook at Gregory’s Fresh Please join in congratulating this year’s honorees and their commitment Market Place and on Twitter to our communities. -

South Central Neighborhoods Transit Health Impact Assessment

SOUTH CENTRAL NEIGHBORHOODS TRANSIT HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT WeArePublicHealth.org This project is supported by a grant from the Health Impact Project, a collaboration of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and The Pew Charitable Trusts, through the Arizona Department of Health Services. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Health Impact Project, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation or The Pew Charitable Trusts. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS South Central Neighborhoods Transit Health Impact Assessment (SCNTHIA) began in August 2013 and the Final Report was issued January 2015. Many individuals and organizations provided energy and expertise. First, the authors wish to thank the numerous residents and neighbors within the SCNTHIA study area who participated in surveys, focus groups, key informant interviews and walking assessments. Their participation was critical for the project’s success. Funding was provided by a generous grant from the Health Impact Project through the Arizona Department of Health Services. Bethany Rogerson and Jerry Spegman of the Health Impact Project, a collaboration between the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and The Pew Charitable Trusts, provided expertise, technical assistance, perspective and critical observations throughout the process. The SCNTHIA project team appreciates the opportunities afforded by the Health Impact Project and its team members. The Arizona Alliance for Livable Communities works to advance health considerations in decision- making. The authors thank the members of the AALC for their commitment and dedication to providing technical assistance and review throughout this project. The Insight Committee (Community Advisory Group) deserves special recognition. They are: Community Residents Rosie Lopez George Young; South Mountain Village Planning Committee Community Based Organizations Margot Cordova; Friendly House Lupe Dominguez; St. -

Phoenix Suns Charities Awards More Than $1

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: November 18, 2015 Contact: Casey Taggatz, [email protected], 602-379-7912 Kelsey Dickerson, [email protected], 602-379-7535 PHOENIX SUNS CHARITIES AWARDS MORE THAN $1 MILLION IN GRANTS TO VALLEY NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATIONS Girl Scouts - Arizona Cactus-Pine Council awarded $100,000 Playmaker Award grant; More than 115 charitable organizations received grants PHOENIX – Phoenix Suns Charities announced its 2015-16 grant recipients during a special reception, brought to you by Watertree Health ®, at Talking Stick Resort Arena last night. This year, the charity granted more than $1 million to 119 non-profit organizations throughout Arizona. “The Phoenix Suns organization is thrilled to have the opportunity to support the incredible work of our grant recipients,” said Sarah Krahenbuhl, Executive Director of Phoenix Suns Charities. “In addition to our support for Central High School, the Board chose to award three impact grants to the Girl Scouts, Boys & Girls Clubs of Metro Phoenix and to Jewish Family & Children’s Service. The mission of Phoenix Suns Charities is to support children and family services throughout Arizona and we are proud to be a part of organizations that make our community better every day.” The $100,000 Playmaker grant to Girl Scouts – Arizona Cactus-Pine Council will support The Leadership Center for Girls and Women at Camp Sombrero in South Phoenix. In addition, Boys & Girls Clubs of Metro Phoenix will use the $50,000 grant in the construction of a new gymnasium. And, Jewish Family & Children’s Service will use its $50,000 grant to provide integrated medical and behavioral health services to the Maryvale neighborhood of Phoenix. -

Bisbee, Arizona Field Trip

Mesa Community College urban bicycle tour March 5 & 6, 2011 Trip Leaders: Steve Bass and Philip Clinton FIELD TRIP OBJECTIVES 1. to observe the distribution of human activities and land uses 2. to observe the distribution of biotic, geologic, and atmospheric phenomena 3. to interact with the human and natural environment 4. to gain an appreciation of the diversity of the Phoenix Metropolitan area 5. to build a community of learners in a relaxed setting FIELD TRIP RULES 1. All participants must wear an approved helmet while cycling and a seat belt when traveling by motor vehicle. 2. Use of audio headsets is prohibited while cycling. 3. Participants will travel as a group and stop for discussions along the way. 4. Obey all traffic rules and ride defensively. This is not a race. 5. Pack it in – pack it out. Leave no trash along the route. Itinerary (all times are approximate) Saturday March 5 8 am Depart MCC (arrive by 7:30 am to load gear and to enjoy breakfast) 10 am Snack Break near Camelback Colonnade Mall 12 pm Picnic lunch at Cortez Park 2 pm Arrive at GCC 3 pm Arrive at White Tank Mountain Regional Park 6 pm Dinner Cookout followed by sitting around the campfire & smores Sunday March 6 7 am Breakfast (and stretching) 8 am Depart White Tank Mountain Regional Park by van 9 am Depart GCC by bicycle 10 am Tour the Bharatiya Ekta Mandir Hindu and Jain Temple 12 pm Snack at Encanto Park 1 pm Lunch at South Mountain Community College 3 pm Arrive at MCC 1 SATURDAY ROUTE Begin at the Dobson & Southern campus of Mesa Community College. -

Phoenix, AZ 85003 Telephone: (602) 256-3452 Email: [email protected]

===+ Community Action Plan for South Phoenix, Arizona LOCAL FOODS, LOCAL PLACES TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE November 2018 For more information about Local Foods, Local Places visit: https://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/local-foods-local-places CONTACT INFORMATION: Phoenix, Arizona Contact: Rosanne Albright Environmental Programs Coordinator City Manager’s Office, Office of Environmental Programs 200 W. Washington, 14th Floor Phoenix, AZ 85003 Telephone: (602) 256-3452 Email: [email protected] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Project Contact: John Foster Office of Community Revitalization U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 1200 Pennsylvania Ave. NW (MC 1807T) Washington, DC 20460 Telephone: (202) 566-2870 Email: [email protected] All photos in this document are courtesy of U.S. EPA or its consultants unless otherwise noted. Front cover photo credit (top photo): Rosanne Albright LOCAL FOODS, LOCAL PLACES COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN South Phoenix, Arizona COMMUNITY STORY South Phoenix, Arizona, along with Maricopa County and the greater Phoenix metropolitan area, lies within the Salt River Watershed.1 Despite the shared geohistorical connections to the Salt River, the history and development of South Phoenix is vastly different from the rest of Phoenix. The history of the South Phoenix corridor along the Salt River, generally south of the railroad tracks, is a story of many different people carving out an existence for themselves and their families and persisting despite many extreme challenges. Its historical challenges include extreme poverty in an area that offered primarily low-wage agricultural and some industrial jobs; regional indifference and often hostile racist attitudes that restricted economic opportunities; unregulated land use and relatively late city annexation of a predominantly minority district; lack of investments in housing stock and Figure 1 – Colorful wall mural separating the Spaces of basic infrastructure; and industrialization that engendered Opportunity Farm Park from residential homes. -

Due South Apts.Indd

Investment Property Offering Due South Apartments 8818 S Central Avenue | Phoenix, AZ A 128 Unit Apartment Complex Located in Phoenix, Arizona Bill Hahn Senior Vice President 602 222 5105 – Direct 602 418 9578– Mobile [email protected] Jeffrey Sherman Senior Associate 602 222 5109 – Direct 602 694 1127 – Mobile [email protected] Trevor Koskovich Senior Associate 602 222 5145 – Direct 480 227 7420 - Mobile [email protected] Table of Contents I Executive Summary 1 II Property Photos 3 III Location Maps Aerial - Far 4 Aerial - Birds Eye 5 Parcel Map 6 IV Financial Summary 7 V Comparables Rent 8 Sales 11 VI Appendix Legal Disclaimer www.colliers.com/phoenix Due South Apartments 8818 S Central Avenue | Phoenix, AZ Executive Summary Location 8818 S Central Avenue Phoenix, Arizona 85040 List Price $2,990,000 Price Per Unit $23,359 Price Per Square Foot $50.73 Total Units 128 Building Square Footage 58,944 Number of Buildings 2 Land Acres 3.91 Cross Street Baseline & Central Market Phoenix Year Built 1986 Building Class C HVAC Individual Tax Parcel Number 30045224, -225B, -225C Sub Market South Phoenix Foundation Type Slab Location Class C Number of Stories 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY | COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL | 1 Due South Apartments 8818 S Central Avenue | Phoenix, AZ Executive Summary Amenities shopping centers, and a mixture of older and newer single-family homes. The Amenities include air conditioning, main entrance to South Mountain Park, two swimming pools, a basketball court, the largest municipal park in the United picnic area, and coin operated laundry States, is approximately one mile south facility. -

The Apex on Central

OFFERING MEMORANDUM THE APEX ON CENTRAL THE APEX ON CENTRAL APARTMENTS 40 E. SUNLAND AVE, PHOENIX, AZ 85040 EXCLUSIVELY LISTED BY NORTHMARQ MULTIFAMILY TABLE OF CONTENTS Presented by: PROPERTY INFORMATION ......................................................... 8 NorthMarq Multifamily RENT COMPARABLES ................................................................. 26 Trevor Koskovich Bill Hahn Jesse Hudson PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT VICE PRESIDENT T 602.952.4040 T 602.952.4041 T 602.952.4042 C 480.227.7420 C 602.418.9578 C 480.437.4953 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS ................................................................ 32 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SALES COMPARABLES ............................................................... 34 Visit us online at northmarq.com LOCATION MAPS ......................................................................... 44 Phoenix Office 3200 E. CAMELBACK ROAD, SUITE 253 PHOENIX, AZ 85018 602.955.7100 MULTIFAMILY, MANUFACTURED HOUSING & INVESTMENT SALES THIS DOCUMENT/EMAIL HAS BEEN PREPARED BY NORTHMARQ MULTIFAMILY FOR ADVERTISING AND GENERAL INFORMATION ONLY. NORTHMARQ MULTIFAMILY MAKES NO GUARANTEES, REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, REGARDING THE INFORMATION INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, WARRANTIES OF CONTENT, ACCURACY AND RELIABILITY. ANY INTERESTED PARTY SHOULD UNDERTAKE THEIR OWN INQUIRIES AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION. NORTHMARQ MULTIFAMILY EXCLUDES UNEQUIVOCALLY ALL INFERRED OR IMPLIED TERMS, CONDITIONS AND -

Environmental Racism and the Making of South Phoenix, Arizona, USA

Research in Human Ecology The Geography of Despair: Environmental Racism and the Making of South Phoenix, Arizona, USA Bob Bolin School of Human Evolution and Social Change and International Institute of Sustainability Arizona State University Tempe AZ 85287-2402 USA1 Sara Grineski International Institute of Sustainability and Department of Sociology Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287-4802 USA2 Timothy Collins International Institute of Sustainability and Department of Geography Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287-0104 USA3 Abstract Introduction This paper discusses the historical geographical con- Environmental justice studies over the last decade have struction of a contaminated community in the heart of one of explored the socio-spatial distributions of hazardous indus- the largest and fastest growing Sunbelt cities in the US. Our tries and have provided substantial evidence of a dispropor- focus is on how racial categories and attendant social rela- tionate presence of toxic industries and waste sites in many tions were constructed by Whites, in late 19th and early 20th minority, low income communities in the US (e.g. Lester et century Phoenix, Arizona, to produce a stigmatized zone of al. 2001). Less attention has been given to the social process- racial exclusion and economic marginality in South Phoenix, es that produce these environmental injustices over extended a district adjacent to the central city. We consider how rep- historical periods. Analyses of the historical geographic de- resentations of race were historically deployed to segregate velopment of environmental inequities, particularly the ways people of color, both residentially and economically in the that race and class are imbricated in the production and uses early city. -

Nature's Mysteries

Summer 2012 • Volume 8 • No. 1 Nature’s Mysteries Reflections Reflecting ASU’s ranking as 21st in the world in the biological sciences, School of Life Sciences has forged impactful and far- reaching programs of research, education and outreach. We slip into the laboratory of ASU Professor Bert Jacobs to understand how AIDS-HIV vaccines are developed, then shift to Tanzania to see how science training can change treatment and prevention of disease in rural Africa. We drop in on SOLS alumni Rick Overson, Max Nickerson, Damien Salamone and Christian Lawrence. With Overson, we trek to the Panamanian tropical forest, along with biology doctoral student Clint Penick. Together with budding designers and architects with ASU’s Design School’s traveling studio and the Smithsonian, they develop new eyes for nature and bio- inspired innovation. We trace 40 years of hellbender studies in the Ozarks, which mark the career of Max Nickerson, whose path started with his establishment of the first reptile exhibit in The Phoenix Zoo; and cast our eyes toward Children’s Hospital in Boston and Christian Lawrence, whose research has changed how genetics studies can be done – with zebrafish. But don’t think that our ASU faculty and students aren’t change- makers in our own neighborhoods! Come to South Phoenix and visit the home of Associate Professor Juliet Stromberg and Research Faculty member Matthew Chew, who together have transformed a dilapidated rural sanitarium into a vibrant garden home that argues the concept of native versus invasive species. We also peek in on local hummingbirds, Chiricahua leopard frogs and jackrabbits, with new understanding about the role of behavior, disease and human activity in shaping the environment around us. -

ORAL HISTORY in Our Own Words: Recollections & Reflections Historical League, Inc

Arizona HistorymakersJ* ORAL HISTORY In Our Own Words: Recollections & Reflections Historical League, Inc. 8 2012 BENNIE MONTAGUE GONZALES 1924-2008 1997 Internationally Recognized Southwestern Architect The following is an oral history interview with Bennie M. Gonzales (BG) conducted by Zona D. Lorig (ZL) for Historical League, Inc. on August 2, 1996 at his home in Nogales, Arizona. Transcripts for website edited by members of Historical League, Inc. Original tapes are in the collection of the Arizona Historical Society Museum Library at Papago Park, Tempe, Arizona. ZL: This oral history interview is being conducted with Barnaby "Bennie" M. Gonzales on August 2, 1996 at his home in Nogales, Arizona. Mr. Gonzales was recently named a 1997 Historymaker by Historical League, Inc. of the Central Arizona Division of the Arizona Historical Society. The interviewer is Zona Davis Lorig. Congratulations on receiving the honor of being named a Historymaker, Mr. Gonzales. BG: Thank you. ZL: Please begin by telling us when and where you were born. BG: I was born in Phoenix, Arizona in 1924 at 20th Street just south of Osborn which at that time was our family farm, and was quite a distance from downtown Phoenix. I started school at Creighton Elementary on McDowell Road. We used to walk to Indian School Road and 20th Street to catch the bus to the elementary school. Unfortunately my father had diabetes and he became quite ill. We had some property in Phoenix and we moved when I was six years old. My father died when I was eight and we lived on 16th Street just south of Van Buren on Monroe Street. -

RELOCATION GUIDE Phoenix

Greater Phoenix GreaterRELOCATION GUIDE Phoenix 2007-2008 EDITION 2005-2006 EDITION PHOENIX 4 elcome to Greater Phoenix! Dear Prospective Homeowner, w METRO10 Greater Phoenix is leading the charge to the West’s new 21st Century Maricopa Country: The Valley of the Sun………………. ................................ 4-5 economy, based on the concept of “live, work, play, and progress.” Facts, Challenges and the Future…………………………. .......................... 6-7 Why is the area economy so strong? EAST VALLEY 14 For starters, major corporations continue to move here because they like what Median Housing Costs…………………………………….. ....................... 8-9 our people have to offer. Metropolitan Phoenix……………………………………………... ........... 10-13 We are hard working, diverse, educated, active, and independent. East Valley……………...…………………………………… ................... 14-17 Compared to other Western states, our tax structure is among the lowest in the Northeast Valley……………………………………………. ..................... 18-21 NORTHEAST VALLEY 18 region. West Valley………………………………………………….. ................... 22-25 We live in a consistent year-round temperate climate. In the warmer months, we have nearby mountains and lakes at our disposal. Senior Living………………………………………...……… .................... 26-27 Residential housing is a major plus. The Valley has a wide-range of options that Education………………………………………………...…. .................... 28-33 distinguishes our area as one of the most affordable destinations in the country. Attractions & Cultural Facilities……………………….…. ........................... -

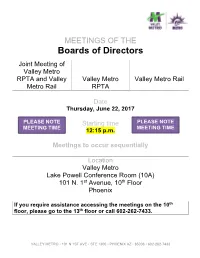

Boards of Directors

MEETINGS OF THE Boards of Directors Joint Meeting of Valley Metro RPTA and Valley Valley Metro Valley Metro Rail Metro Rail RPTA Date Thursday, June 22, 2017 PLEASE NOTE Starting time PLEASE NOTE MEETING TIME 12:15 p.m. MEETING TIME Meetings to occur sequentially Location Valley Metro Lake Powell Conference Room (10A) 101 N. 1st Avenue, 10th Floor Phoenix If you require assistance accessing the meetings on the 10th floor, please go to the 13th floor or call 602-262-7433. VALLEY METRO • 101 N 1ST AVE • STE 1300 • PHOENIX AZ • 85003 • 602-262-7433 PLEASE NOTE MEETING TIME June 15, 2017 Joint Meeting Agenda Valley Metro RPTA and Valley Metro Rail Thursday, June 22, 2017 Lake Powell Conference Room 101 N. 1st Avenue, 10th Floor 12:15 p.m. Action Recommended 1. Items from Citizens Present (yellow card) 1. For information An opportunity will be provided to members of the public at the beginning of the meeting to address the Board on non-agenda items. Up to three minutes will be provided per speaker or a total of 15 minutes for all speakers. 2. Chief Executive Officer’s (CEO) Report 2. For information Scott Smith, CEO, will brief the Boards of Directors on current issues. 3. Minutes 3. For action Minutes from the May 18, 2017 Joint Boards meeting are presented for approval. 4. Public Comment on Agenda Action Items (blue card) 4. For information The public will be provided with an opportunity at this time to address the Boards on all action agenda items. Up to three minutes will be provided per speaker to address all agenda items unless the Chair allows more at his/her discretion.