Caring for Creation G E N E R a L E D I T O R Robert B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

St. Augustine and the Doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ Stanislaus J

ST. AUGUSTINE AND THE DOCTRINE OF THE MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST STANISLAUS J. GRABOWSKI, S.T.D., S.T.M. Catholic University of America N THE present article a study will be made of Saint Augustine's doc I trine of the Mystical Body of Christ. This subject is, as it will be later pointed out, timely and fruitful. It is of unutterable importance for the proper and full conception of the Church. This study may be conveniently divided into four parts: (I) A fuller consideration of the doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, as it is found in the works of the great Bishop of Hippo; (II) a brief study of that same doctrine, as it is found in the sources which the Saint utilized; (III) a scrutiny of the place that this doctrine holds in the whole system of his religious thought and of some of its peculiarities; (IV) some consideration of the influence that Saint Augustine exercised on the development of this particular doctrine in theologians and doctrinal systems. THE DOCTRINE St. Augustine gives utterance in many passages, as the occasion de mands, to words, expressions, and sentences from which we are able to infer that the Church of his time was a Church of sacramental rites and a hierarchical order. Further, writing especially against Donatism, he is led Xo portray the Church concretely in its historical, geographical, visible form, characterized by manifest traits through which she may be recognized and discerned from false chuiches. The aspect, however, of the concept of the Church which he cherished most fondly and which he never seems tired of teaching, repeating, emphasizing, and expound ing to his listeners is the Church considered as the Body of Christ.1 1 On St. -

I. the Work of the Two-Horn Beast of the Earth (Rev. 13:11-15)

The Revelation of Jesus Christ The TRINITY of EVIL: Satan, the Antichrist (Beast of the Sea), and the False Prophet (Beast of the Earth) Revelation 13:11-18 Introduction In last week's study, we were introduced to the "beast of the sea", who is identified as the Antichrist. The Antichrist is empowered by Satan, and eventually rules as a political and military genius over the earth during the second half of the 70th Week of Daniel. The Antichrist will rule the world as the leader of the revived Roman Empire. In today's passage, we are introduced to the "beast of the earth", who is soon identified as the "False Prophet". Whereas the Antichrist is a political and military leader, the False Prophet is a religious leader. The reader is now aware of Satan's unholy trinity. Satan is the counterfeit of God the Father, the Antichrist is the blasphemous counterfeit of the Son, and the False Prophet is the deceptive counterfeit of the Holy Spirit. Like Ahab and Jezebel joined the religious priests of Baal, so the Antichrist and the False Prophet, combine political and religious power to rule over the world. I. The Work of the Two-Horn Beast of the Earth (Rev. 13:11-15) 11 Then I saw another beast coming up out of the earth; and he had two horns like a lamb, and he spoke as a dragon. 12 He exercises all the authority of the first beast in his presence. And he makes the earth and those who live on it worship the first beast, whose fatal wound was healed. -

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and The

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and the Limits of Control in the Information Age Jan W Geisbusch University College London Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Anthropology. 15 September 2008 UMI Number: U591518 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591518 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration of authorship: I, Jan W Geisbusch, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: London, 15.09.2008 Acknowledgments A thesis involving several years of research will always be indebted to the input and advise of numerous people, not all of whom the author will be able to recall. However, my thanks must go, firstly, to my supervisor, Prof Michael Rowlands, who patiently and smoothly steered the thesis round a fair few cliffs, and, secondly, to my informants in Rome and on the Internet. Research was made possible by a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). -

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period This volume is an investigation of how Augustine was received in the Carolingian period, and the elements of his thought which had an impact on Carolingian ideas of ‘state’, rulership and ethics. It focuses on Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims, authors and political advisers to Charlemagne and to Charles the Bald, respectively. It examines how they used Augustinian political thought and ethics, as manifested in the De civitate Dei, to give more weight to their advice. A comparative approach sheds light on the differences between Charlemagne’s reign and that of his grandson. It scrutinizes Alcuin’s and Hincmar’s discussions of empire, rulership and the moral conduct of political agents during which both drew on the De civitate Dei, although each came away with a different understanding. By means of a philological–historical approach, the book offers a deeper reading and treats the Latin texts as political discourses defined by content and language. Sophia Moesch is currently an SNSF-funded postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford, working on a project entitled ‘Developing Principles of Good Govern- ance: Latin and Greek Political Advice during the Carolingian and Macedonian Reforms’. She completed her PhD in History at King’s College London. Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period Political Discourse in Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims Sophia Moesch First published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

The Impact of Pilgrimage Upon the Faith and Faith-Based Practice of Catholic Educators

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators Rachel Capets The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Capets, R. (2018). The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Education)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/219 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE FAITH AND FAITH-BASED PRACTICE OF CATHOLIC EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy, Education The University of Notre Dame, Australia Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P. 23 August 2018 THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE CATHOLIC EDUCATOR Declaration of Authorship I, Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P., declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Education, University of Notre Dame Australia, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. -

Sunday, July 18 9 A.M. – Baptism Class – Pope John

ST. CASPAR CHURCH WAUSEON, OHIO July 18, 2021 Monday, July 19 Nothing scheduled Sunday, July 18 Tuesday, July 20 – St. Apollinaris, Bishop & Martyr 9 a.m. – Baptism Class – Pope John Room 8:30 a.m. for religious vocations 11:30 a.m. – New Parishioner Registration – NW Wednesday, July 21 – St. Lawrence of Brindisi, Priest & Doctor 5 p.m. – Spanish Rosary – South Wing of the Church 8:30 a.m. for all leaders Monday, July 19 Thursday, July 22 – St. Mary Magdalene 7 p.m. – Prayer Group – South Wing 8:30 a.m. for the homeless Friday, July 23 Friday, July 23 – St. Bridget, Religious 6:30 p.m. – Encuentro – North Wing 8:30 a.m. Adolfo Ferriera (1 year) Saturday, July 24 Saturday, July 24 5 p.m. for families 6 p.m. – Rosary – South Wing Chapel Sunday, July 25 – Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary Time 8 a.m. Lynn Keil Sunday, July 25 10:30 a.m. for St. Caspar parishioners 1 p.m. – Baptism – Church 1 p.m. for an end of abortion 5 p.m. – Spanish Rosary – South Wing Notre Dame Academy Seeks Host Families for Saturday, July 24– 5 p.m. International Students Arriving in August! Musicians: Proclaimer: Sally Kovar Do you want to learn more about another Servers: Ann Spieles & Brady Morr culture? Learn a new language, traditions, and food? Comm. Ministers: Roger & Cathy Drummer Then hosting an international student might be right Ushers: Team #1 (Jean LaFountain, Don Davis, Paul for you! Notre Dame Academy is seeking host Murphy) families for the 2021-22 school year. -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

In This Week's Bulletin

CATHOLIC PARISH Diocese of Cleveland May 10, 2015 | Sixth Sunday of Easter IN THIS WEEK’S BULLETIN Parish Directory page 2 Women’s Guild Mother/Daughter Banquet Page 6 Loving God, Beyond We thank you for the love of the mothers you have given us, Driving with Dignity whose love is so precious that it can never be measured, Page 8 whose patience seems to have no end. May we see your loving hand behind them and guiding them. We pray for those mothers who fear they will run out of love or time or patience. We ask you to bless them with your own special love. We ask this in the name of Jesus, our brother. Amen. Saint Ambrose Catholic Parish | 929 Pearl Road, Brunswick, OH 44212 Phone | 330.460.7300 Fax |330.220.1748 Web | www.StAmbrose.us Sunday, May 10 | Mother’s Day THIS WEEK MARK YOUR CALENDARS 8:00 am-12:00 pm KofC Mother’s Day Breakfast (HH) 9:00-10:00 am Children’s Liturgy of the Word (CC) 10:30-11:30 am Children’s Liturgy of the Word (CC) 4:00-5:00 pm pm Cub Scouts (LCJN) Monday, May 11 May Crowning 9:00 am-5:00 pm Eucharistic Adoration (CC) Join Us! 6:00-8:00 pm Divorce Care for Kids (S) 6:00-8:00 pm Divorce Care (S) Tuesday | May 19, 2015 6:30-8:30 pm Scripture Study (LCMK) Time: 7:00pm 7:00-8:30 pm JH PSR Parent Meeting (LCJN) Procession to St. Ambrose Church 7:00-8:30 pm Youth & Young Adult Ministry (LCFM) Reception to follow in Hilkert Hall 7:00-9:00 pm Catholic Works of Mercy (LCMT) Tuesday, May 12 9:00-11:00 am Sarah’s Circle (LCMK) Saint Ambrose Directory 9:30 –11:30 am Ecumenical Women’s Breakfast (PCLMT) Here’s another 11:00 am-12:00 pm Music Ministry | New Life Choir (C) 6:00-8:00 pm CYO Volleyball (HHG) opportunity to have 7:00-8:00 pm Overeaters Anonymous (LCMT) your family picture 7:00-8:00 pm Worship Commission (HH) taken for our Parish 7:00-9:00 pm DBSA (LCJN) Directory! 7:00-9:00 pm Pastoral Council (PLCJP) 7:00-9:00 pm Knights of Columbus (LCFM) Photo Sessions will be held in the Lehner Center on: Wednesday, May 13 9:00-10:00 am Yoga (HH) Wednesday, May 13: 2-9pm 9:30-11:00 am Scripture Study (LCLK) Thursday, May 14: 2-9pm 1:00-2:00 pm Fr. -

Being a Michael Jackson Pilgrim: Dedicated to a Never-Ending Journey

UNIVERSITY OF GRONINGEN Being a Michael Jackson Pilgrim: dedicated to a never-ending journey S2054620 9/15/2015 Fardo Ine Eringa Master thesis Religion and the Public Domain, Faculty of Religious Studies First supervisor: dr. Mathilde van Dijk Second supervisor: dr. Kristin McGee “Heal the world Make it a better place For you and for me And the entire human race There are people dying If you care enough for the living Make a better place For you and for me.” ‘Heal The World’, Michael Jackson (1991) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research has been made possible through invaluable input and support by several individuals. I would like to express my gratitude to all those who have guided me through the writing process of this thesis. First of all, I would like to thank Mathilde van Dijk, who has supported and motivated me both with her broad knowledge in the field of pilgrimage research and with her enthusiasm. During the writing process dr. Van Dijk helped me to structure my study and supported me with extensive feedback. I very much enjoyed our collaboration and it is our personal meetings and dr. Van Dijk’s thorough feedback that have made this study to the best possible outcome. I would also like to thank Kristin McGee, who has been a wonderful second supervisor and has provided me with helpful information in the field of popular culture. Moreover, dr. McGee has provided me with valid feedback both regarding the content of my study and my English. Furthermore, I would like to thank my family for the many brainstorm sessions and their assistance through personal feedback and support during the finalizing of this research. -

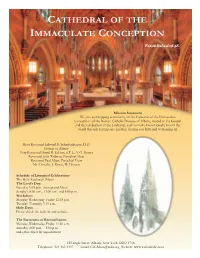

Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception

CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION Established 1848 Mission Statement We, the worshipping community of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany, rooted in the Gospel and the celebration of the Eucharist, seek to make known God’s love in the world through serving one another, sharing our faith and welcoming all. Most Reverend Edward B. Scharfenberger, D.D. Bishop of Albany Very Reverend David R. LeFort, S.T.L., V.G. Rector Reverend John Tallman, Parochial Vicar Reverend Paul Mijas, Parochial Vicar Mr. Timothy J. Kosto, II, Deacon Schedule of Liturgical Celebrations The Holy Eucharist (Mass) The Lord’s Day: Saturday 5:15 p.m. (anticipated Mass) Sunday’s 9:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. Weekdays: Monday-Wednesday-Friday 12:15 p.m. Tuesday-Thursday 7:15 a.m. Holy Days: Please check the bulletin and website. The Sacrament of Reconciliation: Monday-Wednesday-Friday 11:30 a.m. Saturday 4:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. and other times by appointment 125 Eagle Street Albany, New York 12202-1718 Telephone: 518-463-4447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cathedralic.com CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION ALBANY Solemnity of the Epiphany of the Lord On the Sunday of the Epiphany of the Lord, we hear about gifts in the gospel reading. The image of gift is an appropriate one since to- day, on Epiphany Sunday, we acknowledge and celebrate the gift of God’s saving grace offered to everyone in the birth of his Son Je- sus. -

St. Bede & St. Cuthbert

THE PARISH OF St. Bede & St. Cuthbert Parish Priest: Canon Christopher Jackson 0191 388 2302 [email protected] Hospital Chaplain: Fr. Paul Tully 01388 818544 3rd January 2021 (2nd Sunday of Christmas) RIP Tom Walker May he rest in peace, and may his family be consoled by the faith in which he lived and died. COMING TO MASS? You must register if you want to attend Sunday mass either by email [email protected] or by phoning 07396643588; please give your name, phone number, postcode and house number; Registration for a Sunday begins on the previous Monday and ends at 3pm on the Friday. No need to register for weekdays. MASSES THIS WEEK Sunday 9.00 Linda Rowcroft St Bede’s 10.30 People of the Parish St Cuthbert’s Monday 10.00 Jim McGuire St Cuthbert’s Tuesday 11.30 Dr Anthony Hope St Cuthbert’s Wednesday 10.00 FEAST OF THE EPIPHANY St Cuthbert’s People of the Parish Thursday 10.00 Mary Bell St Bede’s Friday 10.00 Olga & Denny Corrigan St Bede’s Saturday 10.00 Deceased Crosby & Mc Loughlin families St Bede’s Sunday 9.00 People of the Parish St Bede’s 10.30 Mary Joseph Flaherty St Cuthbert’s ADORATION OF THE BLESSED SACRAMENT: Wednesday 9.30 St. Cuthbert’s Thursday 9.30 St. Bede’s CONFESSIONS: Wednesday 9.15am - 10 St Cuthbert’s Saturday 9.15am - 10 St Bede’s 0r by arrangement ROSARY: Saturday 9.40am St Bede’s FROM FR CHRIS VERY MANY THANKS for your good kind wishes, cards and gifts this Christmas; may the Christ Child bless you and your family.