Objects Redux

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaverswaver00stocrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Fiber Arts Oral History Series Kay Sekimachi THE WEAVER'S WEAVER: EXPLORATIONS IN MULTIPLE LAYERS AND THREE-DIMENSIONAL FIBER ART With an Introduction by Signe Mayfield Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1993 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kay Sekimachi dated April 16, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

California and the Fiber Art Revolution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 California and the Fiber Art Revolution Suzanne Baizerman Oakland Museum of California, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Baizerman, Suzanne, "California and the Fiber Art Revolution" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 449. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/449 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. California and the Fiber Art Revolution Suzanne Baizerman Imogene Gieling Curator of Crafts and Decorative Arts Oakland Museum of California Oakland, CA 510-238-3005 [email protected] In the 1960s and ‘70s, California artists participated in and influenced an international revolution in fiber art. The California Design (CD) exhibitions, a series held at the Pasadena Art Museum from 1955 to 1971 (and at another venue in 1976) captured the form and spirit of the transition from handwoven, designer textiles to two dimensional fiber art and sculpture.1 Initially, the California Design exhibits brought together manufactured and one-of-a kind hand-crafted objects, akin to the Good Design exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. -

At Long Last Love Press Release

At Long Last Love: Fiber Sculpture Gets Its Due October 2014 It looks as if 2014 will be the year that contemporary fiber art finally gets the recognition and respect it deserves. For us, it kicked off at the Whitney Biennial in May which gave pride of place to Sheila Hicks’ massive cascade, Pillar of Inquiry/Supple Column. Last month saw the opening of the influential Thread Lines, at The Drawing Center in New York featuring work by 16 artists who sew, stitch and weave. Now at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the development of ab- straction and dimensionality in fiber art from the mid-twentieth centu- ry through to the present is examined in Fiber: Sculpture 1960–present from October 1st through January 4, 2015. The exhibition features 50 works by 34 artists, who crisscross generations, nationalities, processes and aesthetics. It is accompanied by an attractive companion volume, Fiber: Sculpture 1960-present available at browngrotta.com. There are some standout works in the exhibition — we were thrilled Fiber: Sculpture 1960 — present opening photo by Tom Grotta to see Naomi Kobayashi’s Ito wa Ito (1980) and Elsi Giauque’s Spatial Element (1989), on loan from European museums, in person after ad- miring them in photographs. Anne Wilson’s Blonde is exceptional and Ritzi Jacobi and Françoise Grossen are represented by strong works, too, White Exotica (1978, created with Peter Jacobi) and Inchworm, respectively. Fiber: Sculpture 1960–present aims to create a sculp- tural dialogue, an art dialogue — not one about craft, ICA Mannion Family Senior Curator Jenelle Porter explained in an opening-night conversation with Glenn Adamson, Director, Museum of Arts and Design. -

Oral History Interview with Anne Wilson, 2012 July 6-7

Oral history interview with Anne Wilson, 2012 July 6-7 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Transcription of this oral history interview was made possible by a grant from the Smithsonian Women's Committee. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Anne Wilson on July 6 and 7, 2012. The interview took place in the artist's studio in Evanston, Illinois, and was conducted by Mija Riedel for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Anne Wilson and Mija Riedel have reviewed the transcript. Their heavy corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MIJA RIEDEL: This is Mija Riedel with Anne Wilson at the artist's studio in Evanston, Illinois, on July 6, 2012, for the Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art. This is disc number one. So, Anne, let's just take care of some of the early biographical information first. You were born in Detroit in 1949? ANNE WILSON: I was. MS. RIEDEL: Okay. And would you tell me your parents' names? MS. -

Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled By: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C

OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C. Wallace Compiled in: June to August 2010 Last Updated: 17-Aug-10 Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 In Celebration of pp. 1-10 Official opening, OCC headquarters, This article is a series of photographs and the Ontario Crafts Crossroads, Joan Chalmers, Thoma Ewen, blurbs detailing the official opening of the Council Tamara Jaworska, Dora de Pedery, Judith OCC, the Crossroads exhibition, and some Almond-Best, Stan Wellington, David behind the scenes with the Council. Reid, Karl Schantz, Sandra Dunn. Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 Hi Fibres '76 p. 12 Exhibition, sculptural works, textile forms, This article details Hi Fibres '76, an OCC Gallery, Deirdre Spencer, Handcraft exhibition of sculptural works and textile House, Lynda Gammon, Madeleine forms in the gallery of the Ontario Crafts Chisholm, Charlotte Trende, Setsuko Council throughout February. Piroche, Bob Polinsky, Evelyn Roth, Charlotte Schneider, Phyllis gerhardt, Dianne Jillings, Joyce Cosgrove, Sue Proom, Margery Powel, Miriam McCarrell, Robert Held. Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 Communications pp. 1-6 First conference, structures and This article discusses the initial Weekend programs, Alan Gregson, delegates. conference of the OCC, in which the structure of the organization, the programs, and the affiliates benefits were discussed. Page 1 of 153 OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 The Affiliates of pp. -

Fiberartoral00lakyrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Gyongy Laky FIBER ART: VISUAL THINKING AND THE INTELLIGENT HAND With an Introduction by Kenneth R. Trapp Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1998-1999 Copyright 2003 by The Regents of the University of California has been Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Gyongy Laky, dated October 21, 1999. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Asma Mohseni, Summer Larson, and Ama Wertz!

SEPTEMBER 2014 NEWSLETTER PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE WHAT’S INSIDE? elcome to our members who joined us recently: Asma Mohseni, WSummer Larson, and Ama Wertz! Please find details to our next th meeting on September 20 in Berkeley in the pages of this newsletter! Our PAGE meeting will be at the home of Master Weaver Jean Pierre Larochette and 1 President’s Message Tapestry Designer and Weaver Yael Larochette’s home for a presentation 2 Next Meeting 3 Reminders on the release of their new book, “The Tree of Lives: Adventures Between 4 Water Water! Warp and Weft.” Thank you to our gracious hosts, Jean Pierre and Yael. 6 Unbroken Web 8 What Happened at THAT Meeting? Hopefully many of you in the area were able to make it to our EBMUD 10 Tapestry Redux Water, Water exhibition this summer. Many thanks to our hard working 12 Member News show committee Alex Friedman, Tricia Goldberg, and Sara Ruddy for 14 Business Info Your TWW Board Members handling all the moving parts, and putting on a wonderful and well attended Membership Dues opening reception! And also a great big thank you to our juror and co- Newsletter Submission Info founding TWW member Joyce Hulbert for curating our work into a lovely exhibition and writing a touching and tasteful text to accompany it. Please Tapestry Weavers West is an organization find Joyce’s words on our show in the pages of this newsletter. with a goal to act as a supporting educational and networking group for tapestry artists. For further details of membership information We will have some business to attend to after Jean Pierre and Yael’s please contact: presentation. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

Progressional Journeys: Compelling New Directions for Three “New Basketry” Artists

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2010 Progressional Journeys: Compelling New Directions for Three “New Basketry” Artists J. Penny Burton University of Missouri, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Burton, J. Penny, "Progressional Journeys: Compelling New Directions for Three “New Basketry” Artists" (2010). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 11. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. PROGRESSIONAL JOURNEYS: COMPELLING NEW DIRECTIONS FOR THREE “NEW BASKETRY” ARTISTS JUDITH PENNEY BURTON [email protected] This paper is based upon and dedicated to three amazing artists and their bodies of work which have inspired me immensely for many years now: Dorothy Gill Barnes, Kay Sekimachi, and Patricia Hickman. This paper is essentially derived from primary research material that was gleaned from Skype and telephone interviews with the artists by the author. The first criterion for selecting these specific women to interview was their major influence upon their peers during the “new basketry” movement, in conjunction with their intense commitment to material engagement in their work. In the end, however, these women were chosen due to the fact that all three are life-long learners who continue to forge along exciting trajectories with their art practices by engaging and blending techniques that they had mastered over the decades in new and exciting ways, often with materials that were new to them. -

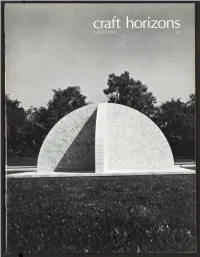

Craft Horizons AUGUST 1973

craft horizons AUGUST 1973 Clay World Meets in Canada Billanti Now Casts Brass Bronze- As well as gold, platinum, and silver. Objects up to 6W high and 4-1/2" in diameter can now be cast with our renown care and precision. Even small sculptures within these dimensions are accepted. As in all our work, we feel that fine jewelery designs represent the artist's creative effort. They deserve great care during the casting stage. Many museums, art institutes and commercial jewelers trust their wax patterns and models to us. They know our precision casting process compliments the artist's craftsmanship with superb accuracy of reproduction-a reproduction that virtually eliminates the risk of a design being harmed or even lost in the casting process. We invite you to send your items for price design quotations. Of course, all designs are held in strict Judith Brown confidence and will be returned or cast as you desire. 64 West 48th Street Billanti Casting Co., Inc. New York, N.Y. 10036 (212) 586-8553 GlassArt is the only magazine in the world devoted entirely to contem- porary blown and stained glass on an international professional level. In photographs and text of the highest quality, GlassArt features the work, technology, materials and ideas of the finest world-class artists working with glass. The magazine itself is an exciting collector's item, printed with the finest in inks on highest quality papers. GlassArt is published bi- monthly and divides its interests among current glass events, schools, studios and exhibitions in the United States and abroad. -

Amie Adelman Professor College of Visual Arts and Design University of North Texas Denton, TX (Photo by Ahna Hubnik)

Fibers in the Art Classroom An Art Educator Highlight Amie Adelman Professor College of Visual Arts and Design University of North Texas Denton, TX (Photo by Ahna Hubnik) When did your personal interest in fiber begin? My maternal grandma taught me how to crochet when I was 7 or 8…I crocheted all the time, I even had a subscription to a crochet journal. I wasn't very good at reading or math, but I could power through those journals! As an adult, I was reintroduced to fiber techniques when I was an undergraduate student at Arizona State University, where I received a BFA in fibers. The first fiber course that I enrolled in was Introduction to Fibers, Vicki Jensen taught the course. On the first day of class she introduced us to basketry (coiling twining/ waling,plaiting); I was immediately hooked and quickly changed my major from painting to fibers. I received a solid foundation in fibers at ASU by working with Janet Taylor in weaving and Clare Verstegen in surface design. I continued working in fibers at the University of Kansas where I received an MFA degree and had the privilege of working with Mary Anne Jordan in surface design and Cynthia Schira in weaving. Give a brief description of the sewing and basketry classes you are teaching. (In Stitches students) This semester I am teaching two new courses at the University of North Texas, In Stitches and Subversive Structures. In Stitches covers hand-embroidery, piecing and machine quilting. Students also gain experience quilting on the APQS computerized longarm quilting machine.