Review Sergei Davidenkov, the Father of Soviet Neurogenetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soviet History in the Gorbachev Revolution: the First Phase*

SOVIET HISTORY IN THE GORBACHEV REVOLUTION: THE FIRST PHASE* R.W. Davies I. THE BACKGROUND The Khrushchev thaw among historians began early in 1956 and continued with retreats and starts for ten years. In the spring of 1956 Burdzhalov, the deputy editor of the principal Soviet historical journal, published a bold article re-examining the role of the Bolshevik party in the spring of 1917, demonstrating that Stalin was an ally of Kamenev's in compromising with the Provisional Government, and presenting Zinoviev as a close associate of en in.' The article was strongly criticised. Burdzhalov was moved to an uninfluential post, though he did manage eventually to publish an important history of the February revolution. The struggle continued; and after Khrushchev's further public denunciation of Stalin at the XXII Party Congress in 1961 there was a great flowering of publica- tions about Soviet history. The most remarkable achievement of these years was the publication of a substantial series of articles and books about the collectivisation of agriculture and 'de-kulakisation' in 1929-30, largely based on party archives. The authors-Danilov, Vyltsan, Zelenin, Moshkov and others- were strongly critical of Politburo policy in that period. Their writings were informed by a rather naive critical conception: they held that the decisions of the XVI Party Conference in April 1929, incorporating the optimum variant of the five-year plan and a relatively moderate pace of collectivisation, were entirely correct, but the November 1929 Central Committee Plenum, which speeded up collectivisation, and the decision to de-kulakise which followed, were imposed on the party by Stalin, who already exercised personal power, supported by his henchmen Molotov and Kaganovich. -

1 Psychiatric Knowledge on the Soviet Periphery: Mental Health And

Psychiatric knowledge on the Soviet periphery: mental health and disorder in East Germany and Czechoslovakia, 1948-1975 Sarah Victoria Marks UCL PhD History of Medicine 1 Plagiarism Statement I, Sarah Victoria Marks confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis traces the development of concepts and aetiologies of mental disorder in East Germany and Czechoslovakia under Communism, drawing on material from psychiatry and its allied disciplines, as well as discourses on mental health in the popular press and Party literature. I explore the transnational exchanges that shaped these concepts during the Cold War, including those with the USSR, China and other countries in the Soviet sphere of influence, as well as engagement with science from the 'West'. It challenges assumptions about the 'pavlovization' and top-down control of psychiatry, demonstrating that researchers were far from isolated from international developments, and were able to draw on a broad range of theoretical models (albeit providing they employed certain political or linguistic man). In turn, the flow of knowledge also occurred from the periphery to the centre. Rather than casting the history of psychiatry as one of the scientific community in opposition to the Party, I explore the methods individuals used to further their professional and personal interests, and examples of psychiatrists who engaged ± whether explicitly or reluctantly ± in the project of building socialism as a consequence. I also address broader questions about the history of psychiatry after 1945, a period which is still overshadowed in the literature by 19th century asylum studies and histories of psychoanalysis. -

Mathematics Education Policy As a High Stakes Political Struggle: the Case of Soviet Russia of the 1930S

MATHEMATICS EDUCATION POLICY AS A HIGH STAKES POLITICAL STRUGGLE: THE CASE OF SOVIET RUSSIA OF THE 1930S ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK, SERGUEI D. KARAKOZOV, AND SERGUEI A. POLIKARPOV Abstract. This chapter is an introduction to our ongoing more comprehensive work on a critically important period in the history of Russian mathematics education; it provides a glimpse into the socio-political environment in which the famous Soviet tradition of mathematics education was born. The authors are practitioners of mathematics education in two very different countries, England and Russia. We have a chance to see that too many trends and debates in current education policy resemble battles around math- ematics education in the 1920s and 1930s Soviet Russia. This is why this period should be revisited and re-analysed, despite quite a considerable amount of previous research [2]. Our main conclusion: mathematicians, first of all, were fighting for control over selection, education, and career development, of young mathematicians. In the harshest possible political environment, they were taking po- tentially lethal risks. 1. Introduction In the 1930s leading Russian mathematicians became deeply in- volved in mathematics education policy. Just a few names: Andrei Kolmogorov, Pavel Alexandrov, Boris Delaunay, Lev Schnirelmann, Alexander Gelfond, Lazar Lyusternik, Alexander Khinchin – they are arXiv:2105.10979v1 [math.HO] 23 May 2021 remembered, 80 years later, as internationally renowned creators of new fields of mathematical research – and they (and many of their less famous colleagues) were all engaged in political, by their nature, fights around education. This is usually interpreted as an idealistic desire to maintain higher – and not always realistic – standards in mathematics education; however, we argue that much more was at stake. -

To Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/800 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. ANZUS and the Early Cold War With and Without Galton Vasilii Florinskii and the Fate of Eugenics in Russia NIKOLAI KREMENTSOV WITH AND WITHOUT GALTON About the Publisher Open Book Publishers is a not-for-profit, scholar-led Open Access academic press and we are dedicated to revolutionising academic publishing, breaking down the barriers of high prices and restricted circulation so that outstanding academic books are available for everyone to read and share. If you believe that knowledge should be available to everyone, you can support our work with a monthly pledge or a one-off donation and become part of the OBP community: https://www.openbookpublish/pledge About the Author Nikolai Krementsov is a Professor at the Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, University of Toronto (Canada). He has published several monographs and numerous articles on various facets of the history of science, medicine, and literature in Russia and the Soviet Union. His latest publications include A Martian Stranded on Earth: Alexander Bogdanov, Blood Transfusions, and Proletarian Science (2011), Revolutionary Experiments: The Quest for Immortality in the Bolshevik Science and Fiction (2014), and The Lysenko Controversy as a Global Phenomenon (2017), 2 vols. (co-edited with William deJong-Lambert). With and Without Galton Vasilii Florinskii and the Fate of Eugenics in Russia Nikolai Krementsov https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Nikolai Krementsov This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). -

Shirak Region Which Was Also After the Great Flood

NOTES: ARAGATSOTN a traveler’s reference guide ® Aragatsotn Marz : 3 of 94 - TourArmenia © 2008 Rick Ney ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - www.TACentral.com a traveler’s reference guide ® Aragatsotn Marz : 4 of 94 - TourArmenia © 2008 Rick Ney ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - www.TACentral.com a traveler’s reference guide ® soil surprisingly rich when irrigated. Unlike Talin INTRODUCTIONB Highlights the Southeast has deeper soils and is more heavily ARAGATSOTN marz Area: 2753 sq. km farmed. The mountain slopes receive more rainfall Population: 88600 ²ð²¶²ÌàîÜ Ù³ñ½ then on the plateau and has thick stands of Marz Capital: Ashtarak • Visit Ashtarak Gorge and the three mountain grass and wildflowers throughout the sister churches of Karmravor, B H Distance from Yerevan: 22 km By Rick Ney summer season. Tsiranavor and Spitakavor (p. 10)H MapsB by RafaelH Torossian Marzpetaran: Tel: (232) 32 368, 32 251 EditedB by BellaH Karapetian Largest City: Ashtarak • Follow the mountain monastery trail to Aragatsotn (also spelled “Aragadzotn”) is named Tegher (pp. 18),H Mughni (p 20),H TABLEB OF CONTENTS Hovhanavank (pp. 21)H and after the massive mountain (4095m / 13,435 ft.) that hovers over the northern reaches of Armenia. Saghmosavank (pp. 23)H INTRODUCTIONH (p. 5) The name itself means ‘at the foot of’ or ‘the legs NATUREH (p. 6) • See Amberd Castle, summer home for of’ Aragats, a fitting title if ever there was one for DOH (p. 7) Armenia’s rulers (p 25)H this rugged land that wraps around the collapsed WHEN?H (p. 8) volcano. A district carved for convenience, the • Hike up the south peak of Mt. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title From Truth to Time: Soviet Central Television, 1957-1985 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2702x6wr Author Evans, Christine Elaine Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California From Truth to Time: Soviet Central Television, 1957-1985 By Christine Elaine Evans A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair Professor Victoria Frede Professor Olga Matich Spring 2010 From Truth to Time: Soviet Central Television, 1957-1985 © 2010 By Christine Elaine Evans Abstract From Truth to Time: Soviet Central Television, 1957-1985 by Christine Elaine Evans Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair The Brezhnev era (1964-1982) was also the era of television. The First Channel of Moscow’s Central Television Studio began to reach all eleven Soviet time zones in the same years, 1965-1970, that marked the beginning of a new political era, the period of decline, corruption, and cynicism, but also stability, relative prosperity, and vibrant popular culture, that came to be called, retrospectively, the “era of stagnation.” Nearly all of the iconic images and sounds of this period were mediated by television: Brezhnev’s slurred speech and corpselike appearance, the singing of Iosif Kobzon and Alla Pugacheva, the parades and funerals on Red Square, and Olympic figure skating, to name just a few. Quotations and jokes drawn from specific TV movies and shows are ubiquitous in post-Soviet memoirs and the press. -

On Labels and Issues: the Lysenko Controversy and the Cold War

Journal of the History of Biology (2012) 45:373–388 Ó Springer 2011 DOI 10.1007/s10739-011-9292-6 On Labels and Issues: The Lysenko Controversy and the Cold War WILLIAM DEJONG-LAMBERT City University of New York Bronx, NY USA E-mail: [email protected] WILLIAM DEJONG-LAMBERT Harriman Institute of Russian Eurasian and Eastern European Studies at Columbia University New York, NY USA NIKOLAI KREMENTSOV University of Toronto Toronto, ON Canada E-mail: [email protected] The early years of the Cold War were marked by vicious propaganda and counter-propaganda campaigns that thundered on both sides of the Iron Curtain, further dividing the newly formed ‘‘Western’’ and ‘‘Eastern’’ blocs. These campaigns aimed at the consolidation and mobilization of each camp’s politics, economy, ideology, and culture, and at the vilification and demonization of the opposite camp. One of the most notorious among these campaigns – ‘‘For Michurinist biol- ogy’’ and ‘‘Against Lysenkoism,’’ as it became known in Eastern and Western blocs respectively – clearly demonstrated that the Cold War drew the dividing line not only on political maps, but also on science. The centerpiece of the campaign was a session on ‘‘the situation in biological science’’ held in the summer of 1948 by the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences (VASKhNIL) in Moscow. In his opening address on July 31, the academy’s president Trofim D. Lysenko stated that modern biology had diverged into two opposing trends. Lysenko and his disciples represented one trend, which -

SHEIKH (Somewhat Hard Examination of In-Depth Knowledge of History): "History Is a Nightmare from Which I Am Trying to Awake

SHEIKH (Somewhat Hard Examination of In-Depth Knowledge of History): "History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake. Writing this set isn’t helping." Questions by Will Alston and Jordan Brownstein Packet 1 1. Historians such as Howard Dorgan, who created an Encyclopedia of this region, tend to define it more narrowly than a federal agency which uses a definition of it based on economic performance, and which was created partly in response to Harry Caudill’s writings. Benton MacKaye popularized the idea of creating a landmark that connects most of this region. Inspired by reformers like Jane Addams, missionaries established “settlement schools” like Pine Mountain within this region to change its culture. Conflict with Quakers led to this region being largely settled by (*) Scotch-Irish immigrants, who developed a special type of dulcimer. As part of the Great Society, a federal Regional Commission was established to promote development in this region, where westward-moving settlers often passed through the Cumberland Gap. For 10 points, identify this U.S. cultural region from which bluegrass originated, which is traversed by a major mountain trail. ANSWER: Appalachia 2. In June 2009, this man’s family was awarded $15.5 million in a case brought in the U.S. under the Alien Tort Statute. After the murder of four chiefs, this man was arrested along with Paul Levera and seven others, with whom he formed an ethnic group’s “Nine.” This man wrote the memoir A Month and a Day recounting his detention by the government of Ibrahim Babangida. This leader of the (*) Movement of the Survival of the Ogoni People led protests against land degradation due to the policies of Royal Dutch Shell, which prompted the government of Sani Abacha to have him put on show trial. -

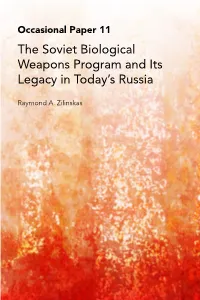

The Soviet Biological Weapons Program and Its Legacy in Today's

Occasional Paper 11 The Soviet Biological Weapons Program and Its Legacy in Today’s Russia Raymond A. Zilinskas Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction National Defense University MR. CHARLES D. LUTES Director MR. JOHN P. CAVES, JR. Deputy Director Since its inception in 1994, the Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD Center) has been at the forefront of research on the implications of weapons of mass destruction for U.S. security. Originally focusing on threats to the military, the WMD Center now also applies its expertise and body of research to the challenges of homeland security. The Center’s mandate includes research, education, and outreach. Research focuses on understanding the security challenges posed by WMD and on fashioning effective responses thereto. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff has designated the Center as the focal point for WMD education in the joint professional military education system. Education programs, including its courses on countering WMD and consequence management, enhance awareness in the next generation of military and civilian leaders of the WMD threat as it relates to defense and homeland security policy, programs, technology, and operations. As a part of its broad outreach efforts, the WMD Center hosts annual symposia on key issues bringing together leaders and experts from the government and private sectors. Visit the center online at http://wmdcenter.ndu.edu. The Soviet Biological Weapons Program and Its Legacy in Today’s Russia Raymond A. Zilinskas Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction Occasional Paper, No. 11 National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. -

Alexei Kojevnikov Alexei Kojevnikov Since 1948, the Lysenko Case Has Become Generally Known As the Symbol of the Ideological

GAMES OF SOVIET DEMOCRACY IDEOLOGICAL DISCUSSIONS IN SCIENCES AROUND 1948 RECONSIDERED. Alexei Kojevnikov* Alexei Kojevnikov Alexei Kojevnikov Since 1948, the Lysenko case has become generally known as the symbol of the ideological dic- tate in science and its damaging consequences. It is often explained that in the years following World War II, the Stalinist leadership launched an ideological and nationalistic campaign aimed at the creation of Marxist-Leninist and/or distinctively Russian, non-Western science. Concepts and theories which were found idealistic or bourgeois were banned and their supporters si- lenced. In no other science was this process completed to the same degree as in biology after the infamous Session of the Soviet Academy of Agricultural Sciences in August 1948, at which Lysenko declared the victory of his "Michurinist biology" over presumably idealistic "formal" genetics. The August Session, in turn, served as the model for a number of other ideological dis- cussions in various scholarly disciplines. This widely accepted interpretation encounters, however, two serious difficulties. The first ari- ses from a selective focus on one particular debate which fits stereotypes the best. It was critics of the Stalinist system who singled out the Lysenko case as the most important example of the application of Soviet ideology to science. The communist party viewed it differently. It did re- gard the event as a major achievement of the party ideological work and a great contribution to the progress of science (until 1964 when the mistake was quietly acknowledged). But what is more interesting and less expected, is that communists claimed five main ideological successes in science rather than one. -

The Upsurge of Irrationality. Post-Truth Politics for a Polarised World

The upsurge of irrationality. Post-truth politics for a polarised world ANGELO FASCE ABSTRACT WORK TYPE Firstly, I summarise the current philosophical and psychological study of Article post-truth. Secondly, I discuss “white post-truth”, a still unattended form perceived as morally superior by many social actors and scholars. Thirdly, I ARTICLE HISTORY describe the kind of intergroup struggle that underlies the emergence and Received: spread of these non-standard epistemologies. 13–April–2019 Accepted: 10–June–2019 Published Online: 24–November–2019 ARTICLE LANGUAGE English/Spanish KEYWORDS Post-truth Polarization Unwarranted Beliefs Pseudoscience Science Denialism Intergroup Anxiety © Studia Humanitatis – Universidad de Salamanca 2020 A. Fasce (✉) Disputatio. Philosophical Research Bulletin Universitat de València, Spain Vol. 9, No. 13, Jun. 2020, pp. 0-00 e-mail: [email protected] ISSN: 2254-0601 | www.disputatio.eu © The author(s) 2020. This work, published by Disputatio [www.disputatio.eu], is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License [BY–NC–ND]. The copy, distribution and public communication of this work will be according to the copyright notice (https://disputatio.eu/info/copyright/). For inquiries and permissions, please email: (✉) [email protected]. 2 | ANGELO FASCE The upsurge of irrationality. Post-truth politics for a polarised world ANGELO FASCE URRENT SOCIAL POLARISATION has led to an upsurge of collective irrationality in which formerly underground unwarranted beliefs and C radical discourses have become mainstream. Therefore, intergroup struggles often goes one step further than the typical axiological level, so controverted shared values have been replaced by alternative epistemologies shaped by identity-related empirical misconceptions that are at the core of current cases of “culture war” (Kahan, Braman, Slovic, Gastil, & Cohen, 2007). -

With and Without Galton Vasilii Florinskii and the Fate of Eugenics in Russia

With and Without Galton Vasilii Florinskii and the Fate of Eugenics in Russia Nikolai Krementsov Publisher: Open Book Publishers Year of publication: 2018 Published on OpenEdition Books: 21 March 2019 Serie: OBP collection Electronic ISBN: 9791036525063 http://books.openedition.org Printed version ISBN: 9781783745111 Number of pages: xxvi + 668 Electronic reference KREMENTSOV, Nikolai. With and Without Galton: Vasilii Florinskii and the Fate of Eugenics in Russia. New edition [online]. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2018 (generated 04 mai 2019). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/obp/7333>. ISBN: 9791036525063. © Open Book Publishers, 2018 Creative Commons - Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported - CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 WITH AND WITHOUT GALTON About the Publisher Open Book Publishers is a not-for-profit, scholar-led Open Access academic press and we are dedicated to revolutionising academic publishing, breaking down the barriers of high prices and restricted circulation so that outstanding academic books are available for everyone to read and share. If you believe that knowledge should be available to everyone, you can support our work with a monthly pledge or a one-off donation and become part of the OBP community: https://www.openbookpublish/pledge About the Author Nikolai Krementsov is a Professor at the Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, University of Toronto (Canada). He has published several monographs and numerous articles on various facets of the history of science, medicine, and literature in Russia and the Soviet Union. His latest publications include A Martian Stranded on Earth: Alexander Bogdanov, Blood Transfusions, and Proletarian Science (2011), Revolutionary Experiments: The Quest for Immortality in the Bolshevik Science and Fiction (2014), and The Lysenko Controversy as a Global Phenomenon (2017), 2 vols.