Alternative Formats If You Require This Document in an Alternative Format, Please Contact: [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Text in Pdf Format

Vol. 3: 41–50, 2008 AQUATIC BIOLOGY Printed August 2008 doi: 10.3354/ab00062 Aquat Biol Published online July 1, 2008 OPEN ACCESS Effects of water temperature, salinity and feeding regimes on metamorphosis, growth and otolith Sr:Ca ratios of Megalops cyprinoides leptocephali Hui-Lun Chen1, Kang-Ning Shen1, Chih-Wei Chang3, 4, Yoshiyuki Iizuka5, Wann-Nian Tzeng1, 2,* 1Institute of Fisheries Science, and 2Department of Life Science, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan 106, ROC 3National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium, Pingtung, Taiwan 944, ROC 4Institute of Marine Biodiversity and Evolution, National Donghwa University, Hualien, Taiwan 974, ROC 5Institute of Earth Sciences, Academia Sinica, Nankang, Taipei, Taiwan 115, ROC National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan 106, ROC ABSTRACT: We examined the effects of water temperature, salinity and feeding regime on lepto- cephalus metamorphosis, and on daily growth increment deposition and strontium:calcium (Sr:Ca) ratios of otoliths in the Pacific tarpon Megalops cyprinoides. The tarpons at the pre-metamorphic lep- tocephalus stage (SI) were collected in the estuary, marked with tetracycline and then reared for 18 and 30 d in 2 independent experiments with different temperatures (20, 25 and 30°C), salinities (0, 10 and 35) and feeding regimes (fed and starved)—environmental conditions that the fish may experi- ence in the wild. Temporal changes in Sr:Ca ratios from the primordium to the otolith edge of the reared tarpon were examined with an electron probe microanalyzer. At the optimal temperature (25°C) in Expt I, the leptocephalus completed metamorphosis (SII and SIII) after ca. 2 wk irrespective of being fed or starved and reared in low (10) or high (35) salinity, although both somatic and otolith growth rates were lower in starved than in fed groups. -

Skates and Rays Diversity, Exploration and Conservation – Case-Study of the Thornback Ray, Raja Clavata

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS DEPARTAMENTO DE BIOLOGIA ANIMAL SKATES AND RAYS DIVERSITY, EXPLORATION AND CONSERVATION – CASE-STUDY OF THE THORNBACK RAY, RAJA CLAVATA Bárbara Marques Serra Pereira Doutoramento em Ciências do Mar 2010 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS DEPARTAMENTO DE BIOLOGIA ANIMAL SKATES AND RAYS DIVERSITY, EXPLORATION AND CONSERVATION – CASE-STUDY OF THE THORNBACK RAY, RAJA CLAVATA Bárbara Marques Serra Pereira Tese orientada por Professor Auxiliar com Agregação Leonel Serrano Gordo e Investigadora Auxiliar Ivone Figueiredo Doutoramento em Ciências do Mar 2010 The research reported in this thesis was carried out at the Instituto de Investigação das Pescas e do Mar (IPIMAR - INRB), Unidade de Recursos Marinhos e Sustentabilidade. This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) through a PhD grant (SFRH/BD/23777/2005) and the research project EU Data Collection/DCR (PNAB). Skates and rays diversity, exploration and conservation | Table of Contents Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. i List of Tables ............................................................................................................................. v List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................. viii Agradecimentos ........................................................................................................................ -

The Diet of Conger Conger (L

THE DIET OF CONGER CONGER (L. 1758) IN THE DEEP-WATERS OF EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN SEA Anastasopoulou A., Mytilineou Ch., Lefkaditou E., Kavadas S., Bekas P., Smith C.J., Papadopoulou K.N., Dogramatzi K. , Papastamou N. Inst. of Marine Biological Resources, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, 46.7 km Athens-Sounio, Mavro Lithari P.O. BOX 712, 19013 Anavissos, Attica, Greece, [email protected] Abstract The diet of European conger eel Conger conger was investigated for the first time in the Eastern Ionian Sea from specimens collected during experimental bottom long line fishing. Sampling was carried out of Cephalonia Island in deep waters ranging from 300 to 855 m depth in summer and autumn 2010. European conger eel diet was dominated by Fish. Natantia and Brachyura Crustacea were identified as secondary preys, while Cephalopoda, Sipunculida and Isopoda represented accidental preys. C. conger exhibits a benthopelagic feeding behavior as it preys upon both demersal and mesopelagic taxa. The high values of Vacuity index and the low stomach and intestine fullness indicated that the feeding intensity of C. conger in the deep-water of Eastern Ionian Sea was quite low. Larger individuals showed more intense feeding activity and consume larger preys than smaller ones. However, no statistically significant differences were detected in the diet composition and feeding intensity of the species between seasons or size groups. Keywords: European conger eel, stomach analysis, intestine analysis, feeding, Ionian Sea. Η ΔΙΑΤΡΟΦΗ ΤΟΥ CONGER CONGER (L. 1758) ΣΤΑ ΒΑΘΙΑ ΝΕΡΑ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΙΚΗΣ ΜΕΣΟΓΕΙΟΥ ΘΑΛΑΣΣΑΣ Αναστασοπούλου Α., Μυτηλιναίου Χ., Λευκαδίτου Ε., Καβαδδάς Σ., Μπέκας Π., Smith C.J., Παπαδοπούλου Κ., Ντογραμματζή Κ., Παπαστάμου Ν. -

Fisheries Overview, Including Mixed-Fisheries Considerations

ICES Fisheries Overviews Bay of Biscay and Iberian Coast ecoregion Published 30 November 2020 Version 2: 3 December 2020 6.2 Bay of Biscay and Iberian Coast ecoregion – Fisheries overview, including mixed-fisheries considerations Table of contents Executive summary .................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Definition of the ecoregion ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 Mixed-fisheries considerations Bay of Biscay .......................................................................................................................... 2 Mixed-fisheries considerations Iberian waters ...................................................................................................................... 10 Who is fishing ........................................................................................................................................................................ 18 Catches over time .................................................................................................................................................................. 21 Description of the fisheries .................................................................................................................................................... 23 Fisheries management measures ......................................................................................................................................... -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015

Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015 Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015 Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015 Patrícia Amorim | Fishery Analyst, Systems Division | [email protected] Megan Westmeyer | Fishery Analyst, Strategy Communications and Analyze Division | [email protected] CITATION Amorim, P. and M. Westmeyer. 2016. Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015. Sustainable Fisheries Partnership Foundation. 18 pp. Available from www.fishsource.com. PHOTO CREDITS left: Image courtesy of Pedro Veiga (Pedro Veiga Photography) right: Image courtesy of Pedro Veiga (Pedro Veiga Photography) © Sustainable Fisheries Partnership February 2016 KEYWORDS Developing countries, FAO, fisheries, grouper, improvements, seafood sector, small-scale fisheries, snapper, sustainability www.sustainablefish.org i Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The goal of this report is to provide a brief overview of the current status and trends of the snapper and grouper seafood sector, as well as to identify the main gaps of knowledge and highlight areas where improvements are critical to ensure long-term sustainability. Snapper and grouper are important fishery resources with great commercial value for exporters to major international markets. The fisheries also support the livelihoods and food security of many local, small-scale fishing communities worldwide. It is therefore all the more critical that management of these fisheries improves, thus ensuring this important resource will remain available to provide both food and income. Landings of snapper and grouper have been steadily increasing: in the 1950s, total landings were about 50,000 tonnes, but they had grown to more than 612,000 tonnes by 2013. -

Mercury Info Sheet

Methyl Mercury The danger from the sea Report by SHARKPROJECT International • Aug. 31, 2008 Updated by Shark Safe Network Sept. 12, 2009 ! SHARK MEAT CONTAINS HIGH LEVELS OF METHYL MERCURY: A DANGEROUS NEUROTOXIN In the marine ecosystem sharks are on top of the food chain. Sharks eat other contaminated fish and accumulate all of the toxins that they’ve absorbed or ingested during their lifetimes. Since mercury is a persistent toxin, the levels keep building at every increasing concentrations on the way up the food chain. For this reason sharks can have levels of mercury in their bodies that are 10,000 times higher than their surrounding environment. Many predatory species seem to manage high doses of toxic substances quite well. This is not the case, however, with humans on whom heavy metal contamination takes a large toll. Sharks at the top end of the marine food chain are the final depots of all the poisons of the seas. And Methyl Mercury is one of the biologically most active and most dangerous poisons to humans. Numerous scientific publications have implicated methyl mercury as a highly dangerous poison. Warnings from health organizations to children and pregnant women to refrain from eating shark and other large predatory fish, however, have simply not been sufficient, since this “toxic food-information” is rarely provided at the point of purchase. Which Fish Have the Highest Levels of Methyl Mercury? Predatory fish with the highest levels of Methyl Mercury include Shark, King Mackerel, Tilefish and Swordfish. Be aware that shark is sold under various other names, such as Flake, Rock Salmon, Cream Horn, Smoked Fish Strips, Dried cod/stockfish, Pearl Fillets, Lemonfish, Verdesca (Blue Shark), Smeriglio (Porbeagle Shark), Palombo (Smoothound), Spinarolo (Spiny Dogfish), and as an ingredient of Fish & Chips or imitation crab meat. -

On the Occurrence of the Arrowhead Dogfish, Deania Profundorum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sapientia On the occurrence of the arrowhead dogfish, Deania profundorum (Chondrichthyes: Squalidae) off southern Portugal, with a missing gill slit by Rui COELHO & Karim ERZINI (1) R É S U M É. - Signalement d’un Deania pro f u n d o ru m ( C h o n d r i c h- thyes : Squalidae) capturé dans le sud du Portugal, avec absence d’une fente branchiale. Dans ce travail, nous rapportons la capture d’un chien de mer pointe de flèche, Deania pro f u n d o ru m (Smith & Radcliffe, 1912), dans les eaux portugaises méridionales. Le spécimen, une grande femelle mature de 87,5 cm de longueur totale, n’avait que quatre fentes branchiales du côté droit, sans présenter de cicatrice à l’en- droit où la cinquième fente aurait dû se situer. Des mesures compa- ratives entre les tailles des fentes branchiales gauches et droites amènent à conclure que la fente manquante est probablement la première. Key words. - Chondrichthyes - Squalidae - Deania pro f u n d o ru m - ANE - Southern Portugal - Gill slit deformation - Record. The arrowhead dogfish, Deania pro f u n d o ru m (Smith & Rad- cliffe, 1912), is a squalid shark characterized by a greatly elongated snout, that is spatulate dorsal-ventrally and thin-depressed laterally (Compagno, 1984). This is a widely distributed species found on Figure 1. - Map of the southwest coast of Portugal with location of the cap- both sides of the Atlantic, from the Western Sahara to South A f r i c a ture ( ) of the Deania pro f u n d o ru m specimen. -

Using Molecular Identification of Ichthyoplankton to Monitor

Molecular Identification of Ichthyoplankton in Cabo Pulmo National Park 1 Using molecular identification of ichthyoplankton to monitor 2 spawning activity in a subtropical no-take Marine Reserve 3 4 5 6 Ana Luisa M. Ahern1, *, Ronald S. Burton1, Ricardo J. Saldierna-Martínez2, Andrew F. Johnson1, 7 Alice E. Harada1, Brad Erisman1,4, Octavio Aburto-Oropeza1, David I. Castro Arvizú3, Arturo R. 8 Sánchez-Uvera2, Jaime Gómez-Gutiérrez2 9 10 11 12 1Marine Biology Research Division, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California 13 San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA 14 2Departamento de Plancton y Ecología Marina, Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, 15 Instituto Politécnico Nacional, CP 23096, La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico 16 3Cabo Pulmo National Park, Baja California Sur, Mexico 17 4The University of Texas at Austin, Marine Science Institute, College of Natural Sciences, 18 Port Aransas, Texas, USA 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 *Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Molecular Identification of Ichthyoplankton in Cabo Pulmo National Park 26 ABSTRACT: Ichthyoplankton studies can provide valuable information on the species richness 27 and spawning activity of fishes, complementing estimations done using trawls and diver surveys. 28 Zooplankton samples were collected weekly between January and December 2014 in Cabo 29 Pulmo National Park, Gulf of California, Mexico (n=48). Fish larvae and particularly eggs are 30 difficult to identify morphologically, therefore the DNA barcoding method was employed to 31 identify 4,388 specimens, resulting in 157 Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) corresponding 32 to species. Scarus sp., Halichoeres dispilus, Xyrichtys mundiceps, Euthynnus lineatus, 33 Ammodytoides gilli, Synodus lacertinus, Etrumeus acuminatus, Chanos chanos, Haemulon 34 flaviguttatum, and Vinciguerria lucetia were the most abundant and frequent species recorded. -

MECOSTA Phd Thesis 2014

UNIVERSIDADE DO ALGARVE BYCATCH AND DISCARDS OF COMMERCIAL TRAWL FISHERIES IN THE SOUTH COAST OF PORTUGAL Maria Esmeralda de Sá Leite Correia da Costa Tese para obtenção do Grau de Doutor Doutoramento em Ciências e Tecnologias das Pescas (Especialidade em Biologia Pesqueira) Trabalho efectuado sob a orientação de: Professora Doutora Teresa Cerveira Borges 2014 UNIVERSIDADE DO ALGARVE BYCATCH AND DISCARDS OF COMMERCIAL TRAWL FISHERIES IN THE SOUTH COAST OF PORTUGAL Maria Esmeralda de Sá Leite Correia da Costa Tese para obtenção do Grau de Doutor Doutoramento em Ciências e Tecnologias das Pescas (Especialidade em Biologia Pesqueira) Trabalho efectuado sob a orientação de: Professora Doutora Teresa Cerveira Borges 2014 BYCATCH AND DISCARDS OF COMMERCIAL TRAWL FISHERIES IN THE SOUTH COAST OF PORTUGAL Declaração de autoria de trabalho Declaro ser autora deste trabalho, que é original e inédito. Autores e trabalhos consultados estão devidamente citados no texto e constam da listagem de referências incluída. Maria Esmeralda de Sá Leite Correia da Costa Copyright © Maria Esmeralda de Sá Leite Correia da Costa A Universidade do Algarve tem o direito, perpétuo e sem limites geográficos, de arquivar e publicitar este trabalho através de exemplares impressos reproduzidos em papel ou de forma digital, ou por qualquer outro meio conhecido ou que venha a ser inventado, de o divulgar através de repositórios científicos e de admitir a sua cópia e distribuição com objetivos educacionais ou de investigação, não comerciais, desde que seja dado crédito ao autor e editor. Cover image: Bycatch @ Mercator Media adapted by Maria Borges À minha filha Rita, ser de luz , que veio dar à minha vida uma nova força, energia e razão de viver. -

Addressing Demersal Fish Species in Turkey

CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF DEMERSAL FISHERY: ADDRESSING DEMERSAL FISH SPECIES IN TURKEY 1DIDEM GOKTURK, 2TOMRIS DENIZ 1,2Istanbul University, Faculty of Fisheries, Department of Fisheries Technology 34470 Laleli-Istanbul, Turkey Email: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: Marine capture fisheries have an important issue in the total fisheries for Turkey with its favourable geographic position and surrounded by four seas. The depletion of fish stocks from global fisheries has been a long-standing concern. Incidental catch of non-target (termed by-catch and discard) species also has been drawing great interest in proposed conservation issue. Effects of fisheries, especially demersal fisheries for economically important fish species, on the ecosystem have also been monitored for a long time. Due to the nature of commercial fishing operations it needs to be a reasonable management. In this study, demersal fisheries of Turkey are tried to be evaluated in terms of demersal fish species. Keywords: Fisheries management, demersal fisheries, demersal fish species, Mediterranean basin, Turkey. I. INTRODUCTION food source. Total marine landings have been reported as 81.5 million tonnes in the world obtaining Turkey is surrounded by four seas having different from fisheries sources in 2014 [1]. The protection and characteristic with high biodiversity and has also sustainability of these important food resources can important fishing grounds. These are the Black Sea, only be ensured by optimum fisheries management Sea of -

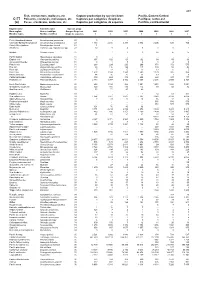

Fish, Crustaceans, Molluscs, Etc Capture Production by Species

489 Fish, crustaceans, molluscs, etc Capture production by species items Pacific, Eastern Central C-77 Poissons, crustacés, mollusques, etc Captures par catégories d'espèces Pacifique, centre-est (a) Peces, crustáceos, moluscos, etc Capturas por categorías de especies Pacífico, centro-oriental English name Scientific name Species group Nom anglais Nom scientifique Groupe d'espèces 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Nombre inglés Nombre científico Grupo de especies t t t t t t t Pink(=Humpback)salmon Oncorhynchus gorbuscha 23 0 - - - - - - Chinook(=Spring=King)salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha 23 1 193 2 416 3 278 2 992 2 205 538 724 Coho(=Silver)salmon Oncorhynchus kisutch 23 1 - - - - - - Smelts nei Osmerus spp, Hypomesus spp 23 12 8 4 5 1 0 1 Milkfish Chanos chanos 25 ... 1 2 3 14 15 15 Pacific halibut Hippoglossus stenolepis 31 0 - - - - - - English sole Pleuronectes vetulus 31 197 102 63 102 69 59 66 Arrow-tooth flounder Atheresthes stomias 31 0 1 5 2 3 2 3 Petrale sole Eopsetta jordani 31 268 224 220 266 371 372 575 Rex sole Glyptocephalus zachirus 31 98 116 124 117 109 54 42 Rock sole Lepidopsetta bilineata 31 7 13 15 13 13 6 5 Dover sole Microstomus pacificus 31 1 403 1 994 1 943 1 590 1 179 826 864 Pacific sand sole Psettichthys melanostictus 31 44 35 27 22 19 7 6 California flounder Paralichthys californicus 31 389 424 379 456 422 327 177 Flatfishes nei Pleuronectiformes 31 2 383 1 977 2 442 2 367 2 236 2 599 2 324 North Pacific hake Merluccius productus 32 853 1 194 988 1 091 1 651 1 683 1 651 Grenadiers, rattails nei Macrouridae 32 145 156 130 114 99 58 82 Gadiformes nei Gadiformes 32 53 71 47 40 - - - Hagfishes nei Myxinidae 33 - - - 1 54 68 302 Sea catfishes nei Ariidae 33 1 964 2 161 1 097 1 287 3 948 4 174 4 056 Squirrelfishes nei Holocentridae 33 0 24 22 18 15 12 16 Flathead grey mullet Mugil cephalus 33 ..