Unit 3 Caste

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

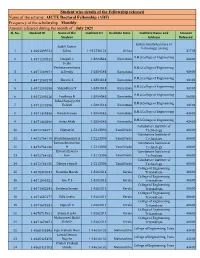

Student Wise Details of the Fellowship Released Name of the Scheme

Student wise details of the Fellowship released Name of the scheme: AICTE Doctoral Fellowship (ADF) Frequency of the scholarship –Monthly Amount released during the month of : July 2021 Sl. No. Student ID Name of the Institute ID Institute State Institute Name and Amount Student Address Released Indira Gandhi Institute of Sushil Kumar Technology, Sarang 1 1-4064399722 Sahoo 1-412736121 Orissa 31703 B.M.S.College of Engineering 2 1-4071237529 Deepak C 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Perla Venkatasreenivasu B.M.S.College of Engineering 3 1-4071249071 la Reddy 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 4 1-4071249170 Shruthi S 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 5 1-4071249196 Vidyadhara V 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 6 1-4071249216 Pruthvija B 1-5884543 Karnataka 86800 Tulasi Naga Jyothi B.M.S.College of Engineering 7 1-4071249296 Kolanti 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 8 1-4071448346 Manali Raman 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 9 1-4071448396 Anisa Aftab 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Coimbatore Institute of 10 1-4072764071 Vijayan M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 11 1-4072764119 Sivasubramani P A 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Ramasubramanian Coimbatore Institute of 12 1-4072764136 M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Eswara Eswara Coimbatore Institute of 13 1-4072764153 Rao 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 14 1-4072764158 Dhivya Priya N 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 -

Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of Higher Education

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2276 TO BE ANSWERED ON 02.12.2019 Universities 2276. SHRI COSME FRANCISCO CAITANO SARDINHA: Will the Minister of HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT be pleased to state: (a) whether any University in our country figures in the list of good universities listed by the international agencies; (b) if so, the details thereof; and (c) if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER MINISTER OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT (SHRI RAMESH POKHRIYAL ‘NISHANK’) (a) & (b): Yes, Sir. As per Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings-2020 and Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) World University Ranking-2020, 36 and 24 Indian Universities / Institutions respectively figure in the top 1000 World University Rankings. The details of these Institutions / Universities are at Annexure-I. (c): In view of the above, does not arise. Annexure-I ANNEXURE REFERRED IN REPLY TO PART (a) AND (b) OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2276 TO BE ANSWERED ON 02.12.2019 ASKED BY HONBLE MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT SHRI COSME FRANCISCO CAITANO SARDINHA REGARDING UNIVERSITIES List of Institutions / Universities found placed in top 1000 of world reputed ranking Agencies Agency THE World University Ranking QS World University Ranking-2020 Sl No. 2020 (Position) (Position) i. IISc, Bangalore – 301-350 IIT, Bombay - 152 ii. IIT, Ropar – 301-350 IIT, Delhi – 182 iii. IIT, Indore – 351-400 IISc, Bangalore - 184 iv. IIT, Bombay – 401-500 IIT, Madras – 271 v. IIT, Delhi - 401-500 IIT, Kharagpur – 281 vi. IIT, Kharagpur – 401-500 IIT, Kanpur - 291 vii. Institute of Chemical Technology, IIT, Roorkee – 383 Mumabi – 501-600 viii. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

The Pneumatic Experiences of the Indian Neocharismatics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE PNEUMATIC EXPERIENCES OF THE INDIAN NEOCHARISMATICS By JOY T. SAMUEL A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2018 i University of Birmingham Research e-thesis repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and /or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any success or legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. i The Abstract of the Thesis This thesis elucidates the Spirit practices of Neocharismatic movements in India. Ever since the appearance of Charismatic movements, the Spirit theology has developed as a distinct kind of popular theology. The Neocharismatic movement in India developed within the last twenty years recapitulates Pentecostal nature spirituality with contextual applications. Pentecostalism has broadened itself accommodating all churches as widely diverse as healing emphasized, prosperity oriented free independent churches. Therefore, this study aims to analyse the Neocharismatic churches in Kerala, India; its relationship to Indian Pentecostalism and compares the Sprit practices. It is argued that the pneumatology practiced by the Neocharismatics in Kerala, is closely connected to the spirituality experienced by the Indian Pentecostals. -

Abstract Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Anti

ABSTRACT KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAYA, ANTI-IMPERIALIST AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 1939-41 by Julie Laut Barbieri This paper utilizes biographies, correspondence, and newspapers to document and analyze the Indian socialist and women’s rights activist Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya’s (1903-1986) June 1939-November 1941 world tour. Kamaladevi’s radical stance on the nationalist cause, birth control, and women’s rights led Gandhi to block her ascension within the Indian National Congress leadership, partially contributing to her decision to leave in 1939. In Europe to attend several international women’s conferences, Kamaladevi then spent eighteen months in the U.S. visiting luminaries such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Margaret Sanger, lecturing on politics in India, and observing numerous social reform programs. This paper argues that Kamaladevi’s experience within Congress throughout the 1930s demonstrates the importance of gender in Indian nationalist politics; that her critique of Western “international” women’s organizations must be acknowledged as a precursor to the politics of modern third world feminism; and finally, Kamaladevi is one of the twentieth century’s truly global historical agents. KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAYA, ANTI-IMPERIALIST AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 1939-41 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History By Julie Laut Barbieri Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 Advisor____________________________ (Judith P. Zinsser) Reader_____________________________ (Mary E. Frederickson) Reader_____________________________ (David M. Fahey) © Julie Laut Barbieri 2008 For Julian and Celia who inspire me to live a purposeful life. Acknowledgements March 2003 was an eventful month. While my husband was in Seattle at a monthly graduate school session, I discovered I was pregnant with my second child. -

Open Chindhade Final Dissertation

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of German PRESENTING AND COMPARING EARLY MARATHI AND GERMAN WOMEN’S FEMINIST WRITINGS (1866-1933): SOME FINDINGS A Dissertation in German by Tejashri Chindhade © 2010 Tejashri Chindhade Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 The dissertation of Tejashri Chindhade was reviewed and approved* by the following: Daniel Purdy Associate Professor of German Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Thomas.O. Beebee Professor of Comparative Literature and German Reiko Tachibana Associate Professor of Japanese and Comparative Literature Kumkum Chatterjee Associate Professor of South Asia Studies B. Richard Page Associate Professor of German and Linguistics Head of the Department of German *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract In this dissertation I present the feminist writings of four Marathi women writers/ activists Savitribai Phule’s “ Prose and Poetry”, Pandita Ramabai’s” The High Caste Hindu Woman”, Tarabai Shinde’s “Stri Purush Tualna”( A comparison between women and men) and Malatibai Bedekar’s “Kalyanche Nihshwas”( “The Sighs of the buds”) from the colonial period (1887-1933) and compare them with the feminist writings of four German feminists: Adelheid Popp’s “Jugend einer Arbeiterin”(Autobiography of a Working Woman), Louise Otto Peters’s “Das Recht der Frauen auf Erwerb”(The Right of women to earn a living..), Hedwig Dohm’s “Der Frauen Natur und Recht” (“Women’s Nature and Privilege”) and Irmgard Keun’s “Gilgi: Eine Von Uns”(Gilgi:one of us) (1886-1931), respectively. This will be done from the point of view of deconstructing stereotypical representations of Indian women as they appear in westocentric practices. -

Unit 12 Resistance and Protest* Structure 12.0 Objectives 12.1 Introduction 12.2 Caste

Unit 12 Resistance and Protest* Structure 12.0 Objectives 12.1 Introduction 12.2 Caste: Characteristic of Indian Society 12.2.1 Caste and the Ideology of Hierarchy 12.3 Early Critiques and Struggles 12.3.1 Feminist Crusade against the Patriarchy: Rambai, Tarabai and Beyond 12.3.2 Contributions of Phule and Ambedkar: Dalits' Fight against caste Oppression 12.4. The New Social Movements and the Caste Question 12.5 Lets Sum Up 12.6 Key Words 12.7 Further Readings 12.8 Specimen Answers 12.0 Objectives After reading this unit, you should be able to: elaborate that caste practices and rituals have met with strong resistance and protest; understand that culture of resistance and protest at the intellectual and religious level ; Discuss subaltern perspectives on caste. * * written by Kanika Kakar, Delhi University 1 12.1 Introduction There is a common perception regarding Hinduism subscribed by its adherents that relates essentially to its pluralistic content and tolerant tradition. This portrayal of Hinduism as a template for tolerance glosses over its most divisive element — caste and silences the struggles and protests launched by those outside the Hindu framework. To regard India in the context of single-system of Hindu conception of social order is therefore inadequate. The resistance and protests launched by non-Hindu and non-Brahmanical forces makes it necessary to relate theory of social structure with the idea of change. They bring into questioning the functional presuppositions of social system/caste system (Singh, Yogendra 1986:66) and the dominant idea that India is a nation of Hindus. -

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination by Purvi Mehta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Chair Professor Pamela Ballinger Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Mrinalini Sinha Dedication For my sister, Prapti Mehta ii Acknowledgements I thank the dalit activists that generously shared their work with me. These activists – including those at the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights, Navsarjan Trust, and the National Federation of Dalit Women – gave time and energy to support me and my research in India. Thank you. The research for this dissertation was conducting with funding from Rackham Graduate School, the Eisenberg Center for Historical Studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the Center for Comparative and International Studies, and the Nonprofit and Public Management Center. I thank these institutions for their support. I thank my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan for their years of guidance. My adviser, Farina Mir, supported every step of the process leading up to and including this dissertation. I thank her for her years of dedication and mentorship. Pamela Ballinger, David Cohen, Fernando Coronil, Matthew Hull, and Mrinalini Sinha posed challenging questions, offered analytical and conceptual clarity, and encouraged me to find my voice. I thank them for their intellectual generosity and commitment to me and my project. Diana Denney, Kathleen King, and Lorna Altstetter helped me navigate through graduate training. -

Savitribai Phule: Empowers Today's Women

AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 Savitribai Phule: Empowers today’s women Dr. BeenaIndrani Former Guest Faculty, Department of Education, University of Allahabad, Prayagraj, U.P. (India) Email Id: [email protected] ABSTRACT SavitribaiPhule may not be as famous as Mahatma Gandhi or Tagore or Vivekanand. But her impact on the liberation of the Indian woman has been no less significant. One of the earliest crusaders of education for girls, and dignity for the most vulnerable sections of society- dalit, women and widows. She broke all the traditional shackles and stereotypes of 19 th century India to boost a new age of thinking in British colonised India. She can be legitimately called as the mother of Indian Feminism. She was the first female teacher of the first women's school in India. She is India's first modern feminist and well known social reformer who along with her husband JyotiraoPhule. Both had played a vital role in raising the human rights in India during the British Rule. At a time, when India was plagued with women’s outraged modesty. She acted as a Messiah for all those who were living a life of slavery. During a time when women were mere objects, she ignited a spark that led to equality in education which was impossible before. SavitribaiPhule is a name that everyone needs to know and understand their thoughts today. Her ideas are relevant and useful even today, despite the British era. Here in this paper, an attempt has been made to explain why she is called the mother of modern girls' education, how her thoughts can play their role in the women empowerment? How she is an educational pragmatist? and in the end it is told how her initiatives have influenced the modern education system even today. -

Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1772 — 1833)

UNIT – II SOCIAL THINKERS RAJA RAM MOHAN ROY (1772 — 1833) Introduction: Raja Ram Mohan Roy was a great socio-religious reformer. He was born in a Brahmin family on 10th May, 1772 at Radhanagar, in Hoogly district of Bengal (now West Bengal). Ramakanto Roy was his father. His mother’s name was Tarini. He was one of the key personalities of “Bengal Renaissance”. He is known as the “Father of Indian Renaissance”. He re- introduced the Vedic philosophies, particularly the Vedanta from the ancient Hindu texts of Upanishads. He made a successful attempt to modernize the Indian society. Life Raja Ram Mohan Roy was born on 22 May 1772 in an orthodox Brahman family at Radhanagar in Bengal. Ram Mohan Roy’s early education included the study of Persian and Arabic at Patna where he read the Quran, the works of Sufi mystic poets and the Arabic translation of the works of Plato and Aristotle. In Benaras, he studied Sanskrit and read Vedas and Upnishads. Returning to his village, at the age of sixteen, he wrote a rational critique of Hindu idol worship. From 1803 to 1814, he worked for East India Company as the personal diwan first of Woodforde and then of Digby. In 1814, he resigned from his job and moved to Calcutta in order to devote his life to religious, social and political reforms. In November 1930, he sailed for England to be present there to counteract the possible nullification of the Act banning Sati. Ram Mohan Roy was given the title of ‘Raja’ by the titular Mughal Emperor of Delhi, Akbar II whose grievances the former was to present 1/5 before the British king. -

Caste & Untouchability

Paggi fr. Luigi s.x. * * * * * * * * Caste & untouchability Pro Manuscripto Title: Caste & untouchability. A study-research paper in the Indian Subcontinent Authored by: Paggi fr. Luigi sx Edited by: Jo Ellen Fuller- 2002 Photographs by: Angelo fr. Costalonga sx Printed by: “Museo d’Arte Cinese ed Etnografico di Parma” - 2005 © 2005 Museo d’Arte Cinese ed Etnografico © Paggi fr. Luigi sx A few years ago, my confreres (Xaverian Missionaries working in Bangladesh) requested that I conduct a four-day course on caste and untouchability. Probably, I benefited as much from teaching the course as my student-confreres did since the process helped me crystallize my ideas about Hinduism and the ramifications of certain aspects of this religion upon the cultures of the subcontinent. From time to time, I am invited to different places to deliver lectures on these two topics. I usually accept these invitations because I am convinced that those who would like to do something to change the miserable lot of so many poor people living in the Indian Subcontinent must be knowledgeable about the caste system and untouchability. People need to be aware of the negative effect and the impact of these two social evils regarding the abject misery and poverty of those who are at the bot- tom of the greater society. It seems that people living in the Indian Subcontinent , no matter which reli- gion they belong to, are still affected (consciously or unconsciously) by these as- pects of Hinduism that have seeped into other religions as well. In order to prepare myself for the task of lecturing (on caste and untoucha- bility), I read and studied many books, magazines and articles on these two evil institutions of Hinduism, which have affected the social life of most of the people living in the Indian Subcontinent. -

Syllabus for MA Online Entrance Examination 2021

Savitribai Phule Pune University Syllabus for the MA (Political Science) Online Entrance Examination UNIT 1 INDIAN GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS Topic 1: Background and Salient Features of the Indian Constitution a) Formation of the Constituent Assembly b) Philosophy of the Preamble to the Indian Constitution c) Major Features: Parliamentary Democracy, Federalism, Independent Judiciary, Social Justice and Social Transformation Topic 2: Fundamental Rights, Duties and the Directive Principles of State Policy a) Nature of Fundamental Rights –Major Fundamental Rights-Right to Equality, Right to Liberty, Right to Freedom of Religion, Cultural and Educational Rights b) Importance of Fundamental Duties c) Nature and Significance of Directive Principles of State Policy Topic 3: Federalism a) Salient Features of Indian Federalism b) Centre –State Relations c) Issues of Conflict-Water Issues, Border Issues and Sharing of Resources Topic 4: Structure of the Union Government – Legislature, Executive, Judiciary a) Union Legislature – Structure, Powers and Role b) Union Executive – President, Prime Minister and the Cabinet: Role and Functions c) Judiciary – Nature of the Judiciary, Supreme Court: Powers and Functions Topic 5: Structure of State Government – Legislature, Executive, Judiciary a) State Legislature – Structure, Powers and Role b) State Executive – Governor, Chief Minister and the Cabinet: Role and Functions c) Judiciary- Nature of the Judiciary, High Court: Powers and Functions Topic 6: Party System and Elections a) Nature and Changing Pattern