Idea of Emancipation and Discourse on Caste in Colonial Western India (Maharashtra)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo Ghosh

UNIT 6 HINDUISM : SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND SRI AUROBINDO GHOSH Structure 6.2 Renaissance of Hi~~duis~iiand the Role of Sri Raniakrishna Mission 0.3 Swami ViveItananda's Philosopliy of Neo-Vedanta 6.4 Swami Vivckanalida on Nationalism 6.4.1 S\varni Vivcknnnnda on Dcrnocracy 6.4.2 Swami Vivckanar~daon Social Changc 6.5 Transition of Hinduism: Frolii Vivekananda to Sri Aurobindo 6.5. Sri Aurobindo on Renaissance of Hinduism 6.2 Sri Aurol>i~ldoon Evil EffLrcls of British Rulc 6.6 S1.i Aurobindo's Critique of Political Moderates in India 6.6.1 Sri Aurobilido on the Essencc of Politics 6.6.2 SI-iAurobindo oil Nationalism 0.6.3 Sri Aurobindo on Passivc Resistance 6.6.4 Thcory of Passive Resistance 6.6.5 Mcthods of Passive Rcsistancc 6.7 Sri Aurobindo 011 the Indian Theory of State 6.7.1 .J'olitical ldcas of Sri Aurobindo - A Critical Study 6.8 Summary 1 h 'i 6.9 Exercises j i 6.1 INTRODUCTION In 19"' celitury, India camc under the British rule. Due to the spread of moder~ieducation and growing public activities, there developed social awakening in India. The religion of Hindus wns very harshly criticized by the Christian n?issionaries and the British historians but at ~hcsanie timc, researches carried out by the Orientalist scholars revealcd to the world, lhc glorioi~s'tiaadition of the Hindu religion. The Hindus responded to this by initiating reforms in thcir religion and by esfablishing new pub'lie associations to spread their ideas of refor111 and social development anlong the people. -

1. Details of Module and Its Structure 2. Development Team

1. Details of Module and its Structure Module Detail Subject Name Sociology Paper Name Sociology of India Module Name/Title Non Brahmin Approach: Mahatma Phule Pre-requisites Basic thoughts about caste system in India, low caste protest in nineteenth century western India, religion and society under early British rule in India. Objectives To introduce the students to the non-brahmanical approach. To familiarize students with the contribution of Mahatma Phule To acquaint the students with the perspectives of Mahatma Jyotirao Phule. Keywords Brahmanism, caste, peasant oppression, non brahmanical approach, varna, women oppression, dichotomy, caste conflict. 2. Development Team Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Sujata Patel Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator Anurekha Chari Wagh Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Savitribai Phule Pune Univiersity Content Writer/Author Deepti Gokhale Oak Assistant Lecturer, St. Bishop’s Junior (CW) College, Camp, Pune Content Reviewer (CR) Anurekha Chari Wagh Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Savitribai Phule Pune Univiersity Language Editor (LE) Erika Mascarenas Senior English Teacher, Kendriya Vidyalaya, Pune Table of Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Section One: Understanding Nineteenth Century: Mahatma Phule, 3. Section Two: Dharma and Caste: Mahatma Phule, 4. Section Three: Women and Education: Philosophy of Mahatma Phule, 5. Section Four: Agriculture and Peasants: Mahatma Phule, 6. Section Five: Satyashodhak Samaj and Non-Brahmin -

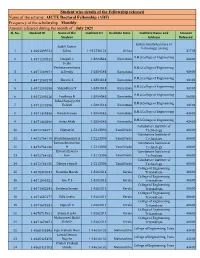

Student Wise Details of the Fellowship Released Name of the Scheme

Student wise details of the Fellowship released Name of the scheme: AICTE Doctoral Fellowship (ADF) Frequency of the scholarship –Monthly Amount released during the month of : July 2021 Sl. No. Student ID Name of the Institute ID Institute State Institute Name and Amount Student Address Released Indira Gandhi Institute of Sushil Kumar Technology, Sarang 1 1-4064399722 Sahoo 1-412736121 Orissa 31703 B.M.S.College of Engineering 2 1-4071237529 Deepak C 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Perla Venkatasreenivasu B.M.S.College of Engineering 3 1-4071249071 la Reddy 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 4 1-4071249170 Shruthi S 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 5 1-4071249196 Vidyadhara V 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 6 1-4071249216 Pruthvija B 1-5884543 Karnataka 86800 Tulasi Naga Jyothi B.M.S.College of Engineering 7 1-4071249296 Kolanti 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 8 1-4071448346 Manali Raman 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 9 1-4071448396 Anisa Aftab 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Coimbatore Institute of 10 1-4072764071 Vijayan M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 11 1-4072764119 Sivasubramani P A 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Ramasubramanian Coimbatore Institute of 12 1-4072764136 M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Eswara Eswara Coimbatore Institute of 13 1-4072764153 Rao 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 14 1-4072764158 Dhivya Priya N 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 -

Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of Higher Education

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2276 TO BE ANSWERED ON 02.12.2019 Universities 2276. SHRI COSME FRANCISCO CAITANO SARDINHA: Will the Minister of HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT be pleased to state: (a) whether any University in our country figures in the list of good universities listed by the international agencies; (b) if so, the details thereof; and (c) if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER MINISTER OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT (SHRI RAMESH POKHRIYAL ‘NISHANK’) (a) & (b): Yes, Sir. As per Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings-2020 and Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) World University Ranking-2020, 36 and 24 Indian Universities / Institutions respectively figure in the top 1000 World University Rankings. The details of these Institutions / Universities are at Annexure-I. (c): In view of the above, does not arise. Annexure-I ANNEXURE REFERRED IN REPLY TO PART (a) AND (b) OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2276 TO BE ANSWERED ON 02.12.2019 ASKED BY HONBLE MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT SHRI COSME FRANCISCO CAITANO SARDINHA REGARDING UNIVERSITIES List of Institutions / Universities found placed in top 1000 of world reputed ranking Agencies Agency THE World University Ranking QS World University Ranking-2020 Sl No. 2020 (Position) (Position) i. IISc, Bangalore – 301-350 IIT, Bombay - 152 ii. IIT, Ropar – 301-350 IIT, Delhi – 182 iii. IIT, Indore – 351-400 IISc, Bangalore - 184 iv. IIT, Bombay – 401-500 IIT, Madras – 271 v. IIT, Delhi - 401-500 IIT, Kharagpur – 281 vi. IIT, Kharagpur – 401-500 IIT, Kanpur - 291 vii. Institute of Chemical Technology, IIT, Roorkee – 383 Mumabi – 501-600 viii. -

Question Bank Mcqs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra

Question Bank MCQs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra 1. Who founded the SNDT University for women in 1916? a) M.G.Ranade b) Dhondo Keshav Karve c) Gopal Krishna Gokhale d) Bal Gangadhar Tilak 2. Who was associated with the Satyashodhak Samaj? a) Sri Narayan Guru b) Jyotirao Phule c) Dr. B. R. Ambedkar d) E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker 3. When was the Indian National Congress established? a) 1875 b) 1885 c) 1905 d) 1947 4. Which Marathi newspaper was published by Bal Gangadhar Tilak a) Kesari b) Poona Vaibhav c) Sakal d) Darpan 5. Which day is celebrated as the Maharashtra Day? a) 12th January b) 14th April c) 1st May d) 2nd October 6. Under whose leadership Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti was founded? a) Keshavrao Jedhe b) S. A. Sange c) Uddhavrao Patil d) Narayan Ganesh Gore 7. When did the Bilingual Bombay State come into existence? a) 1960 b) 1962 c) 1956 d) 1947 8. Which one of the following city comes under Vidarbha region? a) Nagpur b) Poona c) Aurangabad d) Raigad 9. Till 1948 Marathwada region was part of which of the following? a) Central Province and Berar b) Bombay State c) Hyderabad State d) Junagad 10. Dandekar Committee dealt with which of the following issues? a) Maharashtra’s Educational policy b) The problem of imbalance in development between different regions of Maharashtra c) Trade and commerce policy of Maharashtra d) Agricultural policy 11. Which one of the following is known as the financial capital of India? a) Pune b) Mumbai c) Nagpur d) Aurangabad 12. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

Lokmanya Tilak's Editorials for Mass Education

International Journal of Disaster Recovery and Business Continuity Vol.11, No. 1 (2020), pp. 572-590 LOKMANYA TILAK’S EDITORIALS FOR MASS EDUCATION Dr. Deepak J. Tilak Vice Chancellor, Tilak Maharasthra Vidyapeeth, Pune Dr. Geetali D. Tilak Professor, Department of Mass Communication Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune Abstract Lokmanya B.G. Tilak wanted to educate people about drain theory, inequality, injustice, poverty and colonial dual policy for the common man. He realized that common man should know all these facts and should be aware of the injustice to them and to know the parademic situation around them which will create awareness for his birth right – Swaraj. Lokmanya Tilak’s Editorials in Kesari was a fight against the British Government and created unrest against British colonial policies. This research paper is confined to 1890 to 1920 and media writing of the great patriot Lokmanya B.G. Tilak who wrote various articles in his newspaper “Kesari” to educate the masses about need of Swarajya and means of development of India. Lokmanya Tilak was a great orator, he used his lectures as a storytelling tool to educate the masses about need of Swarajya and means of development of India. Lokmanya Tilak had the strength to influentially express the subject matter. Thoughtful topic, proper words and pragmatic examples were the soul of his lectures. Lokmanya Tilak had very powerful skills to analyze the minute and enlighten very minute details of any subject, which always reflected in his lectures. Keywords: Lokmanya Tilak, Lokmanya Tilak’s editorials, articles, Kesari, Media, Education, British Government Introduction: Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak was multi-faceted personality in the 19th century in the freedom struggle also known as a spokesman of Swarajya, i.e. -

1 Pleistocene Climatic Changes in Western India

Abstract submitted for Mini Workshop “Future of the Past” to held at Gateway Hotel, Manglore, November 21 to 26, 2011 Pleistocene Climatic Changes in Western India: A Geoarchaeological Approach S.N. Rajaguru, Sushama G. Deo and Sheila Mishra Deccan College, Pune Recently Dhavalikar in his A. Ghosh memorial lecture titled “Indian Archaeology in the 21st Century” delivered on 25th September 2011, in New Delhi, strongly emphasized the need of understanding past cultural changes in terms of palaeoenvironment. He has suggested that growth and decay of protohistoric and historic cultures in India have been largely influenced by changes in the intensity of monsoonal rainfall during the Holocene, approximately last 10,000 years. In the last 25 years considerable new scientific data have been generated for the Holocene climatic changes in India (Singhvi and Kale 2009). It is observed that the early Holocene (~ 10 ka years to 4 ka years) was significantly wetter than the late Holocene (< 4 ka years). These changes in summer rainfall of India have been mainly due to global climatic factors. In the present communication we have attempted to understand prehistoric cultural changes against the background of climatic changes of the Pleistocene, approximately covering time span from about 2 Ma years BP to about 10 ka BP. Recently Sanyal and Sinha (2010) and Singhvi et al (2011-12) have attempted reconstruction of palaeomonsoon in Indian subcontinent by using data generated through multidisciplinary studies of marine cores, continental- fluvial, fluvio- lacustral, aeolian, glacial and littoral deposits- preserved in different parts of India. However, there is no input of prehistoric cultural changes in these publications. -

The Pneumatic Experiences of the Indian Neocharismatics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE PNEUMATIC EXPERIENCES OF THE INDIAN NEOCHARISMATICS By JOY T. SAMUEL A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2018 i University of Birmingham Research e-thesis repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and /or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any success or legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. i The Abstract of the Thesis This thesis elucidates the Spirit practices of Neocharismatic movements in India. Ever since the appearance of Charismatic movements, the Spirit theology has developed as a distinct kind of popular theology. The Neocharismatic movement in India developed within the last twenty years recapitulates Pentecostal nature spirituality with contextual applications. Pentecostalism has broadened itself accommodating all churches as widely diverse as healing emphasized, prosperity oriented free independent churches. Therefore, this study aims to analyse the Neocharismatic churches in Kerala, India; its relationship to Indian Pentecostalism and compares the Sprit practices. It is argued that the pneumatology practiced by the Neocharismatics in Kerala, is closely connected to the spirituality experienced by the Indian Pentecostals. -

Abstract Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Anti

ABSTRACT KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAYA, ANTI-IMPERIALIST AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 1939-41 by Julie Laut Barbieri This paper utilizes biographies, correspondence, and newspapers to document and analyze the Indian socialist and women’s rights activist Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya’s (1903-1986) June 1939-November 1941 world tour. Kamaladevi’s radical stance on the nationalist cause, birth control, and women’s rights led Gandhi to block her ascension within the Indian National Congress leadership, partially contributing to her decision to leave in 1939. In Europe to attend several international women’s conferences, Kamaladevi then spent eighteen months in the U.S. visiting luminaries such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Margaret Sanger, lecturing on politics in India, and observing numerous social reform programs. This paper argues that Kamaladevi’s experience within Congress throughout the 1930s demonstrates the importance of gender in Indian nationalist politics; that her critique of Western “international” women’s organizations must be acknowledged as a precursor to the politics of modern third world feminism; and finally, Kamaladevi is one of the twentieth century’s truly global historical agents. KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAYA, ANTI-IMPERIALIST AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 1939-41 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History By Julie Laut Barbieri Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 Advisor____________________________ (Judith P. Zinsser) Reader_____________________________ (Mary E. Frederickson) Reader_____________________________ (David M. Fahey) © Julie Laut Barbieri 2008 For Julian and Celia who inspire me to live a purposeful life. Acknowledgements March 2003 was an eventful month. While my husband was in Seattle at a monthly graduate school session, I discovered I was pregnant with my second child. -

Morphotectonic of Sabarmati-Cambay Basin, Gujarat, Western India V.21, No.5, Pp: 371-383

J. Ind. Geophys. Union ( September 2017 ) Morphotectonic of Sabarmati-Cambay basin, Gujarat, Western India v.21, no.5, pp: 371-383 Morphotectonic of Sabarmati-Cambay basin, Gujarat, Western India Vasu Pancholi*1, Girish Ch Kothyari1, Siddharth Prizomwala1, Prabhin Sukumaran2, R. D. Shah3, N. Y. Bhatt3 Mukesh Chauhan1 and Raj Sunil Kandregula1 1Institute of Seismological Research, Raisan Gandhinagar, Gujarat 2Charotar University of Science and Technology (CHARUSAT), Vallabh Vidhyanagar, Gujarat 3Department of Geology, MG. Science College Ahmedabad, Gujarat *Corresponding Author: [email protected] ABSTracT The study area is a part of the peri-cratonic Sabarmati-Cambay rift basin of western Peninsular India, which has experienced in the historical past four earthquakes of about six magnitude located at Mt. Abu, Paliyad, Tarapur and Gogha. Earthquakes occurred not only along the two major rift boundary faults but also on the smaller longitudinal as well as transverse faults. Active tectonics is the major controlling factor of landform development, and it has been significantly affected by the fluvial system in the Sabarmati- Cambay basin. Using the valley morphology and longitudinal river profile of the Sabarmati River and adjoining trunk streams, the study area is divided into two broad tectono-morphic zones, namely Zone-1 and Zone-2. We computed stream length gradient index (SL) and steepness index (Ks) to validate these zones. The study suggests that the above mentioned structures exert significant influence on the evolution of fluvial landforms, thus suggesting tectonically active nature of the terrain. Based on integration of the morphometry and geomorphic expressions of tectonic instability, it is suggested that Zone-2 is tectonically more active as compared to Zone-1. -

Peasants, Famine and the State in Colonial Western India This Page Intentionally Left Blank Peasants, Famine and the State in Colonial Western India

Peasants, Famine and the State in Colonial Western India This page intentionally left blank Peasants, Famine and the State in Colonial Western India David Hall-Matthews © David Hall-Matthews 2005 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2005 978-1-4039-4902-8 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 2005 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-52538-6 ISBN 978-0-230-51051-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230510517 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources.