Kristiina Korhonen with Erja Kettunen & Mervi Lipponen DEVELOPMENT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NÄIN KOIMME KANSANRINTAMAN Puoluepoliitikkojen Muistelmateosten Kerronta Vuoden 1966 Hallitusratkaisuun Johtaneista Tekijöistä

Lauri Heikkilä NÄIN KOIMME KANSANRINTAMAN Puoluepoliitikkojen muistelmateosten kerronta vuoden 1966 hallitusratkaisuun johtaneista tekijöistä Yhteiskuntatieteiden tiedekunta Historian pro gradu-tutkielma Marraskuu 2019 TIIVISTELMÄ Heikkilä, Lauri: Näin koimme kansanrintaman – Puoluepoliitikko!en muistelmateosten kerronta vuoden 1966 hallitusratkaisuun johtaneista teki!öistä pro gradu-tutkielma %ampereen yliopisto Historian tutkinto-ohjelma Marraskuu 2019 Tässä pro gradu-tutkielmassa tutkitaan poliitikkojen muistelmia !a niiden kautta muodostuvaa kuvaa vuoden 1966 hallitusratkaisuun johtaneista teki!öistä' ainopiste on puolueissa toimineissa poliitikoissa, !oilla on takanaan merkittä"ä ura hallituksen tai eduskunnan tehtävissä tai puolueiden !ohtopaikoilla' Muistelmien perusteella luotua kuvaa tarkastellaan muistelma-käsitteen kautta !a poliittisia- sekä valtadiskursse!a kriittisen diskurssianal&&sin periaatteita noudattaen. Muistelmissa tar!ottu poliittinen selit&s on usein monis&isempi !a itsere(lektoivampi kuin a!anjohtaiset poliittiset selit&kset, mutta poliittinen painolasti !a poliittinen selit&starve kuultaa muistelmistakin läpi' oliitikot !atkavat !o aktiiviurallaan alkanutta diskurssia p&rkien varmistamaan poliittisen perintönsä säil&misen, mutta he tavoittele"at m&$s tulkitun historian omista!uutta kokemistaan asioista, ettei heidän tulkintansa !äisi unohduksiin !a etteivät muut tulkinnat ota sitä tilaa, jonka koki!at koke"at kuuluvan heille itselleen. %arkasteltavat muistelmateokset ovat )* :n +a(ael aasion Kun aika on kypsä -

The Nordic Countries and the European Security and Defence Policy

bailes_hb.qxd 21/3/06 2:14 pm Page 1 Alyson J. K. Bailes (United Kingdom) is A special feature of Europe’s Nordic region the Director of SIPRI. She has served in the is that only one of its states has joined both British Diplomatic Service, most recently as the European Union and NATO. Nordic British Ambassador to Finland. She spent countries also share a certain distrust of several periods on detachment outside the B Recent and forthcoming SIPRI books from Oxford University Press A approaches to security that rely too much service, including two academic sabbaticals, A N on force or that may disrupt the logic and I a two-year period with the British Ministry of D SIPRI Yearbook 2005: L liberties of civil society. Impacting on this Defence, and assignments to the European E Armaments, Disarmament and International Security S environment, the EU’s decision in 1999 to S Union and the Western European Union. U THE NORDIC develop its own military capacities for crisis , She has published extensively in international N Budgeting for the Military Sector in Africa: H management—taken together with other journals on politico-military affairs, European D The Processes and Mechanisms of Control E integration and Central European affairs as E ongoing shifts in Western security agendas Edited by Wuyi Omitoogun and Eboe Hutchful R L and in USA–Europe relations—has created well as on Chinese foreign policy. Her most O I COUNTRIES AND U complex challenges for Nordic policy recent SIPRI publication is The European Europe and Iran: Perspectives on Non-proliferation L S Security Strategy: An Evolutionary History, Edited by Shannon N. -

Speaker Profiles – Global Forum 2006 – ITEMS International 2

The present document has been finalized on 30 November 2006. The bios not sent in time to the editorial staff are missing. Speaker Profiles – Global Forum 2006 – ITEMS International 2 DONALD ABELSON, FELLOW, ANNENBERG CENTER FOR COMMUNICATIONS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, USA Donald Abelson has been president of Sudbury International since June 2006; he is also a non-resident fellow at the Annenberg Center for Communications at the University of Southern California. Previously he was Chief of the International Bureau at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) (from 1999 to 2006). In this capacity, he managed a staff of 155 professionals who coordinated the FCC’s international activities, including its approval of international telecommunication services (including the licensing of all satellite facilities). Mr. Abelson directed the FCC’s provision of technical advice to developing countries on regulatory matters, as well as to the U.S. Executive Branch regarding bilateral “free trade agreements” (FTAs) and the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) (including, the World Radiocommunications Conferences) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Mr. Abelson also was a member of the FCC’s executive team that coordinated spectrum policy matters, with a particular interest in satellite and terrestrial services and networks. Abelson came to the Commission with extensive experience in international communications regulatory issues. In 1998 and 1999, he served as Assistant U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) for Industry and Communications, during which time he led USTR’s effort to facilitate global electronic commerce over the Internet. Prior to that assignment, as USTR’s Chief Negotiator for Communications and Information, Abelson was the lead U.S. -

Strategic Low Profile and Bridge-Building: Finnish Foreign Policy During Mauno Koivisto's Presidency

Strategic Low Profile and Bridge-Building: Finnish Foreign Policy during Mauno Koivisto's Presidency Michiko Takagi Graduate Student of Nagoya University 1. Introduction This paper focuses on Finnish foreign policy conducted by Mauno Koivisto, who was the President of Finland between 1981 and 1994. In the beginning of 80s when he took office as president, relationship between superpowers was aggravated and the international tension flared up again, just called as “New Cold War”. However, after the change of political leader of the Soviet Union in 1985, the East and West tension relieved drastically, which eventually led to the end of the Cold War and reunification of Germany. Furthermore, a number of remarkable transformations in Europe began to occur, such as democratization in East European states, collapse of the Soviet Union and acceleration of European economic and political integration. During the Cold War, Finland maintained its independence by implementing “good-neighboring policies” towards the Soviet Union based on YYA treaty, bilateral military treaty with the Soviet Union (1948)1), on the other hand, in spite of this, by pursuing policy of neutrality. In the period of “Détente” of 70s, Urho Kekkonen, the President of Finland at the time, carried out policy of active neutrality, which culminated in success of “Helsinki Process” in 1975 and this Finnish policy of bridge-building between East and West increased its presence in the international community. However, Finnish position and presence as a neutral country fluctuated during the “New Cold War” and the following end of the Cold War. This 1) The Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance (Sopimus ystävyydestä, yhteistoiminnasta ja keskinäisestä avunannosta). -

Seppo Hentilä.Indb

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto President Urho Kekkonen of Finland and the KGB K IMMO RENTOLA A major post-Cold War history debate in Finland has been over the role of President Urho Kekkonen and his relations with the Soviet Union, in particular with the Soviet foreign intelligence. No surprise to anybody, variance of interpretations has been wide, fuelled by scarcity of sources on the most sensitive aspects, by the unavoidable ambiguity of an issue like the intelligence, and even by political leanings.1 As things stand now, even a preliminary assessment of available evidence – viewed from a distance – might prove useful. The Soviet Union regularly tried to build back-channel contacts and confi dential informal links with the Western powers. On the Soviet side, these contacts were usually conducted by intelligence offi cers, as were those to Robert Kennedy on the eve of the Cuban missile crisis,2 and to Chancellor Willy Brandt during his new German Ostpolitik.3 By far the 1 A good introduction to Finnish studies on Kekkonen in J. Lavery. ‘All of the President’s Historians: The Debate over Urho Kekkonen’, Scandinavian Studies 75 (2003: 3). See also his The History of Finland. Westport: Greenwood Press 2006, and the analysis of D. Kirby, A Concise History of Finland. Cambridge University Press 2006. 2 An account by G. Bolshakov, ‘The Hot Line’, in New Times (Moscow), 1989, nos. 4-6; C. Andrew, For the President’s Eyes Only: Secret Intelligence and American Presidency from Washington to Bush. -

From the Tito-Stalin Split to Yugoslavia's Finnish Connection: Neutralism Before Non-Alignment, 1948-1958

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FROM THE TITO-STALIN SPLIT TO YUGOSLAVIA'S FINNISH CONNECTION: NEUTRALISM BEFORE NON-ALIGNMENT, 1948-1958. Rinna Elina Kullaa, Doctor of Philosophy 2008 Directed By: Professor John R. Lampe Department of History After the Second World War the European continent stood divided between two clearly defined and competing systems of government, economic and social progress. Historians have repeatedly analyzed the formation of the Soviet bloc in the east, the subsequent superpower confrontation, and the resulting rise of Euro-Atlantic interconnection in the west. This dissertation provides a new view of how two borderlands steered clear of absorption into the Soviet bloc. It addresses the foreign relations of Yugoslavia and Finland with the Soviet Union and with each other between 1948 and 1958. Narrated here are their separate yet comparable and, to some extent, coordinated contests with the Soviet Union. Ending the presumed partnership with the Soviet Union, the Tito-Stalin split of 1948 launched Yugoslavia on a search for an alternative foreign policy, one that previously began before the split and helped to provoke it. After the split that search turned to avoiding violent conflict with the Soviet Union while creating alternative international partnerships to help the Communist state to survive in difficult postwar conditions. Finnish-Soviet relations between 1944 and 1948 showed the Yugoslav Foreign Ministry that in order to avoid invasion, it would have to demonstrate a commitment to minimizing security risks to the Soviet Union along its European political border and to not interfering in the Soviet domination of domestic politics elsewhere in Eastern Europe. -

Taxonomy of Minority Governments

Indiana Journal of Constitutional Design Volume 3 Article 1 10-17-2018 Taxonomy of Minority Governments Lisa La Fornara [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijcd Part of the Administrative Law Commons, American Politics Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, International Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Legislation Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, Rule of Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation La Fornara, Lisa (2018) "Taxonomy of Minority Governments," Indiana Journal of Constitutional Design: Vol. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijcd/vol3/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Constitutional Design by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Taxonomy of Minority Governments LISA LA FORNARA INTRODUCTION A minority government in its most basic form is a government in which the party holding the most parliamentary seats still has fewer than half the seats in parliament and therefore cannot pass legislation or advance policy without support from unaffiliated parties.1 Because seats in minority parliaments are more evenly distributed amongst multiple parties, opposition parties have greater opportunity to block legislation. A minority government must therefore negotiate with external parties and adjust its policies to garner the majority of votes required to advance its initiatives.2 This paper serves as a taxonomy of minority governments in recent history and proceeds in three parts. -

Speaker Profiles – Global Forum 2015 – ITEMS International 1

Speaker Profiles – Global Forum 2015 – ITEMS International 1 JØRGEN ABILD ANDERSEN, DIRECTOR GENERAL TELECOM (RTD.) CHAIRMAN OF OECD'S COMMITTEE ON DIGITAL ECONOMY POLICY, DENMARK Jørgen Abild Andersen is among the World’s most experienced experts within the ICT area. Mr Abild Andersen served as telecom regulator in Denmark from 1991 to 2012. Mr Abild Andersen gained a Masters of Law from the University of Copenhagen in 1975. He started his career as a civil servant in the Ministry of Public Works and for a three-year period he served as Private Secretary to the Minister. From 2003 to 2004 he was chairing the European Commission’s Radio Spectrum Policy Group. In 2005, Mr. Abild Andersen served as Chair for European Regulators Group (ERG). From 2006 to 2010 he was Denmark’s representative at the European Commission’s i2010 High Level Group. And he has furthermore been representing his country at the Digital Agenda High Level Group until April 2013. Since October 2009 he serves as Chair of OECD's Committee for Digital Economy Policy (CDEP) – until December 2013 named ICCP. In 2013 he was a member of ICANN’s Accountability and Transparency Review Team 2. In 2013 he founded Abild Andersen Consulting – a company offering strategic advice to ministers, regulators and telcos on the Digital Economy Policy. MIKE AHMADI, GLOBAL DIRECTOR OF CRITICAL SYSTEMS SECURITY, SYNOPSYS, INC, USA Mike Ahmadi is the Global Director of Critical Systems Security for Codenomicon Ltd. Mike is well known in the field of critical infrastructure security, including industrial control systems and health care systems. -

Audited Annual Report 2012 Nordea 1, SICAV Socie´Te´ D’Investissement A` Capital Variable A` Compartiments Multiples

Audited Annual Report 2012 Nordea 1, SICAV Socie´te´ d’Investissement a` Capital Variable a` compartiments multiples Investment Fund under Luxembourg Law 562, rue de Neudorf L-2220 Luxembourg Grand Duchy of Luxembourg R.C.S. number: Luxembourg B-31442 No subscriptions can be received on the basis of these fi nancial reports. Subscriptions are only valid if made on the basis of the current prospectus accompanied by the latest annual report and the most recent semi-annual report, if published thereafter. Table of Contents Report of the Board of Directors 2 Report of the Investment Manager 3 Report of the Réviseur d’Entreprises agréé 4 Statement of Net Assets as of 31/12/2012 6 Statement of Operations and Changes in Net Assets for the year ended 31/12/2012 16 Statement of Statistics as at 31/12/2012 34 Statement of Investments in Securities and Other Net Assets as of 31/12/2012 Nordea 1 - African Equity Fund 44 Nordea 1 - Brazilian Equity Fund 46 Nordea 1 - Climate and Environment Equity Fund 47 Nordea 1 - Danish Bond Fund 48 Nordea 1 - Danish Kroner Reserve 49 Nordea 1 - Danish Mortgage Bond Fund 50 Nordea 1 - Emerging Consumer Fund 51 Nordea 1 - Emerging Market Blend Bond Fund 52 Nordea 1 - Emerging Market Bond Fund 55 Nordea 1 - Emerging Market Corporate Bond Fund 59 Nordea 1 - Emerging Market Local Debt Fund 62 Nordea 1 - Emerging Markets Focus Equity Fund 64 Nordea 1 - Emerging Stars Equity Fund 66 Nordea 1 - Euro Bank Debt Fund 68 Nordea 1 - Euro Diversifi ed Corporate Bond Fund 69 Nordea 1 - European Alpha Fund 72 Nordea 1 - European -

Finland As a Knowledge Economy 2.0 Halme, Lindy, Piirainen, Salminen, and White the WORLD BANK

Finland as a Knowledge Economy 2.0 as a Knowledge Economy Finland Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Science, Technology, and Innovation Halme, Lindy, Piirainen, Salminen, and White White Salminen, and Piirainen, Lindy, Halme, Finland as a Knowledge Public Disclosure Authorized Economy 2.0 Lessons on Policies and Governance Kimmo Halme, Ilari Lindy, Kalle A. Piirainen, Vesa Salminen, and Justine White, Editors THE WORLD BANK Public Disclosure Authorized Finland as a Knowledge Economy 2.0 DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Science, Technology, and Innovation Finland as a Knowledge Economy 2.0 Lessons on Policies and Governance Kimmo Halme, Ilari Lindy, Kalle A. Piirainen, Vesa Salminen, and Justine White, Editors © 2014 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 17 16 15 14 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. -

Interim Report Q2 2011 11082011En

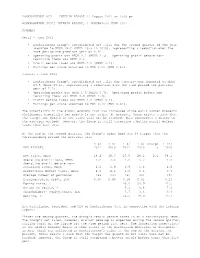

HONKARAKENNE OYJ INTERIM REPORT 11 August 2011 at 3:00 pm HONKARAKENNE OYJ’S INTERIM REPORT, 1 JANUARY–30 JUNE 2011 SUMMARY April - June 2011 • Honkarakenne Group’s consolidated net sales for the second quarter of the year amounted to MEUR 18.2 (MEUR 19.6 in 2010), representing a reduction over the same period the previous year of 6.9%. • Operating profit was MEUR 2.2 (MEUR 2.5). Operating profit before non- recurring items was MEUR 2.2. • Profit before taxes was MEUR 2.0 (MEUR 2.1). • Earnings per share amounted to EUR 0.30 (EUR 0.45). January - June 2011 • Honkarakenne Group’s consolidated net sales for January-June amounted to MEUR 27.5 (MEUR 28.1), representing a reduction over the same period the previous year of 2.2%. • Operating profit was MEUR 1.0 (MEUR 0.7). Operating profit before non- recurring items was MEUR 0.8 (MEUR 1.4). • Profit before taxes was MEUR 1.0 (MEUR 0.1). • Earnings per share amounted to EUR 0.18 (EUR 0.01). The uncertainty in the global economy that has increased since early summer presents challenges, especially for growth in net sales. At present, there exists a risk that the target for growth in net sales will not be reached. This represents a change to the previous outlook. However, the Group is still targeting a better result before taxes than last year. At the end of the second quarter, the Group’s order book was 3% larger than the corresponding period the previous year. 4-6/ 4-6/ 1-6/ 1-6/ Change 1-12/ KEY FIGURES 2011 2010 2011 2010 % 2010 Net sales, MEUR 18.2 19.6 27.5 28.1 2.2 58.1 Operating profit/loss, -

FINLANDS LINJE © Paavo Väyrynen Och Kustannusosakeyhtiö Paasilinna 2014

Paavo Väyrynen FINLANDS LINJE © Paavo Väyrynen och Kustannusosakeyhtiö Paasilinna 2014 Omslag: Laura Noponen ISBN 978-952-299-055-6 TILL LÄSAREN Under de senaste åren har jag sökt fördjupa mig i historien – såväl i händelser i det förgångna som i historieskrivning. Min första tidsresa hänger samman med Kemi stads åldringshem Niemi-Niemelä som vi köpte 1998. Jag skrev om det i boken Pohjanranta som utkom 2005. Verket har starka kopplingar till olika skeden i Norra bottens och hela Finlands utveckling. Min andra tidsresa gick till skeden knutna till min egen släkt. När min far fyllde 100 år i januari 2010 skrev jag en bok om honom – Eemeli Väyrysen vuosisata (Eemeli Väyrynens århundrade). Jag studerade min släkts rötter så långt dokumenten sträckte sig. Också detta arbete öppnade perspektiv på både min hembygds och hela landets historia. I min senaste bok Huonomminkin olisi voinut käydä (Det kunde också ha gått sämre) tillämpade jag en kontrafaktuell historieskrivningsmetod på mitt eget liv och min verksamhet. Jag funderade på hur det kunde ha gått om något avgörande gjorts på annat sätt. Denna granskningsmetod har sitt berättigande då beslut i praktiken ofta fattas som val mellan olika alternativ. Speciellt inom den ekonomiska historien kan 5 man i efterhand bedöma visheten i gjorda beslut. Inom politisk historia har kontrafaktuella metoder brukats i liten utsträckning. Detta är märkligt då beslut ofta fattas genom omröstning och ibland med knapp majoritet. I efterhand vore det klokt att fundera på vilken utvecklingen blivit med en alternativ lösning. Även i beslutsfattande som riktar sig framåt i tiden borde ett kontrafaktualt grepp finnas med.