1945 August 6-12 the Bomb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WINTER 2013 - Volume 60, Number 4 the Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A

WINTER 2013 - Volume 60, Number 4 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay: the Crew

AFA’s Enola Gay Controversy Archive Collection www.airforcemag.com The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay From the Air Force Association’s Enola Gay Controversy archive collection Online at www.airforcemag.com The Crew The Commander Paul Warfield Tibbets was born in Quincy, Ill., Feb. 23, 1915. He joined the Army in 1937, became an aviation cadet, and earned his wings and commission in 1938. In the early years of World War II, Tibbets was an outstanding B-17 pilot and squadron commander in Europe. He was chosen to be a test pilot for the B-29, then in development. In September 1944, Lt. Col. Tibbets was picked to organize and train a unit to deliver the atomic bomb. He was promoted to colonel in January 1945. In May 1945, Tibbets took his unit, the 509th Composite Group, to Tinian, from where it flew the atomic bomb missions against Japan in August. After the war, Tibbets stayed in the Air Force. One of his assignments was heading the bomber requirements branch at the Pentagon during the development of the B-47 jet bomber. He retired as a brigadier general in 1966. In civilian life, he rose to chairman of the board of Executive Jet Aviation in Columbus, Ohio, retiring from that post in 1986. At the dedication of the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar- Hazy Center in December 2003, the 88-year-old Tibbets stood in front of the restored Enola Gay, shaking hands and receiving the high regard of visitors. (Col. Paul Tibbets in front of the Enola Gay—US Air Force photo) The Enola Gay Crew Airplane Crew Col. -

The Making of an Atomic Bomb

(Image: Courtesy of United States Government, public domain.) INTRODUCTORY ESSAY "DESTROYER OF WORLDS": THE MAKING OF AN ATOMIC BOMB At 5:29 a.m. (MST), the world’s first atomic bomb detonated in the New Mexican desert, releasing a level of destructive power unknown in the existence of humanity. Emitting as much energy as 21,000 tons of TNT and creating a fireball that measured roughly 2,000 feet in diameter, the first successful test of an atomic bomb, known as the Trinity Test, forever changed the history of the world. The road to Trinity may have begun before the start of World War II, but the war brought the creation of atomic weaponry to fruition. The harnessing of atomic energy may have come as a result of World War II, but it also helped bring the conflict to an end. How did humanity come to construct and wield such a devastating weapon? 1 | THE MANHATTAN PROJECT Models of Fat Man and Little Boy on display at the Bradbury Science Museum. (Image: Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory.) WE WAITED UNTIL THE BLAST HAD PASSED, WALKED OUT OF THE SHELTER AND THEN IT WAS ENTIRELY SOLEMN. WE KNEW THE WORLD WOULD NOT BE THE SAME. A FEW PEOPLE LAUGHED, A FEW PEOPLE CRIED. MOST PEOPLE WERE SILENT. J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER EARLY NUCLEAR RESEARCH GERMAN DISCOVERY OF FISSION Achieving the monumental goal of splitting the nucleus The 1930s saw further development in the field. Hungarian- of an atom, known as nuclear fission, came through the German physicist Leo Szilard conceived the possibility of self- development of scientific discoveries that stretched over several sustaining nuclear fission reactions, or a nuclear chain reaction, centuries. -

The Manhattan Project and Its Legacy

Transforming the Relationship between Science and Society: The Manhattan Project and Its Legacy Report on the workshop funded by the National Science Foundation held on February 14 and 15, 2013 in Washington, DC Table of Contents Executive Summary iii Introduction 1 The Workshop 2 Two Motifs 4 Core Session Discussions 6 Scientific Responsibility 6 The Culture of Secrecy and the National Security State 9 The Decision to Drop the Bomb 13 Aftermath 15 Next Steps 18 Conclusion 21 Appendix: Participant List and Biographies 22 Copyright © 2013 by the Atomic Heritage Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this book, either text or illustration, may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, reporting, or by any information storage or retrieval system without written persmission from the publisher. Report prepared by Carla Borden. Design and layout by Alexandra Levy. Executive Summary The story of the Manhattan Project—the effort to develop and build the first atomic bomb—is epic, and it continues to unfold. The decision by the United States to use the bomb against Japan in August 1945 to end World War II is still being mythologized, argued, dissected, and researched. The moral responsibility of scientists, then and now, also has remained a live issue. Secrecy and security practices deemed necessary for the Manhattan Project have spread through the govern- ment, sometimes conflicting with notions of democracy. From the Manhattan Project, the scientific enterprise has grown enormously, to include research into the human genome, for example, and what became the Internet. Nuclear power plants provide needed electricity yet are controversial for many people. -

Trinity Scientific Firsts

TRINITY SCIENTIFIC FIRSTS THE TRINITY TEST was perhaps the greatest scientifi c experiment ever. Seventy-fi ve years ago, Los Alamos scientists and engineers from the U.S., Britain, and Canada changed the world. July 16, 1945 marks the entry into the Atomic Age. PLUTONIUM: THE BETHE-FEYNMAN FORMULA: Scientists confi rmed the newly discovered 239Pu has attractive nuclear Nobel Laureates Hans Bethe and Richard Feynman developed the physics fi ssion properties for an atomic weapon. They were able to discern which equation used to estimate the yield of a fi ssion weapon, building on earlier production path would be most effective based on nuclear chemistry, and work by Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls. The equation elegantly encapsulates separated plutonium from Hanford reactor fuel. essential physics involved in the nuclear explosion process. PRECISION HIGH-EXPLOSIVE IMPLOSION FOUNDATIONAL RADIOCHEMICAL TO CREATE A SUPER-CRITICAL ASSEMBLY: YIELD ANALYSIS: Project Y scientists developed simultaneously-exploding bridgewire detonators Wartime radiochemistry techniques developed and used at Trinity with a pioneering high-explosive lens system to create a symmetrically provide the foundation for subsequent analyses of nuclear detonations, convergent detonation wave to compress the core. both foreign and domestic. ADVANCED IMAGING TECHNIQUES: NEW FRONTIERS IN COMPUTING: Complementary diagnostics were developed to optimize the implosion Human computers and IBM punched-card machines together calculated design, including fl ash x-radiography, the RaLa method, -

JUDGEMENT of the International Peoples' Tribunal on the Dropping

JUDGEMENT Of The International Peoples' Tribunal On the Dropping of Atomic Bombs On Hiroshima and Nagasaki July 16, 2007 Judges Lennox S. Hinds Carlos Vargas IE Masaji Prosecutors Mr. ADACHI Shuichi Mr. INOUE Masanobu Ms. SHIMONAKA Nami Mr. AKIMOTO Masahiro Mr. CHE Bong Tae Amicus Curiae Mr. OHKUBO Kenichi 1 PLAINTIFFS A-Bomb Survivors Citizens of Hiroshima Citizens of Nagasaki Any Other Supporters of A-Bomb Survivors DEFENDANTS UNITED STATES OF AMERICA US. President, Franklin D. Roosevelt U.S. President, Harry S. Truman James F. Byrnes, Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of War George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff Thomas T. Handy, Army Acting Chief of Staff Henrry H. Arnold, Commander of the Army Air Forces Carl A. Spaatz, Commander of the US Strategic Air Force Curtis E. LeMay, Commander of the 20th Bomber Command Paul W. Tibbets, Pilot of B-29 “Enola Gay” William S. Parsons, Weaponeer of B-29 “Enola Gay” Charles W. Sweeny, Pilot of B-29 “Book s Car” Frederick L. Ashworth, Weaponeer of B-29 “Bocks Car” Leslie R. Groves, Head of the Manhattan Project J. Robert Oppenheimer, Director of the Los Alamos Laboratory REGISTRY TSUBOI Sunao, SASAKI Takeya, TANAKA Yuki, FUNAHASHI Yoshie YOKOHARA Yukio, TOSHIMOTO Katsumi, OKUHARA Hiromi KUNO Naruaki, HINADA Seishi 2 A: Universal Jurisdiction of the Court 1. In accordance with Article 2 paragraph (1) of the Charter of the International Peoples' Tribunal on the Dropping of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Tribunal has jurisdiction over crimes committed against the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the victims of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and August 9, 1945, respectively. -

Trivia Questions

TRIVIA QUESTIONS Submitted by: ANS Savannah River - A. Bryson, D. Hanson, B. Lenz, M. Mewborn 1. What was the code name used for the first U.S. test of a dry fuel hydrogen bomb? Castle Bravo 2. What was the name of world’s first artificial nuclear reactor to achieve criticality? Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1), I also seem to recall seeing/hearing them referred to as “number one,” “number two,” etc. 3. How much time elapsed between the first known sustained nuclear chain reaction at the University of Chicago and the _____ Option 1: {first use of this new technology as a weapon} or Option 2: {dropping of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima} A3) First chain reaction = December 2nd 1942, First bomb-drop = August 6th 1945 4. Some sort of question drawing info from the below tables. For example, “what were the names of the other aircraft that accompanied the Enola Gay (one point for each correct aircraft name)?” Another example, “What was the common word in the call sign of the pilots who flew the Japanese bombing missions?” A4) Screenshots of tables from the Wikipedia page “Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki” Savannah River Trivia / Page 1 of 18 5. True or False: Richard Feynman’s name is on the patent for a nuclear powered airplane? (True) 6. What is the Insectary of Bobo-Dioulasso doing to reduce the spread of sleeping sickness and wasting diseases that affect cattle using a nuclear technique? (Sterilizing tsetse flies; IAEA.org) 7. What was the name of the organization that studied that radiological effects on people after the atomic bombings? Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission 8. -

Smithsonian and the Enola

An Air Force Association Special Report The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay The Air Force Association The Air Force Association (AFA) is an independent, nonprofit civilian organiza- tion promoting public understanding of aerospace power and the pivotal role it plays in the security of the nation. AFA publishes Air Force Magazine, sponsors national symposia, and disseminates infor- mation through outreach programs of its affiliate, the Aerospace Education Founda- tion. Learn more about AFA by visiting us on the Web at www.afa.org. The Aerospace Education Foundation The Aerospace Education Foundation (AEF) is dedicated to ensuring America’s aerospace excellence through education, scholarships, grants, awards, and public awareness programs. The Foundation also publishes a series of studies and forums on aerospace and national security. The Eaker Institute is the public policy and research arm of AEF. AEF works through a network of thou- sands of Air Force Association members and more than 200 chapters to distrib- ute educational material to schools and concerned citizens. An example of this includes “Visions of Exploration,” an AEF/USA Today multi-disciplinary sci- ence, math, and social studies program. To find out how you can support aerospace excellence visit us on the Web at www. aef.org. © 2004 The Air Force Association Published 2004 by Aerospace Education Foundation 1501 Lee Highway Arlington VA 22209-1198 Tel: (703) 247-5839 Produced by the staff of Air Force Magazine Fax: (703) 247-5853 Design by Guy Aceto, Art Director An Air Force Association Special Report The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay By John T. Correll April 2004 Front cover: The huge B-29 bomber Enola Gay, which dropped an atomic bomb on Japan, is one of the world’s most famous airplanes. -

Tinian: Not Just an Island in the Pacific

TINIAN: NOT JUST AN ISLAND IN THE PACIFIC It is a small island, less than 40 square miles, a flat green dot in the vastness of Pacific blue. Fly over it and you notice a slash across its north end of uninhabited bush, a long thin line that looks like an overgrown dirt runway. If you didn't know what it was, you wouldn't give it a second glance out your airplane window. On the ground, you see the runway isn't dirt but tarmac and crushed limestone, abandoned with weeds sticking out of it. Yet this is arguably the most historical airstrip on earth. This is where World War II was won. This is Runway Able On July 24, 1944, 30,000 US Marines landed on the beaches of Tinian. Eight days later, over 8,000 of the 8,800 Japanese soldiers on the island were dead (vs. 328 Marines), and four months later the Seabees had built the busiest airfield of WWII - dubbed North Field – enabling B-29 Superfortresses to launch air attacks on the Philippines, Okinawa, and mainland Japan. Late in the afternoon of August 5, 1945, a B-29 was maneuvered over a bomb loading pit, then after lengthy preparations, taxied to the east end of North Field's main runway, Runway Able, and at 2:45am in the early morning darkness of August 6, took off. The B-29 was piloted by Col. Paul Tibbets of the US Army Air Force, who had named the plane after his mother, Enola Gay. The crew named the bomb they were carrying Little Boy. -

Weapon Physics Division

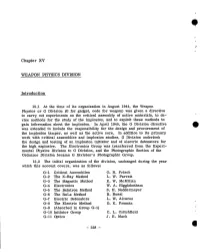

-!! Chapter XV WEAPON PHYSICS DIVISION Introduction 15.1 At the time of its organization in August 1944, the Weapon Physics or G Division (G for gadget, code for weapon) was given a directive to carry out experiments on the critical assembly of active materials, to de- vise methods for the study of the implosion, and to exploit these methods to gain information about the implosion. In April 1945, the G Division directive was extended to fnclude the responsibility for the design and procurement of the hnplosion tamper, as well as the active core. In addition to its primary work with critical assemblies and implosion studies, G Division undertook the design and testing of an implosion initiator and of electric detonators for the high explosive. The Electronics Group was transferred from the Experi- mental Physics Division to G Division, and the Photographic Section of the Ordnance Division became G Divisionts Photographic Group. 15.2 The initial organization of the division, unchanged during the year which this account covers, was as follows: G-1 Critical Assemblies O. R. Frisch G-2 The X-Ray Method L. W. Parratt G-3 The Magnetic Method E. W. McMillan G-4 Electronics W. A. Higginbotham G-5 The Betatron Method S. H. Neddermeyer G-6 The RaLa Method B. ROSSi G-7 Electric Detonators L. W. Alvarez G-8 The Electric Method D. K. Froman G-9 (Absorbed in Group G-1) G-10 Initiator Group C. L. Critchfield G-n Optics J. E. Mack - 228 - 15.3 For the work of G Division a large new laboratory building was constructed, Gamma Building. -

Nagasaki and the Hibakusha Experience of Sumiteru Taniguchi: the Painful Struggles and Ultimate Triumphs of Nagasaki Hibakusha

Volume 18 | Issue 16 | Number 1 | Article ID 5447 | Aug 15, 2020 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Nagasaki and the Hibakusha Experience of Sumiteru Taniguchi: The Painful Struggles and Ultimate Triumphs of Nagasaki Hibakusha Sumiteru Taniguchi Introduction by Peter J. Kuznick Abstract: Sumiteru Taniguchi was one of the Many of the more than 250,000 who lived in “lucky” ones. He lived a long and productive Nagasaki on August 9, 1945 were not so lucky. life. He married and fathered two healthy Tens of thousands were killed instantly by the children who gave him four grandchildren and plutonium core atomic bomb the U.S. dropped two great grandchildren. He had a long career that day from the B29 Bockscar, captained by in Japan’s postal and telegraph services. As a Major Charles Sweeney. The bomb, nicknamed leader in Japan’s anti-nuclear movement, he “Fat Man,” exploded with a force equivalent to addressed thousands of audiences and21 kilotons of TNT and wiped out an area that covered three square miles, shattering hundreds of thousands of people. Many of the windows eleven miles away. Some 74,000 were more than 250,000 who lived in Nagasaki on dead by the end of the year. The death toll August 9, 1945 were not so lucky. reached 140,000 by 1950. Included among the victims were thousands of Korean slave Keywords: Nagasaki, atomic bomb, hibakusha, laborers, who toiled in Japanese mines, fields, Sumiteru Taniguchi, the atomic decision and factories. Since then, atomic bomb-related injuries and illnesses have claimed thousands more victims and caused immense suffering to Sumiteru Taniguchi was one of the “lucky” many of the survivors. -

Clinton Engineer Work – Central Facilities

v DOOK I - G~ERAL VOLUME ].2.. - CLINTCE mo IN~ /uRKS KAHHATTAK DISTRICT HISTORT '' BOCK I - GENERAL VQUIKS 1 2 - CLIKX0N HKClINBftR WORKS, CENTRAL FACILITIES CLASSIFICATION CANCELLED g f e e » « F ! ' 0 .. .............................. BY AUTHORITY PE DOE/OPC 00 So-/c?.>3 THIS DCCUMEM N£ ISTS OF 3 5 * PAGES N O ... 3 _OF_" f SERIES ./ * _____ ( N o . © * C o p y c-o>'*-e.c.'VeJk wo •fcordawt w,ewto G. H, +o KR.C. *-V J.o(y \,C)4r'j'^ V 1 3 7 5 2 FOREWORD This volume of the Uanh«tt*n L’i»trio t 8ifiW | hi.8 b««rj. prepared to dsfctrlta tt*e purpose, design, construction, development, cost, and func tions of the Central Facilities of the Gllnton Engineer Works, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Although the Central Facilities are described at length and in de tail In this volume, they may be identified briefly as eabradng the non- industrial features of the Clinton Engineer Works, existing only to pro vide the facilities and service;* mere or less common to American urban life. As the Central Facilities exist separately and apart from the in dustrial plants, they cannot be described logically in connection with the Manufacturing plants. The Central Facilities are highly important auxiliaries to the manufacturing plants, for without the services and facilities supplied, the resident population necessary for manning the plants could not be maintained. The text of the history of the Central Facilities Is divided into three major parts* A - General Introduction, B - T o m of Oak Ridge, and C - Area Facilities.