Smithsonian and the Enola

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 04 Newsletter

United States Atmospheric & Underwater Atomic Weapon Activities National Association of Atomic Veterans, Inc. 1945 “TRINITY“ “Assisting America’s Atomic Veterans Since 1979” ALAMOGORDO, N. M. Website: www.naav.com E-mail: [email protected] 1945 “LITTLE BOY“ HIROSHIMA, JAPAN R. J. RITTER - Editor April, 2012 1945 “FAT MAN“ NAGASAKI, JAPAN 1946 “CROSSROADS“ BIKINI ISLAND 1948 “SANDSTONE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “RANGER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1951 “GREENHOUSE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “BUSTER – JANGLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “TUMBLER - SNAPPER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “IVY“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1953 “UPSHOT - KNOTHOLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1954 “CASTLE“ BIKINI ISLAND 1955 “TEAPOT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1955 “WIGWAM“ OFFSHORE SAN DIEGO 1955 “PROJECT 56“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1956 “REDWING“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1957 “PLUMBOB“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1958 “HARDTACK-I“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1958 “NEWSREEL“ JOHNSTON ISLAND 1958 “ARGUS“ SOUTH ATLANTIC 1958 “HARDTACK-II“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1961 “NOUGAT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1962 “DOMINIC-I“ CHRISTMAS ISLAND JOHNSTON ISLAND 1965 “FLINTLOCK“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1969 “MANDREL“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1971 “GROMMET“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1974 “POST TEST EVENTS“ ENEWETAK CLEANUP ------------ “ IF YOU WERE THERE, YOU ARE AN ATOMIC VETERAN “ The Newsletter for America’s Atomic Veterans COMMANDER’S COMMENTS knowing the seriousness of the situation, did not register any Outreach Update: First, let me extend our discomfort, or dissatisfaction on her part. As a matter of fact, it thanks to the membership and friends of NAAV was kind of nice to have some of those callers express their for supporting our “outreach” efforts over the thanks for her kind attention and assistance. We will continue past several years. It is that firm dedication to to insure that all inquires, along these lines, are fully and our Mission-Statement that has driven our adequately addressed. -

The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay: the Crew

AFA’s Enola Gay Controversy Archive Collection www.airforcemag.com The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay From the Air Force Association’s Enola Gay Controversy archive collection Online at www.airforcemag.com The Crew The Commander Paul Warfield Tibbets was born in Quincy, Ill., Feb. 23, 1915. He joined the Army in 1937, became an aviation cadet, and earned his wings and commission in 1938. In the early years of World War II, Tibbets was an outstanding B-17 pilot and squadron commander in Europe. He was chosen to be a test pilot for the B-29, then in development. In September 1944, Lt. Col. Tibbets was picked to organize and train a unit to deliver the atomic bomb. He was promoted to colonel in January 1945. In May 1945, Tibbets took his unit, the 509th Composite Group, to Tinian, from where it flew the atomic bomb missions against Japan in August. After the war, Tibbets stayed in the Air Force. One of his assignments was heading the bomber requirements branch at the Pentagon during the development of the B-47 jet bomber. He retired as a brigadier general in 1966. In civilian life, he rose to chairman of the board of Executive Jet Aviation in Columbus, Ohio, retiring from that post in 1986. At the dedication of the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar- Hazy Center in December 2003, the 88-year-old Tibbets stood in front of the restored Enola Gay, shaking hands and receiving the high regard of visitors. (Col. Paul Tibbets in front of the Enola Gay—US Air Force photo) The Enola Gay Crew Airplane Crew Col. -

The Manhattan Project and Its Legacy

Transforming the Relationship between Science and Society: The Manhattan Project and Its Legacy Report on the workshop funded by the National Science Foundation held on February 14 and 15, 2013 in Washington, DC Table of Contents Executive Summary iii Introduction 1 The Workshop 2 Two Motifs 4 Core Session Discussions 6 Scientific Responsibility 6 The Culture of Secrecy and the National Security State 9 The Decision to Drop the Bomb 13 Aftermath 15 Next Steps 18 Conclusion 21 Appendix: Participant List and Biographies 22 Copyright © 2013 by the Atomic Heritage Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this book, either text or illustration, may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, reporting, or by any information storage or retrieval system without written persmission from the publisher. Report prepared by Carla Borden. Design and layout by Alexandra Levy. Executive Summary The story of the Manhattan Project—the effort to develop and build the first atomic bomb—is epic, and it continues to unfold. The decision by the United States to use the bomb against Japan in August 1945 to end World War II is still being mythologized, argued, dissected, and researched. The moral responsibility of scientists, then and now, also has remained a live issue. Secrecy and security practices deemed necessary for the Manhattan Project have spread through the govern- ment, sometimes conflicting with notions of democracy. From the Manhattan Project, the scientific enterprise has grown enormously, to include research into the human genome, for example, and what became the Internet. Nuclear power plants provide needed electricity yet are controversial for many people. -

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

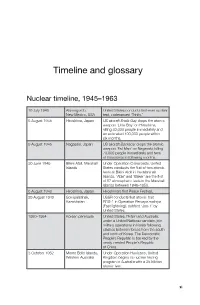

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

Trinity and Beyond: the Atomic Bomb Movie

Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie 1. Why did scientists detonate 100 tons of TNT be- 9. How many died in Hiroshima? 20. How heavy was the housing that contained the fore they tested their bombs? Mike test bomb? 10. How many buildings were destroyed? 2. Who was put in charge of the Manhattan Project? 21. During the 1953 Nevada desert tests, why did the smaller yield bomb cause more damage than the 11. How many died in Nagasaki? larger yield bomb? 3. Was the scientist Edward Teller at first in favor of the bomb project? 12. How many were injured? 22. What were the scientists studying when they ex- ploded bombs in the ocean off of San Diego? 4. Did he ever regret working on the bombs? 13. What percent of the buildings were destroyed? 23. On later Pacific Island tests, why were floating 5. When the first test bomb exploded at the Trinity barges needed to carry the bombs? site in New Mexico, what were the values associated 14. During Operation Crossroads, which caused with each of the following? more damage; the airdrop, or the underwater explo- sion? 24. How high up was the Teak test shot detonated? a) temperature: b) pressure: 15. What was the purpose of Operation Sandstone? 25. What happened in the atmosphere as a result? c) distance at which a person would go temporarily blind: d) number of times greater than the explosion of 100 16. In what year did Russia first test an atomic 26. How far away were these effects felt, and how tons of TNT: bomb? long did they last? 6. -

Fiscal Year 2008 Department of the Air Force Financial Statements and Notes

Table of Contents Message from the Secretary of the Air Force ..........................................................................................................................ii Message from the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Financial Management and Comptroller .................................iii Management Discussion and Analysis Air Force Heritage ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Air Force Core Values ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Air Force Critical Capabilities ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Air Force Goals ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Air Force in Action – FY 2008 ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Reinvigorate the Air Force Nuclear Enterprise ................................................................................................. 3 Partner With The Joint and Coalition Team to Win Today’s Fight .................................................................. 3 Develop and Care for Airmen and Their Families ......................................................................................... -

Tomoe Otsuki

Volume 13 | Issue 32 | Number 2 | Article ID 4356 | Aug 10, 2015 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Politics of Reconstruction and Reconciliation in U.S-Japan Relations—Dismantling the Atomic Bomb Ruins of Nagasaki’s Urakami Cathedral Tomoe Otsuki Abstract: This paper explores the politics surrounding the dismantling of the ruins of Nagasaki’s Urakami Cathedral. It shows how U.S-Japan relations in the mid-1950s shaped the 1958 decision by the Catholic community of Urakami to dismantle and subsequently to reconstruct the ruins. The paper also assesses the significance of the struggle over the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral for understanding the respective responses to atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It further casts new light on the wartime role of the Catholic Church and of Nagai Takashi. Keywords: Nagasaki, Atomic Bomb, Urakami Cathedral, the People-to-People program, Lucky Dragon # 5 incident, Japanese antinuclear movement, the peaceful use of nuclear energy, sister city relation between Nagasaki and St. Paul, U.S.-Japan Security Alliance. The two photographs below depict the remnants of the Urakami Cathedral following the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Both were taken in 1953 by Takahara Itaru, a former Mainichi Shimbun photographer as well as a Remnants of the Southern Wall and statues of the Nagasaki hibakusha. Most of the children saints of Urakami Cathedral playing beside the ruins were born after the Photo courtesy of Takahara Itaru atomic bombing and grew up in Urakami’s atomic field. Takahara’s photographs capture the remnants of the cathedral in shaping the Children play in remnants of belfry of Urakami postwar landscape and lives of people in and Cathedral 1 around Urakami. -

Bob Farquhar

1 2 Created by Bob Farquhar For and dedicated to my grandchildren, their children, and all humanity. This is Copyright material 3 Table of Contents Preface 4 Conclusions 6 Gadget 8 Making Bombs Tick 15 ‘Little Boy’ 25 ‘Fat Man’ 40 Effectiveness 49 Death By Radiation 52 Crossroads 55 Atomic Bomb Targets 66 Acheson–Lilienthal Report & Baruch Plan 68 The Tests 71 Guinea Pigs 92 Atomic Animals 96 Downwinders 100 The H-Bomb 109 Nukes in Space 119 Going Underground 124 Leaks and Vents 132 Turning Swords Into Plowshares 135 Nuclear Detonations by Other Countries 147 Cessation of Testing 159 Building Bombs 161 Delivering Bombs 178 Strategic Bombers 181 Nuclear Capable Tactical Aircraft 188 Missiles and MIRV’s 193 Naval Delivery 211 Stand-Off & Cruise Missiles 219 U.S. Nuclear Arsenal 229 Enduring Stockpile 246 Nuclear Treaties 251 Duck and Cover 255 Let’s Nuke Des Moines! 265 Conclusion 270 Lest We Forget 274 The Beginning or The End? 280 Update: 7/1/12 Copyright © 2012 rbf 4 Preface 5 Hey there, I’m Ralph. That’s my dog Spot over there. Welcome to the not-so-wonderful world of nuclear weaponry. This book is a journey from 1945 when the first atomic bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert to where we are today. It’s an interesting and sometimes bizarre journey. It can also be horribly frightening. Today, there are enough nuclear weapons to destroy the civilized world several times over. Over 23,000. “Enough to make the rubble bounce,” Winston Churchill said. The United States alone has over 10,000 warheads in what’s called the ‘enduring stockpile.’ In my time, we took care of things Mano-a-Mano. -

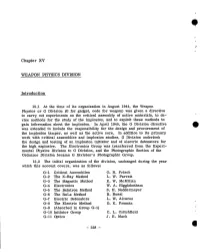

Weapon Physics Division

-!! Chapter XV WEAPON PHYSICS DIVISION Introduction 15.1 At the time of its organization in August 1944, the Weapon Physics or G Division (G for gadget, code for weapon) was given a directive to carry out experiments on the critical assembly of active materials, to de- vise methods for the study of the implosion, and to exploit these methods to gain information about the implosion. In April 1945, the G Division directive was extended to fnclude the responsibility for the design and procurement of the hnplosion tamper, as well as the active core. In addition to its primary work with critical assemblies and implosion studies, G Division undertook the design and testing of an implosion initiator and of electric detonators for the high explosive. The Electronics Group was transferred from the Experi- mental Physics Division to G Division, and the Photographic Section of the Ordnance Division became G Divisionts Photographic Group. 15.2 The initial organization of the division, unchanged during the year which this account covers, was as follows: G-1 Critical Assemblies O. R. Frisch G-2 The X-Ray Method L. W. Parratt G-3 The Magnetic Method E. W. McMillan G-4 Electronics W. A. Higginbotham G-5 The Betatron Method S. H. Neddermeyer G-6 The RaLa Method B. ROSSi G-7 Electric Detonators L. W. Alvarez G-8 The Electric Method D. K. Froman G-9 (Absorbed in Group G-1) G-10 Initiator Group C. L. Critchfield G-n Optics J. E. Mack - 228 - 15.3 For the work of G Division a large new laboratory building was constructed, Gamma Building. -

Foundation Document Manhattan Project National Historical Park Tennessee, New Mexico, Washington January 2017 Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Manhattan Project National Historical Park Tennessee, New Mexico, Washington January 2017 Foundation Document MANHATTAN PROJECT NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK Hanford Washington ! Los Alamos Oak Ridge New Mexico Tennessee ! ! North 0 700 Kilometers 0 700 Miles More detailed maps of each park location are provided in Appendix E. Manhattan Project National Historical Park Contents Mission of the National Park Service 1 Mission of the Department of Energy 2 Introduction 3 Part 1: Core Components 4 Brief Description of the Park. 4 Oak Ridge, Tennessee. 5 Los Alamos, New Mexico . 6 Hanford, Washington. 7 Park Management . 8 Visitor Access. 8 Brief History of the Manhattan Project . 8 Introduction . 8 Neutrons, Fission, and Chain Reactions . 8 The Atomic Bomb and the Manhattan Project . 9 Bomb Design . 11 The Trinity Test . 11 Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan . 12 From the Second World War to the Cold War. 13 Legacy . 14 Park Purpose . 15 Park Signifcance . 16 Fundamental Resources and Values . 18 Related Resources . 22 Interpretive Themes . 26 Part 2: Dynamic Components 27 Special Mandates and Administrative Commitments . 27 Special Mandates . 27 Administrative Commitments . 27 Assessment of Planning and Data Needs . 28 Analysis of Fundamental Resources and Values . 28 Identifcation of Key Issues and Associated Planning and Data Needs . 28 Planning and Data Needs . 31 Part 3: Contributors 36 Appendixes 38 Appendix A: Enabling Legislation for Manhattan Project National Historical Park. 38 Appendix B: Inventory of Administrative Commitments . 43 Appendix C: Fundamental Resources and Values Analysis Tables. 48 Appendix D: Traditionally Associated Tribes . 87 Appendix E: Department of Energy Sites within Manhattan Project National Historical Park . -

Activity 7: Can the Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Be Justified?

Activity 7: Instructions World War II Activity 7: Can the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki be justified? Purpose To examine historic evidence to draw conclusions and reach informed opinions. Curriculum Focus History - Understand the diverse experiences and ideas, beliefs and attitudes of men, women and children in past societies, identify and explain change and continuity within and across periods of history identify, select and use a range of historical sources, evaluate the sources used in order to reach reasoned conclusions, present and organise accounts and explanations about the past that are coherent, structured and substantiated, use chronological conventions and historical vocabulary. Communication – Oracy, reading, writing. ICT - Structure, refine and communicate information, produce a presentation. Thinking Skills - Identify the problem and set the questions to resolve it, suggest a range of options as to where and how to find relevant information and ideas, ask probing questions, build on existing skills, knowledge and understanding, evaluate options, use prior knowledge to explain links between cause and effect and justify inferences/ predictions, identify and assess bias and reliability, consider others’ views to inform opinions and decisions, determine success criteria and give some justification for choice. P4C – Feeling empathy. Materials Included in this pack: Activity sheet 7a – Student introduction Activity sheet 7b – Hiroshima before and after the bombing Activity sheet 7c – Detonations of the atomic bombs Activity sheet 7d – The effects of the atomic bombs (Warning: Contains graphic images of survivors of the bombings) Activity sheet 7e – Enola Gay and Bockscar Activity sheet 7f – Statistics Activity sheet 7g – Eyewitness accounts You will also need: Internet access, rope Groupings Whole class, four or five ©Imaginative Minds Ltd. -

A History of the United States Caribbean Defense Command (1941-1947) Cesar A

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-25-2016 A History of the United States Caribbean Defense Command (1941-1947) Cesar A. Vasquez Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC000266 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Latin American History Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Vasquez, Cesar A., "A History of the United States Caribbean Defense Command (1941-1947)" (2016). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2458. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2458 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida A HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES CARIBBEAN DEFENSE COMMAND (1941-1947) A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Cesar A. Vasquez 2016 To: Dean John F. Stack School of International and Public Affairs This dissertation, written by Cesar A. Vasquez, and entitled A History of the United States Caribbean Defense Command (1941-1947), having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Victor Uribe _______________________________________ April Merleaux _______________________________________ Eduardo Gamarra _______________________________________ Kenneth Lipartito, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 25, 2016 The dissertation of Cesar A.