Little Boy, the Antichristchild. the Beast in the Nuclear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of an Atomic Bomb

(Image: Courtesy of United States Government, public domain.) INTRODUCTORY ESSAY "DESTROYER OF WORLDS": THE MAKING OF AN ATOMIC BOMB At 5:29 a.m. (MST), the world’s first atomic bomb detonated in the New Mexican desert, releasing a level of destructive power unknown in the existence of humanity. Emitting as much energy as 21,000 tons of TNT and creating a fireball that measured roughly 2,000 feet in diameter, the first successful test of an atomic bomb, known as the Trinity Test, forever changed the history of the world. The road to Trinity may have begun before the start of World War II, but the war brought the creation of atomic weaponry to fruition. The harnessing of atomic energy may have come as a result of World War II, but it also helped bring the conflict to an end. How did humanity come to construct and wield such a devastating weapon? 1 | THE MANHATTAN PROJECT Models of Fat Man and Little Boy on display at the Bradbury Science Museum. (Image: Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory.) WE WAITED UNTIL THE BLAST HAD PASSED, WALKED OUT OF THE SHELTER AND THEN IT WAS ENTIRELY SOLEMN. WE KNEW THE WORLD WOULD NOT BE THE SAME. A FEW PEOPLE LAUGHED, A FEW PEOPLE CRIED. MOST PEOPLE WERE SILENT. J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER EARLY NUCLEAR RESEARCH GERMAN DISCOVERY OF FISSION Achieving the monumental goal of splitting the nucleus The 1930s saw further development in the field. Hungarian- of an atom, known as nuclear fission, came through the German physicist Leo Szilard conceived the possibility of self- development of scientific discoveries that stretched over several sustaining nuclear fission reactions, or a nuclear chain reaction, centuries. -

Program | Abstracts | Lecturers

11 March 2021 International conference ‘NATIONAL FORGETTING AND MEMORY: THE DESTRUCTION OF "NATIONAL" MONUMENTS FROM A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE’ Program | Abstracts | Lecturers Organised by NISE and the Museum at the Yser In cooperation with: INDEX OF LECTURES KEY NOTE 1. Monumentality and Its Discontents: How the Past is Unforgotten. A. Rigney SESSION 1. Nation vs Regional vs Local Memories Chaired by Bruno De Wever City Monuments in Contemporary Kharkiv: Construction of the National and Regional Memory. V. Sukovata Nationalising Scorched Earth – Memory and destruction of monuments from Vukovar to Knin. M. Piasek Fascist monuments and their divided memories in Trieste and Bolzano. I. Pupella-Noguès SESSION 2. Nation-state, ideology and monuments Chaired by Chantal Kesteloot Reactions and counter reactions: The removal of Hoxha’s monuments and Albania’s tortuous transition. K. Këlliçi Present absence or absent presence. Monuments dedicated to the Yugoslav partisan struggle between future present and present perfect. L. Lovrenčić. and T. Pupovac «War on monuments» in Poland and its implications for the national historical policy. M. Pavlova KEY NOTE 2. Animated Stones: drawing a picture of the “IJzertoren’s” destruction via the lens of editorial cartoons. K. Swerts SESSION 3. Global and contemporary perspectives Chaired by K. Swerts A Knee on the Neck: Problematic Commemorative Practices in the United States. K. Shelby Set in Stone? Monuments, National Identity & John A. Macdonald. C. Spicer A Fractured Door: The Contested History of the IRS. J. Dawson Portraying and preserving the South African past – a monumental challenge. A. Bailey SESSION 4. The politics of resurrection Chaired by Marnix Beyen Staged reconstruction: On the scenography of the IJzertoren’s building site. -

Demystifying the Number of the Beast in the Book of Revelation: Examples of Ancient Cryptology and the Interpretation of the “666” Conundrum

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Engineering and Information Faculty of Informatics - Papers (Archive) Sciences 2010 Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum M G. Michael University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Michael, M G.: Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum 2010. https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/3585 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum Abstract As the year 2000 came and went, with the suitably forecasted fuse-box of utopian and apocalyptic responses, the question of "666" (Rev 13:18) was once more brought to our attention in different ways. Biblical scholars, for instance, focused again on the interpretation of the notorious conundrum and on the Traditionsgeschichte of Antichrist. For some of those commentators it was a reply to the outpouring of sensationalist publications fuelled by the millennial mania. This paper aims to shed some light on the background, the sources, and the interpretation of the “number of the beast”. It explores the ancient techniques for understanding the conundrum including: gematria, arithmetic, symbolic, and riddle-based solutions. -

(P)115 and the Number of the Beast

Tyndale Bulletin 58.1 (2007) 151-153. P115 AND THE NUMBER OF THE BEAST P. J. Williams Summary In Revelation 13:18 the occurrence of the number 616 in P115 has been taken as offering support to the view that the number refers to Nero. Here, an alternative or perhaps additional explanation of the number 616 is given by the suggestion that this number visually mimics designations of Jesus. 1. Introduction The number of conjectures as to the significance of the number of the Beast in Revelation 13:18 almost seems to exceed 666. Scholars now generally agree that a solution to the question of its meaning will need to invoke some form of gematria, since the letters of both the Greek and Hebrew alphabets had numerical significance. Irenaeus records, with varying levels of approval,1 the suggestions that 666 corresponded ευανθας λατεινος τειταν to , and , but none of these commands modern support. Recent scholarship has more readily given attention to various possibilities based on the Hebrew alphabet. One of the consistently popular proposals of the modern period – one which Charles attributes to four scholars independently – is that ק ו ר נ נרון קסר 666 stands for Nero Caesar = (2× [50], 2× [200], [6], ס [100], [60].2 This interpretation has gained support through the exist- ence of a textual variant giving the number as 616 found in ms C and 1 Irenaeus, Adv. Haer. 5.30.3. 2 R. H. Charles, The Revelation of St. John (ICC; Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1920): 367. The scholars mentioned by Charles are Holtzmann, Benary, Hitzig and Reuss. -

Observations on 666 in the Old Testament

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Engineering and Information Faculty of Informatics - Papers (Archive) Sciences 6-1999 Observations on 666 in the Old Testament M. G. Michael University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Michael, M. G.: Observations on 666 in the Old Testament 1999. https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/672 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Observations on 666 in the Old Testament Disciplines Physical Sciences and Mathematics Publication Details This article was originally published as Michael, MG, Observations on 666 in the Old Testament, Bulletin of Biblical Studies, 18, January-June 1999, 33-39. This journal article is available at Research Online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/672 RULLeTIN OF RIRLICkL STuDies Vol. 18, January - June 1999, Year 28 CONTENTS Prof. George Rigopoulos, ...~ Obituary for Oscar Cullmann 5 .., Prof. Savas Agourides, The Papables of Preparedness in Matthew's Gospel 18 Michael G. Michael, Observations on 666 in the Old Testament. 33 Prof. George Rigopoulos, Jesus and the Greeks (Exegetical Approach of In. 12,20-26) (Part B'). .. 40 Zoltan Hamar, Grace more immovable than the mountains 53 Raymond Goharghi, The land of Geshen in Egypt. The Ixos 99 Bookreviews: Prof. S. Agourides: Jose Saramagu, The Gospel according to Jesus - Karen Armstrong, In the Beginning, A new Interpretation ojthe Book ojGenesis ; 132 EDITIONS «ARTOS ZOES» ATHENS RULLeTIN OF RIRLIC~L STuDies Vol. -

Mussolini and Rome in the Premillennial Imagination

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 6-24-2020 The Beast And The Revival Of Rome: Mussolini And Rome In The Premillennial Imagination Jon Stamm Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Stamm, Jon, "The Beast And The Revival Of Rome: Mussolini And Rome In The Premillennial Imagination" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 1312. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1312 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BEAST AND THE REVIVAL OF ROME: MUSSOLINI AND ROME IN THE PREMILLENNIAL IMAGINATION JON STAMM 130 Pages Premillennial dispensationalism became immensely influential among American Protestants who saw themselves as defenders of orthodoxy. As theological conflict heated up in the early 20th century, dispensationalism’s unique eschatology became one of the characteristic features of the various strands of “fundamentalists” who fought against modernism and the perceived compromises of mainline Protestantism. Their embrace of the dispensationalist view of history and Biblical prophecy had a significant effect on how they interpreted world events and how they lived out their faith. These fundamentalists established patterns of interpretation that in the second half of the 20th century would fuel the emergence of a politically influential form of Christian Zionism. -

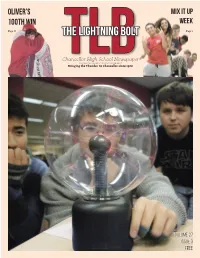

The Lightning Bolt Page 2

Oliver’s Mix It Up 100th win Week Page 17 The Lightning Bolt Page 2 Chancellor High School Newspaper TLB6300 Harrison Road, Fredericksburg, VA 22407 Bringing the Thunder to Chancellor since 1988 Volume 27 Issue 3 FREE 1 November 2014 what IS HAPPENING? Photo by Neil Schubel Neil Photo by Kids flocked to Mix It Up tables during lunch to take their pledge. Mix It Up week challenges kids to identify, cross and challenge social boundaries. Many students took thier pledge to mix it up in the week of November 10th till the 14th. Photo by Yearbook Staff Yearbook Photo by Photo by Neil Schubel Neil Photo by Schubel Neil Photo by Schubel Neil Photo by Tyler Jacobs models his painted Kenneth Ryan was spotted in the Jamie Smith in the process of a Joshua Edney jumps in the air in cheek in Mix It Up Week. halls with a fake skull. painted heart in Mix It Up Week. excitement. Photo courtesy of April Kniebbe April of Photo courtesy Nostalgia November! Who remembers the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge? The football coaches certainly do as they accepted the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge this July. A few players dumped the buckets as the team stood around to watch their coaches get ice buckets dumped on their heads. November 2014 2 Contents Editorial By Neil Schubel coming of winter if you look to by Chancellor’s Sociology Class Mrs. Gattie Editor-in-Chief some cases in states like New was also a huge success as near- Adviser It will ruin the happiest of York that are getting up to four ly 800 students took the pledge mornings waking up and realiz- feet of snow). -

Antichrist As (Anti)Charisma: Reflections on Weber and the ‘Son of Perdition’

Religions 2013, 4, 77–95; doi:10.3390/rel4010077 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article Antichrist as (Anti)Charisma: Reflections on Weber and the ‘Son of Perdition’ Brett Edward Whalen Department of History, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 3193, Chapel Hill, NC, 27707, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-919-962-2383 Received: 20 December 2012; in revised form: 25 January 2013 / Accepted: 29 January 2013 / Published: 4 February 2013 Abstract: The figure of Antichrist, linked in recent US apocalyptic thought to President Barack Obama, forms a central component of Christian end-times scenarios, both medieval and modern. Envisioned as a false-messiah, deceptive miracle-worker, and prophet of evil, Antichrist inversely embodies many of the qualities and characteristics associated with Max Weber’s concept of charisma. This essay explores early Christian, medieval, and contemporary depictions of Antichrist and the imagined political circumstances of his reign as manifesting the notion of (anti)charisma, compelling but misleading charismatic political and religious leadership oriented toward damnation rather than redemption. Keywords: apocalypticism; charisma; Weber; antichrist; Bible; US presidency 1. Introduction: Obama, Antichrist, and Weber On 4 November 2012, just two days before the most recent US presidential election, Texas “Megachurch” pastor Robert Jeffress (1956– ) proclaimed that a vote for the incumbent candidate Barack Obama (1961– ) represented a vote for the coming of Antichrist. “President Obama is not the Antichrist,” Jeffress qualified to his listeners, “But what I am saying is this: the course he is choosing to lead our nation is paving the way for the future reign of Antichrist” [1]. -

BIBLE PROPHECY 666 and the Mark of the Beast

BIBLE PROPHECY 666 and the Mark of the Beast www.makinglifecount.net Revelation 13:16-18 says, "And he causes all, the small and the great, and the rich and the poor, and the free men and the slaves, to be given a mark on their right hand, or on their forehead, and he provides that no one should be able to buy or to sell, except the one who has the mark, the name of the beast or the number of his name. Here is wisdom. Let him who has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for the number is that of a man; and his number is six hundred and sixty-six." Three things are mentioned in this passage: 1. The mark of the beast 2. The name of the beast 3. The number of his name The Mark of the Beast is not 666 but a mark that everyone must have to buy or sell. What kind of mark it will be is not stated. It may be an emblem of his kingdom or some kind of computer chip or code. 666 is the number of the Beast's name. The number of the beast is the number of a man. That means that the beast is not a political system, a country, a computer, etc., but a man—the Antichrist. This verse informs us that the Antichrist will control the world's economy with some kind of mark or symbol, which everyone will be required to take. No one will be able to buy or sell without having the mark on his or her right hand or forehead. -

The Mark of the Beast

The Mark of the Beast n the Bible, the Book of Revelation cryptically asserts the number 666 to be “the number of a man” who is associated I with the “beast.” The reader is then challenged to decipher the symbolism of this number—a challenge that has inspired mystics and would-be prophets ever since. Today, nearly two thousand years after the Book of Revelation was written, the Mark of the Beast remains an enigma to most. The long list of presumptions and theories surrounding the Mark, while solidly grounded in the popular culture and thinking of our day, fail to provide any specific or biblically sound explanation for this puzzle. Perhaps the Mark of the Beast, like some of the other prophetic riddles, was intended to remain shrouded in mystery until the ap- pointed time. An Invaluable Insight In previous chapters, it has been proposed that Islam is the key to understanding many of the prophecies concerning the end of the age. Might this also be the case regarding the Mark of the Beast? A recent discovery has led many to believe so. In what is considered by some to be the ultimate in irony, it appears as though a man who was once a devout Muslim may have solved one of the great Bible mysteries of all time. In this chapter, we are going to examine what is believed by many to be the first truly plausible explanation for the infamous Mark of the Beast. The source of this discovery is an ex-Muslim turned Christian who noticed something very peculiar while studying 199 From Abraham to Armageddon a specific passage in the Book of Revelation. -

2013 Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, Ma

The Loomis Chaffee School 2012-2013 Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, March 27, 2013 Alpine Skiing Boys Basketball Girls Basketball Boys Hockey Girls Hockey Boys Swimming Girls Swimming Boys Squash Girls Squash Wrestling Loomis Chaffee Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, March 27, 2013 6:30 p.m. Loomis Dining Hall Tonight’s Program Welcome Remarks: Bob Howe ’80, Athletic Director Alpine Skiing: Jake Leyden Girls Squash: Naomi Appel Boys Squash: Elliot Beck Girls Swimming: Bob DeConinck Boys Swimming: Fred Seebeck Girls Hockey Liz Leyden Boys Hockey John Zavisza Boys Basketball Jim Dargati ‘85 Girls Basketball Adrian Stewart ‘90 Wrestling Ben Haldeman 2012-2013 Winter Athletic Award Winners Alpine Skiing All New England: Tucker Santoro, Sara Corsetti Most Valuable Skiier: Tucker Santoro Coaches’ Award: Theodora Cohen Boys Varsity Basketball All New England: Joe Stortini Coaches’ Award: Durelle Napier Coaches’ Award: Dale Reese Most Valuable Player: Joe Stortini Girls Varsity Basketball All New England: Steph Jones and Abby Pyne Most Valuable Player: Steph Jones Most Improved: Chynna Bailey Coaches’ Award: Brooke Marchitto Boys Varsity Hockey U.S.HR Prep School Player of the Year Danny Tirone All New England Team: Danny Tirone Most Valuable Player: Danny Tirone Coaches’ Award: EJ Culhane Coaches’ Award: Nick Miceli Golden Buoy: Stephen Picard Girls Varsity Hockey Coaches’ Award: Brittany Bugalski Coaches’ Award: Molly Strabley Boys Varsity Squash Most Valuable Player: Alex Steel Most Improved Player: Kevin Cha Coaches’ Award: -

A Secret Revealed

LESSON PLAN (Image: US Army/Air Force, public domain.) A SECRET REVEALED GRADE LEVEL: 7-12 TIME REQUIREMENT: 1-2 CLASS PERIODS INTRODUCTION OBJECTIVES After the United States dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima, Japan, In reading different letters about the atomic bomb sent the morning of August 6, 1945, the world learned of the great to and from a worker in the Manhattan Project, students secret behind the Manhattan Project. Even with thousands of should be able to determine how people from various people involved in the construction of atomic bombs, the secrecy backgrounds reacted to the news of its existence and around the manufacture of nuclear weapons remained tightly held. its use in combat. Students should also assess how the Outside of limited cases of espionage, news of the atomic bomb differing perspectives affected the way certain individuals went unnoticed among the general public until after the bombing reacted to the dropping of such bombs on Japanese of Hiroshima, and the dropping of Fat Man three days later on cities. By contrasting the views preserved in these Nagasaki. As knowledge of atomic weapons reached the general primary sources, students will be able to see how limited public, reactions varied widely. In this lesson, students will examine the knowledge of nuclear weapons was in 1945, how primary source materials from The National WWII Museum’s debates on use of the bomb emerged in the aftermath collection in which differing responses to the atomic bomb of the war, and how even those who participated in the appear. Looking at the letters of civilians living near Alamogordo, Manhattan Project had concerns about the existence of New Mexico, of a participant in the Manhattan Project, and of such weapons.