The Wound/Burn Guidelines –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nexobrid 2 G Powder and Gel for Gel

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 This medicinal product is subject to additional monitoring. This will allow quick identification of new safety information. Healthcare professionals are asked to report any suspected adverse reactions. See section 4.8 for how to report adverse reactions. 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT NexoBrid 2 g powder and gel for gel 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION One vial contains 2 g of concentrate of proteolytic enzymes enriched in bromelain, corresponding to 0.09 g/g concentrate of proteolytic enzymes enriched in bromelain after mixing (or 2 g/22 g gel). The proteolytic enzymes are a mixture of enzymes from the stem of Ananas comosus (pineapple plant). For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Powder and gel for gel. The powder is off-white to light tan. The gel is clear and colourless. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications NexoBrid is indicated for removal of eschar in adults with deep partial- and full-thickness thermal burns. 4.2 Posology and method of administration NexoBrid should only be applied by trained healthcare professionals in specialist burn centres. Posology 2 g NexoBrid powder in 20 g gel is applied to a burn wound area of 100 cm2. NexoBrid should not be applied to more than 15% Total Body Surface Area (TBSA) (see also section 4.4, Coagulopathy). NexoBrid should be left in contact with the burn for a duration of 4 hours. There is very limited information on the use of NexoBrid on areas where eschar remained after the first application. -

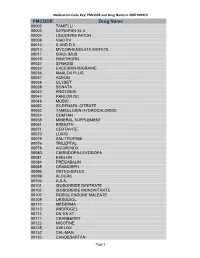

Medication Code Key: PMCODE and Drug Name in 2007 NHHCS Cdc-Pdf

Medication Code Key: PMCODE and Drug Name in 2007 NHHCS PMCODE Drug Name 00002 TAMIFLU 00003 DITROPAN XL II 00004 LIDODERM PATCH 00008 VIACTIV 00010 A AND D II 00013 MYCOPHENOLATE MOFETIL 00017 SIROLIMUS 00019 HAWTHORN 00027 SYNAGIS 00032 EXCEDRIN MIGRAINE 00036 MAALOX PLUS 00037 ACEON 00038 GLYSET 00039 SONATA 00042 PROTONIX 00044 PANLOR DC 00048 MOBIC 00052 SILDENAFIL CITRATE 00053 TAMSULOSIN HYDROCHLORIDE 00054 COMTAN 00058 MINERAL SUPPLEMENT 00061 BISMUTH 00071 CERTAVITE 00073 LUXIQ 00075 SAL-TROPINE 00076 TRILEPTAL 00078 AGGRENOX 00080 CARBIDOPA-LEVODOPA 00081 EXELON 00084 PREGABALIN 00085 ORAMORPH 00096 OSTEO-BIFLEX 00099 ALOCRIL 00100 A.S.A. 00101 ISOSORBIDE DINITRATE 00102 ISOSORBIDE MONONITRATE 00107 ROSIGLITAZONE MALEATE 00109 URSODIOL 00112 MEDERMA 00113 ANDROGEL 00114 DILTIA XT 00117 CRANBERRY 00123 NICOTINE 00125 AVELOX 00132 CAL-MAG 00133 CANDESARTAN Page 1 Medication Code Key: PMCODE and Drug Name in 2007 NHHCS PMCODE Drug Name 00148 PROLIXIN D 00149 D51/2 NS 00150 NICODERM CQ PATCH 00151 TUSSIN 00152 CEREZYME 00154 CHILDREN'S IBUPROFEN 00156 PROPOXACET-N 00159 KALETRA 00161 BISOPROLOL 00167 NOVOLIN N 00169 KETOROLAC TROMETHAMINE 00172 OPHTHALMIC OINTMENT 00173 ELA-MAX 00176 PREDNISOLONE ACETATE 00179 COLLOID SILVER 00184 KEPPRA 00187 OPHTHALMIC DROPS 00190 ABDEC 00191 HAPONAL 00192 SPECTRAVITE 00198 ENOXAPARIN SODIUM 00206 ACTONEL 00208 CELECOXIB 00209 GLUCOVANCE 00211 LEVALL 5.0 00213 PANTOPRAZOLE SODIUM 00217 TEMODAR 00218 CARBAMIDE PEROXIDE 00221 CHINESE HERBAL MEDS 00224 MILK AND MOLASSES ENEMA 00238 ZOLMITRIPTAN 00239 -

Advanced Textiles for Wound Care

Woodhead Publishing in Textiles: Number 85 Advanced textiles for wound care Edited by S. Rajendran Oxford Cambridge New Delhi © 2009 Woodhead Publishing Limited The Textile Institute and Woodhead Publishing The Textile Institute is a unique organisation in textiles, clothing and footwear. Incorporated in England by a Royal Charter granted in 1925, the Institute has individual and corporate members in over 90 countries. The aim of the Institute is to facilitate learning, recognise achievement, reward excellence and disseminate information within the global textiles, clothing and footwear industries. Historically, The Textile Institute has published books of interest to its members and the textile industry. To maintain this policy, the Institute has entered into partnership with Woodhead Publishing Limited to ensure that Institute members and the textile industry continue to have access to high calibre titles on textile science and technology. Most Woodhead titles on textiles are now published in collaboration with The Textile Institute. Through this arrangement, the Institute provides an Editorial Board which advises Woodhead on appropriate titles for future publication and suggests possible editors and authors for these books. Each book published under this arrangement carries the Institute’s logo. Woodhead books published in collaboration with The Textile Institute are offered to Textile Institute members at a substantial discount. These books, together with those published by The Textile Institute that are still in print, are offered on the Woodhead web site at: www.woodheadpublishing.com. Textile Institute books still in print are also available directly from the Institute’s website at: www.textileinstitutebooks.com. A list of Woodhead books on textile science and technology, most of which have been published in collaboration with The Textile Institute, can be found at the end of the contents pages. -

Development of Granulation Tissue Mimetic Scaffolds for Skin Healing

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-4-2018 12:30 PM Development Of Granulation Tissue Mimetic Scaffolds For Skin Healing Adam Hopfgartner The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Hamilton, Douglas W. The University of Western Ontario Co-Supervisor Pickering, J. Geoffrey. The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Biomedical Engineering A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Engineering Science © Adam Hopfgartner 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Biomaterials Commons, and the Molecular, Cellular, and Tissue Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Hopfgartner, Adam, "Development Of Granulation Tissue Mimetic Scaffolds For Skin Healing" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5767. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5767 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Impaired skin healing is a significant and growing clinical concern, particularly in relation to diabetes, venous insufficiency and immobility. Previously, we developed electrospun scaffolds for the delivery of periostin (POSTN) and connective tissue growth factor 2 (CCN2), matricellular proteins involved in the proliferative phase of healing. This study aimed to design and validate a novel electrosprayed coaxial microsphere for the encapsulation of fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF9), as a component of the POSTN/CCN2 scaffold, to promote angiogenic stability during wound healing. For the first time, we observed a pro-proliferative effect of FGF9 on human dermal fibroblasts (HDF) in vitro, indicating a potential cellular mechanism of action during wound healing. -

Debridement of Chronic Wounds: a Systematic Review

Health Technology Assessment 1999; Vol. 3: No. 17 (Pt 1) Review The debridement of chronic wounds: a systematic review M Bradley N Cullum T Sheldon Health Technology Assessment NHS R&D HTA Programme HTA HTA How to obtain copies of this and other HTA Programme reports. An electronic version of this publication, in Adobe Acrobat format, is available for downloading free of charge for personal use from the HTA website (http://www.hta.ac.uk). A fully searchable CD-ROM is also available (see below). Printed copies of HTA monographs cost £20 each (post and packing free in the UK) to both public and private sector purchasers from our Despatch Agents. Non-UK purchasers will have to pay a small fee for post and packing. For European countries the cost is £2 per monograph and for the rest of the world £3 per monograph. You can order HTA monographs from our Despatch Agents: – fax (with credit card or official purchase order) – post (with credit card or official purchase order or cheque) – phone during office hours (credit card only). Additionally the HTA website allows you either to pay securely by credit card or to print out your order and then post or fax it. Contact details are as follows: HTA Despatch Email: [email protected] c/o Direct Mail Works Ltd Tel: 02392 492 000 4 Oakwood Business Centre Fax: 02392 478 555 Downley, HAVANT PO9 2NP, UK Fax from outside the UK: +44 2392 478 555 NHS libraries can subscribe free of charge. Public libraries can subscribe at a very reduced cost of £100 for each volume (normally comprising 30–40 titles). -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

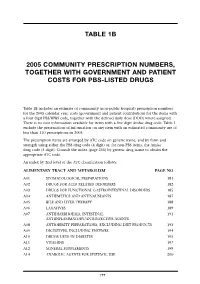

Table 1B 2005 Community Prescription Numbers, Together with Government

TABLE 1B 2005 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS-LISTED DRUGS Table 1B includes an estimate of community (non-public hospital) prescription numbers for the 2005 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 exclude the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2005. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Consult the index (page 255) by generic drug name to obtain the appropriate ATC code. An index by 2nd level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM PAGE NO A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 181 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 182 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 185 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 187 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 188 A06 LAXATIVES 189 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL 191 ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVE AGENTS A08 ANTIOBESITY PREPARATIONS, EXCLUDING DIET PRODUCTS 193 A09 DIGESTIVES, INCLUDING ENZYMES 194 A10 DRUGS USED IN DIABETES 195 A11 VITAMINS 197 A12 MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS 199 A14 ANABOLIC AGENTS FOR SYSTEMIC USE 200 177 BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS B01 ANTITHROMBOTIC AGENTS 201 B02 ANTIHAEMORRHAGICS 203 B03 -

Concentrate of Proteolytic Enzymes Enriched in Bromelain

20 September 2012 EMA/648483/2012 Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Assessment report NexoBrid Concentrate of proteolytic enzymes enriched in bromelain Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/002246 Note Assessment report as adopted by the CHMP with all information of a commercially confidential nature deleted. 7 Westferry Circus ● Canary Wharf ● London E14 4HB ● United Kingdom Telephone +44 (0)20 7418 8400 Facsimile +44 (0)20 7418 8416 E-mail [email protected] Website www.ema.europa.eu An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2012. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Table of contents 1. Background information on the procedure .............................................. 5 1.1. Submission of the dossier.................................................................................... 5 1.2. Steps taken for the assessment of the product ....................................................... 6 2. Scientific discussion ................................................................................ 7 2.1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Quality aspects .................................................................................................. 9 2.3. Non-clinical aspects .......................................................................................... 20 2.4. Clinical aspects ................................................................................................ 29 2.5. -

Pharmacy Program and Drug Formulary

Pharmacy Program and Drug Formulary Secure Horizons Group Retiree Medicare Advantage Plan n Pharmacy Program Description n Platinum Plus Enhanced Formulary California Benefits Effective January 1, 2006 Table of Contents Your Secure Horizons Group Retiree Medicare Advantage Plan Prescription Drug Benefit........................................................................................................ iii Secure Horizons Pharmacy Program Definitions .................................................................... iii What Is the Platinum Plus Enhanced Formulary? ....................................................................iv Where to Have Your Prescriptions Filled .................................................................................iv Preferred and Non-Preferred Network Pharmacies .................................................................iv Network Preferred Pharmacy Locations ..................................................................................iv How to Fill a Prescription at a Network Pharmacy ...................................................................v Mail Service Pharmacy ..............................................................................................................v Secure Horizons Group Retiree Medicare Advantage Plan Offers a Two-Part Prescription Drug Benefit ..........................................................................vii Part 1 – Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Coverage ...................................................vii How Your Medicare -

Chronic Venous Ulcers: a Comparative Effectiveness Review of Treatment Modalities Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 127

Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 127 Chronic Venous Ulcers: A Comparative Effectiveness Review of Treatment Modalities Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 127 Chronic Venous Ulcers: A Comparative Effectiveness Review of Treatment Modalities Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 540 Gaither Road Rockville, MD 20850 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. 290-2007-10061-I Prepared by: Johns Hopkins University Evidence-based Practice Center Baltimore, MD Investigators Jonathan Zenilman, M.D. M. Frances Valle, D.N.P., M.S. Mahmoud B. Malas, M.D., M.H.S. Nisa Maruthur, M.D., M.H.S. Umair Qazi, M.P.H. Yong Suh, M.B.A., M.Sc. Lisa M. Wilson, Sc.M. Elisabeth B. Haberl, B.A. Eric B. Bass, M.D., M.P.H. Gerald Lazarus, M.D. AHRQ Publication No. 13(14)-EHC121-EF December 2013 Erratum January 2014 This report is based on research conducted by the Johns Hopkins University Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) under contract to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD (Contract No. 290-2007-10061-I). The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the author(s), who are responsible for its contents; the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Therefore, no statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The information in this report is intended to help health care decisionmakers—patients and clinicians, health system leaders, and policymakers, among others—make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. -

Treatment for Acute Pain: an Evidence Map Technical Brief Number 33

Technical Brief Number 33 R Treatment for Acute Pain: An Evidence Map Technical Brief Number 33 Treatment for Acute Pain: An Evidence Map Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. 290-2015-0000-81 Prepared by: Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center Minneapolis, MN Investigators: Michelle Brasure, Ph.D., M.S.P.H., M.L.I.S. Victoria A. Nelson, M.Sc. Shellina Scheiner, PharmD, B.C.G.P. Mary L. Forte, Ph.D., D.C. Mary Butler, Ph.D., M.B.A. Sanket Nagarkar, D.D.S., M.P.H. Jayati Saha, Ph.D. Timothy J. Wilt, M.D., M.P.H. AHRQ Publication No. 19(20)-EHC022-EF October 2019 Key Messages Purpose of review The purpose of this evidence map is to provide a high-level overview of the current guidelines and systematic reviews on pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments for acute pain. We map the evidence for several acute pain conditions including postoperative pain, dental pain, neck pain, back pain, renal colic, acute migraine, and sickle cell crisis. Improved understanding of the interventions studied for each of these acute pain conditions will provide insight on which topics are ready for comprehensive comparative effectiveness review. Key messages • Few systematic reviews provide a comprehensive rigorous assessment of all potential interventions, including nondrug interventions, to treat pain attributable to each acute pain condition. Acute pain conditions that may need a comprehensive systematic review or overview of systematic reviews include postoperative postdischarge pain, acute back pain, acute neck pain, renal colic, and acute migraine. -

The Effect of Iodine Based Products on Unicellular Algae from Genus Prototheca

The Effect of Iodine Based Products on Unicellular Algae from Genus Prototheca University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, 3-5Sorin Mănăştur RĂPUNTEAN Street, *, 400372, Gheorghe Romania RĂPUNTEAN, Flore CHIRILǍ, Nicodim Iosif FIŢ, George Cosmin NADǍŞ *Corresponding author: [email protected] Bulletin UASVM Veterinary Medicine 72(2) / 2015, Print ISSN 1843-5270; Electronic ISSN 1843-5378 DOI:10.15835/buasvmcn-vm: 11439 Abstract Iodine based products have been and are still used in medicine as disinfectant or antiseptic substances, because of their bactericidal, sporicidal, protocidal and disinfection effect. Algaecide effect has been lessPrototheca studied and represents a strong motivation for this study. This paper is aiming to test the sensitivityPrototheca to zopfii iodine based products of unicellular algae of the genus . Such products might be used for the treatment of diseases involving these pathogens. A total number of twenty-two strains isolated from cows with mastitis or bovine shelters, Protothecawere tested wickerhamii within this study. The algal strains were identified based on morphological characteristics (shape, size, presence of endospores), cultural (liquid and solid media characteristics) and biochemical (fermentation of sugars). ATCC 16529 reference strain was also included in the evaluation. Iodinated products used were represented by: Lugol solution, iodine tincture, betadine, videne and potassium iodide. Determination of the inhibitory effect was measured by diffusion technique in agarose gel and by liquid medium dilution method. For the tincture of iodine and betadine, the inhibitory effect was also appreciated in relation with the time of contact (5, 10, 15, 30 and 60 minutes). Prototheca zopfii By the agar diffusion technique, it was found that inhibition zones varying sizes were correlated with the composition of those products.