Chronic Venous Ulcers: a Comparative Effectiveness Review of Treatment Modalities Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 127

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antiseptics and Disinfectants for the Treatment Of

Verstraelen et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2012, 12:148 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/12/148 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Antiseptics and disinfectants for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis: A systematic review Hans Verstraelen1*, Rita Verhelst2, Kristien Roelens1 and Marleen Temmerman1,2 Abstract Background: The study objective was to assess the available data on efficacy and tolerability of antiseptics and disinfectants in treating bacterial vaginosis (BV). Methods: A systematic search was conducted by consulting PubMed (1966-2010), CINAHL (1982-2010), IPA (1970- 2010), and the Cochrane CENTRAL databases. Clinical trials were searched for by the generic names of all antiseptics and disinfectants listed in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System under the code D08A. Clinical trials were considered eligible if the efficacy of antiseptics and disinfectants in the treatment of BV was assessed in comparison to placebo or standard antibiotic treatment with metronidazole or clindamycin and if diagnosis of BV relied on standard criteria such as Amsel’s and Nugent’s criteria. Results: A total of 262 articles were found, of which 15 reports on clinical trials were assessed. Of these, four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were withheld from analysis. Reasons for exclusion were primarily the lack of standard criteria to diagnose BV or to assess cure, and control treatment not involving placebo or standard antibiotic treatment. Risk of bias for the included studies was assessed with the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. Three studies showed non-inferiority of chlorhexidine and polyhexamethylene biguanide compared to metronidazole or clindamycin. One RCT found that a single vaginal douche with hydrogen peroxide was slightly, though significantly less effective than a single oral dose of metronidazole. -

Wound Bed Preparation: TIME in Practice

Clinical PRACTICE DEVELOPMENT Wound bed preparation: TIME in practice Wound bed preparation is now a well established concept and the TIME framework has been developed as a practical tool to assist practitioners when assessing and managing patients with wounds. It is important, however, to remember to assess the whole patient; the wound bed preparation ‘care cycle’ promotes the treatment of the ‘whole’ patient and not just the ‘hole’ in the patient. This paper discusses the implementation of the wound bed preparation care cycle and the TIME framework, with a detailed focus on Tissue, Infection, Moisture and wound Edge (TIME). Caroline Dowsett, Heather Newton dependent on one another. Acute et al, 2003). Wound bed preparation wounds usually follow a well-defined as a concept allows the clinician to KEY WORDS process described as: focus systematically on all of the critical Wound bed preparation 8Coagulation components of a non-healing wound to Tissue 8Inflammation identify the cause of the problem, and Infection 8Cell proliferation and repair of implement a care programme so as to Moisture the matrix achieve a stable wound that has healthy 8Epithelialisation and remodelling of granulation tissue and a well vascularised Edge scar tissue. wound bed. In the past this model of healing has The TIME framework been applied to chronic wounds, but To assist with implementing the he concept of wound bed it is now known that chronic wound concept of wound bed preparation, the preparation has gained healing is different from acute wound TIME acronym was developed in 2002 T international recognition healing. Chronic wounds become ‘stuck’ by a group of wound care experts, as a framework that can provide in the inflammatory and proliferative as a practical guide for use when a structured approach to wound stages of healing (Ennis and Menses, managing patients with wounds (Schultz management. -

Effect of Polyhexamethylene Biguanide in Combination with Undecylenamidopropyl Betaine Or Pslg on Biofilm Clearance

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Effect of Polyhexamethylene Biguanide in Combination with Undecylenamidopropyl Betaine or PslG on Biofilm Clearance Yaqian Zheng 1,2,†, Di Wang 1,† and Luyan Z. Ma 1,3,* 1 State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (D.W.) 2 College of Life Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 Savaid Medical School, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-64807437 † These authors have contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Hospital-acquired infection is a great challenge for clinical treatment due to pathogens’ biofilm formation and their antibiotic resistance. Here, we investigate the effect of antiseptic agent polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) and undecylenamidopropyl betaine (UB) against biofilms of four pathogens that are often found in hospitals, including Gram-negative bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli, Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus, and pathogenic fungus, Candida albicans. We show that 0.02% PHMB, which is 10-fold lower than the concentration of commercial products, has a strong inhibitory effect on the growth, initial attachment, and biofilm formation of all tested pathogens. PHMB can also disrupt the preformed biofilms of these pathogens. In contrast, 0.1% UB exhibits a mild inhibitory effect on biofilm formation of the four pathogens. This concentration inhibits the growth of S. aureus and C. albicans yet has no growth effect on P. aeruginosa or E. coli. UB only slightly enhances the anti-biofilm efficacy of PHMB on P. -

Understand Your Chronic Wound

Patient Information Leaflet Understanding your Chronic Wound Dressings, management and wound infection In this leaflet Health Care Professional (HCP) refers to any member of the team involved in your wound care. This can include treatment room or practice nurse, community, ward or clinic nurse, GP or hospital doctor, podiatrist etc. Chronic Wounds and Dressings What is a Chronic wound? A wound with slow progress towards healing or shows delayed healing. This may be due to underlying issues such as: • Poor blood flow and less oxygen getting to the wound • Other health conditions • Poor diet, smoking, pressure on the wound e.g. footwear/seating. Can my wound be left open to the air? No, the evidence shows that wounds heal better when the surface is kept moist (not too wet or dry). The moisture provides the correct environment to aid your wound to heal. Does my dressing need changed daily? Not usually, your HCP will explain how often it needs changed. This will depend on the level of fluid leaking from your wound. Some dressings can be left in place up to a week. Most wounds have a slight odour, but if a wound smells bad it could be a sign that something is wrong. See section on wound infection. Your dressing may indicate that it needs changed when the dark area in the centre gets close to the edge of the dressing pad. The dark area is fluid from your wound, this is normal. It will be dry to touch. Let your HCP know if your dressing needs changed before your next visit or appointment is due. -

Guideline: Wound Bed Preparation for Healable and Non Healable Wounds

British Columbia Provincial Nursing Skin and Wound Committee Guideline: Wound Bed Preparation for Healable and Non Healable Wounds Developed by the BC Provincial Nursing Skin and Wound Committee in collaboration with Wound Clinicians from: / TITLE Guideline: Wound Bed Preparation for Healable and Non-Healable Wounds in Adults & Children1 Practice Level Nurses in accordance with health authority and agency policy. Conservative sharp wound debridement (CSWD) is a restricted activity according to the Nurse’s (Registered) and Nurse Practitioner Regulation. 2 CRNBC states that registered nurses must successfully complete additional education and follow an established guideline when carrying out CSWD. Biological debridement therapy is a restricted activity according to the Nurse’s (Registered) and Nurse Practitioner Regulation. 3 CRNBC states that registered nurses must follow an established guideline when carrying out biological debridement. Clients 4 with wounds needing wound bed preparation require an interprofessional approach to provide comprehensive, evidence-based assessment and treatment. This clinical practice guideline focuses solely on the role of the nurse, as one member of the interprofessional team providing care to these clients. Background Factors affecting wound healability include the presence of adequate circulation in the area of the wound, wound related factors such as the size and duration of the wound, the ability to treat the cause of the wound and the presence of risk factors impacting wound healing. While many wounds heal, others are determined to be non-healing or slow-to-heal based on the presence or absence of these factors. Wound healability must be determined prior to debridement and moist wound healing. Although wound healing normally occurs in a predictable fashion, wound healing trajectories can be heterogeneous and non- uniform resulting is delayed wound healing for some clients. -

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

EuropeanN Bryan etCells al. and Materials Vol. 24 2012 (pages 249-265) Reactive DOI: 10.22203/eCM.v024a18oxygen species in inflammation and ISSN wound 1473-2262 healing REACTIVE OXYGEN SPECIES (ROS) – A FAMILY OF FATE DECIDING MOLECULES PIVOTAL IN CONSTRUCTIVE INFLAMMATION AND WOUND HEALING Nicholas Bryan1*, Helen Ahswin2, Neil Smart3, Yves Bayon2, Stephen Wohlert2 and John A. Hunt1 1Clinical Engineering, UKCTE, UKBioTEC, The Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease, University of Liverpool, Duncan Building, Daulby Street, Liverpool, L69 3GA, UK 2Covidien – Sofradim Production, 116 Avenue du Formans – BP132, F-01600 Trevoux, France 3Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital, Barrack Road, Exeter, Devon, EX2 5DW, UK Abstract Introduction Wound healing requires a fine balance between the positive The survival and longevity of any animal requires an active and deleterious effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS); vigilant set of defence mechanisms to combat infection, a group of extremely potent molecules, rate limiting in efficiently repair damaged tissue and remove debris successful tissue regeneration. A balanced ROS response associated with apoptotic/necrotic cells. Compromised will debride and disinfect a tissue and stimulate healthy tissue rapidly results in decreased mobility, organ failures, tissue turnover; suppressed ROS will result in infection hypovolaemia, hypermetabolism, and ultimately infection and an elevation in ROS will destroy otherwise healthy and sepsis. Therefore, mammals have evolved an array stromal tissue. Understanding and anticipating the ROS of physiological pathways and mechanisms that enable niche within a tissue will greatly enhance the potential to damaged tissue to return to a basal homeostatic state. In exogenously augment and manipulate healing. an ideal scenario this occurs without compromise of tissue Tissue engineering solutions to augment successful mechanics, scarring or incorporation of microbial material. -

The Role of Antioxidants on Wound Healing: a Review of the Current Evidence

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 15 July 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202107.0361.v1 Review THE ROLE OF ANTIOXIDANTS ON WOUND HEALING: A REVIEW OF THE CURRENT EVIDENCE. Inés María Comino-Sanz 1*, María Dolores López-Franco1, Begoña Castro2, Pedro Luis Pancorbo-Hidalgo1 1 Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Jaén, 23071 Jaén (Spain); [email protected] (IMCS); MDLP ([email protected]); PLPH ([email protected]). 2 Histocell S.L., Bizkaia Science and Technology Park, Derio, Bizkaia (Spain); [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-953213627 Abstract: (1) Background: Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a crucial role in the preparation of the normal wound healing response. Therefore, a correct balance between low or high levels of ROS is essential. Antioxidant dressings that regulate this balance is a target for new therapies. The pur- pose of this review is to identify the compounds with antioxidant properties that have been tested for wound healing and to summarize the available evidence on their effects. (2) Methods: A litera- ture search was conducted and included any study that evaluated the effects or mechanisms of an- tioxidants in the healing process (in vitro, animal models, or human studies). (3) Results: Seven compounds with antioxidant activity were identified (Curcumin, N-acetyl cysteine, Chitosan, Gallic Acid, Edaravone, Crocin, Safranal, and Quercetin) and 46 studies reporting the effects on the healing process of these antioxidants compounds were included. (4) Conclusions: These results highlight that numerous novel investigations are being conducted to develop more efficient systems for wound healing activity. The application of antioxidants is useful against oxidative damage and ac- celerates wound healing. -

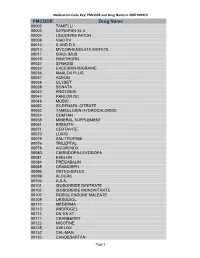

Medication Code Key: PMCODE and Drug Name in 2007 NHHCS Cdc-Pdf

Medication Code Key: PMCODE and Drug Name in 2007 NHHCS PMCODE Drug Name 00002 TAMIFLU 00003 DITROPAN XL II 00004 LIDODERM PATCH 00008 VIACTIV 00010 A AND D II 00013 MYCOPHENOLATE MOFETIL 00017 SIROLIMUS 00019 HAWTHORN 00027 SYNAGIS 00032 EXCEDRIN MIGRAINE 00036 MAALOX PLUS 00037 ACEON 00038 GLYSET 00039 SONATA 00042 PROTONIX 00044 PANLOR DC 00048 MOBIC 00052 SILDENAFIL CITRATE 00053 TAMSULOSIN HYDROCHLORIDE 00054 COMTAN 00058 MINERAL SUPPLEMENT 00061 BISMUTH 00071 CERTAVITE 00073 LUXIQ 00075 SAL-TROPINE 00076 TRILEPTAL 00078 AGGRENOX 00080 CARBIDOPA-LEVODOPA 00081 EXELON 00084 PREGABALIN 00085 ORAMORPH 00096 OSTEO-BIFLEX 00099 ALOCRIL 00100 A.S.A. 00101 ISOSORBIDE DINITRATE 00102 ISOSORBIDE MONONITRATE 00107 ROSIGLITAZONE MALEATE 00109 URSODIOL 00112 MEDERMA 00113 ANDROGEL 00114 DILTIA XT 00117 CRANBERRY 00123 NICOTINE 00125 AVELOX 00132 CAL-MAG 00133 CANDESARTAN Page 1 Medication Code Key: PMCODE and Drug Name in 2007 NHHCS PMCODE Drug Name 00148 PROLIXIN D 00149 D51/2 NS 00150 NICODERM CQ PATCH 00151 TUSSIN 00152 CEREZYME 00154 CHILDREN'S IBUPROFEN 00156 PROPOXACET-N 00159 KALETRA 00161 BISOPROLOL 00167 NOVOLIN N 00169 KETOROLAC TROMETHAMINE 00172 OPHTHALMIC OINTMENT 00173 ELA-MAX 00176 PREDNISOLONE ACETATE 00179 COLLOID SILVER 00184 KEPPRA 00187 OPHTHALMIC DROPS 00190 ABDEC 00191 HAPONAL 00192 SPECTRAVITE 00198 ENOXAPARIN SODIUM 00206 ACTONEL 00208 CELECOXIB 00209 GLUCOVANCE 00211 LEVALL 5.0 00213 PANTOPRAZOLE SODIUM 00217 TEMODAR 00218 CARBAMIDE PEROXIDE 00221 CHINESE HERBAL MEDS 00224 MILK AND MOLASSES ENEMA 00238 ZOLMITRIPTAN 00239 -

Advanced Textiles for Wound Care

Woodhead Publishing in Textiles: Number 85 Advanced textiles for wound care Edited by S. Rajendran Oxford Cambridge New Delhi © 2009 Woodhead Publishing Limited The Textile Institute and Woodhead Publishing The Textile Institute is a unique organisation in textiles, clothing and footwear. Incorporated in England by a Royal Charter granted in 1925, the Institute has individual and corporate members in over 90 countries. The aim of the Institute is to facilitate learning, recognise achievement, reward excellence and disseminate information within the global textiles, clothing and footwear industries. Historically, The Textile Institute has published books of interest to its members and the textile industry. To maintain this policy, the Institute has entered into partnership with Woodhead Publishing Limited to ensure that Institute members and the textile industry continue to have access to high calibre titles on textile science and technology. Most Woodhead titles on textiles are now published in collaboration with The Textile Institute. Through this arrangement, the Institute provides an Editorial Board which advises Woodhead on appropriate titles for future publication and suggests possible editors and authors for these books. Each book published under this arrangement carries the Institute’s logo. Woodhead books published in collaboration with The Textile Institute are offered to Textile Institute members at a substantial discount. These books, together with those published by The Textile Institute that are still in print, are offered on the Woodhead web site at: www.woodheadpublishing.com. Textile Institute books still in print are also available directly from the Institute’s website at: www.textileinstitutebooks.com. A list of Woodhead books on textile science and technology, most of which have been published in collaboration with The Textile Institute, can be found at the end of the contents pages. -

Association Between Hemorrhoids and Lower Extremity Chronic Venous Insufficiency

Open Access Original Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.4502 Association Between Hemorrhoids and Lower Extremity Chronic Venous Insufficiency Ugur Ekici 1 , Abdulcabbar Kartal 2 , Murat F. Ferhatoglu 2 1. General Surgery, Istanbul Gelişim University, Istanbul, TUR 2. General Surgery, Okan University Medical Faculty, Istanbul, TUR Corresponding author: Abdulcabbar Kartal, [email protected] Disclosures can be found in Additional Information at the end of the article Abstract Aim The aim of the present study was to evaluate the incidence of varicose veins among patients with hemorrhoidal disease and to compare its incidence reported in various community-based studies. Method The study group comprised of 100 patients who underwent surgery for symptomatic internal or external hemorrhoids; the control group consisted of 100 volunteers who received no prior therapy for hemorrhoidal disease and lacked any symptoms or findings suggestive of this condition. Subjects in both the groups were inquired with respect to their demographic data and risk factors. Both groups were asked to stand for two minutes before performing leg examinations while still in the standing position. The findings were recorded for both the groups. Varicose veins were classified according to the clinical appearance section of the Clinical, Etiologic, Anatomic, and Pathophysiologic (CEAP) classification that was developed by the 1994 American Venous Forum. Results There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to age and body mass index (BMI). Significant relationships were identified between the groups with respect to the incidence of varicose veins and chronic constipation. The incidence of C1 and C2 varicose veins observed in the study group was higher than that observed in the control group. -

Original Article

Original Article Is chronic venous ulcer curable? A sample survey of a plastic surgeon V. Alamelu Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Faciomaxillary Surgery, Madras Medical College and Govt General Hospital, Chennai - 600 003; Sri Jayam Hospital, West Tambaram, Chennai - 600 045; K.J. Hospital and Research Foundation, Poonamallee High Road, Chennai - 600 084, India Address for correspondence: Dr. V. Alamelu, 23, Ramakrishnan Street, West Tambaram, Chennai-600 045, India. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Introduction: Venous ulcers of lower limbs are often chronic and non-healing, many a time neglected by patients and their treating physicians as these ulcers mostly do not lead to amputation as in gangrenous arterial ulcer and also cost much to complete the course of treatment and prevention of recurrence. Materials and Methods: One hundred and twenty two lower limb venous ulcers came up for treatment between May 2006 and April 2009. Only twenty nine cases completed the treatment. The main tool of investigation was the non invasive Duplex scan venography. Biopsy of the ulcer was done for staging the disease. Patients’ choice of treatment was always conservative and as out-patient instead of hospitalisation and surgery, which required a lot of motivation by the treating unit. Results: Out of twenty nine cases, ten cases were treated conservatively and seven (24.13%) healed well. Remaining nineteen cases were given surgical modality in which fifteen cases (51.74%) were successful. Only seven cases (24.13%) failed to heal. Compression stockings were advised to control oedema, varices and pain. Foot care, regular exercises and follow-up were stressed effectively. -

Debridement of Chronic Wounds: a Systematic Review

Health Technology Assessment 1999; Vol. 3: No. 17 (Pt 1) Review The debridement of chronic wounds: a systematic review M Bradley N Cullum T Sheldon Health Technology Assessment NHS R&D HTA Programme HTA HTA How to obtain copies of this and other HTA Programme reports. An electronic version of this publication, in Adobe Acrobat format, is available for downloading free of charge for personal use from the HTA website (http://www.hta.ac.uk). A fully searchable CD-ROM is also available (see below). Printed copies of HTA monographs cost £20 each (post and packing free in the UK) to both public and private sector purchasers from our Despatch Agents. Non-UK purchasers will have to pay a small fee for post and packing. For European countries the cost is £2 per monograph and for the rest of the world £3 per monograph. You can order HTA monographs from our Despatch Agents: – fax (with credit card or official purchase order) – post (with credit card or official purchase order or cheque) – phone during office hours (credit card only). Additionally the HTA website allows you either to pay securely by credit card or to print out your order and then post or fax it. Contact details are as follows: HTA Despatch Email: [email protected] c/o Direct Mail Works Ltd Tel: 02392 492 000 4 Oakwood Business Centre Fax: 02392 478 555 Downley, HAVANT PO9 2NP, UK Fax from outside the UK: +44 2392 478 555 NHS libraries can subscribe free of charge. Public libraries can subscribe at a very reduced cost of £100 for each volume (normally comprising 30–40 titles).