La Règle “JOMINI”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The La Solidaridad and Philippine Journalism in Spain (1889-1895)

44 “Our Little Newspaper”… “OUR LITTLE NEWSPAPER” THE LA SOLIDARIDAD AND PHILIPPINE JOURNALISM IN SPAIN (1889-1895) Jose Victor Z. Torres, PhD De La Salle University-Manila [email protected] “Nuestros periodiquito” or “Our little newspaper” Historian, archivist, and writer Manuel Artigas y was how Marcelo del Pilar described the periodical Cuerva had written works on Philippine journalism, that would serve as the organ of the Philippine especially during the celebration of the tercentenary reform movement in Spain. For the next seven years, of printing in 1911. A meticulous researcher, Artigas the La Solidaridad became the respected Philippine newspaper in the peninsula that voiced out the viewed and made notes on the pre-war newspaper reformists’ demands and showed their attempt to collection in the government archives and the open the eyes of the Spaniards to what was National Library. One of the bibliographical entries happening to the colony in the Philippines. he wrote was that of the La Solidaridad, which he included in his work “El Centenario de la Imprenta”, But, despite its place in our history, the story of a series of articles in the American period magazine the La Solidaridad has not entirely been told. Madalas Renacimiento Filipino which ran from 1911-1913. pag-usapan pero hindi alam ang kasaysayan. We do not know much of the La Solidaridad’s beginnings, its Here he cited a published autobiography by reformist struggle to survive as a publication, and its sad turned revolutionary supporter, Timoteo Paez as his ending. To add to the lacunae of information, there source. -

V49 No 1 2013

1 Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia Vinod Raina (1950–2013) Eduardo C. TADEM and Katrina S. NAVALLO Introduction Eduardo C. TADEM and Janus Isaac V. NOLASCO ARTICLES From Cádiz to La Liga: The Spanish Context of Rizal’s Political Thought George ASENIERO Rural China: From Modernization to Reconstruction Tsui SIT and Tak Hing WONG A Preliminary Study of Ceiling Murals from Five Southeastern Cebu Churches Reuben Ramas CAÑETE Bayan Nila: Pilipino Culture Nights and Student Performance at Home in Southern California Neal MATHERNE COMMENTARIES Identity Politics in the Developmentalist States of East Asia: The Role of Diaspora Communities in the Growth of Civil Societies Kinhide MUSHAKOJI La Liga in Rizal Scholarship George ASENIERO Influence of Political Parties on the Judicial Process in Nepal Md. Nurul MOMEN REVIEWS LITERARY WRITINGS Thomas David CHAVES Celine SOCRATES Volume V4olume9 Number 49:1 (2013) 1 2013 2 ASIAN STUDIES is an open-access, peer-reviewed academic journal published since 1963 by the Asian Center, University of the Philippines Diliman. EDITORIAL BOARD* • Eduardo C. Tadem (Editor in Chief), Asian Studies • Michiyo Yoneno-Reyes (Book Review editor), Asian Studies • Eduardo T. Gonzalez, Asian and Philippine Studies • Ricardo T. Jose, History • Joseph Anthony Lim, Economics • Antoinette R. Raquiza, Asian Studies • Teresa Encarnacion Tadem, Political Science • Lily Rose Tope, English and Comparative Literature *The members of the Editorial Board are all from the University of the Philippines Diliman EDITORIAL STAFF • Janus Isaac V. Nolasco, Managing Editor • Katrina S. Navallo, Editorial Associate • Ariel G. Manuel, Layout Artist EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD • Patricio N. Abinales, University of Hawaii at Manoa • Andrew Charles Bernard Aeria, University of Malaysia Sarawak • Benedict Anderson, Cornell University • Melani Budianta, University of Indonesia • Urvashi Butalia, Zubaan Books (An imprint of Kali for Women) • Vedi Renandi Hadiz, Murdoch University • Caroline S. -

China on the Sea China Studies

China on the Sea China Studies Editors Glen Dudbridge Frank Pieke VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at www.brill.com/chs China on the Sea How the Maritime World Shaped Modern China By Zheng Yangwen 鄭揚文 LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 Cover caption: The several known complete sets of “Copper engravings of the European palaces in Yuan Ming Yuan” [圆明园西洋楼铜板画] each include 20 images. However, the set belonging to the John Rylands Library, University of Manchester, was recently found to include a unique additional colour image. Jottings at the top and bottom read: “Planche 2e qui a été commencée à être mise en couleurs” and “Planche 2e esquissée pour la couleur”. Reproduced by courtesy of the University Librarian and Director, the John Rylands University Library, University of Manchester. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zheng, Yangwen. China on the sea / by Zheng Yangwen. p. cm. — (China studies ; v. 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-19477-9 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. China—Commerce—Foreign countries. 2. China—Foreign economic relations—History. 3. China—History—Qing dynasty, 1644–1912. 4. China—Merchant marine—History. I. Title. HF3834.Z476 2011 387.50951’0903—dc23 2011034522 ISSN 1570-1344 ISBN 978 90 04 28160 8 (paperback) ISBN 978 90 04 19478 6 (e-book) This paperback was originally published in hardback under ISBN 978-90-04-19477-9. Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. -

Nytårsrejsen Til Filippinerne – 2014

Nytårsrejsen til Filippinerne – 2014. Martins Dagbog Dorte og Michael kørte os til Kastrup, og det lykkedes os at få en opgradering til business class - et gammelt tilgodebevis fra lidt lægearbejde på et Singapore Airlines fly. Vi fik hilst på vore 16 glade gamle rejsevenner ved gaten. Karin fik lov at sidde på business class, mens jeg sad på det sidste sæde i økonomiklassen. Vi fik julemad i flyet - flæskesteg med rødkål efterfulgt af ris á la mande. Serveringen var ganske god, og underholdningen var også fin - jeg så filmen "The Hundred Foot Journey", som handlede om en indisk familie, der åbner en restaurant lige overfor en Michelin-restaurant i en mindre fransk by - meget stemningsfuld og sympatisk. Den var instrueret af Lasse Hallström. Det tog 12 timer at flyve til Singapore, og flyet var helt fuldt. Flytiden mellem Singapore og Manila var 3 timer. Vi havde kun 30 kg bagage med tilsammen (12 kg håndbagage og 18 kg i en indchecket kuffert). Jeg sad ved siden af en australsk student, der skulle hjem til Perth efter et halvt år i Bergen. Hans fly fra Lufthansa var blevet aflyst, så han havde måttet vente 16 timer i Københavns lufthavn uden kompensation. Et fly fra Air Asia på vej mod Singapore forulykkede med 162 personer pga. dårligt vejr. Miriams kuffert var ikke med til Manilla, så der måtte skrives anmeldelse - hun fik 2200 pesos til akutte fornødenheder. Vi vekslede penge som en samlet gruppe for at spare tid og gebyr - en $ var ca. 45 pesos. Vi kom i 3 minibusser ind til Manila Hotel, hvor det tog 1,5 time at checke os ind på 8 værelser. -

The Philippines

WORKING PAPERS OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS COMPARATIVE NONPROFIT SECTOR PROJECT Lester M. Salamon Director Defining the Nonprofit Sector: The Philippines Ledivina V. Cariño and the PNSP Project Staff 2001 Ugnayan ng Pahinungod (Oblation Corps) University of the Philippines Suggested form of citation: Cariño, Ledivina V. and the PNSP Project Staff. “Volunteering in Cross-National Perspective: Evidence From 24 Countries.” Working Papers of the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project, no. 39. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies, 2001. ISBN 1-886333-46-7 © The Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies, 2001 All rights reserved Center for Civil Society Studies Institute for Policy Studies The Johns Hopkins University 3400 N. Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-2688 USA Institute for Policy Studies Wyman Park Building / 3400 North Charles Street / Baltimore, MD 21218-2688 410-516-7174 / FAX 410-516-8233 / E-mail: [email protected] Center for Civil Society Studies Preface This is one in a series of working papers produced under the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project (CNP), a collaborative effort by scholars around the world to understand the scope, structure, and role of the nonprofit sector using a common framework and approach. Begun in 1989 in 13 countries, the Project continues to expand, currently encompassing about 40 countries. The working papers provide a vehicle for the initial dissemination of the work of the Project to an international audience of scholars, practitioners and policy analysts interested in the social and economic role played by nonprofit organizations in different countries, and in the comparative analysis of these important, but often neglected, institutions. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Language, Tagalog Regionalism, and Filipino Nationalism: How a Language-Centered Tagalog Regionalism Helped to Develop a Philippine Nationalism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/69j3t8mk Author Porter, Christopher James Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Language, Tagalog Regionalism, and Filipino Nationalism: How a Language-Centered Tagalog Regionalism Helped to Develop a Philippine Nationalism A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Southeast Asian Studies by Christopher James Porter June 2017 Thesis Committee: Dr. Hendrik Maier, Chairperson Dr. Sarita See Dr. David Biggs Copyright by Christopher James Porter 2017 The Thesis of Christopher James Porter is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Table of Contents: Introduction………………………………………………….. 1-4 Part I: Filipino Nationalism Introduction…………………………………………… 5-8 Spanish Period………………………………………… 9-21 American Period……………………………………… 21-28 1941 to Present……………………………………….. 28-32 Part II: Language Introduction…………………………………………… 34-36 Spanish Period……………………………………….... 36-39 American Period………………………………………. 39-43 1941 to Present………………………………………... 44-51 Part III: Formal Education Introduction…………………………………………… 52-53 Spanish Period………………………………………… 53-55 American Period………………………………………. 55-59 1941 to 2009………………………………………….. 59-63 A New Language Policy……………………………… 64-68 Conclusion……………………………………………………. 69-72 Epilogue………………………………………………………. 73-74 Bibliography………………………………………………….. 75-79 iv INTRODUCTION: The nation-state of the Philippines is comprised of thousands of islands and over a hundred distinct languages, as well as over a thousand dialects of those languages. The archipelago has more than a dozen regional languages, which are recognized as the lingua franca of these different regions. -

Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914

Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 by M. Carmella Cadusale Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2016 Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 M. Carmella Cadusale I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: M. Carmella Cadusale, Student Date Approvals: Dr. L. Diane Barnes, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. David Simonelli, Committee Member Date Dr. Helene Sinnreich, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT Filipino culture was founded through the amalgamation of many ethnic and cultural influences, such as centuries of Spanish colonization and the immigration of surrounding Asiatic groups as well as the long nineteenth century’s Race of Nations. However, the events of 1898 to 1914 brought a sense of national unity throughout the seven thousand islands that made the Philippine archipelago. The Philippine-American War followed by United States occupation, with the massive domestic support on the ideals of Manifest Destiny, introduced the notion of distinct racial ethnicities and cemented the birth of one national Philippine identity. The exploration on the Philippine American War and United States occupation resulted in distinguishing the three different analyses of identity each influenced by events from 1898 to 1914: 1) The identity of Filipinos through the eyes of U.S., an orientalist study of the “us” versus “them” heavily influenced by U.S. -

Las Fuerzas De Sus Reinos.Int.Indd 1 3/31/17 12:12 PM Las Fuerzas De Sus Reinos.Int.Indd 2 3/31/17 12:12 PM EDER ANTONIO DE JESÚS GALLEGOS RUIZ

Las fuerzas de sus reinos.int.indd 1 3/31/17 12:12 PM Las fuerzas de sus reinos.int.indd 2 3/31/17 12:12 PM EDER ANTONIO DE JESÚS GALLEGOS RUIZ FUERZAS DE SUS REINOS Instrumentos de la guerra en la frontera oceánica del Pacífico hispano (1571-1698) COLECCIÓN “EL PACÍFICO, UN MAR DE HISTORIA” “Divulguemos la Historia para mejorar la sociedad” Las fuerzas de sus reinos.int.indd 3 3/31/17 12:12 PM COLECCIÓN: “EL PACÍFICO, UN MAR DE HISTORIA” comité editorial Lothar Knauth Luis Abraham Barandica José Luis Chong asesor editorial Ricardo Martínez (Universidad de Costa Rica) consejo científico Flora Botton (El Colegio de México) David Kentley (Elizabethtown College) Eduardo Madrigal (Universidad de Costa Rica) Manel Ollé (Universidad Pompeu Fabra) Edward Slack Jr. (Eastern Washington University) Carmen Yuste (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) Cuidado de la edición: Víctor Cuchí Diseño de cubierta: Patricia Pérez Ramírez Imágenes de portada: Cañón "El Cantero", colección del Museo Histórico Militar de Sevilla. Imagen autorizada por la Subdirección de Patrimonio Histórico Cultural. Instituto de Historia y Cultura Militar. Ministerio de Defensa de España. Detalle de Carta Náutica de 1622, Hessel Gerritsz. Biblioteca Nacional de Francia. Primera edición: octubre de 2015 D.R. © Palabra de Clío, A. C. 2007 Insurgentes Sur # 1814-101. Colonia Florida. C.P. 01030 Mexico, D.F. Colección "El Pacífico, un mar de Historia" ISBN: 978-607-97048-1-0 Volumen 2 “Fuerzas de sus reinos” ISBN: 978-607-97546-0-0 Impreso y hecho en México www.palabradeclio.com.mx Las fuerzas de sus reinos.int.indd 4 3/31/17 12:12 PM Índice Agradecimientos . -

Manila Y La Empresa Imperial Del Sultanato De Brunéi En El Siglo XVI

Cuaderno Internacional de Estudios Humanísticos y Literatura: CIEHL Vol. 20: 2013 Manila y la empresa imperial del Sultanato de Brunéi en el siglo XVI Isaac Donoso Universidad de Alicante I. LA EXPANSIÓN TALASOCRÁTICA DEL SULTANATO DE BRUNÉI Tradicionalmente se ha considerado el Sultanato de Brunéi uno de los más antiguos del mundo insular del Sudeste Asiático. Sin embargo, no se sabe con certeza la fecha en que se funda. Las noticias ciertas son que para la primera parte del siglo XVI, el gobernador local adopta el Islam como religión oficial y se proclama sultán: “Some time between January 1514 and December 1515, the King or Maharaja of Brunei embraced Islam and became the first sultan, Sultan Muhammad”1. Si anteriormente algún otro reyezuelo se pudiera haber proclamado sultán, no hay datos que lo aseveren. Consecuentemente, no se pueda certificar que el Sultanato de Brunéi alcance mediados del siglo XV como se estipula para el caso del Sultanato de Sulú en el Archipiélago Filipino2. No obstante, e independientemente de qué sultanato es anterior (ocupando por lo tanto la mayor antigüedad en el mundo oriental del Sudeste Asiático), lo cierto es que población musulmana debió de ser especialmente activa en Brunéi. Si bien la asunción del título de sultán pudiera retrasarse, no hay duda de la capacidad islámica e islamizadora de Brunéi para mediados del siglo XV. En efecto, de forma entusiasta se califica como “Imperio de Brunéi” al gobierno del quinto Aunque ciertamente los límites son exagerados en lo .(1524-1485) السلطان البلقية / sultán, Sultán Bulqya concerniente a expansión territorial, sí es cierto que con las reglas del juego de la política en el Sudeste Asiático ―la talasocracia―, Brunéi alcanzó una preeminencia significativa a comienzos del siglo XVI: “The fifth sultan, Bolkiah, has entered Brunei legend as Nakhuda Ragam, the Singing Admiral […], whose reign saw the expansion of Brunei to its greatest extend: the re- establishment for the third time of that thalassocracy which embraced the trading ports of Borneo, Sulu, and the Philippines”3. -

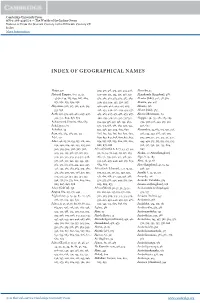

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

What Are Reflected by the Navigations of Zheng He and Christopher Columbus

International Relations and Diplomacy, February 2018, Vol. 6, No. 02, 110-121 doi: 10.17265/2328-2134/2018.02.005 D D AV I D PUBLISHING What are Reflected by the Navigations of Zheng He and Christopher Columbus WANG Min-qin Hunan University, Changsha, China The contrast of the navigations of Zheng He and Christopher Columbus shows two kinds of humanistic values: harmonious altruism reflected by Chinese culture and aggressive egocentrism revealed by the Western culture and their different effects on the world. This article explores the reasons for their different actions, trying to demonstrate that Western humanistic education is problematic. Keywords: Western culture, Chinese culture, humanism, values Introduction There were a lot of articles and books discussing about Zheng He and Christopher Columbus separately. Columbus’s studies paid more attention to Columbus’s voyages and their impact to local people. The Tainos: Rise & Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus edited by Irving Rouse (1992) was a temperate and balanced description. Samuel M. Wilson (1990) illustrated the character and destruction of Taino culture in Hispaniola: Caribbean Chiefdoms in the Age of Columbus. The effect of the first encounters on the native populations was given by James Axtell (1992) in Beyond 1492: Encounters in Colonial North America. The debate over Columbus’s achievements was presented in Secret Judgments of God: Old World Disease in Colonial Spanish America edited by Noble David Cook and W. George Lovell (1991) on the disastrous effects on the native peoples. An anti-European treatment was shown in Ray González’s (1992) Without Discovery: A Native Response to Columbus (Flint, 2014). -

La Liga in Rizal Scholarship

149 La Liga in Rizal Scholarship George ASENIERO Independent Scholar THE VAST AND CONTINUALLY growing body of Rizal studies has surprisingly paid little attention to the Statutes of La Liga Filipina. Most commentators are drawn to the fifth aim— study and application of reforms—and conclude that La Liga was Rizal’s last vain effort at reformist politics, which was cut short by his sudden deportation to Dapitan and replaced by Bonifacio’s revolutionary organization, the Katipunan. The document itself is hard to find, as it appears only in varying brevity in a few compilations. Remarkably, even the official edition of Rizal’s complete works published by the Centennial Commission in 1961 included only the abridged version by Wenceslao Retana. Thankfully, this serious omission in historiography has been redressed in the digital age with the online publication of the original text by Project Gutenberg. Doubts have been cast on the authorship of La Liga, as noted by Benedict Anderson. It is not easy to believe that this authoritarian structure, evidently adapted from Masonry’s ancestral lore, was Rizal’s brainchild… It is much more likely that structure was the brainchild of Andres Bonifacio, who formed the underground revolutionary Katipunan not long after Rizal’s deportation to Mindanao and the Liga’s abrupt disintegration (2005, 130). While it is true that no existing manuscript can be traced to Rizal, the Statutes was published in Hong Kong while he was living there and was disseminated to political activists in Manila whom he addressed in organized gatherings. Most significantly, he never denied authorship of it even though, as he averred truthfully at his trial, he had no knowledge of Volume 13949:1 (2013) 150140 G.