Martin Valerie I 201809 Phd.Pdf (2.587Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Needs You Volume One

Canada Needs You Volume One A Study Guide Based on the Works of Mike Ford Written By Oise/Ut Intern Mandy Lau Content Canada Needs You The CD and the Guide …2 Mike Ford: A Biography…2 Connections to the Ontario Ministry of Education Curriculum…3 Related Works…4 General Lesson Ideas and Resources…5 Theme One: Canada’s Fur Trade Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 2: Thanadelthur…6 Track 3: Les Voyageurs…7 Key Terms, People and Places…10 Specific Ministry Expectations…12 Activities…12 Resources…13 Theme Two: The 1837 Rebellion Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 5: La Patriote…14 Track 6: Turn Them Ooot…15 Key Terms, People and Places…18 Specific Ministry Expectations…21 Activities…21 Resources…22 Theme Three: Canadian Confederation Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 7: Sir John A (You’re OK)…23 Track 8: D’Arcy McGee…25 Key Terms, People and Places…28 Specific Ministry Expectations…30 Activities…30 Resources…31 Theme Four: Building the Wild, Wild West Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 9: Louis & Gabriel…32 Track 10: Canada Needs You…35 Track 11: Woman Works Twice As Hard…36 Key Terms, People and Places…39 Specific Ministry Expectations…42 Activities…42 Resources…43 1 Canada Needs You The CD and The Guide This study guide was written to accompany the CD “Canada Needs You – Volume 1” by Mike Ford. The guide is written for both teachers and students alike, containing excerpts of information and activity ideas aimed at the grade 7 and 8 level of Canadian history. The CD is divided into four themes, and within each, lyrics and information pertaining to the topic are included. -

Mesplet to Metadata: Canadian Newspaper Preservation and Access. PUB DATE 2001-08-00 NOTE 12P.; In: Libraries and Librarians: Making a Difference in the Knowledge Age

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 459 731 IR 058 225 AUTHOR Burrows, Sandra TITLE Mesplet to Metadata: Canadian Newspaper Preservation and Access. PUB DATE 2001-08-00 NOTE 12p.; In: Libraries and Librarians: Making a Difference in the Knowledge Age. Council and General Conference: Conference Programme and Proceedings (67th, Boston, MA, August 16-25, 2001); see IR 058 199. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.ifla.org. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141)-- Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Foreign Countries; *Library Collection Development; *Library Collections; *National Libraries; *Newspapers; Preservation IDENTIFIERS Historical Background; *National Library of Canada ABSTRACT This paper traces the development of the National Library of Canada's newspaper collection in conjunction with the Decentralized Program for Canadian Newspapers. The paper also presents a sampling from the collection in order to illustrate the rich variety of the press that has followed in the footsteps of Fleury Mesplet, one of the first printers of newspapers in North America. Highlights include: the history of newspaper publishing in Canada from 1752 to 1858; responsibilities of the National Library of Canada newspaper collection and preservation program; and achievements at the national and regional levels, including creation online of "The Union List of Canadian Newspapers." Special types of newspapers collected are described, including: special issues of Canadian newspapers such as Christmas/holiday issues, carnival issues, and souvenir issues; labor and alternative press newspapers; ethnic press newspapers; student press newspapers; and community press newspapers; and aboriginal newspapers. (Contains 18 references.)(Author/MES) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Living and Learning in New France, 1608-1760

CJSAEIRCEEA 23) Novemberlnovembre 2010 55 Perspectives "A COUNTRY AT THE END OF THE WORLD": LIVING AND LEARNING IN NEW FRANCE, 1608-1760 Michael R. Welton Abstract This perspectives essay sketches how men and women of New France in the 17th and 18th centuries learned to make a living , live their lives, and express themselves under exceptionally difficult circumstances. This paper works with secondary sources, but brings new questions to old data. Among other things, the author explores how citizen learning was forbidden in 17th- and 18th-century New France, and at what historical point a critical adult education emerged. The author's narrative frame and interpretation of the sources constitute one of many legitimate forms of historical inquiry. Resume Ce croquis d'essai perspective comment les hommes et les femmes de la Nouvelle-France au XVlIe et XV1I1e siecles ont appris a gagner leur vie, leur vie et s'exprimer dans des circonstances difficiles exceptionnellement. Cette usine papier avec secondaire sources, mais apporte de nouvelles questions d'anciennes donnees. Entre autres choses, I' auteur explore comment citoyen d' apprentissage a ete interdite en Nouvelle-France XVlIe-XV1I1e siecle et a quel moment historique une critique de ['education des adultes est apparu. Trame narrative de ['auteur et ['interpretation des sources constituent une des nombreuses formes legitimes d'enquete historique. The Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education/ La Revue canadienne pour i'ill/de de i'iducation des adultes 23,1 Novemberlnovembre 2010 55-71 ISSN 0835-4944 © Canadian Association for the Study of Adult Education! L' Association canadienne pour l' etude de I' education des adultes 56 Welton, ({Living and Learning in New France, 1608-1760" Introduction In the 1680s one intendant wrote that Canada has always been regarded as a country at the end of the world, and as a [place of] exile that might almost pass for a sentence of civil death, and also as a refuge sought only by numerous wretches until now to escape from [the consequences of] their crimes. -

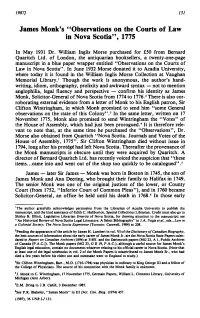

James Monk's “Observations on the Courts of Law in Nova Scotia”, 1775

James Monk’s “Observations on the Courts of Law in Nova Scotia” , 1775 In May 1931 Dr. William Inglis Morse purchased for £50 from Bernard Quaritch Ltd. of London, the antiquarian booksellers, a twenty-one-page manuscript in a blue paper wrapper entitled “Observations on the Courts of Law in Nova Scotia” . In June 1932 Morse donated it to Acadia University, where today it is found in the William Inglis Morse Collection at Vaughan Memorial Library.1 Though the work is anonymous, the author’s hand writing, idiom, orthography, prolixity and awkward syntax — not to mention anglophilia, legal fluency and perspective — confirm his identity as James Monk, Solicitor-General of Nova Scotia from 1774 to 1776.2 There is also cor roborating external evidence from a letter of Monk to his English patron, Sir Clifton Wintringham, in which Monk promised to send him “some General observations on the state of this Colony” .3 In the same letter, written on 17 November 1775, Monk also promised to send Wintringham the “Votes” of the House of Assembly, which had just been prorogued.4 It is therefore rele vant to note that, at the same time he purchased the “Observations” , Dr. Morse also obtained from Quaritch “Nova Scotia. Journals and Votes of the House of Assembly, 1775” . Sir Clifton Wintringham died without issue in 1794, long after his protégé had left Nova Scotia. Thereafter the provenance of the Monk manuscripts is obscure until they were acquired by Quaritch. A director of Bernard Quaritch Ltd. has recently voiced the suspicion that “ these items...came into and went out of the shop too quickly to be catalogued” .5 James — later Sir James — Monk was born in Boston in 1745, the son of James Monk and Ann Deering, who brought their family to Halifax in 1749. -

Bishop's Gambit: the Transatlantic Brokering of Father Alexander

Bishop’s Gambit: The Transatlantic Brokering of Father Alexander Macdonell by Eben Prevec B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2018 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July 2020 © Eben Prevec, 2020 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the thesis entitled: Bishop’s Gambit: The Transatlantic Brokering of Father Alexander Macdonell submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements by Eben Prevec for the degree of Master of Arts in History Examining Committee: Dr. Michel Ducharme, Associate Professor, Department of History, UBC Supervisor Dr. Bradley Miller, Associate Professor, Department of History, UBC Supervisory Committee Member Dr. Tina Loo, Professor, Department of History, UBC Additional Examiner i Abstract This thesis examines the transatlantic life and journey of Father Alexander Macdonell within the context of his role as a broker in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While serving as a leader for the Glengarry Highlanders throughout the British Isles and Upper Canada, Macdonell acted as a middleman, often brokering negotiations between his fellow Highlanders and the British and Upper Canadian governments. This relationship saw Macdonell and the Glengarry Highlanders travel to Glasgow, Guernsey, and Ireland, working as both manufacturers and soldiers before they eventually settled in Glengarry County, Upper Canada. Once established in Upper Canada, Macdonell continued to act as a broker, which notably led to the participation of the Glengarry Highlanders in the colony’s defence during the War of 1812. -

Slave Ads of the Montreal Gazette 1785 -1805

"To Be Sold: A Negro Wench" Slave Ads of the Montreal Gazette 1785 -1805 Tamara Extian-Babiuk Department of Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal February 2006 A thesis submitted to Mc Gill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master's ofArts © Tamara Extian-Babiuk 2006 Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-24859-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-24859-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell th es es le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Quebec During the American Invasion, 1775-1776

Quebec During the American Invasion, 1775-1776: The Journal of François Baby, Gabriel Taschereau, and Jenkin Williams Available for the first time in English, the 1776 journal of François Baby, Gabriel Taschereau, and Jenkin Williams provides an insight into the failure to incite rebellion in Québec by American revolutionaries. While other sources have shown how British soldiers and civilians and the French-Canadian gentry (the seigneurs) responded to the American invasion of 1775–1776, this journal focuses on French-Canadian peasants (les habitants) who made up the vast majority of the population; in other words, the journal helps explain why Québec did not become the "fourteenth colony." 1 After American forces were expelled from Québec in early 1776, the British governor, Sir Guy Carleton, sent three trusted envoys to discover who had collaborated with the rebels from the south. They traveled to fifty-six parishes and missions in the Québec and Trois Rivières district, discharging disloyal militia officers and replacing them with faithful subjects. They prepared a report on each parish, revealing actions taken to support the Americans or the king. Baby and his colleagues documented a wide range of responses. Some habitants enlisted with the Americans; others supplied them with food, firewood, and transportation. Some habitants refused to cooperate with the king’s soldiers. In some parishes, women were the Americans’ most zealous supporters. Overall, the Baby Journal clearly reveals that the habitants played an important, but often overlooked, role in the American invasion. Testimony of James Thompson I, James Thompson of the city of Quebec, in the Province of Lower Canada, do testify and declare: That I served in the capacity of an Assistant Engineer during the siege of the city, invested during the years 1775 and 1776 by the American forces under the command of the late Major General Richard Montgomery. -

V*7 •Vxvca Ottawa, Canada, 1966 ^

001065 UNIVERSITY D OTTAWA ECOLE DES GRADUES THE ENGLISH V13.»POINT ON THE PROPOSED UNION OF 1822 TO UNITE THE PROVINCES ^F LOV.EK AND UPPErt CANADA by Robert P. Burns Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa as partial fulfilment of the reoauirements for the degree of Master of Arts 0£LA6/Si/0 -> % % \^1 •HI .v V*7 •vXVcA Ottawa, Canada, 1966 ^ UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UMI Number: EC55933 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC55933 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 UNIVERSITE D OTTAWA ECOLE DES GRADUES TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter page INTRODUCTION v I.-CONSIDERATIONS ON THE QUESTION OF UNION: 1788-1821 1 II.-PREPARATION OF THE UNION BILL AT THE COLONIAL OFFICE • . 59 III.-THE CANADA BILL OF 1822 IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS 132 IV.-REACTIONS TO THE UNION BILL OF 1822 IN THE CANADAS 182 CONCLUSION 280 Appendix 1. A BILL (AS AMENDED BY THE COMMITTEE) FOR UNITING THE LEGISLATURES OF LOwER AND UPPER CANADA 289 2. -

Formes Et Maîtres Étrangers De L'espace Public Canadien

Document generated on 09/30/2021 3:10 p.m. Voix et Images Formes et maîtres étrangers de l’espace public canadien Foreign Masters and Forms in Canadian Public Space Formas y maestros extranjeros del espacio público canadiense Denis Saint-Jacques Le dix-neuvième siècle québécois et ses modèles européens Article abstract Volume 32, Number 3 (96), printemps 2007 In this article, the author examines seminal works of prose essayists in French Canada in the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Texts by URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/016576ar Pierre du Calvet, Étienne Parent, François-Xavier Garneau, Edmond de Nevers DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/016576ar and the first social sciences essayists of the early twentieth century are studied to identify the foreign influences that affected the form of their discourse. See table of contents From political essays to journalism, lectures, history and social sciences essays, analysis reveals a diversity of sources—including classical Latin, British, American, Roman Catholic and European—which combine with a dominant French presence. Publisher(s) Université du Québec à Montréal ISSN 0318-9201 (print) 1705-933X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Saint-Jacques, D. (2007). Formes et maîtres étrangers de l’espace public canadien. Voix et Images, 32(3), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.7202/016576ar Tous droits réservés © Université du Québec à Montréal, 2007 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Analyzing the Parallelism Between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S. Greene Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Canadian History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Greene, Daniel S., "Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement" (2011). Honors Theses. 988. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/988 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement By Daniel Greene Senior Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Department of History Union College June, 2011 i Greene, Daniel Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement My Senior Project examines the parallelism between the movement to bring baseball to Quebec and the Quebec secession movement in Canada. Through my research I have found that both entities follow a very similar timeline with highs and lows coming around the same time in the same province; although, I have not found any direct linkage between the two. My analysis begins around 1837 and continues through present day, and by analyzing the histories of each movement demonstrates clearly that both movements followed a unique and similar timeline. -

1 the Most Honourable Order of the Bath Gcb / Kcb / Cb X

THE MOST HONOURABLE ORDER OF THE BATH GCB / KCB / CB X - CB - 2020 PAGES: 59 UPDATED: 01 September 2020 Prepared by: Surgeon Captain John Blatherwick, CM, CStJ, OBC, CD, BSc, MD, FRCP(C), LLD (Hon) ===================================================================================================================== ===================================================================================================================== 1 THE MOST HONOURABLE ORDER OF THE BATH (GCB / KCB / CB) When the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick, National Order for Ireland was phased out with the death of the Duke of Gloucester in 1974, the Order of the Bath became the third highest Order of Chivalry. Merit and Service were to be the conditions for admission to this Order as opposed to most admissions to the Garter and Thistle being because of birth and nobility. The Order was founded in 1399 and probably took its name from the preparations for the knighthood ceremony where new knights would purify their inner souls by fasting, vigils and prayer, and then cleansing their body by immersing themselves in a bath. The Order was revived in 1725 as a military order with one class of Knights (K.B.). In 1815, the Order was enlarged to three classes: Knights Grand Cross (GCB) Knights Commander (KCB) Companions (CB) There was a civil division of the Knights Grand Cross while all others were to be military officers. In 1847, a civil division for all three classes was established with numbers set as follows: GCB 95 total 68 military 27 civil KCB 285 total 173 military 112 civil CB 1,498 total 943 military 555 civil The motto of the order is " Tria Juncta in Uno " (Three joined in one) which either refers to the three golden crowns within a golden circle worn on the badge, or the three crowns as symbolic of the Union of England, France and Scotland, or the Union of England, Scotland and Ireland or the Holy Trinity. -

Pierre De Sales Laterrière, Aventurier-Mémorialiste (1743-1815)

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL L'INVENTION D'UNE VIE : PIERRE DE SALES LATERRIÈRE, AVENTURIER-MÉMORIALISTE (1743-1815) MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN ÉTUDES LITTÉRAIRES PAR LISANDRE BOULANGER JUIN 2010 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 - Rév.01-2006). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de publication oe la totalité ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l'auteur] autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf ententè contraire, [l'auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» REMERCIEMENTS Je remercie mes codirecteurs, Madame Lucie Desjardins et Monsieur Bernard Andrès. Je suis particulièrement reconnaissante à ce dernier pour sa patience, ses encouragements et son enthousiasme inépuisable. Je n'oublie pas ses nombreux conseils éclairés qui ont su me guider tout au long de la rédaction.