V*7 •Vxvca Ottawa, Canada, 1966 ^

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Monk's “Observations on the Courts of Law in Nova Scotia”, 1775

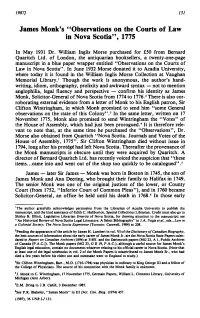

James Monk’s “Observations on the Courts of Law in Nova Scotia” , 1775 In May 1931 Dr. William Inglis Morse purchased for £50 from Bernard Quaritch Ltd. of London, the antiquarian booksellers, a twenty-one-page manuscript in a blue paper wrapper entitled “Observations on the Courts of Law in Nova Scotia” . In June 1932 Morse donated it to Acadia University, where today it is found in the William Inglis Morse Collection at Vaughan Memorial Library.1 Though the work is anonymous, the author’s hand writing, idiom, orthography, prolixity and awkward syntax — not to mention anglophilia, legal fluency and perspective — confirm his identity as James Monk, Solicitor-General of Nova Scotia from 1774 to 1776.2 There is also cor roborating external evidence from a letter of Monk to his English patron, Sir Clifton Wintringham, in which Monk promised to send him “some General observations on the state of this Colony” .3 In the same letter, written on 17 November 1775, Monk also promised to send Wintringham the “Votes” of the House of Assembly, which had just been prorogued.4 It is therefore rele vant to note that, at the same time he purchased the “Observations” , Dr. Morse also obtained from Quaritch “Nova Scotia. Journals and Votes of the House of Assembly, 1775” . Sir Clifton Wintringham died without issue in 1794, long after his protégé had left Nova Scotia. Thereafter the provenance of the Monk manuscripts is obscure until they were acquired by Quaritch. A director of Bernard Quaritch Ltd. has recently voiced the suspicion that “ these items...came into and went out of the shop too quickly to be catalogued” .5 James — later Sir James — Monk was born in Boston in 1745, the son of James Monk and Ann Deering, who brought their family to Halifax in 1749. -

Martin Valerie I 201809 Phd.Pdf (2.587Mb)

The Honest Man/L’Homme Honnête: The Colonial Gentleman, the Development of the Press, and the Race and Gender Discourses of the Newspapers in the British “Province of Quebec,” 1764-1791 By Valérie Isabelle Martin A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in History in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2018 Copyright © Valérie Isabelle Martin, 2018 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the new public world of print that emerged and developed in the “Province of Quebec” from 1764 to 1791. Using discourse analysis, it argues that the press reflected, and contributed to producing the race and gender privileges of the White, respectable gentleman, also called the “honest man,” regardless of whether he was Canadien or of Anglo-descent. A British colony created by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the Province of Quebec existed until 1791 when it was divided into the separate colonies of Upper and Lower Canada by the Constitutional Act. The colony’s development and dissolution corresponded with a growing population and changing demographics in the Saint Lawrence Valley, a brief increase in racial slavery in Montreal and Quebec City, and altered political and economic alliances between the White settler population and Native peoples of the North American interior after the defeat of the French in 1763 and following the emergence of the American Republic in 1783. Internally, changes brought about by the conclusion of the British Conquest in 1760, such as the introduction of British rule and English law in Quebec, were implemented alongside French ancien régime structures of legal and political governance that persisted mostly unhampered and fostered the preservation of an authoritarian-style government in the new “old” colony. -

John Wollaston, Port

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy o f the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of die original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.Tha sign or "?c.,§€t" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Mining Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. Youa will find good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. I t is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Slave in Canada

THE SLAVE IN CANADA BY The Honorable WILLIAM RENWICK RIDDELL LL.D,; F. R. Hist. Soc; F. R. Soc. Can.; &c, &c. JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF ONTARIO JJ-; Reprinted from The Journal of Negro History, Vol. V, No. 3, July, 1920 THE ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF NEGRO LIFE AND HISTORY WASHINGTON, D. C. 1920 THE SLAVE IN CANADA BY The Honorable WILLIAM RENWICK RIDDELL LL.D.; F. R. Hist. Soc; F. R. Soc. Can.; &c, &c. JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF ONTARIO s;kif£ Reprinted from The Journal of Negro History, Vol. V, No. 3, Juiy, 1920 • •> •» ) -I 1 ) ) • 1 J ) THE ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF NEGRO LIFE AND HISTORY WASHINGTON, D. C. 1920 / / *7 / ft> i PRESS OF THE NEW ERA PRINTING COMPANY LANCASTER, PA. it. ifxi, 6 I • • • a • • •• « • • * • • » PREFACE When engaged in a certain historical inquiry, I found occasion to examine the magnificent collection of the Cana- dian Archives at Ottawa, a collection which ought not to be left unexamined by anyone writing on Canada. In that inquiry I discovered the proceedings in the case of Chloe Cooley set out in Chapter V of the text. This induced me to make further researches on the subject of slavery in Upper Canada. The result was incorporated in a paper, The Slave in Upper Canada, read before the Eoyal Society of Canada in May 1919, and subsequently published in the Journal of Negro History for October, 1919. Some of the Fellows of the Royal Society of Canada and the editor of the Journal of Negro History have asked me to ex- pand the paper. -

Reference Department

TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY. Reference Department THIS BOOK MUST iIIOT BE TAKEN OUT Of THE ROOM . • ~. /' Eu_gY;I: 't'cL ".y E. Ht·,u."t.-../ --v / ../ \ \ / \ \ < / // \ / \ 100 0 <: "at~ o:f Ee En_gl-;l r (l tJ)' b. B I'"" C't . -../ \ ../ \ \ \ \ i \ \ / • F ,. In.: (L J' () \ \ \ / / \ / '\1'" t / \ • / • !rUE QUEBEC DIRECTORY, ~c. THE ~ utbtt IJfrttforYt, FOR 1'8Q~; COrNTAlNING AN A-LPHABETICAL LIST OF TIrE MERCHAN'.l'S, TRADERS,- AND· HOUSE KEEPERS, &c. WITHIN THE CITY, TO WHICH' IS PREFIXi:D A DESCRIf'TIVE SKETCH OF THZ TOWN 'JlOCETI'lER WITH ·AN APPENDIX CONTAINING AN ABSTRAC'£ OF THE llEG rlLATIOSS OF POLICE" <-Ye. "'c~ BY THOMAS HENRI GLEASON~ PRICE, SIX AND 'DHREr PENCE.; QUEBEC: J'RINTED BY. NEILSON AND COWAN, PRINTl!;RS AND EOOICSIl:LIRs', NQ. 15, MOUN·TJ\IN STREET. 18~2. ~ablt of Utfttttttt. --»fgj'.€-c€!-="'- 1. Gun Boat Wharf. A. Castle of St. LOllis. ~. Symes' Wharf. B. Bishops' Palace &c. 3. Heath & Moir. C. Court House, 4. Cape Diamond Brewery. D. English Cathedral. 5. Joncs' Wharf. E. French Cathedral. fi. Andersons' do. F. Seminary:. 7. Irvines' do. G Hotel Dieu Nunn~rY, 8. Finlays' do. Church and Gardens. - 9. King's Wharf and Stores. H. U"sulines do. do. do. 10. Brunettes' Wharf. I. Jesuit's Barrack, and Dl"ill 11. Queens' do. Ground. 12. IVI'Callums'do. K. Presbyterian Church. 1:;. Pattersons' do. L. Gaol. 14. Goudies' do. M. Commissariat Office. 15. Bells" do. N. Con:rreganiste Church. 16. Quirouet,' Brewery. O. King's Works Office. 17. Dumas Wharf. P. St. Louis St. Barrack &c. 1 R. -

The Quebec Library and the Transatlantic Enlightenment in Canada Michael Eamon

Document generated on 10/01/2021 2:20 p.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada “An Extensive Collection of Useful and Entertaining Books”: The Quebec Library and the Transatlantic Enlightenment in Canada Michael Eamon Volume 23, Number 1, 2012 Article abstract At the height of the American Revolution in 1779, the Quebec Library was URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1015726ar created by Governor Sir Frederick Haldimand. For Haldimand, the library had DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1015726ar a well-defined purpose: to educate the public, diffuse useful knowledge, and bring together the French and English peoples of the colony. Over the years, See table of contents the memory of this institution has faded and the library has tended to be framed as an historical curiosity, seemingly divorced from the era in which it was created. This paper revisits the founding and first decades of this Publisher(s) overlooked institution. It argues that its founder, trustees, and supporters were not immune to the spirit of Enlightenment that was exhibited elsewhere in the The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada British Atlantic World. When seen as part of the larger social and intellectual currents of the eighteenth century, the institution becomes less of an historical ISSN enigma and new light is shed on the intellectual culture of eighteenth-century Canada. 0847-4478 (print) 1712-6274 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Eamon, M. (2012). “An Extensive Collection of Useful and Entertaining Books”: The Quebec Library and the Transatlantic Enlightenment in Canada. -

Report on Lord Dalhousie's History on Slavery and Race

Report on Lord Dalhousie’s History on Slavery and Race AUGUST, 2019 Scholarly panel Dr. Afua Cooper: Chair Professor Françoise Baylis Dean Camille Cameron Mr. Ainsley Francis Dr. Paul Lovejoy Mr. David States Dr. Shirley Tillotson Dr. H.A. Whitfield Ms. Norma Williams Research Support Ms. Jalana Lewis, Lead Researcher Ms. Kylie Peacock Mr. Wade Pfaff With contributions from Dr. Karly Kehoe and Dr. Isaac Saney 3 REPORT ON LORD DALHOUSIE’S HISTORY ON SLAVERY AND RACE COVER: MEMORIAL OF GABRIEL HALL OF PRESTON, A BLACK REFUGEE WHO EMIGRATED TO THE COLONY OF NOVA SCOTIA DURING THE WAR OF 1812 PHOTOGRAPHER GEORGE H. CRAIG, MARCH 1892 COURTESY: NOVA SCOTIA ARCHIVES Table of Contents Note from Dr. Teri Balser, Interim President and Vice-Chancellor.....................................................................................6 Note from Dr. Afua Cooper, Chair of the Panel and Lead Author of the Report ...............................................................7 Foreward to the Lord Dalhousie Report by Dr. Kevin Hewitt, Chair of the Senate ...........................................................9 Executive Summary for the Lord Dalhousie Report .........................................................................................................11 1.0 Dalhousie University’s Historic Links to Slavery and its Impact on the Black Community: Rationale for the Report ............................................................................................................................................17 1.1 Dalhousie College: A legacy -

A Bibliography of Loyalist Source Material in Canada

A Bibliography of Loyalist Source Material in Canada JO-ANN FELLOWS, Editor KATHRYN CALDER, Researcher PROGRAM FOR LOYALIST STUDIES AND PUBLICATIONS Sponsored by the American Antiquarian Society City University of New Tork University of London and University of New Brunswick by ROBERT A. EAST, Executive Director The origins of this Program are to be found in the pros- pectus issued in April 1968 by Professor East of the History faculty of the City University of New York and James E. Mooney, Editor of Publications of the American Antiquarian Society. It was the feeling of both that the imminent anniversary of the Revolution would make such an undertaking an impera- tive of historical scholarship, for an understanding of the Rev- olution would be necessarily incomplete and inevitably dis- torted without the full story of the American Loyalists. It was the hope of both that the work could go forward under the joint sponsorship of both institutions, and this was quickly gained. The next step was to canvass the scholarly community in England, Canada, and the United States to learn of its reac- 67 68 American Antiquarian Society tions. The prospectus was written, handsomely printed by Alden Johnson of the Barre Publishers, and sent out to a number of scholars, archivists, and others. The response to this mailing was even more enthusiastic than Professor East or Mr. Mooney had hoped for and led to discussions concerning even broader sponsorship of an inter- national character. Thomas J. Condon ofthe American Council of Learned Societies early took a cheering interest in the proj- ect and pledged the cooperation of his august organization to advance the work. -

Lande Collection / Collection Lande

Canadian Archives Direction des archives Branch canadiennes LANDE COLLECTION / COLLECTION LANDE MG 53 Finding Aid No. 1483 / Instrument de recherche no 1483 Prepared in 1979 par Michelle Corbett and Préparé en 1979 par Michelle Corbett et completed between 1987 and 1996 by Andrée complété entre 1987 et 1996 par Andrée Lavoie for the Social and Cultural Archives Lavoie pour les Archives sociales et culturelles Lawrence Lande Collection/Collection Lawrence Lande MG 53 Finding Aid No./Instrument de recherche no 1483 TABLE OF CONTENTS / TABLE DES MATIÈRES Page List of unacquired collections / Liste des collections non acquises .................... 1 Microfilm ............................................................... 2 List of microfilm reels / Liste des bobines de microfilm ............................ 4 Volumes numbers of original documents / Numéros de volumes des documents originaux.................................................... 9 Alphabetical List of collections / Liste alphabétique des collections .............. 20-38 Ordre numérique ..........................................................39 LIST OF UNACQUIRED NUMBERS / LISTE DES NUMÉROS NON ACQUIS These numbers corresponding with collections described in the Canadian Historical Documents & Manuscripts from the Private Collection of Lawrence M. Lande with his notes and observations have not been acquired by the National Archives of Canada. Some of them are at the National Library of Canada and at McGill University in Montreal. Ces numéros correspondant à des collections -

King's College, Nova Scotia: Direct Connections with Slavery

King’s College, Nova Scotia: Direct Connections with Slavery by Karolyn Smardz Frost, PhD David W. States, MA Presented to William Lahey, President, University of King’s College and Dorota Dr. Glowacka, Chair, "King's and Slavery: A Scholarly Inquiry" September 2019 King’s College, Windsor, Nova Scotia, ca. 1850 Owen Staples, after Susannah Lucy Anne (Haliburton) Weldon Cover image King's College, Windsor, Nova Scotia, ca 1850 by Owen Staples (1910), after Susannah Lucy Anne (Haliburton) Weldon’s original This painting depicts the main building constructed in 1791, prior to the 1854 addition of a portico and the gable roof. Brown wash over pencil, with water colour & gouache by Owen Staples? ca 1915. Laid down on cardboard. JRR 2213 Cab II, John Ross Robertson Collection, Baldwin Room, Toronto Reference Library Public domain 1 Preface Over the past few years, universities in Canada, the United States, Great Britain, and beyond have undertaken studies exploring the connections between slavery and the history of their institutions. In February 2018, the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia, initiated its own investigations to bring to light ways in which slavery and the profits derived from trade in the products of enslaved labour contributed to the creation and early operation of King’s, Canada’s oldest chartered university. David W. States, a historian of African Nova Scotia with a multi-generational personal heritage in this province, and Karolyn Smardz Frost, an archaeologist, historian and author whose studies focus on African Canadian and African American transnationalism, were chosen to become part of a small cadre of scholars charged with the task of bringing different aspects of this long-hidden history to light. -

The Fight for Bourgeois Law in Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1749-1753

The Fight for Bourgeois Law in Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1749-1753 JAMES MUIR* In the new colony of Halifax, merchants and other members of the colonial bourgeois desired a legal order that would support their commercial needs, not impede their activities, and that included members of their class. In a series of legal disputes between 1749 and 1753 the bourgeois fought for their interests in front of and against the colony’s government. In each case, the merchants and their allies lost the specific legal dispute but secured changes in the legal regime that better met their expectations. Dans la nouvelle colonie de Halifax, les marchands et d’autres membres de la bourgeoisie coloniale ont voulu avoir un ordre juridique qui irait dans le sens de leurs besoins commerciaux, sans entraver leurs activités, et qui inclurait des membres de leur classe. Dans une série de litiges survenus entre 1749 et 1753, les bourgeois ont lutté pour leurs intérêts devant le gouvernement de la colonie et contre celui-ci. Dans chaque cas, les marchands et leurs alliés ont perdu leur cause en justice, mais ils ont obtenu des changements dans le régime juridique qui répondaient mieux à leurs attentes. IN EARLY SUMMER 1749, Colonel Edward Cornwallis led a convoy of 14 ships and 2,576 people to Chebucto Harbor, the site of Nova Scotia’s new capital, Halifax. Although many in the original convoy left, those who stayed were joined by others from the American colonies as well as England and Europe. The 1752 census found 4,248 people in the town and its suburbs.1 Halifax would not be just a military outpost against the French, but a fully functioning town and suburb, with farms nearby, a large number of artisans, and seafarers to take up fishing. -

Historical Collections. Collections and Researches Made by the Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society

Library of Congress Historical collections. Collections and researches made by the Michigan pioneer and historical society ... Reprinted by authority of the Board of state auditors. Volume 20 HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS COLLECTIONS AND RESEARCHES MADE BY THE Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society REPRINT 1912 Vol. XX M. AGNES BURTON DETROIT, MICH. LC LANSING, MICHIGAN WYNKOOP HALLENBECK CRAWFORD CO., STATE PRINTERS 1912 2d set F561 .M775 2d set Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1892, by the MICHIGAN PIONEER AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. In exchange 34 Louis Publishing Feb. 28, 1927 LC Historical collections. Collections and researches made by the Michigan pioneer and historical society ... Reprinted by authority of the Board of state auditors. Volume 20 http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.5298i Library of Congress PREFACE F. B. M. 1927-3-4 This, the twentieth volume of Pioneer and Historical Collections, as well as volume 19, is entirely devoted to copies of original documents from the Canadian Archives at Ottawa, relating to Michigan and its environs. The “Haldimand Papers” are a continuation of the same from volume 19, beginning with the year 1782, and carries them to a finish in 1789, covering the period of the closing of the Revolutionary war, and the establishing of peace between Great Britain and the United States, and the evacuation of some of the Upper Military Posts, and comprises nearly half of the volume. The papers devoted to “Indian Affairs” cover a period from 1761 to 1800, and contain a mass of correspondence relative to the Indian Department and the Indian war with the United States.