Exploring the Architecture of Bali Post Hasta Kosala Kosali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

KAJIAN PENDAHULUAN TEMUAN STRUKTUR BATA DI SAMBIMAYA, INDRAMAYU The Introduction Study of Brick Structural Found in Sambimaya, Indramayu Nanang Saptono,1 Endang Widyastuti,1 dan Pandu Radea2 1 Balai Arkeologi Jawa Barat, 2 Yayasan Tapak Karuhun Nusantara 1Jalan Raya Cinunuk Km. 17, Cileunyi, Bandung 40623 1Surel: [email protected] Naskah diterima: 24/08/2020; direvisi: 28/11/2020; disetujui: 28/11/2020 publikasi ejurnal: 18/12/2020 Abstract Brick has been used for buildings for a long time. In the area of Sambimaya Village, Juntinyuat District, Indramayu, a brick structure has been found. Based on these findings, a preliminary study is needed for identification. The problem discussed is regarding the type of building, function, and timeframe. The brick structure in Sambimaya is located in several dunes which are located in a southwest-northeastern line. The technique of laying bricks in a stack without using an adhesive layer. Through the method of comparison with other objects that have been found, it was concluded that the brick structure in Sambimaya was a former profane building dating from the early days of the spread of Islam in Indramayu around the 13th - 14th century AD. Keywords: Brick, structure, orientation, profane Abstrak Bata sudah digunakan untuk bangunan sejak lama. Sebaran struktur bata telah ditemukan di kawasan Desa Sambimaya, Kecamatan Juntinyuat, Indramayu. Berdasarkan temuan itu perlu kajian pendahuluan untuk identifikasi. Permasalahan yang dibahas adalah mengenai jenis bangunan, fungsi, dan kurun waktu. Struktur bata di Sambimaya berada pada beberapa gumuk yang keletakannya berada pada satu garis berorientasi barat daya – timur laut. Teknik pemasangan bata secara ditumpuk tanpa menggunakan lapisan perekat. -

Marginalization of Bali Traditional Architecture Principles

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture Available online at https://sloap.org/journals/index.php/ijllc/ Vol. 6, No. 5, September 2020, pages: 10-19 ISSN: 2455-8028 https://doi.org/10.21744/ijllc.v6n5.975 Marginalization of Bali Traditional Architecture Principles a I Kadek Pranajaya b I Ketut Suda c I Wayan Subrata Article history: Abstract The traditional Balinese architecture principles have been marginalized and Submitted: 09 June 2020 are not following Bali Province Regulation No. 5 of 2005 concerning Revised: 18 July 2020 Building Architecture Requirements. In this study using qualitative analysis Accepted: 27 August 2020 with a critical approach or critical/emancipatory knowledge with critical discourse analysis. By using the theory of structure, the theory of power relations of knowledge and the theory of deconstruction, the marginalization of traditional Balinese architecture principles in hotel buildings in Kuta Keywords: Badung Regency is caused by factors of modernization, rational choice, Balinese architecture; technology, actor morality, identity, and weak enforcement of the rule of law. hotel building; The process of marginalization of traditional Balinese architecture principles marginalization; in hotel buildings in Kuta Badung regency through capital, knowledge-power principles; relations, agency structural action, and political power. The implications of traditional; the marginalization of traditional Balinese architecture principles in hotel buildings in Kuta Badung Regency have implications for the development of tourism, professional ethics, city image, economy, and culture of the community as well as for the preservation of traditional Balinese architecture. International journal of linguistics, literature and culture © 2020. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). -

Akulturasi Di Kraton Kasepuhan Dan Mesjid Panjunan, Cirebon

A ULTURASI DI KRATON KA URAN DAN MESJID PANJUNAN, CIREBON . Oleh: (.ucas Partanda Koestoro . I' ... ,.. ': \.. "\.,, ' ) ' • j I I. ' I Pendukung kebiidayaan adalati manusia. Sejak kelahirannya dan dalam proses scis.ialisasi, manusia mendapatkan berbagai pengetahu an. Pengetahuan yang didapat dart dipelajari dari lingkungan keluarga pada lingkup. kecil dan m~syarakat pa.da. lingkup besar, mendasari da:µ mendorong tingkah lakunya. .dalam mempertahankan hidup. Sebab m~ri{isjq ti.da.k , bertin~a~ hanya k.a.rena adanya dorongan untuk hid up s~ja, tet~pi i1:1g~ kp.rena ~ua~u desakan baru yang berasal dari ·budi ma.nusia dan menjadi dasar keseluruhan hidupnya, yang din<lmakan - · ~ \. ' . kebudayaan. Sehingga s~atu . masyarakat ketik? berhadapan dan ber- i:riteraksi dengan masyarakat lain dengan kebudayaan yang berlainan, kebudayaan baru tadi tidak langsung diterima apa adanya. Tetapi dinilai dan diseleksi mana yang sesuai dengan kebudayaannya sendiri. Budi manusia yang menilai ben.da dan kejp.dian yang beranek~ ragam di sekitarhya kemudian memllihnya untuk dijadikan tujuan maupun isi kelakuan ·buda\ranva (Su tan Takdir Alisyahbana, tanpa angka tahun: 4 dan 7). · · II. Data sejarah yang sampai pada kita dapat memberikan petunjuk bahwa masa Indonesia-Hindu selanjutnya digantikan oleti masa Islam di Indonesia. Kalau pada masa Indonesia-Hindu pengaruh India men~ jadi faktor yang utama dalam perkembangari budaya masyarakat Iri donesia, maka dalam masa Islam di Indonesia, Islam pun inenjadi fak tor yang berpengaruh pula. Adapun pola perkembangan kebudayaan Indonesia pada masa masuknya pengaruh Islam~ pada dasarnya 'tidak banyak berbeda dengan apa yang terjadi dalam proses masuknya pe ngaruh Hindu. Kita jumpai perubahan-perubahan dalam berbagai bi dang . -

R. Tan the Domestic Architecture of South Bali In: Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 123 (1967), No: 4, Leiden, 442-4

R. Tan The domestic architecture of South Bali In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 123 (1967), no: 4, Leiden, 442-475 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 05:53:05PM via free access THE DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE OF SOUTH BALI* outh Bali is the traditional term indicating the region south of of the mountain range which extends East-West across the Sisland. In Balinese this area is called "Bali-tengah", maning centra1 Bali. In a cultural sense, therefore, this area could almost be considered Bali proper. West Lombok, as part of Karangasem, see.ms nearer to this central area than the Eastern section of Jembrana. The narrow strip along the Northern shoreline is called "Den-bukit", over the mountains, similar to what "transmontane" mant tol the Romans. In iwlated pockets in the mwntainous districts dong the borders of North and South Bali live the Bali Aga, indigenous Balinese who are not "wong Majapahit", that is, descendants frcm the great East Javanece empire as a good Balinese claims to be.1 Together with the inhabitants of the island of Nusa Penida, the Bali Aga people constitute an older ethnic group. Aernoudt Lintgensz, rthe first Westemer to write on Bali, made some interesting observations on the dwellings which he visited in 1597. Yet in the abundance of publications that has since followed, domstic achitecture, i.e. the dwellings d Bali, is but slawly gaining the interest of scholars. Perhaps ,this is because domestic architecture is overshadowed by the exquisite ternples. -

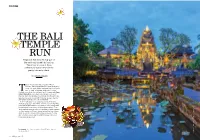

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

GROY Groenewegen, JM (Johannes Martinus / Han)

Nummer Toegang: GROY Groenewegen, J.M. (Johannes Martinus / Han) / Archief Het Nieuwe Instituut (c) 2000 This finding aid is written in Dutch. 2 Groenewegen, J.M. (Johannes Martinus / Han) / GROY Archief GROY Groenewegen, J.M. (Johannes Martinus / Han) / 3 Archief INHOUDSOPGAVE BESCHRIJVING VAN HET ARCHIEF......................................................................5 Aanwijzingen voor de gebruiker.......................................................................6 Citeerinstructie............................................................................................6 Openbaarheidsbeperkingen.........................................................................6 Archiefvorming.................................................................................................7 Geschiedenis van de archiefvormer.............................................................7 Groenewegen, Johannes Martinus............................................................7 BESCHRIJVING VAN DE SERIES EN ARCHIEFBESTANDDELEN........................................13 GROY.110659917 supplement........................................................................63 BIJLAGEN............................................................................................. 65 GROY Groenewegen, J.M. (Johannes Martinus / Han) / 5 Archief Beschrijving van het archief Beschrijving van het archief Naam archiefblok: Groenewegen, J.M. (Johannes Martinus / Han) / Archief Periode: 1948-1970, (1888-1980) Archiefbloknummer: GROY Omvang: 1,86 meter Archiefbewaarplaats: -

13543 Dwijendra 2020 E.Docx

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 13, Issue 5, 2020 Analysis of Symbolic Violence Practices in Balinese Vernacular Architecture: A case study in Bali, Indonesia Ngakan Ketut Acwin Dwijendraa, I Putu Gede Suyogab, aUdayana University, Bali, Indonesia, bSekolah Tinggi Desain Bali, Indonesia, Email: [email protected], [email protected] This study debates the vernacular architecture of Bali in the Middle Bali era, which was strongly influenced by social stratification discourse. The discourse of social stratification is a form of symbolic power in traditional societies. Through discourse, the power practices of the dominant group control the dominated, and such dominance is symbolic. Symbolic power will have an impact on symbolic violence in cultural practices, including the field of vernacular architecture. This study is a qualitative research with an interpretive descriptive method. The data collection is completed from literature, interviews, and field observations. The theory used is Pierre Bourdieu's Symbolic Violence Theory. The results of the study show that the practice of symbolic violence through discourse on social stratification has greatly influenced the formation or appearance of residential architecture during the last six centuries. This symbolic violence takes refuge behind tradition, the social, and politics. The forms of symbolic violence run through the mechanism of doxa, but also receive resistance symbolically through heterodoxa. Keywords: Balinese, Vernacular, Architecture, Symbolic, Violence. Introduction Symbolic violence is a term known in Pierre Bourdieu's thought, referring to the use of power over symbols for violence. Violence, in this context, is understood not in the sense of radical physical violence, for example being beaten, open war, or the like, but more persuasive. -

Magisterarbeit

MAGISTERARBEIT Titel der Magisterarbeit Synkretismen im Sakral- und Profanbau Javas Eine globalgeschichtliche Perspektive Verfasserin Desiree Weiler B.A. angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 805 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Magisterstudium der Globalgeschichte Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr.techn. Erich Lehner Ich erkläre ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende wissenschaftliche Arbeit selbstständig angefertigt und die mit ihr unmittelbar verbundenen Tätigkeiten selbst erbracht habe. Ich erkläre weiters, dass ich keine anderen als die angegebenen Hilfsmittel benutzt habe. Alle ausgedruckten, ungedruckten oder dem Internet im Wortlaut oder im wesentlichen Inhalt übernommenen Formulierungen und Konzepte sind gemäß den Regeln für wissenschaftliche Arbeiten zitiert. Die während des Arbeitsvorganges gewährte Unterstützung einschließlich signifikanter Betreuungshinweise ist vollständig angegeben. Die wissenschaftliche Arbeit ist noch keiner anderen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt worden. Diese Arbeit wurde in gedruckter und elektronischer Form abgegeben. Ich bestätige, dass der Inhalt der digitalen Version vollständig mit dem der gedruckten Version übereinstimmt. Ich bin mir bewusst, dass eine falsche Erklärung rechtliche Folgen haben wird. Wien, am Dank an: Familie Weiler Ana Purwa Laura Sprenger Helmut Rachl Lucia Denkmayr Katharina Höglinger Christian Tschugg Marc Carnal Prof. Dr. Erich Lehner Dr. Ir. Ikaputra Gadjah Mada Universität in Yogyakarta 4 Inhaltsverzeichnis -

Pakuwon Pada Masa Majapahit: Kearifan Bangunan Hunian Yang Beradaptasi Dengan Lingkungan

Pakuwon Pada Masa Majapahit: Kearifan Bangunan Hunian yang Beradaptasi dengan Lingkungan Agus Aris Munandar Departemen Arkeologi, Fakultas Ilmu Pengetahuan Budaya, Universitas Indonesia [email protected] Abstrak Berdasarkan data relief yang dipahatkan pada dinding candi-candi zaman Majapahit (Abad k-14—15 M), dapat diketahui adanya penggambaran gugusan perumahan yang ditata dengan aturan tertentu. Sumber tertulis antara lain Kitab Nagarakrtagama menyatakan bahwa gugusan perumahan dengan komposisi demikian lazim dinamakan dengan Pakuwon (pa+kuwu+an). Kajian yang diungkap adalah perihal bentuk-bentuk bangunan dalam gugusan Pakuwon, keletakannya pada natar (halaman) sesuai arah mata angin, dan juga fungsi serta maknanya dalam kebudayaan masa itu. Bentuk bangunan hunian masa Majapahit berdasarkan data yang ada, cukup berbeda dengan dengan bangunan hunian (rumah-rumah) dalam masa selanjutnya di Jawa. Perumahan di Jawa sesudah zaman Majapahit cenderung merupakan bangunan tertutup dengan sedikit bukaan untuk sirkulasi udara, adapun bangunan hunian masa Majapahit berupa bentuk arsitektur setengah terbuka, dan hanya sedikit yang tertutup untuk aktivitas pribadi penghuninya. Bangunan hunian mempunyai ciri antara lain (a) berdiri di permukaan batur yang relatif tinggi, (b) setiap bangunan memiliki beranda lebar, dan (c) jarak antar bangunan dalam gugusan Pakuwon telah tertata dengan baik. Agaknya orang-orang Majapahit telah menyadari bahwa bangunan huniannya harus tetap nyaman ditinggali walaupun berada di udara yang lebab dan panas matahari terus menerpa sepanjang tahun, dan kadang-kadang banjir juga memasuki permukiman. Bentuk bangunan hunian masa Majapahit, hingga awal abad ke-20 masih dapat dijumpai di Bali sebagai bangunan dengan arsitektur tradisional Bali. Akan tetapi dewasa ini bangunan tradisional tersebut telah langka di kota-kota besar Bali, begitupun di pedalamannya. -

Changing a Hindu Temple Into the Indrapuri Mosque in Aceh: the Beginning of Islamisation in Indonesia – a Vernacular Architectural Context

This paper is part of the Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art (IHA 2016) www.witconferences.com Changing a Hindu temple into the Indrapuri Mosque in Aceh: the beginning of Islamisation in Indonesia – a vernacular architectural context Alfan1 , D. Beynon1 & F. Marcello2 1Faculty of Science, Engineering and Built Environment, Deakin University, Australia 2Faculty of Health Arts and Design, Swinburne University, Australia Abstract This paper elucidates on the process of Islamisation in relation to vernacular architecture in Indonesia, from its beginning in Indonesia’s westernmost province of Aceh, analysing this process of Islamisation from two different perspectives. First, it reviews the human as the receiver of Islamic thought. Second, it discusses the importance of the building (mosque or Mushalla) as a human praying place that is influential in conducting Islamic thought and identity both politically and culturally. This paper provides evidence for the role of architecture in the process of Islamisation, by beginning with the functional shift of a Hindu temple located in Aceh and its conversion into the Indrapuri Mosque. The paper argues that the shape of the Indrapuri Mosque was critical to the process of Islamisation, being the compositional basis of several mosques in other areas of Indonesia as Islam developed. As a result, starting from Aceh but spreading throughout Indonesia, particularly to its Eastern parts, Indonesia’s vernacular architecture was developed by combining local identity with Islamic concepts. Keywords: mosque, vernacular architecture, human, Islamic identity, Islamisation. WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 159, © 2016 WIT Press www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3509 (on-line) doi:10.2495/IHA160081 86 Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art 1 Introduction Indonesia is an archipelago country, comprising big and small islands. -

Candi, Space and Landscape

Degroot Candi, Space and Landscape A study on the distribution, orientation and spatial Candi, Space and Landscape organization of Central Javanese temple remains Central Javanese temples were not built anywhere and anyhow. On the con- trary: their positions within the landscape and their architectural designs were determined by socio-cultural, religious and economic factors. This book ex- plores the correlations between temple distribution, natural surroundings and architectural design to understand how Central Javanese people structured Candi, Space and Landscape the space around them, and how the religious landscape thus created devel- oped. Besides questions related to territory and landscape, this book analyzes the structure of the built space and its possible relations with conceptualized space, showing the influence of imported Indian concepts, as well as their limits. Going off the beaten track, the present study explores the hundreds of small sites that scatter the landscape of Central Java. It is also one of very few stud- ies to apply the methods of spatial archaeology to Central Javanese temples and the first in almost one century to present a descriptive inventory of the remains of this region. ISBN 978-90-8890-039-6 Sidestone Sidestone Press Véronique Degroot ISBN: 978-90-8890-039-6 Bestelnummer: SSP55960001 69396557 9 789088 900396 Sidestone Press / RMV 3 8 Mededelingen van het Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden CANDI, SPACE AND LANDscAPE Sidestone Press Thesis submitted on the 6th of May 2009 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Leiden University. Supervisors: Prof. dr. B. Arps and Prof. dr. M.J. Klokke Referee: Prof. dr. J. Miksic Mededelingen van het Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde No. -

Perpaduan Budaya Lokal, Hindu Buddha, Dan Islam Di Indonesia

Diktat Bernuansa Karakter Mata Kuliah Sejarah Indonesia Masa Islam PERPADUAN BUDAYA LOKAL, HINDU BUDDHA, DAN ISLAM DI INDONESIA Oleh: M. Nur Rokhman, M. Pd PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL UNIVERSITAS NEGERI YOGYAKARTA 2014 0 KATA PENGANTAR Assalamu’alaikum wr. wb. Alkhamdulillah. Puji syukur kami panjatkan ke hadirat Alloh SWT atas segala rahmat dan hidayahNya, sehingga sekilas modul ini dapat diselesaikan. Modul ini bertemakan Perpaduan Budaya Lokal, Hindu Buddha dan Islam di Indonesia. Tema ini menarik untuk dikembangkan, mengingat perpaduan budaya lokal, Hindu Buddha dan Islam ada dalam kehidupan sehari-hari masyarakat Nusantara. Dengan demikian, tema ini akan sangat menarik untuk pembelajaran. Tema ini pun sangat kontekstual dengan kehidupan sehari-hari, sehingga para mahasiawa dapat menghayati, mengoservasi, bahkan wawancara materi yang dipelajarinya. Dengan tema ini pula para mahasiswa diharapkan dapat mengambil hikmah dan nilai-nilai karakter yang terkandung dalam materi yang dipelajarinya. Kami menyadari sepenuhnya bahwa modul sederhana ini dapat diselesaikan berkat uluran tangan, dorongan, bimbingan dan bantuan serta doa berbagai pihak. Untuk itu dengan setulus hati penulis mengucapkan terima kasih kepada; 1. Rektor Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta (UNY) yang telah memberikan kesempatan terselenggaranya pengembangan modul ini. 2. Ketua LPPMP UNY beserta staf yang telah memberikan pengetahuan dan kesempatan pengembangan modul ini. 3. Dekan beserta staf FIS UNY yang telah memberikan dorongan sehingga modul ini terselesaikan 1 4. Bapak Sardiman AM, M. Pd. Selaku Dosen Pembimbing senior yang telah memberikan arahan, dukungan dan bimbingan serta petunjuk yang sangat bermanfaat bagi penyelesaian modul ini 5. Semua pihak yang tidak dapat disebutkan satu persatu yang telah memberikan uluran tangan demi kelancaran penyusunan modul ini Teriring doa semoga amal dan budi baik mereka mendapat ridho dan berkah dari Alloh SWT.