Experimental Evaluation of the Importance of Colonization History in Early-Life Gut Microbiota Assembly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table S1. Nakharuthai and Srisapoome (2020)

Primer name Nucleotide sequence (5’→3’) Purpose CXC-1F New TGAACCCTGAGCTGAAGGCCGTGA Real-time PCR CXC-1R New TGAAGGTCTGATGAGTTTGTCGTC Real-time PCR CXC-1R CCTTCAGCTCAGGGTTCAAGC Genomic PCR CXC-2F New GCTTGAACCCCGAGCTGAAAAACG Real-time PCR CXC-2R New GTTCAGAGGTCGTATGAGGTGCTT Real-time PCR CXC-2F CAAGCAGGACAACAGTGTCTGTGT 3’RACE CXC-2AR GTTGCATGATTTGGATGCTGGGTAG 5’RACE CXC-1FSB AACATATGTCTCCCAGGCCCAACTCAAAC Southern blot CXC-1RSB CTCGAGTTATTTTGCACTGATGTGCAA Southern blot CXC1Exon1F CAAAGTGTTTCTGCTCCTGG Genomic PCR On-CXC1FOverEx CATATGCAACTCAAACAAGCAGGACAACAGT Overexpression On-CXC1ROverEx CTCGAGTTTTGCACTGATGTGCAATTTCAA Overexpression On-CXC2FOverEx CATATGCAACTCAAACAAGCAGGACAACAGT Overexpression On-CXC2ROverEx CTCGAGCATGGCAGCTGTGGAGGGTTCCAC Overexpression β-actinrealtimeF ACAGGATGCAGAAGGAGATCACAG Real-time PCR β-actinrealtimeR GTACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACAT Real-time PCR M13F AAAACGACGGCCAG Nucleotide sequencing M13R AACAGCTATGACCATG Nucleotide sequencing UPM-long (0.4 µM) CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT RACE PCR UPM-short (2 µM) CTAATAC GACTCACTATA GGGC RACE PCR Table S1. Nakharuthai and Srisapoome (2020) On-CXC1 Nucleotide (%) Amino acid (%) On-CXC2 Nucleotide (%) Amino acid (%) Versus identity identity similarity Versus identity identity Similarity Teleost fish 1. Rock bream, Oplegnathus fasciatus (AB703273) 64.5 49.1 68.1 O. fasciatus 70.7 57.7 75.4 2. Mandarin fish, Siniperca chuatsi (AAY79282) 63.2 48.1 68.9 S. chuatsi 70.5 54.0 78.8 3. Atlantic halibut, Hippoglossus hippoglossus (ACY54778) 52.0 39.3 51.1 H. hippoglossus 64.5 46.3 63.9 4. Common carp IL-8, Cyprinus carpio (ABE47600) 44.9 19.1 34.1 C. carpio 49.4 21.9 42.6 5. Rainbow trout IL-8, Oncorhynchus mykiss (CAC33585) 44.0 21.3 36.3 O. mykiss 47.3 23.7 44.4 6. Japanese flounder IL-8, Paralichthys olivaceus (AAL05442) 48.4 25.4 45.9 P. -

Mouse Models of Human Disease an Evolutionary Perspective Robert L

170 commentary Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health [2016] pp. 170–176 doi:10.1093/emph/eow014 Mouse models of human disease An evolutionary perspective Robert L. Perlman* Department of Pediatrics, The University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Ave, MC 5058, Chicago, IL 60637, USA *E-mail: [email protected] Received 31 December 2015; revised version accepted 12 April 2016 ABSTRACT The use of mice as model organisms to study human biology is predicated on the genetic and physio- logical similarities between the species. Nonetheless, mice and humans have evolved in and become adapted to different environments and so, despite their phylogenetic relatedness, they have become very different organisms. Mice often respond to experimental interventions in ways that differ strikingly from humans. Mice are invaluable for studying biological processes that have been conserved during the evolution of the rodent and primate lineages and for investigating the developmental mechanisms by which the conserved mammalian genome gives rise to a variety of different species. Mice are less reliable as models of human disease, however, because the networks linking genes to disease are likely to differ between the two species. The use of mice in biomedical research needs to take account of the evolved differences as well as the similarities between mice and humans. KEYWORDS: allometry; cancer; gene networks; life history; model organisms transgenic, knockout, and knockin mice, have If you have cancer and you are a mouse, we can provided added impetus and powerful tools for take good care of you. Judah Folkman [1] mouse research, and have led to a dramatic increase in the use of mice as model organisms. -

Micromys Minutus)

Acta Theriol (2013) 58:101–104 DOI 10.1007/s13364-012-0102-0 SHORT COMMUNICATION The origin of Swedish and Norwegian populations of the Eurasian harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) Lars Råberg & Jon Loman & Olof Hellgren & Jeroen van der Kooij & Kjell Isaksen & Roar Solheim Received: 7 May 2012 /Accepted: 17 September 2012 /Published online: 29 September 2012 # Mammal Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Białowieża, Poland 2012 Abstract The harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) occurs the Mediterranean, from France to Russia and northwards throughout most of continental Europe. There are also two to central Finland (Mitchell-Jones et al. 1999). Recently, isolated and recently discovered populations on the it has also been found to occur in Sweden and Norway. Scandinavian peninsula, in Sweden and Norway. Here, we In 1985, an isolated population was discovered in the investigate the origin of these populations through analyses province of Dalsland in western Sweden (Loman 1986), of mitochondrial DNA. We found that the two populations and during the last decade, this population has been on the Scandinavian peninsula have different mtDNA found to extend into the surrounding provinces as well haplotypes. A comparison of our haplotypes to published as into Norway. The known distribution in Norway is sequences from most of Europe showed that all Swedish and limited to a relatively small area close to the Swedish Norwegian haplotypes are most closely related to the border, in Eidskog, Hedmark (van der Kooij et al. 2001; haplotypes in harvest mice from Denmark. Hence, the two van der Kooij et al., unpublished data). In 2007, another populations seem to represent independent colonisations but population was discovered in the province of Skåne in originate from the same geographical area. -

A Guide to Mites

A GUIDE TO MITES concentrated in areas where clothes constrict the body, or MITES in areas like the armpits or under the breasts. These bites Mites are arachnids, belonging to the same group as can be extremely itchy and may cause emotional distress. ticks and spiders. Adult mites have eight legs and are Scratching the affected area may lead to secondary very small—sometimes microscopic—in size. They are bacterial infections. Rat and bird mites are very small, a very diverse group of arthropods that can be found in approximately the size of the period at the end of this just about any habitat. Mites are scavengers, predators, sentence. They are quite active and will enter the living or parasites of plants, insects and animals. Some mites areas of a home when their hosts (rats or birds) have left can transmit diseases, cause agricultural losses, affect or have died. Heavy infestations may cause some mites honeybee colonies, or cause dermatitis and allergies in to search for additional blood meals. Unfed females may humans. Although mites such as mold mites go unnoticed live ten days or more after rats have been eliminated. In and have no direct effect on humans, they can become a this area, tropical rat mites are normally associated with nuisance due to their large numbers. Other mites known the roof rat (Rattus rattus), but are also occasionally found to cause a red itchy rash (known as contact dermatitis) on the Norway rat, (R. norvegicus) and house mouse (Mus include a variety of grain and mold mites. Some species musculus). -

Modulation of the Gut Microbiota Alters the Tumour-Suppressive Efficacy of Tim-3 Pathway Blockade in a Bacterial Species- and Host Factor-Dependent Manner

microorganisms Article Modulation of the Gut Microbiota Alters the Tumour-Suppressive Efficacy of Tim-3 Pathway Blockade in a Bacterial Species- and Host Factor-Dependent Manner Bokyoung Lee 1,2, Jieun Lee 1,2, Min-Yeong Woo 1,2, Mi Jin Lee 1, Ho-Joon Shin 1,2, Kyongmin Kim 1,2 and Sun Park 1,2,* 1 Department of Microbiology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Youngtongku Wonchondong San 5, Suwon 442-749, Korea; [email protected] (B.L.); [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (M.-Y.W.); [email protected] (M.J.L.); [email protected] (H.-J.S.); [email protected] (K.K.) 2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, The Graduate School, Ajou University, Youngtongku Wonchondong San 5, Suwon 442-749, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-31-219-5070 Received: 22 August 2020; Accepted: 9 September 2020; Published: 11 September 2020 Abstract: T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein-3 (Tim-3) is an immune checkpoint molecule and a target for anti-cancer therapy. In this study, we examined whether gut microbiota manipulation altered the anti-tumour efficacy of Tim-3 blockade. The gut microbiota of mice was manipulated through the administration of antibiotics and oral gavage of bacteria. Alterations in the gut microbiome were analysed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Gut dysbiosis triggered by antibiotics attenuated the anti-tumour efficacy of Tim-3 blockade in both C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice. Anti-tumour efficacy was restored following oral gavage of faecal bacteria even as antibiotic administration continued. In the case of oral gavage of Enterococcus hirae or Lactobacillus johnsonii, transferred bacterial species and host mouse strain were critical determinants of the anti-tumour efficacy of Tim-3 blockade. -

A Phylogeographic Survey of the Pygmy Mouse Mus Minutoides in South Africa: Taxonomic and Karyotypic Inference from Cytochrome B Sequences of Museum Specimens

A Phylogeographic Survey of the Pygmy Mouse Mus minutoides in South Africa: Taxonomic and Karyotypic Inference from Cytochrome b Sequences of Museum Specimens Pascale Chevret1*, Terence J. Robinson2, Julie Perez3, Fre´de´ric Veyrunes3, Janice Britton-Davidian3 1 Laboratoire de Biome´trie et Biologie Evolutive, UMR CNRS 5558, Universite´ Lyon 1, Villeurbanne, France, 2 Evolutionary Genomics Group, Department of Botany and Zoology, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 3 Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution de Montpellier, UMR CNRS 5554, Universite´ Montpellier 2, Montpellier, France Abstract The African pygmy mice (Mus, subgenus Nannomys) are a group of small-sized rodents that occur widely throughout sub- Saharan Africa. Chromosomal diversity within this group is extensive and numerous studies have shown the karyotype to be a useful taxonomic marker. This is pertinent to Mus minutoides populations in South Africa where two different cytotypes (2n = 34, 2n = 18) and a modification of the sex determination system (due to the presence of a Y chromosome in some females) have been recorded. This chromosomal diversity is mirrored by mitochondrial DNA sequences that unambiguously discriminate among the various pygmy mouse species and, importantly, the different M. minutoides cytotypes. However, the geographic delimitation and taxonomy of pygmy mice populations in South Africa is poorly understood. To address this, tissue samples of M. minutoides were taken and analysed from specimens housed in six South African museum collections. Partial cytochrome b sequences (400 pb) were successfully amplified from 44% of the 154 samples processed. Two species were identified: M. indutus and M. minutoides. The sequences of the M. indutus samples provided two unexpected features: i) nuclear copies of the cytochrome b gene were detected in many specimens, and ii) the range of this species was found to extend considerably further south than is presently understood. -

Rats and Mice Have Always Posed a Threat to Human Health

Rats and mice have always posed a threat to human health. Not only do they spread disease but they also cause serious damage to human food and animal feed as well as to buildings, insulation material and electricity cabling. Rats and mice - unwanted house guests! RATS AND MICE ARE AGILE MAMMALS. A mouse can get through a small, 6-7 mm hole (about the diameter of a normal-sized pen) and a rat can get through a 20 mm hole. They can also jump several decimetres at a time. They have no problem climbing up the inside of a vertical sewage pipe and can fall several metres without injuring themselves. Rats are also good swimmers and can be underwater for 5 minutes. IN SWEDEN THERE ARE BASICALLY four different types of rodent that affect us as humans and our housing: the brown rat, the house mouse and the small and large field mouse. THE BROWN RAT (RATTUS NORVEGICUS) THRIVES in all human environments, and especially in damp environments like cellars and sewers. The brown rat is between 20-30 cm in length not counting its tail, which is about 15-23 cm long. These rats normally have brown backs and grey underbellies, but there are also darker ones. They are primarily nocturnal, often keep together in large family groups and dig and gnaw out extensive tunnel systems. Inside these systems, they build large chambers where they store food and build their nests. A pair of rats can produce between 800 and 1000 offspring a year. Since their young are sexually mature and can have offspring of their own at just 2-4 months old, rats reproduce extraordinarily quickly. -

Table of Contents I

Comparison of the gut microbiome of a generalist insect, Spodoptera littoralis and a specialist, leaf and root feeder one, Melolontha hippocastani Dissertation To Fulfill the Requirements for the Degree of „doctor rerum naturalium“ (Dr. rer. nat.) Submitted to the Council of the Faculty Of Biology and Pharmacy of the Friedrich Schiller University By Master of Science of Horticulture Erika Arias Cordero Born on 01.11.1977 in San José, Costa Rica Gutachter: 1. ___________________________ 2. ___________________________ 3. ___________________________ Tag der öffentlichen verteidigung:……………………………………. Table of Contents i Table of Contents 1. General Introduction 1 1.1 Insect-bacteria associations ......................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Intracellular endosymbiotic associations ........................................................... 2 1.1.2 Exoskeleton-ectosymbiotic associations ........................................................... 4 1.1.3 Gut lining ectosymbiotic symbiosis ................................................................... 4 1.2 Description of the insect species ................................................................................ 12 1.2.1 Biology of Spodoptera littoralis ............................................................................ 12 1.2.2 Biology of Melolontha hippocastani, the forest cockchafer ................................... 14 1.3 Goals of this study .................................................................................................... -

Mice Are Here to Stay

Mice A re Here to Stay Wherever people live, there are mice. It would be difficult to find another animal that has adapted to the habitats created by humans as well as the house mouse has. It thus seemed obvious to Diethard Tautz at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Plön that the species would make an ideal model system for investigating how evolution works. BIOLOGY & MEDICINE_Evolution Mice A re Here to Stay TEXT CORNELIA STOLZE he mice at the Max Planck mice themselves only within a range of can be a key factor in the emergence of Institute in Plön live in their 30 to 50 centimeters, they convey high- new species. For Tautz, the house very own house: they have ly complex messages. mouse is a model for the processes of 16 rooms where they can Diethard Tautz and his colleagues evolution: it would be difficult to find form their family clans and have discovered that house mice be- another animal species that lends itself T territories as they see fit. The experi- have naturally only when they live in so well to the study of the genetic ments Tautz and his colleagues carry a familiar environment and interact mechanisms of evolution. out to study such facets as the rodents’ with other members of their species. “Not only is this species extremely communication, behavior and partner- When animals living in the wild are adaptable, as demonstrated by its dis- ships sometimes take months. During captured, they lose their familiar envi- persal all over the globe, but we also this time, the mice are largely left to ronment: everything smells and tastes know its genome better than that of al- their own devices. -

Impact Du Régime Alimentaire Sur La Dynamique Structurale Et Fonctionnelle Du Microbiote Intestinal Humain Julien Tap

Impact du régime alimentaire sur la dynamique structurale et fonctionnelle du microbiote intestinal humain Julien Tap To cite this version: Julien Tap. Impact du régime alimentaire sur la dynamique structurale et fonctionnelle du microbiote intestinal humain. Microbiologie et Parasitologie. Université Pierre et Marie Curie - Paris 6, 2009. Français. tel-02824828 HAL Id: tel-02824828 https://hal.inrae.fr/tel-02824828 Submitted on 6 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PIERRE ET MARIE CURIE Spécialité Physiologie et physiopathologie Présentée par M. Julien Tap Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR de l’UNIVERSITÉ PIERRE ET MARIE CURIE Sujet de la thèse : Impact du régime alimentaire sur la dynamique structurale et fonctionnelle du microbiote intestinal humain soutenue le 16 décembre 2009 devant le jury composé de : M. Philippe LEBARON, Président du jury Mme Karine CLEMENT, Examinateur Mme Annick BERNALIER, Rapporteur Mme Gabrielle POTOCKI-VERONESE, Examinateur M. Jean FIORAMONTI, Rapporteur M. Eric PELLETIER, Examinateur Mme Marion LECLERC, Examinateur Université Pierre & Marie Curie - Paris 6 Tél. Secrétariat : 01 42 34 68 35 Bureau d’accueil, inscription des doctorants et base de Fax : 01 42 34 68 40 données Tél. -

APPENDIX K: Accepted ECOTOX Data Table

APPENDIX K: Accepted ECOTOX Data Table The code list for ECOTOX can be found at: http://cfpub.epa.gov/ecotox/blackbox/help/codelist.pdf CAS Number Chemical Name Genus Species Common Name Effect Group Effect Meas Endpt1 Endpt2 Dur Preferred Conc Value1 Preferred Conc Value2 Preferred Conc Units Preferred % Purity Ref # 330541 Diuron Pimephales promelas Fathead minnow ACC ACC GACC BCF 1 TO 24 0.00315 TO 0.0304 mg/L 100 12612 330541 Diuron Rattus norvegicus Norway rat BCM BCM PHPH NOAEL 140 2500 ppm 100 90555 330541 Diuron Zostera capricorni Eelgrass BCM BCM FLRS LOAEL 8.33E-02 0.01 mg/L 100 72996 330541 Diuron Zostera capricorni Eelgrass BCM BCM FLRS LOAEL 8.33E-02 0.01 mg/L 100 72996 330541 Diuron Zostera capricorni Eelgrass BCM BCM FLRS LOAEL 8.33E-02 0.01 mg/L 100 72996 330541 Diuron Seriatopora hystrix Coral BCM BCM FLRS NOEC LOEC 0.416666667 0.0003 0.0003 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Seriatopora hystrix Coral BCM BCM FLRS EC25 0.416666667 0.00085 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Seriatopora hystrix Coral BCM BCM FLRS EC50 0.416666667 0.0023 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Acropora formosa Stony coral BCM BCM FLRS NOEC LOEC 1 0.00003 0.0003 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Acropora formosa Stony coral BCM BCM FLRS EC25 1 0.0012 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Acropora formosa Stony coral BCM BCM FLRS EC50 1 0.0027 mg/L 100 75334 330541 Diuron Synechococcus sp. Blue-green algae BCM BCM CHCT NOAEL 3 0.0033 mg/L 99 98904 330541 Diuron Lemna minor Duckweed BCM BCM GLTH LOAEL 2 0.02475 mg/L >99 64164 330541 Diuron Scenedesmus acutus Green Algae BCM BCM -

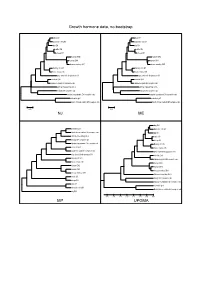

Growth Hormone Data, No Bootstrap NJ ME MP UPGMA

Growth hormone data, no bootstrap dog GH dog GH domestic cat GH domestic cat GH pig GH pig GH cattle GH cattle GH sheep GH sheep GH human GH2 human GH2 human GH1 human GH1 rhesus monkey GH1 rhesus monkey GH1 Norway rat Gh1 Norway rat Gh1 house mouse Gh house mouse Gh gray short-tailed opossum GH gray short-tailed opossum GH chicken GH1 chicken GH1 Japanese quail GH complete cds Japanese quail GH complete cds African clawed frog Gh A African clawed frog Gh A beluga GH complete cds beluga GH complete cds banded houndshark GH complete cds banded houndshark GH complete cds zebrafish gh1 zebrafish gh1 North African catfish GH complete cds North African catfish GH complete cds 0.05 0.05 NJ ME dog GH zebrafish gh1 domestic cat GH North African catfish GH complete cds pig GH African clawed frog Gh A cattle GH beluga GH complete cds sheep GH banded houndshark GH complete cds Norway rat Gh1 chicken GH1 house mouse Gh Japanese quail GH complete cds gray short-tailed opossum GH gray short-tailed opossum GH chicken GH1 Norway rat Gh1 Japanese quail GH complete cds house mouse Gh human GH2 human GH2 human GH1 human GH1 rhesus monkey GH1 rhesus monkey GH1 African clawed frog Gh A cattle GH beluga GH complete cds sheep GH banded houndshark GH complete cds dog GH zebrafish gh1 domestic cat GH North African catfish GH complete cds pig GH 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.20 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00 MP UPGMA Growth hormone data, 1000x bootstrapping 96 dog GH 95 dog GH 85 domestic cat GH 93 domestic cat GH 79 pig GH 81 pig GH cattle GH cattle GH 92 77 100 sheep GH 100 sheep GH