The Importance of Considering 'Setting' in a Heritage Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey Report

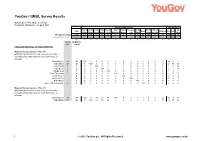

YouGov / QMUL Survey Results Sample Size: 1048 adults in London Fieldwork: 16th - 19th November 2020 Mayoral Voting Intention Vote in 2019 GE Shaun Sadiq Luisa Siân Mandu Peter Don’t Would Lib Total Other Refused Con Lab Bailey Khan Porritt Berry Reid Gammons know not vote Dem Weighted Sample 1048 183 324 31 60 9 12 16 260 92 60 254 381 118 Unweighted Sample 1048 190 341 33 70 11 15 18 253 69 48 259 392 112 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % 2-6 16-19 Mar Nov HEADLINE MAYORAL VOTING INTENTION Mayoral Voting Intention - Round 1 [Weighted by likelihood to vote in mayoral election, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Shaun Bailey 24 30 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 81 2 15 Sadiq Khan 49 51 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 81 56 Luisa Porritt - 4 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 20 Siân Berry 7 9 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 12 7 Mandu Reid 1 1 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 3 Peter Gammons - 2 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 5 0 0 Some other candidate 3 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 2 1 0 Mayoral Voting Intention - Round 2 [Weighted by likelihood to vote in mayoral election, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Shaun Bailey 33 36 100 0 23 6 30 100 0 0 0 48 91 3 18 Sadiq Khan 67 64 0 100 77 94 70 0 100 0 0 52 9 97 82 1 © 2020 YouGov plc. -

Adults Resident London Methodology

Agency: Panelbase Universe: Adults resident London Methodology: Online Sample size: 1002 Fieldwork dates: 4 - 5 May 2021 Weighting: All the results were weighted by age, sex, region and 2019 Westminster election Further enquiries: [email protected] JN:W16599l London Poll Base: 1,002 Total GenderXAge_2 2019 Westminster Westminster Voting Intention 2016 EU Referendum Male x 18- Male x 35- Male x 55+ Female x Female x Female x CON LAB Lib Dem CON LAB Lib Dem Remain Leave Did not 34 54 18-34 35-54 55 vote Total 1002 172 191 133 168 185 151 274 412 128 237 397 95 502 336 164 (1002) (180) (199) (128) (179) (189) (126) (320) (360) (118) (267) (367) (92) (537) (301) (164) Q3. Who would you vote for?... Base: Likely voters 774 125 154 123 115 128 129 240 340 113 219 328 84 414 283 77 Likely voters (771) (130) (161) (117) (120) (134) (108) (277) (296) (103) (244) (301) (80) (438) (257) (76) Labour 328 64 62 32 64 61 42 16 276 15 0 328 0 233 60 34 42% 51% 41% 26% 56% 48% 33% 7% 81% 13% 0 100% 0 56% 21% 44% Conservative 219 23 52 54 18 30 43 194 13 4 219 0 0 54 147 18 28% 18% 34% 44% 16% 23% 34% 81% 4% 4% 100% 0 0 13% 52% 24% Liberal Democrats 84 14 20 12 10 14 13 6 6 66 0 0 84 58 17 9 11% 11% 13% 10% 9% 11% 10% 3% 2% 59% 0 0 100% 14% 6% 11% Green 39 9 2 6 9 7 6 2 11 5 0 0 0 28 9 2 5% 7% 1% 5% 8% 5% 5% <1% 3% 5% 0 0 0 7% 3% 2% Other 25 6 5 6 1 5 1 5 5 3 0 0 0 4 21 0 3% 5% 3% 5% 1% 4% 1% 2% 1% 3% 0 0 0 <1% 7% 0 Would not vote 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 <1% 0 0 0 <1% 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 <1% 0 0 Don’t Know/ Not sure 70 7 11 12 8 10 21 17 25 17 0 0 0 31 28 12 9% 6% 7% 10% 7% 8% 17% 7% 7% 15% 0 0 0 7% 10% 15% Prefer not to say 10 2 2 0 3 2 1 1 3 2 0 0 0 7 0 3 1% 2% 1% 0 2% 2% 1% <1% <1% 2% 0 0 0 2% 0 4% Q3. -

Vote Good Food 2021 Report

Vote Good Food A London Food Link report on the London Mayoral Election 2021 GOOD VOTE FOOD 2 Vote Good Food London Food Link London Food Link is part of the charity Sustain: the alliance for better food and farming. We bring together people who grow, make, cook, sell and eat good food in the capital to help create a healthy and sustainable food system for all. We run and support policy initiatives, campaigns, and practical projects to improve the food system. We also provide information, events, and advice for our supporters, who include food producers, retailers, policy makers and citizens in London. This report was created by London Food Link and supported by the Food Foundation, Feedback and the Orchard Project. www.londonfoodlink.org Did you know you can join London Food Link? Show your support for our campaigns and initiatives, as we work and campaign for a healthy and sustainable food system for all Londoners. Vote Good Food 3 London elections 2021 London Food Link: In recent years, London has made great strides our actions to date in promoting healthy and sustainable food, and while great progress has been made in many London Food Link has taken several actions to areas, the last mayoral term faced new challenges, put food on the agenda of the mayoral candidates compounded by the Covid-19 pandemic where during this campaign including: the importance of food was recognised across our • Working with partner organisations to produce city. a manifesto of our top asks for the mayoral London’s next Mayor will be elected on the 6 May candidates. -

Survey Report

YouGov / QMUL Survey Results Sample Size: 1192 adults in London Fieldwork: 29th March - 1st April 2021 Mayoral Voting Intention Westminster VI Shaun Sadiq Luisa Siân Mandu Peter David Laurence Brian Don’t Would Lib Total Other Refused Con Lab Bailey Khan Porritt Berry Reid Gammons Kurten Fox Rose know not vote Dem Weighted Sample 1192 201 378 58 74 11 9 1 34 26 15 258 71 56 257 415 68 Unweighted Sample 1192 192 429 53 84 16 7 2 34 18 17 241 53 46 236 469 73 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % 16-19 29 March- Nov 1 April HEADLINE MAYORAL VOTING INTENTION Mayoral Voting Intention - Round 1 [Weighted by likelihood to vote in mayoral election, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Shaun Bailey 30 26 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 76 3 1 Sadiq Khan 51 47 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 83 39 Luisa Porritt 4 7 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 5 36 Siân Berry 9 9 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 7 14 Mandu Reid 1 1 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 4 Peter Gammons 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 David Kurten - 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Laurence Fox - 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 8 0 7 Brian Rose - 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 2 2 0 Some other candidate 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 2 0 0 Mayoral Voting Intention - Round 2 [Weighted by likelihood to vote in mayoral election, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Shaun Bailey 36 34 100 0 14 12 40 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 59 91 3 10 Sadiq Khan 64 66 0 100 86 88 60 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 41 9 97 90 1 © 2021 YouGov plc. -

For Mayor of London Luisa Porritt

Luisa Porritt’s plan to... TAKE LONDON Luisa Porritt FORWARD For Mayor of London BACK LOCAL BUSINESS Luisa demands urgent action on jobs Luisa Porritt has demanded urgent action from the Government to provide businesses with the support they need. The Liberal Democrat Mayoral candidate has been listening to local businesses that have been hit hard by the impact of Covid-19. She has called for business rates relief to be extended and for more financial help for workers who have been left out Lib Dem Mayoral candidate, Luisa Porritt (centre), and London Assembly candidates, Hina Bokhari (left) and Claire of the furlough scheme. Bonham (right), have a plan to reinvent the high street The challenger to Sadiq Khan also has big ideas for London’s recovery. Luisa’s plan includes investment to “We need shared working spaces, more reinvent local high streets. She said: places to eat, drink and shop, and other local services like childcare.” “We can reinvent “Investing in London’s high streets will kickstart our city’s recovery, creating “Under my leadership, we can reinvent our high streets” local jobs and revitalising the heart of our high streets so they are fit for the our communities. future.” LUISA: HOPE IS ON THE HORIZON As the impact of Covid-19 takes its toll on Londoners, the vaccine rollout and a chance to reshape our city for the better gives us hope By Luisa Porritt, Liberal Democrat We worry about problems that existed candidate for Mayor of London before this crisis, such as how hard it is to live in an expensive city like London and It’s been an incredibly tough time. -

Survey Report

YouGov Survey Results Sample Size: 1141 adults in London Fieldwork: 2nd - 4th May 2021 Mayoral Voting Intention Westminster VI Shaun Sadiq Luisa Siân Mandu Peter David Laurence Brian Don’t Would Lib Total Other Refused Con Lab Bailey Khan Porritt Berry Reid Gammons Kurten Fox Rose know not vote Dem Weighted Sample 1141 241 336 39 78 8 11 5 19 18 32 174 120 59 262 415 55 Unweighted Sample 1141 234 349 40 80 9 9 5 22 14 31 179 117 52 264 415 63 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % 29 March- 2-4 1 April May HEADLINE MAYORAL VOTING INTENTION Mayoral Voting Intention - Round 1 [Weighted by likelihood to vote in mayoral election, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Shaun Bailey 26 31 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 84 6 5 Sadiq Khan 47 43 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 77 43 Luisa Porritt 7 5 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 3 38 Siân Berry 9 10 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 8 6 Mandu Reid 1 1 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Peter Gammons 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 David Kurten 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 Laurence Fox 4 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 Brian Rose 3 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 1 2 1 Some other candidate 2 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 1 2 5 Mayoral Voting Intention - Round 2 [Weighted by likelihood to vote in mayoral election, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Shaun Bailey 34 41 100 0 37 11 56 72 0 100 65 21 0 0 70 95 8 13 Sadiq Khan 66 59 0 100 63 89 44 28 0 0 35 79 0 0 30 5 92 87 1 © 2021 YouGov plc. -

London Forum Insights

Roundcube Webmail :: London Forum Insights http://webmail.brentfordcc.org.uk/cpsess3120125005/3rdparty/roundcu... View this email in your browser Issue 4, April 2021 Welcome to another heavyweight issue of London Forum Insights, due in part to the stream of announcements and consultations from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG)*. We report on the Zoom meeting with members following the publication of the draft National Model Design Code (NMDC) and proposed changes to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), and summarise London Forum's response to the consultation. We also report on the Government's unwelcome (at least for London Forum members) decision not to allow online planning committee meetings to continue, followed almost immediately by steps to negate this decision. Even this odd turn of events was trumped by the announcement that the Government is pressing ahead with its widely deplored intention to introduce a Permitted Development Right (PDR) for the conversion of almost all most business and commercial buildings to residential. The upcoming mayoral election is the subject of three contributions. London Forum's new President, Ben Derbyshire presents a wish list for the next mayoral term on behalf of the Built Environment professions, Andrew Bosi looks at the electoral process by which the winner will emerge, and Daniel Instone compares candidates' pronouncements for improving the environment. We carry a contributed article from Gordon Massey, Barnet Residents Association on suburban densification and the threat to the suburbs arising from the Small Sites policy in the recently adopted London Plan – responses welcome! A planned Zoom meeting to explore this topic had to be postponed as the GLA team are in purdah ahead of the 1 of 13 16/04/2021, 14:13 Roundcube Webmail :: London Forum Insights http://webmail.brentfordcc.org.uk/cpsess3120125005/3rdparty/roundcu.. -

Liberal Democrat Alternative Budget Proposals 2021

Liberal Democrats Budget Amendments 2021/22 1 Liberal Democrats Budget Amendments 2021/22 Putting residents’ priorities at the heart of Camden’s recovery Introduction The past year has been incredibly difficult for communities in Camden and beyond. Residents have lost family, friends and neighbours to the Covid-19 pandemic, and the associated economic crisis is causing a sharp rise in unemployment. The number of people claiming out of work benefits in Camden rose by 162% between the first lockdown and November 2020, from over 4,000 residents to more than 11,000,1 a snapshot of the financial hardship now facing so many. Unemployment is rising fastest among 16- to 24-year-olds, risking a lost generation, despite Government schemes intended to prevent this. 2 There were already serious challenges facing our borough before the pandemic, and the scale of the public health and economic crises that have emerged over the past year have only exacerbated these. From the climate emergency to the Conservative Government’s disastrous Brexit deal (regrettably supported by Camden Labour MPs), to youth violence, rising unemployment, homelessness, and food poverty, for many the concept of ‘recovery’ will feel remote - even once a large section of the population has been vaccinated and, hopefully, the economy begins to open up again. This is especially true for the families and individuals across Camden pushed into relative poverty for the first time over the past year, and the children and young people whose futures have been put at risk by severe disruption to their education and employability. At this critical moment, it is vital that the Council steps up to address the borough’s most urgent challenges and alleviate their impact on Camden residents. -

Solidarity 583

Solidarity& Workers’ Liberty For social ownership of the banks and industry DROP CHARGES AGAINST HONG See page 2 Myanmar:KONG general What Russia’s REBELS Fight “business”, The great post strike strike against coup socialists are saying don’t partner with it of 1971 Workers central to the Rett Perera reports Keir Starmer’s attempt at How 200,000 post and fight back, despite heavy from Moscow on the an anti-Tory profile is a telecom workers struck for repression. movement against Putin. flop. 44 days, by Dave Chapple Page 3 Pages 7-8 Page 11 Pages 12-13 No. 583, 24 February 2020 50p/£1 workersliberty.org Drop charges against HK rebels! Editorial n 16 February, the trial started of seven democracy Oleaders in Hong Kong. Two others pleaded guilty. They are accused of organising an unauthorised assem- bly on 18 August 2019, when the Civil Front called a rally of 1.7 million people. Among the accused are Hong Kong trade union leader Lee Cheuk Yan, General Secretary of the HKCTU (Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions); other left wing activists such as Leung Kwok Hung (“Long Hair”); and For now, China’s police-state union, the All China Feder- “pan-democratic” veterans such as the 82 year old Martin ation of Trade Unions, is welcomed at some international Lee. union gatherings. In the Morning Star, HK protests for de- The charges, unconnected with the new National Secu- mocracy have been denounced as riots, and evidence of rity Law (NSL) and relying instead on old British colonial forced labour of Uyghurs denied. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Tuesday Volume 693 27 April 2021 No. 207 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 27 April 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 215 27 APRIL 2021 216 Alan Brown: The reality is that the powers of the House of Commons Scottish Government are not adequate to deal with the pandemic. There are too many constraints on borrowing powers for the Scottish Government; the reality is that Tuesday 27 April 2021 councils can borrow more easily under the prudential borrowing code. Does the Minister not agree that it is The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock time the Scottish Government had more flexible borrowing powers? PRAYERS Steve Barclay: The Smith commission set out the conditions, and they already give substantial borrowing [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] powers. That is why there is up to £450 million of Virtual participation in proceedings commenced (Orders, annual capital borrowing, £700 million in the Scotland 4 June and 30 December 2020). reserve and up to £600 million for resource borrowing [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] in relation to forecast error, and of course that comes on top of the share of UK Government borrowing provided through the Barnett formula. Oral Answers to Questions Living Standards Drew Hendry (Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and TREASURY Strathspey) (SNP): What recent assessment he has made of the effect of his policies on living standards. [914811] The Chancellor of the Exchequer was asked— John Nicolson (Ochil and South Perthshire) (SNP): Levelling-Up Fund What recent assessment he has made of the effect of his policies on living standards. -

Have No Symptoms Protect Your Loved Ones

Friday 30th April 2021 @hounslowherald @hounslowherald hounslowherald.co.uk Got a story? call: 020 3623 0567 [email protected] Now taking registrations T: 020 8995 9538 E: [email protected] NEWS Mayor and Housing Secretary urged to reject plans for Osterley Isleworth hit and Tower blocks run: Police appeal Page 05 NEWS Council accused of causing 'destruction to wildlife' in Boston after man killed Manor Park London Two people have been arrested following a fatal hit and run in Isleworth on Wednesday 28th April. Police were called to Page 04 the A4, junction with Thornbury Road at 21:16, NEWS following reports of a Hounslow free food distribution collision between a car charity launches summer appeal and pedestrian. Áine McGinty [email protected] efforts of the emergency services he of causing death by dangerous driving Serious Collision Investigation Unit fficers and the London Am- sadly died at the scene. - both remain in custody. on: 020 8543 5157. bulance Service attended The car did not stop at the scene but Anyone who saw the collision who You can also call 101 quoting: and found the pedestrian, was subsequently located and two peo- has not yet spoken to officers, or who CAD 7527/28Apr or tweet @ a man believed to be in his ple, a 39-year-old woman and a 37-year- has dashcam footage which may assist MetCC. O50s, suffering injuries. Despite the best old man, were arrested on suspicion the investigation, is asked to call the Page 10 Approximately 1 in 3 people with COVID-19 You could be spreading it without realising it. -

UK Election Statistics: 1918- 2021: a Century of Elections

By Sam Pilling, RIchard Cracknell UK Election Statistics: 1918- 18 August 2021 2021: A Century of Elections 1 Introduction 2 General elections since 1918 3 House of Commons by-elections 4 European Parliament elections (UK) 5 Elections to devolved legislatures and London elections 6 Local Elections 7 Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) Elections 8 Referendums 9 Appendix A: Voting systems and electoral geographies used in the UK elections commonslibrary.parliament.uk Number CBP7529 UK Election Statistics: 1918-2021: A Century of Elections Image Credits Autumn colours at Westminster by Manish Prabhune. Licensed by CC BY 2.0 / image cropped. Disclaimer The Commons Library does not intend the information in our research publications and briefings to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. We have published it to support the work of MPs. You should not rely upon it as legal or professional advice, or as a substitute for it. We do not accept any liability whatsoever for any errors, omissions or misstatements contained herein. You should consult a suitably qualified professional if you require specific advice or information. Read our briefing ‘Legal help: where to go and how to pay’ for further information about sources of legal advice and help. This information is provided subject to the conditions of the Open Parliament Licence. Feedback Every effort is made to ensure that the information contained in these publicly available briefings is correct at the time of publication. Readers should be aware however that briefings are not necessarily updated to reflect subsequent changes. If you have any comments on our briefings please email [email protected].