Kingsley Amis, Saul Bellow, Franz Kafka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Fiction Today

Birkbeck ePrints: an open access repository of the research output of Birkbeck College http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. In Rod Mengham and Philip Tew eds. British Fiction Today. London/New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., pp.3-14. This is an author-produced version of a paper published in British Fiction Today (ISBN 0826487319). This version has been peer-reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof corrections, published layout or pagination. All articles available through Birkbeck ePrints are protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Citation for this version: Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. London: Birkbeck ePrints. Available at: http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/archive/00000437 Citation for the publisher’s version: Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. In Rod Mengham and Philip Tew eds. British Fiction Today. London/New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., pp.3-14. http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk Contact Birkbeck ePrints at [email protected] The Middle Years of Martin Amis Joseph Brooker Martin Amis (b.1949) was a fancied newcomer in the 1970s and a defining voice in the 1980s. He entered the 1990s as a leading player in British fiction; by his early forties, the young talent had grown into a dominant force. Following his debut The Rachel Papers (1973), he subsidised his fictional output through the 1970s with journalistic work, notably as literary editor at the New Statesman. -

Discussion Guide

ROSENBERG LIBRARY Additional Resources: This program, slideshow, and links below can be PROGRAM AGENDA found at Rosenberg Library www.rosenberg-library.org Spring 2015 April 8 · May 21 For additional web resources, please visit: 12:00 noon Welcome & Introductions http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2014/07/goldfinch-donna-tartt- 12:00-12:20 Screening of Author Interview literary-criticism 12:20-1:00 Book Discussion http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/moviesnow/la-et- mn-donna-tartt-goldfinch-warner-bros-pulitzer-20140728-story.html http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/carel-fabritius AUTHOR BIO Born in 1963, novelist Donna Tartt grew up in the small town of Grenada, Mississippi. Her love of literature was evident at an early age, with her first sonnet published at age thirteen. She enrolled the University of Mississippi in 1981, and made an immediate impression on her professors. Recognizing her talent, they encouraged her to transfer to the writing program at Bennington College, a liberal arts school in Vermont. It was there that she began writing her first novel, The Secret History. The book was published in 1992 and became an overnight sensation, making Tartt a literary celebrity at just 28 years old. Her second novel, The Little Friend, was published in 2002, and it too received critical acclaim. Tartt’s much-anticipated, 800- Rosenberg Library’s page third work, The Goldfinch, was released in 2013. It Museum Book Club provides a forum for received the 2013 National Book Critics Circle Award, the 2014 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, and the discovery and discussion, linking literary 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. -

PDF Download Further Requirements: Interviews

FURTHER REQUIREMENTS: INTERVIEWS, BROADCASTS, STATEMENTS AND REVIEWS, 1952-85 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Philip Larkin,Anthony Thwaite | 416 pages | 04 Nov 2002 | FABER & FABER | 9780571216147 | English | London, United Kingdom Further Requirements: Interviews, Broadcasts, Statements and Reviews, 1952-85 PDF Book When you have read it, take me by the hand As children do, loving simplicity. Shopbop Designer Modemarken. In Thwaite's poems there is rarely much in the way of display and few extravagant local effects. Geben Sie Feedback zu dieser Seite. Andere Formate: Gebundenes Buch , Taschenbuch. Cookies akzeptieren Cookie-Einstellungen anpassen. Thwaite is also an accomplished comic poet. Author statement 'If I could sum up my poetry in a few well-chosen words, the result might be a poem. Entdecken Sie jetzt alle Amazon Prime-Vorteile. Poetry and What is Real. Philip Larkin remains England's best-loved poet - a writer matchlessly capable of evoking his native land and of touching all readers from the most sophisticated intellectual to the proverbial common reader. Etwas ist schiefgegangen. Next page. Weitere Informationen bei Author Central. Philip Larkin. Anthony Thwaite. While Larkin views them in terms of the personal life, or at most, of England, Thwaite, who has travelled widely and worked overseas for extended periods, can also find them in an alien setting, for example in North Africa. Previous page. Artists, cultural professionals and art collective members in the UK and Southeast A… 1 days ago. Sind Sie ein Autor? Urbane, weary, aphoristic, certain that nothing and everything changes, the poems draw both on Cavafy and Lawrence Durrell. This entirely new edition brings together all of Philip Larkin's poems. -

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

Post Nuclear Apocalyptic Vision in Martin Amis's Einstein's Monsters

Post Nuclear Apocalyptic Vision in Martin Amis’s Einstein’s Monsters The research paper aims to analyze the study of Martin Amis’s Einstein’s Monsters in order to exhibit the philosophical concept of dystopia or anti-utopia. With the abundant evidences from stories and an essay which are collected in Einstein’s Monsters, the researcher comes to find out that utopia cannot be maintained by Europeans due to several reasons, for instance, proliferation of nuclear nukes, unchecked flourishments of industrialization, sense of egotism, escalation of science and technology and many more. In doing so, the researcher has brought the concept of Krishan Kumar and M. Keith Booker. The theoretical concept of ‘anti-utopia’ is proposed by Krishan Kumar’s Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times. Simultaneously, concept of ‘cacotopia’ is proposed by M. Keith Booker in The Dystopian Impulse in Modern Literature which does not celebrate the end of the world rather it warns the mankind for their massive destructive activities which create artificial apocalypse. These philosophical concepts can be applied and vividly found in Martin Amis’s Einstein’s Monsters. Basically, this research paper focuses on the five stories namely “Bujak and the Strong Force,” “Insight at Flame Lake,” “The Time Disease,” “The Little Puppy That Could” and “The Immortals” where these stories portray the post nuclear apocalyptic vision which, obviously, demonstrates the philosophical concept of dystopia. It further explores the Bernard Brodie’s concept of nuclear deterrence which discourages in the launching of nuclear wars. The research paper also illustrates the ruin of European world of utopia by showing the destruction created by nuclear nukes. -

DOI: 10.1515/Genst-2017-0012 CLASS and GENDER

DOI: 10.1515/genst-2017-0012 CLASS AND GENDER – THE REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN IN KINGSLEY AMIS’S LUCKY JIM MILICA RAĐENOVIĆ “Dr Lazar Vrkatić” Faculty of Law and Business Studies 76, Oslobodenjia Blvd 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia [email protected] Abstract: Lucky Jim is one of the novels that mark the beginning of a small subgenre of contemporary fiction called the campus novel. It was written and published in the 1950s, a period when more women and working-class people started attending universities. This paper analyses the representation of women in terms of their gender and class. Keywords: campus novel, class, gender. 1. Introduction After six years of war, Great Britain was hungry for change and craved a more egalitarian society. After the Labour Party came to power in July 1945 with a huge parliamentary majority, the new government started paving the way for a Welfare State, which involved the expansion of the system of social security, providing pensions, sickness and unemployment benefits, a free National Health Service, the funding and expansion of the 183 secondary school system, and giving poor children greater opportunity to attend universities. The Conservative Party returned to power in 1951 but did not make any changes to the measures that brought about the creation of the Welfare State (Davies 2000:51). Once a great world power turned to reshaping its society, in which the class system would become a thing of the past, its people believed that they were living in a country that was going through great changes (Brannigan 2002:3). The Education Act of 1944 was intended to open universities to everyone and thus expand the trend of educational opportunities to the less privileged in the society. -

Caught Between Continents the Holocaust and Israel’S Attempt to Claim the European Jewish Diaspora

Caught between Continents The Holocaust and Israel’s Attempt to Claim the European Jewish Diaspora Zachary Kimmel Columbia University Abstract Israel’s idea of its sovereignty over Jewish cultural production has been essential in defining national mythology and self-consciousness ever since its founding as a state in 1948. But by what right does Israel make such claims? This article examines that question through exploring three legal cases: Franz Kafka’s manuscripts, the historical records of Jewish Vienna, and the literary estate of Lithuanian-born Chaim Grade. All three cases reveal a common jurisprudential and cultural logic, a rescue narrative that is central to the State of Israel itself. To this day, Israel maintains an idea of its sovereignty over Jewish cultural production, and a study of these cases demonstrates how the Holocaust plays as decisive a role in the creation and implementation of Israeli policy and jurisprudential practice as it has in its national identity more broadly. Article After decades of legal wrangling, a Tel Aviv court ruled in June 2015 that the manuscripts of Franz Kafka must be handed over to the National Library of Israel.1 The final batch of Kafka’s papers arrived in Jerusalem on August 7, 2019.2 Despite the fact that Kafka died in Prague in 1924, Israel’s lawyers argued that his manuscripts ought to be the legal property of the Jewish nation-state. Yet by what right does Israel make such claims—even over the claims of other nations where the artists in question were citizens, or ignoring the ethno- religious identifications of the artists themselves? This article examines that question, exploring the fate of Kafka’s manuscripts as well as legal battles over two other important archives with Jewish lineage: the historical records of Jewish Vienna and the literary estate of Lithuanian-born Chaim Grade. -

Narrative Topography: Fictions of Country, City, and Suburb in the Work of Virginia Woolf, W. G. Sebald, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Ian Mcewan

Narrative Topography: Fictions of Country, City, and Suburb in the Work of Virginia Woolf, W. G. Sebald, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Ian McEwan Elizabeth Andrews McArthur Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Elizabeth Andrews McArthur All rights reserved ABSTRACT Narrative Topography: Fictions of Country, City, and Suburb in the Work of Virginia Woolf, W. G. Sebald, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Ian McEwan Elizabeth Andrews McArthur This dissertation analyzes how twentieth- and early twenty-first- century novelists respond to the English landscape through their presentation of narrative and their experiments with novelistic form. Opening with a discussion of the English planning movement, “Narrative Topography” reveals how shifting perceptions of the structure of English space affect the content and form of the contemporary novel. The first chapter investigates literary responses to the English landscape between the World Wars, a period characterized by rapid suburban growth. It reveals how Virginia Woolf, in Mrs. Dalloway and Between the Acts, reconsiders which narrative choices might be appropriate for mobilizing and critiquing arguments about the relationship between city, country, and suburb. The following chapters focus on responses to the English landscape during the present era. The second chapter argues that W. G. Sebald, in The Rings of Saturn, constructs rural Norfolk and Suffolk as containing landscapes of horror—spaces riddled with sinkholes that lead his narrator to think about near and distant acts of violence. As Sebald intimates that this forms a porous “landscape” in its own right, he draws attention to the fallibility of representation and the erosion of cultural memory. -

Il Suo Legame Con Lo Scrittore Kingsley Amis Ha Fatto Storia Nella Swinging

FAMEstoria di donna DAMORE Il suo legame’ con lo scrittore Kingsley Amis ha fatto storia nella Swinging London. Elizabeth Jane Howard - una vita da seduttrice sfortunata - aveva la scrittura nel sangue. Il suo talento è esploso in tarda età, lontano dagli uomini... di STEFANIA BONACINA ALTA, LONGILINEA E CON UNA CASCATA di capelli biondi. La prima impres- sione che registrano gli occhi adolescenti di Martin Amis posandosi su Elizabeth Jane Howard, l’amante del padre, è quella di una dea in sottoveste che si reca in cucina per preparare a lui e ai suoi fratelli uova e pancetta. La scena si svolge nel 1962 nell’appartamento di Kingsley Amis, mattatore della scena letteraria. I due amanti si sono incontrati poche settimane prima al Festival letterario di Cheltenham, di cui lei era diret- trice artistica e lui oratore sul tema “sesso e censura”; un’attrazione così fatale da porre fine in pochi mesi ai rispettivi matrimoni. Questo incontro segnerà per l’au- trice best seller de La Saga dei Cazalet l’inizio di una nuova vita alla soglia dei 40 anni – «Ho riso con un uomo per la prima volta», dichiarerà in un’intervista – ma non sarà questa la fine della sua travagliata vita sentimentale. L’AMORE “MALATO” DEL PADRE Nata a Londra nel 1923 in una famiglia tanto al- to borghese quanto disfunzionale, Elizabeth sconterà tutta la vita una fame d’amore condita dalla mancanza di autostima accumulata durante l’infanzia. Il padre, David, svogliato erede di un impero di commercio di legnami ed eroe di guerra, la ama un po’ troppo al punto da “stringerle i seni e baciarla” durante l’adolescenza. -

Call No. Responsibility Item Publication Details Date Note 1

Call no. Responsibility Item Publication details Date Note TKNC0001 Roberts, H. Song, to a gay measure Dublin: printed at the Dolmen 1951 "200 copies." Neville Press TKNC0002 Promotional notice for Travelling tinkers, a book of Dolmen Press ballads by Sigerson Clifford TKNC0003 Promotional notice for Freebooters by Mauruce Kennedy Dolmen Press TKNC0004 Advertisement for Dolmen Press Greeting cards &c Dolmen Press TKNC0005 The reporter: the magazine of facts and ideas. Volume July 16, 1964 contains 'In the 31 no. 2 beginning' (verse) by Thomas Kinsella TKNC0006 Clifford, Travelling tinkers Dublin: Dolmen Press 1951 Of one hundred special Sigerson copies signed by the author this is number 85. Insert note from Thomas Kinsella. TKNC0007 Kinsella, Thomas The starlit eye / Thomas Kinsella ; drawings by Liam Dublin: Dolmen Press 1952 Set and printed by hand Miller at the Dolmen Press, Dublin, in an edition of 175 copies. March 1952. (p. [8]). TKNC0008 Kinsella, Thomas Galley proof of Poems [Glenageary, County Dublin]: 1956 Galley proof Dolmen Press TKNC0009 Kinsella, Thomas The starlit eye / Thomas Kinsella ; drawings by Liam Dublin : Dolmen Press 1952 Of twenty five special Miller copies signed by the author this is number 20. Set and printed by hand at the Dolmen Press, Dublin, in an edition of 175 copies. March 1952. TKNC0010 Promotional postcard for Love Duet from the play God's Dolmen Press gentry by Donagh MacDonagh TKNC0011 Irish writing. No. 24 Special issue - Young writers issue Dublin Sep-53 1 Thomas Kinsella Collection Listing Call no. Responsibility Item Publication details Date Note TKNC0012 Promotional notice for Dolmen Chapbook 3, The perfect Dolmen Press 1955 wife a fable by Robert Gibbings with wood engravings by the author TKNC0013 Pat and Mick Broadside no. -

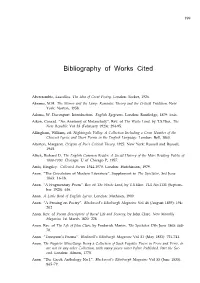

Bibliography of Works Cited

199 Bibliography of Works Cited Abercrombie, Lascelles. The Idea of Great Poetry. London: Secker, 1926. Abrams, M.H. The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition. New York: Norton, 1958. Adams, W. Davenport. Introduction. English Epigrams. London: Routledge, 1879: i-xix. Aiken, Conrad. “An Anatomy of Melancholy”. Rev. of The Waste Land, by T.S.Eliot. The New Republic Vol 33 (February 1923): 294-95. Allingham, William, ed. Nightingale Valley: A Collection Including a Great Number of the Choicest Lyrics and Short Poems in the English Language. London: Bell, 1860. Alterton, Margaret. Origins of Poe’s Critical Theory. 1925. New York: Russell and Russell, 1965. Altick, Richard D. The English Common Reader. A Social History of the Mass Reading Public of 1800-1900. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1957. Amis, Kingsley. Collected Poems 1944-1979. London: Hutchinson, 1979. Anon. “The Circulation of Modern Literature”. Supplement to The Spectator, 3rd June 1863: 16-18. Anon. “A Fragmentary Poem”. Rev of The Waste Land, by T.S.Eliot. TLS No.1131 (Septem- ber 1923): 616. Anon. A Little Book of English Lyrics. London: Methuen, 1900. Anon. “A Prosing on Poetry”. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine Vol 46 (August 1839): 194- 202. Anon. Rev. of Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery, by John Clare. New Monthly Magazine 1st March 1820: 228 Anon. Rev. of The Life of John Clare, by Frederick Martin. The Spectator 17th June 1865: 668- 70. Anon. “Tennyson’s Poems”. Blackwell’s Edinburgh Magazine Vol 31 (May 1832): 721-741. Anon. The Fugitive Miscellany: Being a Collection of Such Fugitive Pieces in Prose and Verse, as are not in any other Collection, with many pieces never before Published. -

HUK+Adult+FW1920+Catalogue+-+

Saving You By (author) Charlotte Nash Sep 17, 2019 | Paperback $24.99 | Three escaped pensioners. One single mother. A road trip to rescue her son. The new emotionally compelling page-turner by Australia's Charlotte Nash In their tiny pale green cottage under the trees, Mallory Cook and her five-year- old son, Harry, are a little family unit who weather the storms of life together. Money is tight after Harry's father, Duncan, abandoned them to expand his business in New York. So when Duncan fails to return Harry after a visit, Mallory boards a plane to bring her son home any way she can. During the journey, a chance encounter with three retirees on the run from their care home leads Mallory on an unlikely group road trip across the United States. 9780733636479 Zadie, Ernie and Jock each have their own reasons for making the journey and English along the way the four of them will learn the lengths they will travel to save each other - and themselves. 384 pages Saving You is the beautiful, emotionally compelling page-turner by Charlotte Nash, bestselling Australian author of The Horseman and The Paris Wedding. Subject If you love the stories of Jojo Moyes and Fiona McCallum you will devour this FICTION / Family Life / General book. 'I was enthralled... Nash's skilled storytelling will keep you turning pages until Distributor the very end.' FLEUR McDONALD Hachette Book Group Contributor Bio Charlotte Nash is the bestselling author of six novels, including four set in country Australia, and The Paris Wedding, which has been sold in eight countries and translated into multiple languages.