The Adrenergic Stress Response in Fish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronic Stress Makes People Sick. but How? and How Might We Prevent Those Ill Effects?

Sussing Out TRESS SChronic stress makes people sick. But how? And how might we prevent those ill effects? By Hermann Englert oad rage, heart attacks, migraine headaches, stom- ach ulcers, irritable bowel syndrome, hair loss among women—stress is blamed for all those and many other ills. Nature provided our prehistoric ancestors with a tool to help them meet threats: a Rquick activation system that focused attention, quickened the heartbeat, dilated blood vessels and prepared muscles to fight or flee the bear stalking into their cave. But we, as modern people, are sub- jected to stress constantly from commuter traffic, deadlines, bills, angry bosses, irritable spouses, noise, as well as social pressure, physical sickness and mental challenges. Many organs in our bodies are consequently hit with a relentless barrage of alarm signals that can damage them and ruin our health. 56 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN MIND COPYRIGHT 2003 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC. Daily pressures raise our stress level, but our ancient stress reactions—fight or flight—do not help us survive this kind of tension. www.sciam.com 57 COPYRIGHT 2003 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC. What exactly happens in our brains and bod- mone (CRH), a messenger compound that un- ies when we are under stress? Which organs are leashes the stress reaction. activated? When do the alarms begin to cause crit- CRH was discovered in 1981 by Wylie Vale ical problems? We are only now formulating a co- and his colleagues at the Salk Institute for Biolog- herent model of how ongoing stress hurts us, yet ical Studies in San Diego and since then has been in it we are finding possible clues to counteract- widely investigated. -

Love, Marriage, and Divorce: Newlyweds' Stress Hormones

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology Copyright 2003 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2003, Vol. 71, No. 1, 176–188 0022-006X/03/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.176 Love, Marriage, and Divorce: Newlyweds’ Stress Hormones Foreshadow Relationship Changes Janice K. Kiecolt-Glaser Cynthia Bane Ohio State University College of Medicine and Ohio State Ohio State University Institute for Behavioral Medicine Research Ronald Glaser and William B. Malarkey Ohio State University College of Medicine and Ohio State Institute for Behavioral Medicine Research Neuroendocrine function, assessed in 90 couples during their first year of marriage (Time 1), was related to marital dissolution and satisfaction 10 years later. Compared to those who remained married, epinephrine levels of divorced couples were 34% higher during a Time 1 conflict discussion, 22% higher throughout the day, and both epinephrine and norepinephrine were 16% higher at night. Among couples who were still married, Time 1 conflict ACTH levels were twice as high among women whose marriages were troubled 10 years later than among women whose marriages were untroubled. Couples whose marriages were troubled at follow-up produced 34% more norepinephrine during conflict, 24% more norepinephrine during the daytime, and 17% more during nighttime hours at Time 1 than the untroubled. Broadly stated, social learning models suggest that disordered Bradbury’s (1999b) “two factor” hypothesis suggests that aggres- communication promotes poor marital outcomes (Bradbury & sion and aggressive tendencies appear to be a key risk factor for Carney, 1993). Although communication measures have been early divorces, whereas marital communication contributes to the linked to marital discord and divorce across a number of studies, variability in satisfaction in intact marriages. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Clarke et al. 10.1073/pnas.1607237113 Major Axes of Shape Variation and Their Anatomical a comparison: the crown teleost vs. stem teleost comparison on Correlates molecular timescales. Here, the larger SL dataset delivers a All relative warp axes that individually account for >5% of the majority of trees where crown teleosts possess significantly variation across the species sampled are displayed in Table S3. higher rates than stem teleosts, whereas the CS and pruned SL Morphospaces derived from the first three axes, containing all datasets find this result in a large minority (Fig. S3). 398 Mesozoic neopterygian species in our shape dataset, are Overall, these results suggest that choice of size metric is presented in Fig. S1. Images of sampled fossil specimens are also relatively unimportant for our dataset, and that the overall size included in Fig. S1 to illustrate the anatomical correlates of and taxonomic samplings of the dataset are more likely to in- shape axes. The positions of major neopterygian clades in mor- fluence subsequent results, despite those factors having a rela- phospace are indicated by different colors in Fig. S2. Major tively small influence here. Nevertheless, choice of metric may be teleost clades are presented in Fig. S2A and major holostean important for other datasets (e.g., different groups of organisms clades in Fig. S2B. or datasets of other biological/nonbiological structures), because RW1 captures 42.53% of the variance, reflecting changes from it is possible to envisage scenarios where the choice of size metric slender-bodied taxa to deep-bodied taxa (Fig. S1 and Table S3). -

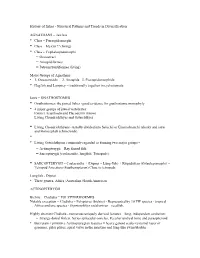

History of Fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification

History of fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification AGNATHANS = Jawless • Class – Pteraspidomorphi • Class – Myxini?? (living) • Class – Cephalaspidomorphi – Osteostraci – Anaspidiformes – Petromyzontiformes (living) Major Groups of Agnathans • 1. Osteostracida 2. Anaspida 3. Pteraspidomorphida • Hagfish and Lamprey = traditionally together in cyclostomata Jaws = GNATHOSTOMES • Gnathostomes: the jawed fishes -good evidence for gnathostome monophyly. • 4 major groups of jawed vertebrates: Extinct Acanthodii and Placodermi (know) Living Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes • Living Chondrichthyans - usually divided into Selachii or Elasmobranchi (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (chimeroids). • • Living Osteichthyans commonly regarded as forming two major groups ‑ – Actinopterygii – Ray finned fish – Sarcopterygii (coelacanths, lungfish, Tetrapods). • SARCOPTERYGII = Coelacanths + (Dipnoi = Lung-fish) + Rhipidistian (Osteolepimorphi) = Tetrapod Ancestors (Eusthenopteron) Close to tetrapods Lungfish - Dipnoi • Three genera, Africa+Australian+South American ACTINOPTERYGII Bichirs – Cladistia = POLYPTERIFORMES Notable exception = Cladistia – Polypterus (bichirs) - Represented by 10 FW species - tropical Africa and one species - Erpetoichthys calabaricus – reedfish. Highly aberrant Cladistia - numerous uniquely derived features – long, independent evolution: – Strange dorsal finlets, Series spiracular ossicles, Peculiar urohyal bone and parasphenoid • But retain # primitive Actinopterygian features = heavy ganoid scales (external -

Fine Structure of the Gas Bladder of Alligator Gar, Atractosteus Spatula Ahmad Omar-Ali1, Wes Baumgartner2, Peter J

www.symbiosisonline.org Symbiosis www.symbiosisonlinepublishing.com International Journal of Scientific Research in Environmental Science and Toxicology Research Article Open Access Fine Structure of the Gas Bladder of Alligator Gar, Atractosteus spatula Ahmad Omar-Ali1, Wes Baumgartner2, Peter J. Allen3, Lora Petrie-Hanson1* 1Department of Basic Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA 2Department of Pathobiology and Population Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA 3Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Aquaculture, College of Forest Resources, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA Received: 1 November, 2016; Accepted: 2 December, 2016 ; Published: 12 December, 2016 *Corresponding author: Lora Petrie-Hanson, Associate Professor, College of Veterinary Medicine, 240 Wise Center Drive PO Box 6100, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA, Tel: +1-(601)-325-1291; Fax: +1-(662)325-1031; E-mail: [email protected] Lepisosteidae includes the genera Atractosteus and Lepisosteus. Abstract Atractosteus includes A. spatula (alligator gar), A. tristoechus Anthropogenic factors seriously affect water quality and (Cuban gar), and A. tropicus (tropical gar), while Lepisosteus includes L. oculatus (spotted gar), L. osseus (long nose gar), L. in the Mississippi River and the coastal estuaries. Alligator gar platostomus (short nose gar), and L. platyrhincus (Florida gar) (adversely affect fish )populations. inhabits these Agricultural waters andrun-off is impactedaccumulates by Atractosteus spatula [2,6,7]. Atractosteus are distinguishable from Lepisosteus by agricultural pollution, petrochemical contaminants and oil spills. shorter, more numerous gill rakers and a more prominent accessory organ. The gas bladder, or Air Breathing Organ (ABO) of second row of teeth in the upper jaw [2]. -

Body-Shape Diversity in Triassic–Early Cretaceous Neopterygian fishes: Sustained Holostean Disparity and Predominantly Gradual Increases in Teleost Phenotypic Variety

Body-shape diversity in Triassic–Early Cretaceous neopterygian fishes: sustained holostean disparity and predominantly gradual increases in teleost phenotypic variety John T. Clarke and Matt Friedman Comprising Holostei and Teleostei, the ~32,000 species of neopterygian fishes are anatomically disparate and represent the dominant group of aquatic vertebrates today. However, the pattern by which teleosts rose to represent almost all of this diversity, while their holostean sister-group dwindled to eight extant species and two broad morphologies, is poorly constrained. A geometric morphometric approach was taken to generate a morphospace from more than 400 fossil taxa, representing almost all articulated neopterygian taxa known from the first 150 million years— roughly 60%—of their history (Triassic‒Early Cretaceous). Patterns of morphospace occupancy and disparity are examined to: (1) assess evidence for a phenotypically “dominant” holostean phase; (2) evaluate whether expansions in teleost phenotypic variety are predominantly abrupt or gradual, including assessment of whether early apomorphy-defined teleosts are as morphologically conservative as typically assumed; and (3) compare diversification in crown and stem teleosts. The systematic affinities of dapediiforms and pycnodontiforms, two extinct neopterygian clades of uncertain phylogenetic placement, significantly impact patterns of morphological diversification. For instance, alternative placements dictate whether or not holosteans possessed statistically higher disparity than teleosts in the Late Triassic and Jurassic. Despite this ambiguity, all scenarios agree that holosteans do not exhibit a decline in disparity during the Early Triassic‒Early Cretaceous interval, but instead maintain their Toarcian‒Callovian variety until the end of the Early Cretaceous without substantial further expansions. After a conservative Induan‒Carnian phase, teleosts colonize (and persistently occupy) novel regions of morphospace in a predominantly gradual manner until the Hauterivian, after which expansions are rare. -

Morphological Phylogeny of Sturgeons

Morphological Phylogeny of Sturgeons Biological Classification of Sturgeons and Paddlefishes Kingdom Anamalia Multicellular organism Phylum Chordata Vertebrates Superclass Osteichthyes Bony Fishes Class Actinopterygii Ray-finned fishes Subclass Chondrostei Cartilaginous and ossified bony fish Order Acipenseriformes Sturgeons and Paddlefishes Family Acipenseridae Sturgeons Genus Species Acipenser Huso Pseudoscaphirhynchus Scaphirhynchus Family Polydontidae Paddlefishes Genus Species Polydon Psephurus Currently there are 31 species within the order “Acipenseriformes” which contains two paddlefish species and 29 sturgeon species. Sturgeons and paddlefishes are a unique order of fishes due to their interesting physical and internal morphological characteristics. Polydontidae Acipenseridae Acipenser Huso Scaphirhynchus Pseudoscaphirhynchus Sturgeons and Paddlefishes Acipenseriformes Teleostei Holostei Chondrostei Polypteriformes Birchirs and Reedfishes Ray-Finned Bony Fishes • •Dorsal Finlets Jawed Fishes •Ganoid Scales •Cartilaginous Skeleton Actinopterygii •Rudimentary Lungs •Paired Fins •Heterocercal Tail Osteichthyes Sarcopterygii Sharks, Skates, Rays (Bony Fishes) Lobe-Finned Bony Fishes Chondrichthyes Coelacanth, Lungfishes, tetrapods •Fleshy, Lobed, Paired Fins •Complex Limbs •Enamel Covered Teeth Agnatha •Symmetrical Tail Lamprey, Hagfish •Jawless Fishes •Distinct Notocord •Paired Fins Absent Acipenseriformes likely evolved between the late Jurassic and early Cretaceous geological periods (70 to 170 million years ago). The word “sturgeon” -

Poverty Raises Levels of the Stress Hormone Cortisol: Evidence from Weather Shocks in Kenya*

Poverty Raises Levels of the Stress Hormone Cortisol: Evidence from Weather Shocks in Kenya* Johannes Haushofer, Joost de Laat, Matthieu Chemin October 21, 2012 Abstract Does poverty lead to stress? Despite numerous studies showing correlations between socioeconomic status and levels of the stress hormone cortisol, it remains unknown whether this relationship is causal. We used random weather shocks in Kenya to address this question. Our identication strategy exploits the fact that rainfall is an important input for farmers, but not for non-farmers such as urban artisans. We obtained salivary cortisol samples from poor rural farmers in Kianyaga district, Kenya, and informal metal workers in Nairobi, Kenya, together with GPS coordinates for household location and high-resolution infrared satellite imagery meausring rainfall. Since rainfall is a main input into agricultural production in the region, the absence of rain constitutes a random negative income shock for farmers, but not for non-farmers. We nd that low levels of rain increase cortisol levels with a temporal lag of 10-20 days; crucially, this eect is larger in farmers than in non-farmers. Both rain and cortisol levels are correlated with self-reported worries about life. Together, these ndings suggest that negative events lead to increases in worries and the stress hormone cortisol in poor people. JEL Codes: C93, D03, D87, O12 Keywords: weather shocks, rainfall, cortisol, stress, worries *We thank Ernst Fehr, David Laibson, Esther Duo, Abhijit Banerjee, and the members of the Harvard Program in History, Politics, and Economics for valuable feedback; Ellen Moscoe, Averie Baird, and Robin Audy for excellent research assistance; and Tavneet Suri for providing the rainfall data. -

Stress Adaptation and the Brainstem with Focus on Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Stress Adaptation and the Brainstem with Focus on Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Tiago Chaves 1,2, Csilla Lea Fazekas 1,2, Krisztina Horváth 1,2, Pedro Correia 1,2, Adrienn Szabó 1,2, Bibiána Török 1,2, Krisztina Bánrévi 1 and Dóra Zelena 1,3,* 1 Laboratory of Behavioural and Stress Studies, Institute of Experimental Medicine, 1083 Budapest, Hungary; [email protected] (T.C.); [email protected] (C.L.F.); [email protected] (K.H.); [email protected] (P.C.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (B.T.); [email protected] (K.B.) 2 Janos Szentagothai School of Neurosciences, Semmelweis University, 1083 Budapest, Hungary 3 Centre for Neuroscience, Szentágothai Research Centre, Institute of Physiology, Medical School, University of Pécs, 7624 Pécs, Hungary * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Stress adaptation is of utmost importance for the maintenance of homeostasis and, therefore, of life itself. The prevalence of stress-related disorders is increasing, emphasizing the importance of exploratory research on stress adaptation. Two major regulatory pathways exist: the hypothalamic– pituitary–adrenocortical axis and the sympathetic adrenomedullary axis. They act in unison, ensured by the enormous bidirectional connection between their centers, the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), and the brainstem monoaminergic cell groups, respectively. PVN and especially their corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) producing neurons are considered to be the centrum of stress regulation. However, the brainstem seems to be equally important. Therefore, Citation: Chaves, T.; Fazekas, C.L.; we aimed to summarize the present knowledge on the role of classical neurotransmitters of the Horváth, K.; Correia, P.; Szabó, A.; brainstem (GABA, glutamate as well as serotonin, noradrenaline, adrenaline, and dopamine) in stress Török, B.; Bánrévi, K.; Zelena, D. -

Subject Index Volume 23 Number S2

SUBJECT INDEX VOLUME 23 NUMBER S2 A B Cigarette smoking, S150 Circadian salivary cortisol levels, S105 Abnormal neuroendocrine, S97 B12 vitamin, S140 Circannual melatonin, S108 Abstinent male alcoholics, S156 Beclomethasone-induced vasoconstriction Circuitry pharmacotherapy, S73–S75 Academia, S10 (BIV), S121 Clinical diagnosis, S115 Academically-striving countries, S59 Bed nucleus of the stria terminals, S111 Clinical Global Impression Scale, S116 ACE gene, S130 Behavior problems, S100 Clinical trials, S43 ACE I/D polymorphism, S106 Behavioral effects of NK1, S23 Clobazam, S3 ACTH secretion, S29 Behavioral endocrine responses, S119 Clonidine administration, S132, S139 Acute adolescent mania, S124 Benign intracranial hypertension, S136 Clorniphene, S78 Acute major depressive disorder, S113 Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, Clozapine, S54, S116, S123, S135 Acute schizophrenia, S122 S124 Cocaine, S17, S46, S133 Addiction, S17, S102 Benzodiazapines, S56 Cognition, S51, S79, S92–S94 Administrative arrangements, S9 Benzothiophenes, S79 Cognitive aging, S94 Adolescent, S82 Bilateral grand mal seizure, S91 Cognitive dysfunction, S128 Adrenal hyperplasia, S60 Biochemical markers, S110 Cognitive functioning, S8 Adrenal insufficiency, S48 Biogenic amine systems, S43 Cognitive therapeutic considerations, S99 Adrenalectomy treatment, S145 Biological Psychiatry, S35 Collaboration, S58 -, ␣2-adrenergic receptors, S3 Biosynthesis, S70 Collegium International A2-adrenoceptor supersensibility, S139 Bipolar adolescents, S124 NeuroPsychopharmacologicum, -

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 19002010

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 Author(s): Noel M. Burkhead Reviewed work(s): Source: BioScience, Vol. 62, No. 9 (September 2012), pp. 798-808 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the American Institute of Biological Sciences Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/bio.2012.62.9.5 . Accessed: 21/09/2012 12:59 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and American Institute of Biological Sciences are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to BioScience. http://www.jstor.org Articles Articles Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 NOEL M. BURKHEAD Widespread evidence shows that the modern rates of extinction in many plants and animals exceed background rates in the fossil record. In the present article, I investigate this issue with regard to North American freshwater fishes. From 1898 to 2006, 57 taxa became extinct, and three distinct populations were extirpated from the continent. Since 1989, the numbers of extinct North American fishes have increased by 25%. From the end of the nineteenth century to the present, modern extinctions varied by decade but significantly increased after 1950 (post-1950s mean = 7.5 extinct taxa per decade). -

Teleost Fishes (The Teleostei)

OEB 130: BIOLOGY OF FISHES Lecture 4: Overview of ray-finned fish diversity (Actinopterygii) Announcements 1 1. Please review the syllabus for reading and lab information! 2. Please do the readings: for this week posted now. 3. Lab sections: 4. i) Dylan Wainwright, Thursday 2 - 4/5 pm ii) Kelsey Lucas, Friday 2 - 4/5 pm iii) Labs are in the Northwest Building basement (room B141) Please be on time at 2pm! 4. Lab sections done: first lab this week tomorrow! 5. First lab reading: Agassiz fish story; lab will be a bit shorter 6. Office hours to come Announcements 2 8 pages of general information on fish external anatomy and characters to help you learn some basic external fish anatomy and terminology – the last slides in the uploaded lecture Powerpoint file for today. Please look at these before lab this week, but no need to bring them in with you. Scanned from: Hastings, P. A., Walker, H. J. and Galland, G. R. (2014). Fishes: A guide to their diversity: Univ. of California Press. Next Monday: prepare to draw/diagram in lecture (colored pencils/pens will be useful) Lecture outline Lecture outline: 1. Brief review of the phylogeny and key traits so far 2. Actinopterygian clade: overview and introduction to key groups and selected key traits 3. Special focus on: 1. Fin ray structure and function 2. Lung and swimblader evolution 3. Early diversity of teleost fishes Selected key shared derived characters (synapomorphies) Review from last lecture Chondrichthyes (sharks and rays and ratfishes): 1. Dentition: multiple rows of unattached teeth 2.