Fish Diversity & Diseases Archaebacteria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O2 Secretion in the Eye and Swimbladder of Fishes

1641 The Journal of Experimental Biology 209, 1641-1652 Published by The Company of Biologists 2007 doi:10.1242/jeb.003319 Historical reconstructions of evolving physiological complexity: O2 secretion in the eye and swimbladder of fishes Michael Berenbrink School of Biological Sciences, The University of Liverpool, Biosciences Building, Crown Street, Liverpool, L69 7ZB, UK e-mail: [email protected] Accepted 12 March 2007 Summary The ability of some fishes to inflate their compressible value of haemoglobin. These changes predisposed teleost swimbladder with almost pure oxygen to maintain neutral fishes for the later evolution of swimbladder oxygen buoyancy, even against the high hydrostatic pressure secretion, which occurred at least four times independently several thousand metres below the water surface, has and can be associated with increased auditory sensitivity fascinated physiologists for more than 200·years. This and invasion of the deep sea in some groups. It is proposed review shows how evolutionary reconstruction of the that the increasing availability of molecular phylogenetic components of such a complex physiological system on a trees for evolutionary reconstructions may be as important phylogenetic tree can generate new and important insights for understanding physiological diversity in the post- into the origin of complex phenotypes that are difficult to genomic era as the increase of genomic sequence obtain with a purely mechanistic approach alone. Thus, it information in single model species. is shown that oxygen secretion first evolved in the eyes of fishes, presumably for improved oxygen supply to an Glossary available online at avascular, metabolically active retina. Evolution of this http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/210/9/1641/DC1 system was facilitated by prior changes in the pH dependence of oxygen-binding characteristics of Key words: oxygen secretion, Root effect, rete mirabile, choroid, haemoglobin (the Root effect) and in the specific buffer swimbladder, phylogenetic reconstruction. -

Respiratory Disorders of Fish

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Disorders of the Respiratory System in Pet and Ornamental Fish a, b Helen E. Roberts, DVM *, Stephen A. Smith, DVM, PhD KEYWORDS Pet fish Ornamental fish Branchitis Gill Wet mount cytology Hypoxia Respiratory disorders Pathology Living in an aquatic environment where oxygen is in less supply and harder to extract than in a terrestrial one, fish have developed a respiratory system that is much more efficient than terrestrial vertebrates. The gills of fish are a unique organ system and serve several functions including respiration, osmoregulation, excretion of nitroge- nous wastes, and acid-base regulation.1 The gills are the primary site of oxygen exchange in fish and are in intimate contact with the aquatic environment. In most cases, the separation between the water and the tissues of the fish is only a few cell layers thick. Gills are a common target for assault by infectious and noninfectious disease processes.2 Nonlethal diagnostic biopsy of the gills can identify pathologic changes, provide samples for bacterial culture/identification/sensitivity testing, aid in fungal element identification, provide samples for viral testing, and provide parasitic organisms for identification.3–6 This diagnostic test is so important that it should be included as part of every diagnostic workup performed on a fish. -

Ventilation Systems • Cilliary Action • Muscle Pumps – Buccal Pumps – Body Wall • Body Positioning • Ram Ventilation • Negative Pressure Diaphragms

3/27/2017 Ventilation • Increase exchange rate by moving medium over respiratory surface • Water – ~800x heavier than air, potentially expensive ventilation – Oxygen per unit mass • Air: 1.3 g contains 210 ml O2 • Water: 1000 g contains 5-10 ml O2 • Air – diffusion can only occur once gasses dissolved, all respiratory surfaces must be wet – Respiratory flux Systems • Ventilation system - devote resources to anatomical structures or behaviors aimed at increasing ventilation and thus potential gas exchange • Circulatory system – devote resources to anatomical structures to more efficiently move gasses (and other things) around the body – More efficient control and delivery 1 3/27/2017 Types of Ventilation Systems • Cilliary action • Muscle pumps – Buccal pumps – Body wall • Body positioning • Ram ventilation • Negative pressure diaphragms Air/Water Interaction with Surface 2 3/27/2017 Types of respiratory structures • Skin (cutaneous) • Gills – protruding structure, increases surface area – Tuft – Filament – Lamellar • Trachea – internalized but not centralized • Lung – internalized and centralized structure Cutaneous exchange • Most animals get some oxygen this way • Requires thin, moist skin • Flow of deoxygenated body fluids near skin surface • Ontogenetic trends – most larval fish do not use gills • Some secondary loss of lungs (Plethodontidae) • Ventilation (Lake Titicaca frog) 3 3/27/2017 Trachea systems • Multiple independent tubes • Spriacles for ventilation • Branches supply tissues directly • Some connected to “gills” • Body movement for ventilation Fish Gills • Ventilation – One way flow – pumps: buccal, opercular, stomach, esophageal – ram ventilation • Ventilation to profusion ratio = volume pumped to volume in contact with gills – Higher value requires more gill surface area 4 3/27/2017 • Types of gills – Holobranch: lamellae on both sides of the fillament – Hemibranch: lamellae on one side – Pseudobranch: no true lamellae Gills 5 3/27/2017 Gill area • Greater in marine than freshwater • Greater for more metabolically active fish (e.g. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Clarke et al. 10.1073/pnas.1607237113 Major Axes of Shape Variation and Their Anatomical a comparison: the crown teleost vs. stem teleost comparison on Correlates molecular timescales. Here, the larger SL dataset delivers a All relative warp axes that individually account for >5% of the majority of trees where crown teleosts possess significantly variation across the species sampled are displayed in Table S3. higher rates than stem teleosts, whereas the CS and pruned SL Morphospaces derived from the first three axes, containing all datasets find this result in a large minority (Fig. S3). 398 Mesozoic neopterygian species in our shape dataset, are Overall, these results suggest that choice of size metric is presented in Fig. S1. Images of sampled fossil specimens are also relatively unimportant for our dataset, and that the overall size included in Fig. S1 to illustrate the anatomical correlates of and taxonomic samplings of the dataset are more likely to in- shape axes. The positions of major neopterygian clades in mor- fluence subsequent results, despite those factors having a rela- phospace are indicated by different colors in Fig. S2. Major tively small influence here. Nevertheless, choice of metric may be teleost clades are presented in Fig. S2A and major holostean important for other datasets (e.g., different groups of organisms clades in Fig. S2B. or datasets of other biological/nonbiological structures), because RW1 captures 42.53% of the variance, reflecting changes from it is possible to envisage scenarios where the choice of size metric slender-bodied taxa to deep-bodied taxa (Fig. S1 and Table S3). -

History of Fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification

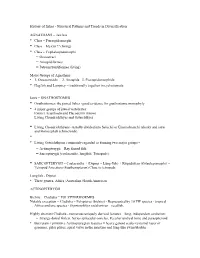

History of fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification AGNATHANS = Jawless • Class – Pteraspidomorphi • Class – Myxini?? (living) • Class – Cephalaspidomorphi – Osteostraci – Anaspidiformes – Petromyzontiformes (living) Major Groups of Agnathans • 1. Osteostracida 2. Anaspida 3. Pteraspidomorphida • Hagfish and Lamprey = traditionally together in cyclostomata Jaws = GNATHOSTOMES • Gnathostomes: the jawed fishes -good evidence for gnathostome monophyly. • 4 major groups of jawed vertebrates: Extinct Acanthodii and Placodermi (know) Living Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes • Living Chondrichthyans - usually divided into Selachii or Elasmobranchi (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (chimeroids). • • Living Osteichthyans commonly regarded as forming two major groups ‑ – Actinopterygii – Ray finned fish – Sarcopterygii (coelacanths, lungfish, Tetrapods). • SARCOPTERYGII = Coelacanths + (Dipnoi = Lung-fish) + Rhipidistian (Osteolepimorphi) = Tetrapod Ancestors (Eusthenopteron) Close to tetrapods Lungfish - Dipnoi • Three genera, Africa+Australian+South American ACTINOPTERYGII Bichirs – Cladistia = POLYPTERIFORMES Notable exception = Cladistia – Polypterus (bichirs) - Represented by 10 FW species - tropical Africa and one species - Erpetoichthys calabaricus – reedfish. Highly aberrant Cladistia - numerous uniquely derived features – long, independent evolution: – Strange dorsal finlets, Series spiracular ossicles, Peculiar urohyal bone and parasphenoid • But retain # primitive Actinopterygian features = heavy ganoid scales (external -

Fine Structure of the Gas Bladder of Alligator Gar, Atractosteus Spatula Ahmad Omar-Ali1, Wes Baumgartner2, Peter J

www.symbiosisonline.org Symbiosis www.symbiosisonlinepublishing.com International Journal of Scientific Research in Environmental Science and Toxicology Research Article Open Access Fine Structure of the Gas Bladder of Alligator Gar, Atractosteus spatula Ahmad Omar-Ali1, Wes Baumgartner2, Peter J. Allen3, Lora Petrie-Hanson1* 1Department of Basic Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA 2Department of Pathobiology and Population Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA 3Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Aquaculture, College of Forest Resources, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA Received: 1 November, 2016; Accepted: 2 December, 2016 ; Published: 12 December, 2016 *Corresponding author: Lora Petrie-Hanson, Associate Professor, College of Veterinary Medicine, 240 Wise Center Drive PO Box 6100, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA, Tel: +1-(601)-325-1291; Fax: +1-(662)325-1031; E-mail: [email protected] Lepisosteidae includes the genera Atractosteus and Lepisosteus. Abstract Atractosteus includes A. spatula (alligator gar), A. tristoechus Anthropogenic factors seriously affect water quality and (Cuban gar), and A. tropicus (tropical gar), while Lepisosteus includes L. oculatus (spotted gar), L. osseus (long nose gar), L. in the Mississippi River and the coastal estuaries. Alligator gar platostomus (short nose gar), and L. platyrhincus (Florida gar) (adversely affect fish )populations. inhabits these Agricultural waters andrun-off is impactedaccumulates by Atractosteus spatula [2,6,7]. Atractosteus are distinguishable from Lepisosteus by agricultural pollution, petrochemical contaminants and oil spills. shorter, more numerous gill rakers and a more prominent accessory organ. The gas bladder, or Air Breathing Organ (ABO) of second row of teeth in the upper jaw [2]. -

Body-Shape Diversity in Triassic–Early Cretaceous Neopterygian fishes: Sustained Holostean Disparity and Predominantly Gradual Increases in Teleost Phenotypic Variety

Body-shape diversity in Triassic–Early Cretaceous neopterygian fishes: sustained holostean disparity and predominantly gradual increases in teleost phenotypic variety John T. Clarke and Matt Friedman Comprising Holostei and Teleostei, the ~32,000 species of neopterygian fishes are anatomically disparate and represent the dominant group of aquatic vertebrates today. However, the pattern by which teleosts rose to represent almost all of this diversity, while their holostean sister-group dwindled to eight extant species and two broad morphologies, is poorly constrained. A geometric morphometric approach was taken to generate a morphospace from more than 400 fossil taxa, representing almost all articulated neopterygian taxa known from the first 150 million years— roughly 60%—of their history (Triassic‒Early Cretaceous). Patterns of morphospace occupancy and disparity are examined to: (1) assess evidence for a phenotypically “dominant” holostean phase; (2) evaluate whether expansions in teleost phenotypic variety are predominantly abrupt or gradual, including assessment of whether early apomorphy-defined teleosts are as morphologically conservative as typically assumed; and (3) compare diversification in crown and stem teleosts. The systematic affinities of dapediiforms and pycnodontiforms, two extinct neopterygian clades of uncertain phylogenetic placement, significantly impact patterns of morphological diversification. For instance, alternative placements dictate whether or not holosteans possessed statistically higher disparity than teleosts in the Late Triassic and Jurassic. Despite this ambiguity, all scenarios agree that holosteans do not exhibit a decline in disparity during the Early Triassic‒Early Cretaceous interval, but instead maintain their Toarcian‒Callovian variety until the end of the Early Cretaceous without substantial further expansions. After a conservative Induan‒Carnian phase, teleosts colonize (and persistently occupy) novel regions of morphospace in a predominantly gradual manner until the Hauterivian, after which expansions are rare. -

Morphological Phylogeny of Sturgeons

Morphological Phylogeny of Sturgeons Biological Classification of Sturgeons and Paddlefishes Kingdom Anamalia Multicellular organism Phylum Chordata Vertebrates Superclass Osteichthyes Bony Fishes Class Actinopterygii Ray-finned fishes Subclass Chondrostei Cartilaginous and ossified bony fish Order Acipenseriformes Sturgeons and Paddlefishes Family Acipenseridae Sturgeons Genus Species Acipenser Huso Pseudoscaphirhynchus Scaphirhynchus Family Polydontidae Paddlefishes Genus Species Polydon Psephurus Currently there are 31 species within the order “Acipenseriformes” which contains two paddlefish species and 29 sturgeon species. Sturgeons and paddlefishes are a unique order of fishes due to their interesting physical and internal morphological characteristics. Polydontidae Acipenseridae Acipenser Huso Scaphirhynchus Pseudoscaphirhynchus Sturgeons and Paddlefishes Acipenseriformes Teleostei Holostei Chondrostei Polypteriformes Birchirs and Reedfishes Ray-Finned Bony Fishes • •Dorsal Finlets Jawed Fishes •Ganoid Scales •Cartilaginous Skeleton Actinopterygii •Rudimentary Lungs •Paired Fins •Heterocercal Tail Osteichthyes Sarcopterygii Sharks, Skates, Rays (Bony Fishes) Lobe-Finned Bony Fishes Chondrichthyes Coelacanth, Lungfishes, tetrapods •Fleshy, Lobed, Paired Fins •Complex Limbs •Enamel Covered Teeth Agnatha •Symmetrical Tail Lamprey, Hagfish •Jawless Fishes •Distinct Notocord •Paired Fins Absent Acipenseriformes likely evolved between the late Jurassic and early Cretaceous geological periods (70 to 170 million years ago). The word “sturgeon” -

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 19002010

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 Author(s): Noel M. Burkhead Reviewed work(s): Source: BioScience, Vol. 62, No. 9 (September 2012), pp. 798-808 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the American Institute of Biological Sciences Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/bio.2012.62.9.5 . Accessed: 21/09/2012 12:59 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and American Institute of Biological Sciences are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to BioScience. http://www.jstor.org Articles Articles Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 NOEL M. BURKHEAD Widespread evidence shows that the modern rates of extinction in many plants and animals exceed background rates in the fossil record. In the present article, I investigate this issue with regard to North American freshwater fishes. From 1898 to 2006, 57 taxa became extinct, and three distinct populations were extirpated from the continent. Since 1989, the numbers of extinct North American fishes have increased by 25%. From the end of the nineteenth century to the present, modern extinctions varied by decade but significantly increased after 1950 (post-1950s mean = 7.5 extinct taxa per decade). -

Teleost Fishes (The Teleostei)

OEB 130: BIOLOGY OF FISHES Lecture 4: Overview of ray-finned fish diversity (Actinopterygii) Announcements 1 1. Please review the syllabus for reading and lab information! 2. Please do the readings: for this week posted now. 3. Lab sections: 4. i) Dylan Wainwright, Thursday 2 - 4/5 pm ii) Kelsey Lucas, Friday 2 - 4/5 pm iii) Labs are in the Northwest Building basement (room B141) Please be on time at 2pm! 4. Lab sections done: first lab this week tomorrow! 5. First lab reading: Agassiz fish story; lab will be a bit shorter 6. Office hours to come Announcements 2 8 pages of general information on fish external anatomy and characters to help you learn some basic external fish anatomy and terminology – the last slides in the uploaded lecture Powerpoint file for today. Please look at these before lab this week, but no need to bring them in with you. Scanned from: Hastings, P. A., Walker, H. J. and Galland, G. R. (2014). Fishes: A guide to their diversity: Univ. of California Press. Next Monday: prepare to draw/diagram in lecture (colored pencils/pens will be useful) Lecture outline Lecture outline: 1. Brief review of the phylogeny and key traits so far 2. Actinopterygian clade: overview and introduction to key groups and selected key traits 3. Special focus on: 1. Fin ray structure and function 2. Lung and swimblader evolution 3. Early diversity of teleost fishes Selected key shared derived characters (synapomorphies) Review from last lecture Chondrichthyes (sharks and rays and ratfishes): 1. Dentition: multiple rows of unattached teeth 2. -

Fish Diversity

Fish Diversity Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Universitas Indonesia Outline • Ancestry and relationships of major groups of fishes. • Living jawless fishes. • Chondrichtyes fishes. • Osteichthyes fishes. An Overview of Fish • Fish can be roughly defined (and there are a few exceptions) as cold- blooded creatures that have backbones, live in water, and have gills. • The gills enable fish to “breathe” underwater, without drawing oxygen from the atmosphere. • No other vertebrate but the fish is able to live without breathing air. One family of fish, the lungfish, is able to breathe air when mature and actually loses its functional gills. Another family of fish, the tuna, is considered warm-blooded by many people, but the tuna is an exception. Types of Scales Fins and Locomotion • Fish are propelled through the water by fins, body movement, or both. • A fish can swim even if its fins are removed, though it generally has difficulty with direction and balance. • Many kinds of fish jump regularly. Those that take to the air when hooked give anglers the greatest thrills. The jump is made to dislodge a hook or to escape a predator in close pursuit, or the fish may try to shake its body free of plaguing parasites. Types of Caudal Fins Fishes propel themselves through water in two very different ways, 1. The median and paired fins (MPF) 2. The body and/or caudal fins (BCF) Nutrition and The Digestive System • Many fish are strictly herbivores, eating only plant life. Many are purely plankton eaters. Most are carnivorous (in the sense of eating the flesh of other fish, as well as crustaceans, mollusks, and insects) or at least piscivorous (eating fish). -

1.0 Anatomy and Physiology of Salmonids

Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans AnimalUser Training Template 1.0 Anatomy and Physiology of Salmonids 1.1 Introduction: This template is intended for use by instructors to train the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) staff and students in the anatomy and physiology of salmonids. Templates are used to provide the minimum requirements necessary in a training exercise, but the instructor may add additional material. An experienced instructor must demonstrate the methods outlined in this template. Handson training of staff is a requirement for facility approval by the Canadian Council on Animal Care, of which DFO is a member. This template is part of a comprehensive DFO Science Branch series on training for users of aquatic research animals. 1.2 Rationale: There are over 50 species of fish and shellfish used as laboratory animals by the scientific community in Canada alone. Salmonid species are among the most common laboratory animals and include but are not limited to: Rainbow trout, Cutthroat trout, Atlantic salmon, Brook trout, Steelhead salmon, Brown trout, Arctic char, Lake trout, Chum salmon, Sockeye salmon, Pink salmon, Coho salmon and Chinook salmon. In order to properly identify abnormalities and signs of disease or distress in fish maintained for the purposes of scientific study, it is important to recognize and understand the basic anatomy and physiology of the species being studied. An understanding of anatomy is critical and ensures proper and humane methods are used for procedures such as blood sampling and tagging or marking with minimal longterm effect on the fish. 1.3 Authority: The staff, consultant veterinarian or Animal Care Committee is responsible for providing information about anatomy and physiology of the fish species used for scientific study in their respective regions.