Motion Event Framing in Fu'an Chinese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

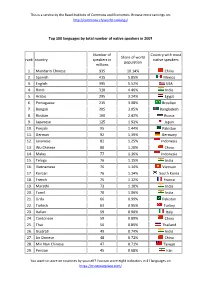

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE 2008 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE ★ 44–748 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas DONALD A. -

Language Surveys in Developing Nations

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 104 170 FL 006 842 AUTHOR Ohannessian, Sirirpi, Ed.; And Others TITLE Language Surveys in Developing Nations. Papersand Reports on Sociolinguistic Surveys. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 227p. AVAILABLE FROMCenter for Applied Linguistics,1611 North Kent Street, Arlington, Virginia 22209($8.50) EDRS PRICE Mr-$0.76 RC Not Available from EDRS..PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Developing Nations; Evaluation Methods; Language Patterns; Language Planning: *LanguageResearch; Language Role; *Language Usage;Nultilingualism; Official Languages; Public Policy;Sociocultural Patterns; *Sociolinguistics; *Surveys ABSTRACT This volume is a selection of papers preparedfor a conference on sociolinguistically orientedlanguage surveys organized by the Center for Applied Linguisticsand held in New York in September 1971. The purpose of theconference vas to review the role and function of such language surveysin the light of surveys conducted in recent years. The selectionis intended to give a general picture of such surveys to thelayman and to reflect the aims of the conference. The papers dealwith scope, problems, uses, organization, and techniques of surveys,and descriptions of particular surveys, and are mostly related tothe Eastern Africa Survey. The authors of theseselections are: Charles A. Ferguson, Ashok R. Kelkar, J. Donald Bowen, Edgar C.Polorm, Sitarpi Ohannessiam, Gilbert Ansre, Probodh B.Pandit, William D. Reyburn, Bonifacio P. Sibayan, Clifford H. Prator,Mervyn C. Alleyne, M. L. Bender, R. L. Cooper aLd Joshua A.Fishman. (Author/AN) Ohannessian, Ferquson, Polonic a a Center for Applied Linqirktie,, mit Language Surveys in Developing Nations papersand reportson sociolinguisticsurveys 2a Edited by Sirarpi Ohannessian, Charles A. Ferguson and Edgar C. Polomd Language Surveysin Developing Nations CY tie papers and reports on 49 LL sociolinguisticsurveys U S OE P MAL NT OF NEAL spt PERMISSION TO REPRODUCETMIT. -

Tonatory Patterns in Taizhou Wu Tones

TONATORY PATTERNS IN TAIZHOU WU TONES Phil Rose Emeritus Faculty, Australian National University [email protected] ABSTRACT 台州 subgroup of Wu to which Huángyán belongs. The issue has significance within descriptive Recordings of speakers of the Táizhou subgroup of tonetics, tonatory typology and historical linguistics. Wu Chinese are used to acoustically document an Wu dialects – at least the conservative varieties – interaction between tone and phonation first attested show a wide range of tonatory behaviour [11]. One in 1928. One or two of their typically seven or eight finds breathy or ventricular phonation in groups of tones are shown to have what sounds like a mid- tones characterising natural tonal classes of Rhyme glottal-stop, thus demonstrating a new importance for phonotactics and Wu’s complex tone pattern in Wu tonatory typology. Possibly reflecting sandhi. One also finds a single tone characterised by gradual loss, larygealisation appears restricted to the a different non-modal phonation type [12]; or even north and north-west, and is absent in Huángyán two different non-modal phonation types in two dialect where it was first described. A perturbatory tones. However, the Huangyan-type tonation seems model of the larygealisation is tested in an to involve a new variation, with the same phonation experiment determining how much of the complete type in two different tones from the same historical tonal F0 contour can be restored from a few tonal category, thus prompting speculation that it centiseconds of modal F0 at Rhyme onset and offset. developed before the tonal split. The results are used both to acoustically quantify laryngealised tonal F0, with its problematic jitter and 2. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

5066 Date: 2019-06-05

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 5066 Date: 2019-06-05 ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Coded Character Set Secretariat: Japan (JISC) Doc. Type: Disposition of comments Title: Draft disposition of comments on ISO/IEC CD.2 10646 6th edition Source: Michel Suignard (project editor) Project: JTC1.02.10646.00.00.00.06 Status: For review by WG2 Date: 2019-06-05 Distribution: WG2 Reference: SC2 N4654 N4660 N4661 WG2 N5013 N5021R N5058 N5065 Medium: Paper, PDF file Comments were received from China, France, Ireland, Japan, and USA. The following document is the draft disposition of those comments. An excerpt of the UK comments to ISO/IEC CD 10646 6th edition is also included as their disposition was modified after the original disposition was created. The disposition is organized per country. Note 1 – The Irish vote was tabulated as a positive vote with no comment in N4660. However, a late disapproval vote was received as N4661 and is treated as such in this disposition. Note 2 – With some minor exceptions, the full content of the ballot comments have been included in this document to facilitate the reading. The dispositions are inserted in between these comments and are marked in Underlined Bold Serif text, with explanatory text in italicized serif. Page 1 China: Positive with comments Technical comment T1. Mongolian China does not comment on Mongolian but may submit proposals on the whole block later. Proposed change by China None. Noted The same comment was made for the original CD ballot. Page 2 France: Positive with comments Technical comment T1. Page 268-269, 1D00-1D7F Phonetic Extensions – Latin superscript capital letters Latin superscript capital is not complete. -

Development of Basic Literacy Learning Materials for Minority Peoples in Asia and the Pacific

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 377 740 FL 800 845 TITLE Development of basic Literacy Learning Materials for Minority Peoples in Asia and the Pacific. Final Report of the Second Sub-Regional Workshop (Chiang Rai, Thailand, February 22-March 5, 1994). INSTITUTION Asian Cultural Centre for UNESCO, Tokyo (Japan).; Ministry of Education, Bangkok (Thailand).; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Bangkok (Thailand). Principal Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. PUB DATE Mar 94 NOTE 142p.; Illustrations contain small and broken print. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO6 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Classroom Techniques; *Educational Needs; Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; Instructional Effectiveness; *Instructional Materials; *Literacy Education; *Material Development; *Minority Groups; Teaching Methods; Uncommonly Taught Languages; Workshops IDENTIFIERS *Asia; Burma; China; Indonesia; Laos; Malaysia; Mongolia; Philippines; Thailand; Vietnam ABSTaACT A report of a regional workshop on development of instructional materials for basic literacy education of minority groups in Asia and the Pacific is presented.Countries represented include: China; Indonesia; Laos; Malaysia; Mongolia; Myanmar (Burma); Philippines; Vietnam; and Thailand. The workshop's objectives were to discuss the need for effective literacy learning materials, develop guidelines for preparing effective basic literacy learning materials for minority language populations, and suggest methods for their use. The report begins with an overview of the proceedings and resulting recommendations. Subsequent chapters summarize: needs and problems in education of minority populations; guidelines for preparation of effective basic literacy learning materials; studies of specific language groups; resource papers on Thai hill tribes and development of basic literacy materials in minority languages; a report from UNESCO and its Asian/Pacific Cultural Center; nine country reports; and national followup plans. -

Construction and Automatization of a Minnan Child Speech Corpus with Some Research Findings

Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Vol. 12, No. 4, December 2007, pp. 411-442 411 © The Association for Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Construction and Automatization of a Minnan Child Speech Corpus with some Research Findings Jane S. Tsay∗ Abstract Taiwanese Child Language Corpus (TAICORP) is a corpus based on spontaneous conversations between young children and their adult caretakers in Minnan (Taiwan Southern Min) speaking families in Chiayi County, Taiwan. This corpus is special in several ways: (1) It is a Minnan corpus; (2) It is a speech-based corpus; (3) It is a corpus of a language that does not yet have a conventionalized orthography; (4) It is a collection of longitudinal child language data; (5) It is one of the largest child corpora in the world with about two million syllables in 497,426 lines (utterances) based on about 330 hours of recordings. Regarding the format, TAICORP adopted the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES) [MacWhinney and Snow 1985; MacWhinney 1995] for transcribing and coding the recordings into machine-readable text. The goals of this paper are to introduce the construction of this speech-based corpus and at the same time to discuss some problems and challenges encountered. The development of an automatic word segmentation program with a spell-checker is also discussed. Finally, some findings in syllable distribution are reported. Keywords: Minnan, Taiwan Southern Min, Taiwanese, Speech Corpus, Child Language, CHILDES, Automatic Word Segmentation 1. Introduction Taiwanese Child Language Corpus is a corpus based on spontaneous conversations between young children and their adult caretakers in Minnan speaking families in Chiayi County, Taiwan. -

Meeting the Challenge: Preparing Chinese Language

Meeting the Challenge: Pre- paring Chinese Language Teachers for American Schools Meeting the Challenge: Preparing Chinese Language Teachers for American Schools Asia Society is the leading global and pan-Asian organization working to strengthen relationships and promote understanding among the peoples, leaders and institutions of Asia and the United States. We seek to increase knowledge and enhance dialogue, encour- age creative expression and generate new ideas across the !elds of policy, business, education, arts and culture. "e Asia Society Partnership for Global Learning develops youth to be globally competent citizens, workers, and leaders by equipping them with the knowledge and skills needed for success in an increasingly interconnected world. A critical part of this e#ort to build a world-class education system for all is to promote the learning of Chinese and world languages and cultures. For more information, or to browse our resources, please visit www.asiasociety.org/pgl ii ASIA SOCIETY Table of Contents Table of Contents Working Group 2 Preface & Acknowledgements 4 Introduction 6 I. A Changing World Requires Changing Skills 7 A.!e National Need for World Languages 8 B. !e Growth of Chinese Language Programs in the United States 10 II. Meeting the Future Demand for Chinese Language Teachers 17 A. Characteristics of an E"ective Chinese Language Teacher 18 B. Challenges Involved in Producing More Chinese Language Teachers 19 Recruiting 19 Tr a ining 22 Certi#cation and Licensure 27 Professional Development and Continuing Support -

Oujiang Wu Tones and Acoustic Reconstruction

OUJIANG WU TONES AND ACOUSTIC RECONSTRUCTION PHIL ROSE Linguistics (Arts), Australian National University 1. Introduction We do not expect tones, as phonological phenomena, to vary without limit, but to show similarities, or so-called tonological universals, across varieties (Maddieson 1978). Nevertheless, when one samples tones from different Asian tone languages, or even different dialects, they often show a great variety of pitch shapes. Zhu and Rose (1998) for example demonstrated no less than 25 different tones in four varieties from different sub-groups within the Wu dialects of east central China. (I use the term tone in this paper in a sense analogous to phone, that is, as a constellation of audibly different properties, with pitch predominating but also including length and phonation type, that constitutes observation data for phonological – usually tonemic – analysis.) In exploring the nature of phonological variation in Language, we naturally concentrate on differences. This paper, on the other hand, makes use of how similar tones can be. It looks at variation in tones at seven localities distributed over a fairly small geographical area where the varieties, which belong to the same dialectal sub-group, have been described as homogeneous. Although this study reveals some interesting synchronic linguistic-tonetic variation, the main reason for undertaking it is not typological, but, as befits a festschrift for Harold Koch, historical. As mentioned, the Wu dialects of Chinese are well-known for their tonal complexity. Not only do they exhibit probably the most complex tone sandhi in the world (Rose 1990), but they also show a bewildering variety in their citation tones. -

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance Zheyu Wei A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Creative Arts The University of Dublin, Trinity College 2017 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library Conditions of use and acknowledgement. ___________________ Zheyu Wei ii Summary This thesis is a study of Chinese experimental theatre from the year 1990 to the year 2014, to examine the involvement of Chinese theatre in the process of globalisation – the increasingly intensified relationship between places that are far away from one another but that are connected by the movement of flows on a global scale and the consciousness of the world as a whole. The central argument of this thesis is that Chinese post-Cold War experimental theatre has been greatly influenced by the trend of globalisation. This dissertation discusses the work of a number of representative figures in the “Little Theatre Movement” in mainland China since the 1980s, e.g. Lin Zhaohua, Meng Jinghui, Zhang Xian, etc., whose theatrical experiments have had a strong impact on the development of contemporary Chinese theatre, and inspired a younger generation of theatre practitioners. Through both close reading of literary and visual texts, and the inspection of secondary texts such as interviews and commentaries, an overview of performances mirroring the age-old Chinese culture’s struggle under the unprecedented modernising and globalising pressure in the post-Cold War period will be provided. -

South-East Asia Second Edition CHARLES S

Geological Evolution of South-East Asia Second Edition CHARLES S. HUTCHISON Geological Society of Malaysia 2007 Geological Evolution of South-east Asia Second edition CHARLES S. HUTCHISON Professor emeritus, Department of geology University of Malaya Geological Society of Malaysia 2007 Geological Society of Malaysia Department of Geology University of Malaya 50603 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Geological Society of Malaysia ©Charles S. Hutchison 1989 First published by Oxford University Press 1989 This edition published with the permission of Oxford University Press 1996 ISBN 978-983-99102-5-4 Printed in Malaysia by Art Printing Works Sdn. Bhd. This book is dedicated to the former professors at the University of Malaya. It is my privilege to have collabo rated with Professors C. S. Pichamuthu, T. H. F. Klompe, N. S. Haile, K. F. G. Hosking and P. H. Stauffer. Their teaching and publications laid the foundations for our present understanding of the geology of this complex region. I also salute D. ]. Gobbett for having the foresight to establish the Geological Society of Malaysia and Professor Robert Hall for his ongoing fascination with this region. Preface to this edition The original edition of this book was published by known throughout the region of South-east Asia. Oxford University Press in 1989 as number 13 of the Unfortunately the stock has become depleted in 2007. Oxford monographs on geology and geophysics.