The Nature of Public Participation in the Decision to Implement Shale Gas Mining: a Case Study of the Karoo Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Anthropological Study of Itinerancy and Domestic Fluidity Amongst the Karretjie People of the South African Karoo

CHILDHOOD: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY OF ITINERANCY AND DOMESTIC FLUIDITY AMONGST THE KARRETJIE PEOPLE OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN KAROO by SARAH ADRIANA STEYN submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject ANTHROPOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR M. DE JONGH MARCH 2009 Dedicated to my children, Luke and Sarah-Anne In memory of my siblings, Doria and Francois I declare that Childhood: An Anthropological Study of Itinerancy and Domestic Fluidity Amongst the Karretjie People of the South African Karoo is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. S A Steyn 2009.03.05 “The only difference between them and us is that we are ready to learn from them but they are not ready to learn from us ... in everyday life they must come to recognise us, respect us, value us ... for what we are. Only then will each one of us be able to discover the other”. (Words of a Roma delegate at a Conference organised by the Centre for Gypsy Research at the Université René Descartes, Paris, 1993) ABSTRACT The Karretjie People, or Cart People are a peripatetic community and are descendants of the KhoeKhoen and San, the earliest inhabitants of the Karoo region in South Africa. As a landless and disempowered community they are dependent upon others for food and other basic necessities specifically, and other resources generally. Compared to children in South Africa generally, the Karretjie children are in every sense of the most severely deprived. -

27 June 07 July

27 JUNE TO 07 JULY TWENTY NINETEEN Recommended Retail Price: R75 4 Festival Messages 6 Acknowledgements 9 Standard Bank Young Artist Award Winners 16 2018 Featured Artist 20 Curatorial Statement & Curatorial Team 22 Curated Programme 27 Main Programme 155 Fringe Programme 235 Travel and Accommodation 236 Booking Procedures 238 Index 241 Map We will be publishing an update to our Programme which will be available in Grahamstown throughout the Festival, at all of our Box Offices and Information Kiosks. This update will contain the latest possible information on performances and events, changes, cancellations and additional shows, a daily diary, map, local emergency services number, etc and is a must-have for all Festival-goers. Latest Programme changes and updates available at www.nationalartsfestival.co.za Images from left to right: Gas Lands (58), Moonless (31) and Wanderer (63) MAIN MAIN PROGRAMME FRINGE PROGRAMME Cover image: 27 155 Birthing Nureyev by Theatre Theatre leftfoot productions Director: Andre Odendaal Performer: Ignatius van Heerden 39 181 Designer: Gustav Steenkamp (Gustav-Henri Designstudio) Student Theatre Comedy Disclaimer: The Festival organisers have made 43 199 every effort to ensure that Comedy Illusion everything printed in this publication is accurate. However, mistakes and 46 203 changes do occur, and Public Art Family Theatre we do not accept any responsibility for them or for any inaccuracies 48 208 or misinformation within advertisements. Artists Family Theatre Dance provide images, logos and advertisements and we accept no responsibility for 57 214 the quality of reproduction Dance Music Theatre & Cabaret in this publication. 64 218 Visual & Performance Art Music Recital 82 220 Music Contemporary Music 105 224 Jazz Poetry 121 225 Film Festival Film 130 227 Critical Consciousness Visual Art 145 233 Creativate Spiritfest 4 Welcome to the Eastern Cape – the “Home of Legends”! 2019 sees the 45th edition of the National inspired. -

Nc Travelguide 2016 1 7.68 MB

Experience Northern CapeSouth Africa NORTHERN CAPE TOURISM AUTHORITY Tel: +27 (0) 53 832 2657 · Fax +27 (0) 53 831 2937 Email:[email protected] www.experiencenortherncape.com 2016 Edition www.experiencenortherncape.com 1 Experience the Northern Cape Majestically covering more Mining for holiday than 360 000 square kilometres accommodation from the world-renowned Kalahari Desert in the ideas? North to the arid plains of the Karoo in the South, the Northern Cape Province of South Africa offers Explore Kimberley’s visitors an unforgettable holiday experience. self-catering accommodation Characterised by its open spaces, friendly people, options at two of our rich history and unique cultural diversity, finest conservation reserves, Rooipoort and this land of the extreme promises an unparalleled Dronfield. tourism destination of extreme nature, real culture and extreme adventure. Call 053 839 4455 to book. The province is easily accessible and served by the Kimberley and Upington airports with daily flights from Johannesburg and Cape Town. ROOIPOORT DRONFIELD Charter options from Windhoek, Activities Activities Victoria Falls and an internal • Game viewing • Game viewing aerial network make the exploration • Bird watching • Bird watching • Bushmen petroglyphs • Vulture hide of all five regions possible. • National Heritage Site • Swimming pool • Self-drive is allowed Accommodation The province is divided into five Rooipoort has a variety of self- Accommodation regions and boasts a total catering accommodation to offer. • 6 fully-equipped • “The Shooting Box” self-catering chalets of six national parks, including sleeps 12 people sharing • Consists of 3 family units two Transfrontier parks crossing • Box Cottage and 3 open plan units sleeps 4 people sharing into world-famous safari • Luxury Tented Camp destinations such as Namibia accommodation andThis Botswanais the world of asOrange well River as Cellars. -

Health Risk Perception of Karoo Residents Related to Fracking, South Africa

Health risk perception of Karoo residents related to fracking, South Africa Mini-dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Public Health, 2015 Author: M. Willems Supervisor: Prof M.A. Dalvie Co-Supervisor: Prof L. London Co-Supervisor: Prof H.A. Rother The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Declaration Master in Public Health (General track) Mini-Dissertation I, Mieke Willems (WLLMIE001), declare that the work that I have submitted is my own and where the work of others has been used (whether quoted verbatim, paraphrased or referred to) it has been attributed and acknowledged. Signature: Date: 22April 2015 I PART 0: Preamble II Thesis Sections Overview Part 0: Preamble.............………………………………………………….……..……….………….…..II Part A: Protocol...........………………………………………….………………….………….…….……A-i Part B: Literature Review………………………………………………………..……………….……...B-i Part C: Manuscript Environmental Practice Journal…………………………………..……..C-i Part D: Appendices………………………………………………………………………….……………...D-1 III Dedication Page I would herewith like to dedicate this thesis to South Africa, our country whom I love far and wide. I wish that decisions will be made and based on long term vision and not economic gain. I hope that one day we will look back at the struggles we all faced and cherish the value of our efforts as we drink clean water, we roam the barely trodden beaches, the vast plains of grass, sand and rock and enjoy the infinity of our Karoo night sky. -

Water Resources

CHAPTER 5: WATER RESOURCES CHAPTER 5 Water Resources CHAPTER 5: WATER RESOURCES CHAPTER 5: WATER RESOURCES Integrating Authors P. Hobbs1 and E. Day2 Contributing Authors P. Rosewarne3 S. Esterhuyse4, R. Schulze5, J. Day6, J. Ewart-Smith2,M. Kemp4, N. Rivers-Moore7, H. Coetzee8, D. Hohne9, A. Maherry1 Corresponding Authors M. Mosetsho8 1 Natural Resources and the Environment (NRE), Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Pretoria, 0001 2 Freshwater Consulting Group, Cape Town, 7800 3 Independent Consultant, Cape Town 4 Centre for Environmental Management, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, 9300 5 Centre for Water Resources Research, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Scottsville, 3209 6 Institute for Water Studies, University of Western Cape, Bellville, 7535 7 Rivers-Moore Aquatics, Pietermaritzburg 8 Council for Geoscience, Pretoria, 0184 9 Department of Water and Sanitation, Northern Cape Regional Office, Upington, 8800 Recommended citation: Hobbs, P., Day, E., Rosewarne, P., Esterhuyse, S., Schulze, R., Day, J., Ewart-Smith, J., Kemp, M., Rivers-Moore, N., Coetzee, H., Hohne, D., Maherry, A. and Mosetsho, M. 2016. Water Resources. In Scholes, R., Lochner, P., Schreiner, G., Snyman-Van der Walt, L. and de Jager, M. (eds.). 2016. Shale Gas Development in the Central Karoo: A Scientific Assessment of the Opportunities and Risks. CSIR/IU/021MH/EXP/2016/003/A, ISBN 978-0-7988-5631-7, Pretoria: CSIR. Available at http://seasgd.csir.co.za/scientific-assessment-chapters/ Page 5-1 CHAPTER 5: WATER RESOURCES CONTENTS CHAPTER -

Murraysburg: Home of Ancient Mountain Dwellers

Rose Willis Murraysburg: Home of Ancient Mountain Dwellers Karoo Cameos Series Hosted by the Karoo Development Foundation MURRAYSBURG Home of ancient mountain dwellers By Rose Willis [email protected] 2021 Series editor: Prof Doreen Atkinson [email protected] ROSE WILLIS is the author of The Karoo Cookbook (2008), as well as the monthly e-journal Rose’s Round-up. She co-authored Yeomen of the Karoo: The Story of the Imperial Yeomanry Hospital at Deelfontein, with Arnold van Dyk and Kay de Villiers (2016). 1 Rose Willis is the author of The Karoo Cookbook (Ryno Struik Publishers, 2008), and the e-journal Rose’s Roundup. Rose Willis Murraysburg: Home of Ancient Mountain Dwellers A Karoo montane paradise Once an active, flourishing farming town, Murraysburg is today a typical, slumbering, old-world Karoo village. The town lies in a scenic area with many drives offering breath- taking scenery. Yet, the district has a very low rainfall – between 200mm and 500mm a year. Artesian springs of pure, sweet water bubble to the surface in several places even in the hottest conditions. Snowfalls are common in the mountains. Murraysburg is a Karoo montane paradise. 2 Rose Willis Murraysburg: Home of Ancient Mountain Dwellers Murraysburg ‘s “magical mountain” is Toorberg. With an elevation of 2 400m above sea level it is the third highest peak in the Western Cape and allows visitors to glimpse infinity. Streams, waterfalls and fountains, all fed by the winter snows, are found all over the mountain. From its peak visitors can enjoy exceptional views of the Camdeboo and eighteen surrounding districts. -

Fracking in the Karoo: a Case Study in Science Communication

Fracking in the Karoo: A case study in science communication by Janus Snyders Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts (Journalism) at Stellenbosch University Department of Journalism Faculty of Arts Supervisor: Prof. George Claassen March 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 1 September 2015 Signature: Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT The US Energy Information Administration estimates that South Africa could hold about 390 trillion cubic feet (tcf) (11 043 570 174 000 cubic meter) of shale gas in the Karoo basin. Only 5 tcf (141 584 233 000 cubic meter) thereof would be enough to meet the energy needs of 5 million households for 15 years. The South African government lifted the moratorium on shale gas exploration in September 2012 after the issuing of exploration licenses were suspended for 18 months. During this time a multidisciplinary team conducted research to gain more knowledge about the practice. After the big announcement, various media houses published the latest developments on their digital news platforms and allowed readers to comment on the issue of exploration and possible future shale gas mining activities (also known as fracturing or fracking) in the country. -

South Africa Yearbook 2013/2014 Tourism

SOUTH AFRICA YEARBOOK 2013/14 Tourism has taken its place as a vital contributor to economic growth, catapulting South Africa from a pariah prior to 1994 to one of the fastest-growing Tourism and most desired leisure holiday destinations in the world. The infl ow of tourists to South Africa is the result of the success of policies aimed at entrenching South Africa’s status as a major international tourism and business events destination. The purpose of the National Department of Tourism (NDT) is to be a catalyst for tourism growth and development in South Africa, and to drive the National Tourism Sector Strategy (NTSS). To ensure the achievement of the sector’s targets, the department supports the implemen- tation of the NTSS and work, towards increasing the number of foreign arrivals from 9 933 966 in 2009 to 12 068 030 by 2015, and increasing the number of domestic tourists from 14 600 000 in 2009 to 16 000 000 by 2015. In 2013/14, international tourist arrivals in South Africa grew by 10,2% year on year to almost 9,2 million. Europe remained the highest source of tourists, with arrivals growing by 9,5% year on year to 1 396 978 tourists. The United Kingdom (UK) was South Africa’s biggest overseas tourism market: 438 023 UK tourists travelled to South Africa. The United States of America (USA) was South Africa’s second biggest overseas market, with 326 643 tourists, followed by Germany with 266 333 tourists. France is now South Africa’s fi fth biggest overseas market with 122 244 tourists. -

Astro-Tourism, the Sublime, and the Karoo As a 'Space Destination'

Making the most of ‘nothing’: astro-tourism, the Sublime, and the Karoo as a ‘space destination’ Mark Ingle [email protected] Abstract In recent years perceptions of South Africa’s arid Karoo have been radically transformed. Whereas the Karoo was once regarded as a desolate wasteland, it is now being punted as a positively trendy region, both to live in and to explore. Many enterprising niche tourism operators have positioned themselves to profit from this phenomenon. This article briefly articulates the concept of ‘the Sublime’ and shows how the nexus of cognitive associations suggested by ‘space’ and ‘nothingness’ is being harnessed to rebrand the Karoo as a dynamic and desirable destination. The paper also reflects on how these developments might redound to the benefit of local communities and flags some of the tensions occasioned by the intrusion of tourism into a relatively undeveloped region. Introduction This article records how the quality of nothingness, which characterises South Africa’s arid Karoo in the public mind, has been transformed in recent times from a perceived liability into a touristic asset. It seeks to show how this metamorphosis is being facilitated by creative tourism entrepreneurship, and speculates on what the impact of niche tourism, and specifically ‘astro- tourism’, might be for the local inhabitants. The discussion commences with an analysis of how open spaces came to be venerated as integral to the nineteenth century Romantic movement, and introduces the concept of ‘the Sublime’ in nature. The early history of astronomy at the Cape is briefly summarised to contextualise current astronomical developments taking place in the Karoo. -

Dictionary of South African Place Names

DICTIONARY OF SOUTHERN AFRICAN PLACE NAMES P E Raper Head, Onomastic Research Centre, HSRC CONTENTS Preface Abbreviations ix Introduction 1. Standardization of place names 1.1 Background 1.2 International standardization 1.3 National standardization 1.3.1 The National Place Names Committee 1.3.2 Principles and guidelines 1.3.2.1 General suggestions 1.3.2.2 Spelling and form A Afrikaans place names B Dutch place names C English place names D Dual forms E Khoekhoen place names F Place names from African languages 2. Structure of place names 3. Meanings of place names 3.1 Conceptual, descriptive or lexical meaning 3.2 Grammatical meaning 3.3 Connotative or pragmatic meaning 4. Reference of place names 5. Syntax of place names Dictionary Place Names Bibliography PREFACE Onomastics, or the study of names, has of late been enjoying a greater measure of attention all over the world. Nearly fifty years ago the International Committee of Onomastic Sciences (ICOS) came into being. This body has held fifteen triennial international congresses to date, the most recent being in Leipzig in 1984. With its headquarters in Louvain, Belgium, it publishes a bibliographical and information periodical, Onoma, an indispensable aid to researchers. Since 1967 the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN) has provided for co-ordination and liaison between countries to further the standardization of geographical names. To date eleven working sessions and four international conferences have been held. In most countries of the world there are institutes and centres for onomastic research, official bodies for the national standardization of place names, and names societies. -

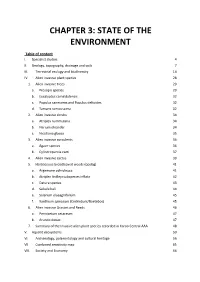

Chapter 3: State of the Environment

CHAPTER 3: STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT Table of content I. Specialist studies 4 II. Geology, topography, drainage and soils 7 III. Terrestrial ecology and biodiversity 14 IV. Alien invasive plant species 28 1. Alien invasive trees 29 a. Prosopis species 29 b. Eucalyptus camaldulensis 32 c. Populus canescens and Populus deltoides 32 d. Tamarix ramosissima 32 2. Alien invasive shrubs 34 a. Atriplex nummularia 34 b. Nerium oleander 34 c. Nicotiana glauca 35 3. Alien invasive succulents 36 a. Agave species 36 b. Cylindropuntia cacti 37 4. Alien invasive cactus 39 5. Herbaceous broadleaved weeds (opslag) 41 a. Argemone ochroleuca 41 b. Atriplex lindleyi subspecies inflata 42 c. Datura species 43 d. Salsola kali 44 e. Solanum elaeagnifolium 45 f. Xanthium spinosum (Cockleburr/Boetebos) 45 6. Alien invasive Grasses and Reeds 46 a. Pennisetum setaceum 47 b. Arundo donax 47 7. Summary of the Invasive alien plant species recorded in Karoo Central AAA 48 V. Aquatic ecosystems 50 VI. Archaeology, palaeontology and cultural heritage 56 VII. Combined sensitivity map 65 VIII. Society and Economy 66 SKA1_MID IEMP (2018) IX. Fundamental environmental principles 70 List of figures Figure 1: Karoo Supergroup sedimentary deposits ................................................................................. 8 Figure 2: Dolerite boulders in the SKA land core area ............................................................................ 9 Figure 3: Rainfall data for the Williston Spiral Arm .............................................................................. -

III~I~~~~~~~~~~~~34300004921619 Universiteit Vrystaat- Human and Social Capital Formation in South Africa's Arid Areas

.~:';-:;'=~:'I.f'",!;':!:",~.,Ifr,:,~:r ;Di~N!U~""",,,:,<:,,,,,,,,,,,,,~ ...~';;'~~J:·-:.:'J~~~~Ll 'li"yc'\-')n.,F: ,[:FS~:li'/ip) :\,,:;,.r.t 1\'; :,;,{~ ONDER iii' li "'L ..........._. ~!............oe. 1'_ • "-4'~._ ........ ~ .......... , 1.'(iEEN OlV(~jTl\NPlGHfTJ1:' urr DIE ~ ~ i University Free State ~ Lo:l:.._,':<'PLlr,T~:';:-l'•.. ..J I! Ln. .. .:"\. •\. r;:"'F:\'VP·[P;.-,n. ':..., .~ lj ~-,.. U10QD.. ~ re. ~IEJ, b:-.:~~.,~._..:~ ...........;..:~.~..::.~-r.-~:~~;t:.:r'?t.~,o!:.x. .....:~' III~I~~~~~~~~~~~~34300004921619 Universiteit Vrystaat- Human and social capital formation in South Africa's arid areas Mark Knightley Ingle Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the PhD degree in the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences Centre for Development Support at the University of the Free State. Submitted: 1 February 2012 Supervised by: Prof G.E. Visser I, Mark Ingle, declare that this dissertation/thesis hereby handed in for the PhD qualification at the University of the Free State, is my own independent work and that I have not previously submitted the same work for a qualification at/in another university/faculty . ......................................................................... 1 February 2012 I, Mark Ingle, hereby cede the copyright on this dissertation/thesis to the University of the Free State but only insofar as copyright on the previously published portions of it has not already been ceded to the publishing houses concerned . ....................................................................... 1 February 2012 Acknowiedgements: Without the encouragement and faith of my supervisor, Prof. Gustav Visser, and my wife, Prof. Doreen Atkinson, this body of work would never have been undertaken or brought to completion. My heartfelt thanks also to Profs. Lucius Rotes and Lochner Marais for their collegiality and support over last 10 years.