9 • the Reception of Ptolemy's Geography (End

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galileo's Misstatements About Copernicus Author(S): Edward Rosen Source: Isis, Vol

The History of Science Society Galileo's Misstatements about Copernicus Author(s): Edward Rosen Source: Isis, Vol. 49, No. 3 (Sep., 1958), pp. 319-330 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/226939 Accessed: 13/04/2010 16:29 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and The History of Science Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Isis. http://www.jstor.org Galileo's Misstatementsabout Copernicus By Edward Rosen * A RECENT English translation 1 of selections from the writings of Galileo ( (564-I642) will doubtless bring to the attention of many readers the statements about Copernicus (I473-I543) in the great Italian scientist's Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina. -

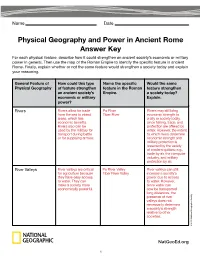

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Read Book a History of Contemporary Italy Society and Politics

A HISTORY OF CONTEMPORARY ITALY SOCIETY AND POLITICS, 1943-1988 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul Ginsborg | --- | --- | --- | 9781403961532 | --- | --- Origins of the Mafia - HISTORY Antonio Beccadelli combined the comic realism of Italian popular verse with the language of Martial to explore the underside of the early Renaissance. The richly illuminated small parchment codex bears witness to the musical interests of the cardinal, himself an avid singer. Federico Borromeo founded the Ambrosiana library, art collection, and academy in Milan. Sacred Painting laid out the rules that artists should follow when creating religious art. Humanist Tragedies offers a sampling of Latin drama from the Tre- and Quattrocento. These five tragedies— Ecerinis , Achilleis , Progne , Hyempsal , and Fernandus Servatus —were nourished by a potent amalgam of classical, medieval, and pre-humanist sources. Humanist tragedy testifies to momentous changes in literary conventions during the Renaissance. It contains a famous defense of the value of studying ancient pagan poetry in a Christian world. This first English translation includes the famous letter about the discovery on the Via Appia of the perfectly preserved body of a Roman girl. Lilio Gregorio Giraldi authored many works on literary history, mythology, and antiquities. The work gives a panoramic view of European poetry in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century, concentrating above all on Italy. Dialectical Disputations, Volume 1: Book I. Valla sought to replace the scholastic tradition of Aristotelian logic with a new logic based on the historical usage of classical Latin and on a commonsense approach. Marsilio Ficino , the Florentine scholar-philosopher-magus, was largely responsible for the Renaissance revival of Plato. -

The Vienna University Observatory

The Vienna University Observatory THOMAS POSCH Abstract The Vienna University Observatory, housing what was once the world’s largest refracting telescope, still serves as a centre of astronomical research and teaching. In 1819, Johann Josef von Littrow (1781-1840) became Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy at the University of Vienna. He tried to move the University Observatory - which was at that time still located at the city centre - to the outskirts, but did not succeed. After his death, his son Carl Ludwig von Littrow (1811-1877) became director of the Observatory. The total solar eclipse which took place on July 8, 1842, in his first year as director, made astronomy very popular and helped promote new investment. In 1872, a large site was acquired for a new observatory on a hill called "Türkenschanze", near the village of Währing outside Vienna. Building began in 1874. The architects of the imposing new building were Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer, both specialists in theatre buildings. Their concept was to combine observatory and apartments on a cross-shaped plan, which was unusually large for its day; 101 m length and 73 m width. The big refractor telescope (with an aperture of 27 inches, or 68 cm and a focal length of 10.5 m) was then the largest refracting telescope in the world. The celebratory opening took place in 1883. The excellent instrumentation made possible numerous remarkable Fig. 1 - Georg von Peuerbach’s ‘Theoricae novae planetarum’, discoveries in the fields of binary stars, Nuremberg 1473 asteroids and comets. However, the Währing district quickly became attractive to the Viennese upper classes and the observatory was soon part of an illuminated urban area. -

Джоð½ Зоñ€Ð½ ÐлÐ

Джон Зорн ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) The Big Gundown https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-big-gundown-849633/songs Spy vs Spy https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spy-vs-spy-249882/songs Buck Jam Tonic https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/buck-jam-tonic-2927453/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/six-litanies-for-heliogabalus- Six Litanies for Heliogabalus 3485596/songs Late Works https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/late-works-3218450/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/templars%3A-in-sacred-blood- Templars: In Sacred Blood 3493947/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/moonchild%3A-songs-without-words- Moonchild: Songs Without Words 3323574/songs The Crucible https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-crucible-966286/songs Ipsissimus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ipsissimus-3154239/songs The Concealed https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-concealed-1825565/songs Spillane https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spillane-847460/songs Mount Analogue https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mount-analogue-3326006/songs Locus Solus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/locus-solus-3257777/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/at-the-gates-of-paradise- At the Gates of Paradise 2868730/songs Ganryu Island https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ganryu-island-3095196/songs The Mysteries https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-mysteries-15077054/songs A Vision in Blakelight -

Conferencia Inaugural Keynote Address

CONFERENCIA INAUGURAL KEYNOTE ADDRESS LA HUELLA DE LA HISTORIA: LA SEVILLA AMERICANA THE FOOTPRINT OF HISTORY: THE AMERICAN SEVILLE Ramón María SERRERA, Catedrático de Historia de América. Universidad de Sevilla Professor of American History. University of Seville I agree with our mayor in that it has been a good decision to choose the city of Seville as the venue for this meeting. And this is not only because of what happened to me two days ago when I was consulting the Website of one of the leading tourist operators of the Anglo Saxon world, which defined Seville as follows: “Welcome to Seville, the capital of Andalusia, a region famous for its bullfights and its Flamenco dancers and sing- ers”. It is also because that for us, Sevillanos by birth, to live in this city is a dream. A dream that I would like to share with you as a professional historian. I have spent 40 years teaching the History of America and the same amount of time working in the document repository of the General Archive of the Indies. I therefore want to talk to you about the American Seville, i.e., the footprint that America has left on the art, architecture and urban development of Seville from the time of the discovery to the present. There are hundreds of American references in the city of Seville, some so forgotten that it is generally not known that the current head- quarters of the Comisiones Obreras trade union was previously the Church of San Miguel where Amerigo Vespucci was buried, the Church of La Magdalena was where Fray Bartolomé de las Casas was ordained, Calle Sierpes was the first Botanical Gar- Suscribo la afirmación de nuestro alcalde sobre el gran acierto que ha den with American plants, etc. -

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Roberto History 1964

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Umanesimo giuridico, giovinezza di history 1964/1965 Roberto Andrea Alciato George Eliot, the Florentine Abbott, Ruth literature 2016/2017 Renaissance, and the History of Scholarship Literary criticism of the Hungarian Acs, Pal literature 1993/1994 Renaissance Addona, Victoria art history 2015/2016 Dissemination of the Manner of the Adelson, Candace art history 1976/1977 1st School of Fontainebleau as evidenced in 16th-c Italian art The Bolognese villa in the age of Aksamija, Nadja art history 2012/2013 Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti I Disegni di Michelangelo per il Alberio, Elena art history 2017/2018 Cristo Risorto: Problemi di committenza e sviluppi iconografici Histoire de la dépose des peintures Albers, Geraldine art history 2001/2002 murales en Italie. Mémoire des lieux, voyage de oeuvres The humanist and his dog: the social and anthropological aspects of Almasi, Gabor literature 2006/2007 scholarly dogkeeping in the Italian Renaissance American Drawing, Renaissance Anania, Katie art history 2017/2018 Historiography, and The Remains of Humanism in the 1960s 1. A monograph on Giovanni Bellini 2. An exhibition on late Titian to Anderson, Jaynie art history 2000/2001 travel to Canberra and Melbourne, Australia A biography of Giovanni Morelli Anderson, Jaynie art history 2008/2009 (1816-1891) 'Florentinis ingeniis nihil ardui est': Andreoli, Ilaria art history 2011/2012 The Florentine Illustrated Book (1490-1550) Andreoni, Benedetto Varchi lettore di Dante e literature 2007/2008 Annalisa Petrarca all'Accademia Fiorentina The employment of 'religiosi' by Andrews, Frances history 2004/2005 governments of early Renaissance Italy Religion and Public Life in Late Andrews, Frances history 2010/2011 Medieval Italy Andrews, Noam history 2015/2016 Full Name Field Dates Project Title Genoese Galata. -

Kepler's Cosmological Synthesis

Kepler’s Cosmological Synthesis History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 39 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J. M. M. H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C. H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 20 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Kepler’s Cosmological Synthesis Astrology, Mechanism and the Soul By Patrick J. Boner LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Kepler’s Supernova, SN 1604, appears as a new star in the foot of Ophiuchus near the letter N. In: Johannes Kepler, De stella nova in pede Serpentarii, Prague: Paul Sessius, 1606, pp. 76–77. Courtesy of the Department of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Milton S. Eisenhower Library, Johns Hopkins University. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Boner, Patrick, author. Kepler’s cosmological synthesis: astrology, mechanism and the soul / by Patrick J. Boner. pages cm. — (History of science and medicine library, ISSN 1872-0684; volume 39; Medieval and early modern science; volume 20) Based on the author’s doctoral dissertation, University of Cambridge, 2007. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-24608-9 (hardback: alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-24609-6 (e-book) 1. Kepler, Johannes, 1571–1630—Philosophy. 2. Cosmology—History. 3. Astronomy—History. I. Title. II. Series: History of science and medicine library; v. 39. III. Series: History of science and medicine library. Medieval and early modern science; v. 20. QB36.K4.B638 2013 523.1092—dc23 2013013707 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. -

Curriculum Vitae June, 2021

Curriculum Vitae June, 2021 Assist. Prof. Sergio Angeli Affiliation Faculty of Science and Technology Free University of Bozen-Bolzano Piazza Università 1, 39100, Bolzano, Italy Email: [email protected] Current position Tenured Assistant Professor of General and Applied Entomology and Apiculture at the Faculty of Science and Technology, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Italy, since June 2009. Departmental and Institutional Coordinator for the Erasmus Programs for the Free University of Bozen- Bolzano, Italy with the promotion of 5 bilateral agreements: University of Göttingen (Germany), University of Cape Coast (Ghana), University of Chiang Mai (Thailand), Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (Sweden) and University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences of Vienna (Austria). Member of the Scientific Council of the PhD School “Mountain Environment and Agriculture”, Faculty of Science and Technology, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano (Italy) since 2009. Member of the Study Council of the Master Program “International Horticultural Science”, Join Master of the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano and the University of Bologna (Italy) since 2009. Member of the Municipal Council of Croviana, Trento province, Italy. Elected for the period 01/06/2010 - 01/06/2015, confirmed for the period 01/06/2015 - 20/10/2020 and for the period 20/10/2020 - 20/10/2025. Personal data Birthday: 11 July 1972; Place of birth: Cles (TN), Italy; Nationality: Italian; Marital status: married, 1 child. Education and Academic Career • Assistant Professor Department of Forest Zoology and Forest Conservation, Göttingen 2004 – 2009 (5 years) University, Germany. • Assistant Professor Institute of General and Systematic Zoology, Giessen University, 2002 – 2004 (2 years) Germany. -

Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Department Of

Basilios Bessarion Mystras 1436 Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 Università di Padova 1444 Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Vittorino da Feltre Marsilio Ficino Cristoforo Landino Università di Padova 1416 Università di Firenze 1462 Theodoros Gazes Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Angelo Poliziano Florens Florentius Radwyn Radewyns Geert Gerardus Magnus Groote Università di Mantova 1433 Università di Mantova Università di Firenze 1477 Constantinople 1433 DepartmentThe Mathematics Genealogy Project of is a serviceMathematics of North Dakota State University and and the American Statistics Mathematical Society. Demetrios Chalcocondyles http://www.mathgenealogy.org/ Heinrich von Langenstein Gaetano da Thiene Sigismondo Polcastro Leo Outers Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Rudolf Agricola Thomas von Kempen à Kempis Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Accademia Romana 1452 Université de Paris 1363, 1375 Université Catholique de Louvain 1485 Università di Firenze 1493 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1478 Mystras 1452 Jan Standonck Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Johannes von Gmunden Nicoletto Vernia Pietro Roccabonella Pelope Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Jean Tagault François Dubois Janus Lascaris Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Matthaeus Adrianus Alexander Hegius Johannes Stöffler Collège Sainte-Barbe 1474 Universität Basel 1477 Universität Wien 1406 Università di Padova Università di Padova Université Catholique de Louvain 1504, 1515 Université de Paris 1516 Università di Padova 1472 Università -

The LEGACY of CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS in the AMERICAS New Nations and a Transatlantic Discourse of Empire

The LEGACY of CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS in the AMERICAS New Nations and a Transatlantic Discourse of Empire Elise Bartosik-Vélez The Legacy of Christopher Columbus in the Americas The LEGACY of CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS in the AMERICAS New Nations and a Transatlantic Discourse of Empire Elise Bartosik-Vélez Vanderbilt University Press NASHVILLE © 2014 by Vanderbilt University Press Nashville, Tennessee 37235 All rights reserved First printing 2014 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file LC control number 2013007832 LC classification number e112 .b294 2014 Dewey class number 970.01/5 isbn 978-0-8265-1953-5 (cloth) isbn 978-0-8265-1955-9 (ebook) For Bryan, Sam, and Sally Contents Acknowledgments ................................. ix Introduction .......................................1 chapter 1 Columbus’s Appropriation of Imperial Discourse ............................ 15 chapter 2 The Incorporation of Columbus into the Story of Western Empire ................. 44 chapter 3 Columbus and the Republican Empire of the United States ............................. 66 chapter 4 Colombia: Discourses of Empire in Spanish America ............................ 106 Conclusion: The Meaning of Empire in Nationalist Discourses of the United States and Spanish America ........................... 145 Notes ........................................... 153 Works Cited ..................................... 179 Index ........................................... 195 Acknowledgments any people helped me as I wrote this book. Michael Palencia-Roth has been an unfailing mentor and model of Methical, rigorous scholarship and human compassion. I am grate- ful for his generous help at many stages of writing this manu- script. I am also indebted to my friend Christopher Francese, of the Department of Classical Studies at Dickinson College, who has never hesitated to answer my queries about pretty much any- thing related to the classical world.