018-245 ING Primavera CORR 24,5 X 29.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

(Exhibition Catalogue). Texts by Lucina Ward, James Lawrence and Anthony E Grudin

SOL LEWITT SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS AND EXHIBITION CATALOGUES 2018 American Masters 1940–1980 (exhibition catalogue). Texts by Lucina Ward, James Lawrence and Anthony E Grudin. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2018: 186–187, illustrated. Cameron, Dan and Fatima Manalili. The Avant-Garde Collection. Newport Beach, California: Orange County Museum of Art, 2018: 57, illustrated. Destination Art: 500 Artworks Worth the Trip. New York: Phaidon, 2018: 294, 374, illustrated. LeWitt, Sol. “Sol LeWitt: A Primary Medium.” In Auping, Michael. 40 Years: Just Talking About Art. Fort Worth, Texas and Munich: Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth; DelMonico BooksꞏPrestel, 2018: 84–87, illustrated. Picasso – Gorky – Warhol: Sculptures and Works on Paper, Collection Hubert Looser (exhibition catalogue). Edited by Florian Steininger. Krems an der Donau, Austria and Zürich: Kunsthalle Krems; Fondation Hubert Looser, 2018: 104, illustrated. Sol LeWitt: Between the Lines (exhibition catalogue). Texts by Francesco Stocchi. Rem Koolhaas and Adachiara Zevi. Milan: Fondazione Carriero, 2018 Sol LeWitt: Wall Drawings. Edited by Lindsay Aveilhé. [New York]: Artifex Press, 2018. 2017 Sol LeWitt: Selected Bibliography—Books 2 The Art Museum. London: Phaidon, 2017: 387, illustrated. Booknesses: Artists’ Books from the Jack Ginsberg Collection (exhibition catalogue). Johannesburg, South Africa: University of Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017: 129, 151, 221, illustrated. Delirious: Art at the Limits of Reason 1950–1980 (exhibition catalogue). Texts by Kelly Baum, Lucy Bradnock and Tina Rivers Ryan. New York: Met Breuer, 2017: pl.21, 22, 23, 24, illustrated. Doss, Erika. American Art of the 20th–21st Centuries. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017: fig. 113, p.178, illustrated. Gross, Béatrice. -

Donatello's Terracotta Louvre Madonna

Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Sandra E. Russell May 2015 © 2015 Sandra E. Russell. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning by SANDRA E. RUSSELL has been approved for the School of Art + Design and the College of Fine Arts by Marilyn Bradshaw Professor of Art History Margaret Kennedy-Dygas Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract RUSSELL, SANDRA E., M.A., May 2015, Art History Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning Director of Thesis: Marilyn Bradshaw A large relief at the Musée du Louvre, Paris (R.F. 353), is one of several examples of the Madonna and Child in terracotta now widely accepted as by Donatello (c. 1386-1466). A medium commonly used in antiquity, terracotta fell out of favor until the Quattrocento, when central Italian artists became reacquainted with it. Terracotta was cheap and versatile, and sculptors discovered that it was useful for a range of purposes, including modeling larger works, making life casts, and molding. Reliefs of the half- length image of the Madonna and Child became a particularly popular theme in terracotta, suitable for domestic use or installation in small chapels. Donatello’s Louvre Madonna presents this theme in a variation unusual in both its form and its approach. In order to better understand the structure and the meaning of this work, I undertook to make some clay works similar to or suggestive of it. -

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXX, 1, Winter 2019

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXX, 1, Winter 2019 An Affiliated Society of: College Art Association International Congress on Medieval Studies Renaissance Society of America Sixteenth Century Society & Conference American Association of Italian Studies President’s Message from Sean Roberts benefactors. These chiefly support our dissertation, research and publication grants, our travel grants for modern topics, February 15, 2019 programs like Emerging Scholars workshops, and the cost of networking and social events including receptions. The costs Dear Members of the Italian Art Society: of events, especially, have risen dramatically in recent years, especially as these have largely been organized at CAA and I have generally used these messages to RSA, usually in expensive cities and often at even more promote upcoming programing and events, to call expensive conference hotels. The cost of even one reception attention to recent awards, and to summarize all the in New York, for example, can quickly balloon to activities we regularly support. There are certainly no overshadow our financial support of scholarship. It will be a shortage of such announcements in the near future and significant task for my successor and our entire executive I’m certain that my successor Mark Rosen will have committee to strategize for how we might respond to rising quite a bit to report soon, including our speaker for the costs and how we can best use our limited resources to best 2019 IAS/Kress lecture in Milan. With the final of my fulfill our mission to promote the study of Italian art and messages as president, however, I wanted to address a architecture. -

VISITOR FIGURES 2015 the Grand Totals: Exhibition and Museum Attendance Numbers Worldwide

SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide VISITOR FIGURES 2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide THE DIRECTORS THE ARTISTS They tell us about their unlikely Six artists on the exhibitions blockbusters and surprise flops that made their careers U. ALLEMANDI & CO. PUBLISHING LTD. EVENTS, POLITICS AND ECONOMICS MONTHLY. EST. 1983, VOL. XXV, NO. 278, APRIL 2016 II THE ART NEWSPAPER SPECIAL REPORT Number 278, April 2016 SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES 2015 Exhibition & museum attendance survey JEFF KOONS is the toast of Paris and Bilbao But Taipei tops our annual attendance survey, with a show of works by the 20th-century artist Chen Cheng-po atisse cut-outs in New attracted more than 9,500 visitors a day to Rio de York, Monet land- Janeiro’s Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil. Despite scapes in Tokyo and Brazil’s economic crisis, the deep-pocketed bank’s Picasso paintings in foundation continued to organise high-profile, free Rio de Janeiro were exhibitions. Works by Kandinsky from the State overshadowed in 2015 Russian Museum in St Petersburg also packed the by attendance at nine punters in Brasilia, Rio, São Paulo and Belo Hori- shows organised by the zonte; more than one million people saw the show National Palace Museum in Taipei. The eclectic on its Brazilian tour. Mgroup of exhibitions topped our annual survey Bernard Arnault’s new Fondation Louis Vuitton despite the fact that the Taiwanese national muse- used its ample resources to organise a loan show um’s total attendance fell slightly during its 90th that any public museum would envy. -

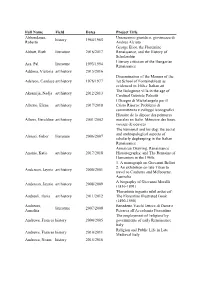

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Roberto History 1964

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Umanesimo giuridico, giovinezza di history 1964/1965 Roberto Andrea Alciato George Eliot, the Florentine Abbott, Ruth literature 2016/2017 Renaissance, and the History of Scholarship Literary criticism of the Hungarian Acs, Pal literature 1993/1994 Renaissance Addona, Victoria art history 2015/2016 Dissemination of the Manner of the Adelson, Candace art history 1976/1977 1st School of Fontainebleau as evidenced in 16th-c Italian art The Bolognese villa in the age of Aksamija, Nadja art history 2012/2013 Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti I Disegni di Michelangelo per il Alberio, Elena art history 2017/2018 Cristo Risorto: Problemi di committenza e sviluppi iconografici Histoire de la dépose des peintures Albers, Geraldine art history 2001/2002 murales en Italie. Mémoire des lieux, voyage de oeuvres The humanist and his dog: the social and anthropological aspects of Almasi, Gabor literature 2006/2007 scholarly dogkeeping in the Italian Renaissance American Drawing, Renaissance Anania, Katie art history 2017/2018 Historiography, and The Remains of Humanism in the 1960s 1. A monograph on Giovanni Bellini 2. An exhibition on late Titian to Anderson, Jaynie art history 2000/2001 travel to Canberra and Melbourne, Australia A biography of Giovanni Morelli Anderson, Jaynie art history 2008/2009 (1816-1891) 'Florentinis ingeniis nihil ardui est': Andreoli, Ilaria art history 2011/2012 The Florentine Illustrated Book (1490-1550) Andreoni, Benedetto Varchi lettore di Dante e literature 2007/2008 Annalisa Petrarca all'Accademia Fiorentina The employment of 'religiosi' by Andrews, Frances history 2004/2005 governments of early Renaissance Italy Religion and Public Life in Late Andrews, Frances history 2010/2011 Medieval Italy Andrews, Noam history 2015/2016 Full Name Field Dates Project Title Genoese Galata. -

The British Museum Annual Reports and Accounts 2019

The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 HC 432 The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed on 19 November 2020 HC 432 The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 © The British Museum copyright 2020 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as British Museum copyright and the document title specifed. Where third party material has been identifed, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/ofcial-documents. ISBN 978-1-5286-2095-6 CCS0320321972 11/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fbre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Ofce The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 Contents Trustees’ and Accounting Ofcer’s Annual Report 3 Chairman’s Foreword 3 Structure, governance and management 4 Constitution and operating environment 4 Subsidiaries 4 Friends’ organisations 4 Strategic direction and performance against objectives 4 Collections and research 4 Audiences and Engagement 5 Investing -

Hood M U S Eum O F A

H O O D M U S E U M O F A R T D A R T M O U T H C O L L E G E quarter y Spring/Summer 2011 Cecilia Beaux, Maud DuPuy Darwin (detail), 1889, pastel on warm gray paper laid down on canvas. Promised gift to the Hood Museum of Art from Russell and Jack Huber, Class of 1963. Jerry Rutter teaching with the Yale objects. H O O D M U SE U M O F A RT S TA F F Susan Achenbach, Art Handler Gary Alafat, Security/Buildings Manager Juliette Bianco, Acting Associate Director Amy Driscoll, Docent and Teacher Programs Coordinator Patrick Dunfey, Exhibitions Designer/Preparations Supervisor Rebecca Fawcett, Registrarial Assistant Nicole Gilbert, Exhibitions Coordinator Cynthia Gilliland, Assistant Registrar Katherine Hart, Interim Director and Barbara C. and Harvey P. Hood 1918 Curator of Academic Programming Deborah Haynes, Data Manager Alfredo Jurado, Security Guard L E T T E R F R O M T H E D I R E C T O R Amelia Kahl Avdic, Executive Assistant he Hood Museum of Art has seen a remarkable roster of former directors during Adrienne Kermond, Tour Coordinator the past twenty-five years who are still active and prominent members of the Vivian Ladd, Museum Educator T museum and art world: Jacquelynn Baas, independent scholar and curator and Barbara MacAdam, Jonathan L. Cohen Curator of emeritus director of the University of California Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific American Art Film Archive; James Cuno, director of the Art Institute of Chicago; Timothy Rub, Christine MacDonald, Business Assistant director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; Derrick Cartwright, director of the Seattle Nancy McLain, Business Manager Art Museum; and Brian Kennedy, president and CEO of the Toledo Museum of Art. -

Passepartour 2019

PASSEPARTOUR 2019 FIRENZE OLTRARNO THE KEYS OF ACCESSIBILITY Florence is a world heritage site and as such it must be accessible to all, without exclusion. Florence welcomes people with physical disabilities due to an abundance of pedestrian areas and accessible historical and artistic sites. It is also unde- niable that some routes of the city-center - similar to many other historical cities throughout the world - may present some difficulties for people using wheelchairs: for example narrow streets, tiny sidewalks that are not easily passable or not homogeneous pavement. To address this problem and provide information on which paths are the best to follow for people with physical disabilities, the Municipality of Florence in collaboration with Kinoa Srl have designed and published this Guide. The PASSEPARTOUR project is made up of four volumes, each describing four different tourist itineraries "without barriers". In addition, the guide provides a map of the historical city-center, highlighting all the areas that can be navigated with complete autonomy, or with the support of a helper. In addition, Kinoa has developed the navigation app Kimap, which acts as a companion tool to the guide for the mobility of disabled people. Kimap can be downloaded for free on every smartphone: the app shows the most accessible path to reach your desired destination and is constantly updated. We hope that this project will contribute to improve the tourist experi- ence for those visiting our marvellous City, opening the doors to its extraordinary heritage. Cecilia Del Re Councilor for Tourism of the City of Florence Florence is a world heritage site and as such it must be accessible to all, without exclusion. -

The Antiquarian and His Palazzo

THE ANTIQUARIAN AND HIS PALAZZO A case study of the interior of the Palazzo Davanzati in Florence R.E. van den Bosch The antiquarian and his palazzo A case study of the interior of the Palazzo Davanzati in Florence Student: R.E. (Romy) van den Bosch Student no.: s1746960 Email address: [email protected] First reader: Dr. E. Grasman Second reader: Prof. dr. S.P.M. Bussels Specialisation: Early modern and medieval art Academic year: 2018-2019 Declaration: I hereby certify that this work has been written by me, and that it is not the product of plagiarism or any other form of academic misconduct. Signature: ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the result of a long and intense process and it would not have been possible without the help and encouragement of a number of people. I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Edward Grasman. Thanks to his patience and guidance throughout this long process and the necessary steering in the right direction when I needed it, I can now finish this project. Secondly, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Paul van den Akker and Drs. Irmgard Koningsbruggen. My love for Florence began during a school excursion led by these two great teachers, who showed us the secret and not so secret places of Florence, and most importantly, introduced me to the Palazzo Davanzati. Finally, I must express my profound gratitude to my parents and my sister for their love, unfailing belief and continuous encouragement in me during this process, and to my friends, family and roommates, who picked me up when I had fallen down and constantly reminded me that I was able to finish this process. -

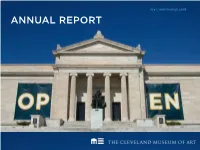

Annual Report

July 1, 2007–June 30, 2008 AnnuAl RepoRt 1 Contents 3 Board of Trustees 4 Trustee Committees 7 Message from the Director 12 Message from the Co-Chairmen 14 Message from the President 16 Renovation and Expansion 24 Collections 55 Exhibitions 60 Performing Arts, Music, and Film 65 Community Support 116 Education and Public Programs Cover: Banners get right to the point. After more than 131 Staff List three years, visitors can 137 Financial Report once again enjoy part of the permanent collection. 138 Treasurer Right: Tibetan Man’s Robe, Chuba; 17th century; China, Qing dynasty; satin weave T with supplementary weft Prober patterning; silk, gilt-metal . J en thread, and peacock- V E feathered thread; 184 x : ST O T 129 cm; Norman O. Stone O PH and Ella A. Stone Memorial er V O Fund 2007.216. C 2 Board of Trustees Officers Standing Trustees Stephen E. Myers Trustees Emeriti Honorary Trustees Alfred M. Rankin Jr. Virginia N. Barbato Frederick R. Nance Peter B. Lewis Joyce G. Ames President James T. Bartlett Anne Hollis Perkins William R. Robertson Mrs. Noah L. Butkin+ James T. Bartlett James S. Berkman Alfred M. Rankin Jr. Elliott L. Schlang Mrs. Ellen Wade Chinn+ Chair Charles P. Bolton James A. Ratner Michael Sherwin Helen Collis Michael J. Horvitz Chair Sarah S. Cutler Donna S. Reid Eugene Stevens Mrs. John Flower Richard Fearon Dr. Eugene T. W. Sanders Mrs. Robert I. Gale Jr. Sarah S. Cutler Life Trustees Vice President Helen Forbes-Fields David M. Schneider Robert D. Gries Elisabeth H. Alexander Ellen Stirn Mavec Robert W. -

Dresden – Where Opera Never Ends Let’S Go to the Museum

marketing.dresden.de Dresden Info Service Spring 2013 Dresden – Where Opera never ends Let’s go to the museum Dear friend of Dresden, Dresden sets new tourism record: in 2012, for the first time Dresden. Let’s go to the museum. 2 ever, overnight stays in Dresden broke the 4 million barrier. The Dresden State Art Collections – One reason for this is the top spot achieved by the city’s a world-class museum association. 3 hotels in the recent Trivago.com Reputation Ranking global survey: Dresden’s hotels have the most satisfied customers Richard Wagner’s 200th birthday in the world! And large numbers of these visitors discovered celebrated in museums . .4 for themselves the immeasurable riches in the city‘s 50 and Magnificent and brilliant. The SKD celebrate more museums. The State Art Collections alone welcomed two major openings in 2013 . 6 more than 2.5 million visitors in 2012. More than enough reason then for us to set out on the trail of Dresden’s leg- Oldest, youngest, largest, smallest – endary museums, where the passion for collecting and Dresden’s superlative museums . 7 displaying things of beauty is strikingly obvious, as are Don’t miss these! Exhibition highlights in 2013. .9 their ambitious, ground-breaking contemporary exhibition projects. The Dresden City Museum, the Book Museum Please touch the exhibits! in the Saxon State and University Library (SLUB), and the Interactive museum experience . 11 Wagner-Stätten-Graupa complete the harmonious circle of Dresden’s vibrant tradition. The 200th anniversary of Richard Wagner’s birth will be celebrated here, as it will be in the Semper Opera House, the Frauenkirche and concert Legal notice .