Angkor Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventaire-CIK-09042017.Pdf

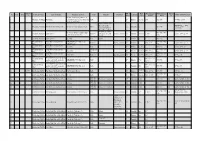

Autre(s) Nb de Date Estampages Estampages Autres K. Ext. Ind. Pays, province Lieu d’origine Situation actuelle Type Détails Matériau Langue Éditions/traductions n° lignes (śaka) EFEO BNF est. In situ ; dans la maçonnerie de 1 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Vat Thling l’autel de la pagode du village de Stèle 26 Khmer vie-viie 271 302 (34) - IC VI, p. 28-30 Lê Hoat, Châu Đốc Dalle formant seuil du tombeau du BEFEO XL, p. 480 2 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Phnom Svam ou Nui Sam In situ (en 1923, Cœdès 1923) Dalle 12 Sanskrit xe - 301 (34) - mandarin Nguyên (chronique) Ngoc Thoai ; Ruinée Trouvée sur l'allée In situ (en 2002), enchassé dans 303 (34) ; 471 3 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Linh Son Tu Piédroit principale de Linh Schiste ardoisier 11 Sanskrit vie-viie n. 295 - Cœdès 1936, p. 7-9 l'autel de Linh Son Tu (79) Son Tu 4 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Linh Son Tu Inconnue Stèle Ruinée 12 Khmer xe - 304 (34) - - Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram BTLSHCM 2893 (Kp 1, 2) ; 305 (69) ; 472 5 - - - Piédroit Schiste ardoisier 22 Sanskrit ve 329 ; n. 15 - Cœdès 1931, p. 1-7 Tháp Loveng BTLS 5964? (79) Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram 6 - - - Inconnue Stèle 10 Khmer vie-viie - 306 (34) - Cœdès 1936, p. 5 Tháp Loveng Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram Chapiteau 307 (34) ; 473 7 - - - Inconnue 20 Khmer vie-viie 331 ; n. 16 - Cœdès 1936, p. 3-5 Tháp Loveng (?) (79) Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram 308 (34) ; 474 8 - - - DCA 6811 Piédroit Schiste ardoisier 10 Khmer vie-viie 259 ; n. -

Tapas in the Rg Veda

TAPAS IN THE ---RG VEDA TAPAS IN THE RG VEDA By ANTHONY L. MURUOCK, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University April 1983 MASTER OF ARTS (1983) McMaster University (Religious Studies) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Tapas in the fuL Veda AUTHOR: Anthony L. Murdock, B.A. (York University) SUPERVISORS: Professor D. Kinsley Professor P. Younger Professor P. Granoff NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 95 ii ABSTRACT It is my contention in this thesis that the term tapas means heat, and heat only, in the Bi[ Veda. Many reputable scholars have suggested that tapas refers to asceticism in several instances in the RV. I propose that these suggestions are in fact unnecessary. To determine the exact meaning of tapas in its many occurrences in the RV, I have given primary attention to those contexts (i.e. hymns) in which the meaning of tapas is absolutely unambiguous. I then proceed with this meaning in mind to more ambiguous instances. In those instances where the meaning of tapas is unambiguous it always refers to some kind of heat, and never to asceticism. Since there are unambiguous cases where ~apas means heat in the RV, and there are no unambiguous instances in the RV where tapas means asceticism, it only seems natural to assume that tapas means heat in all instances. The various occurrences of tapas as heat are organized in a new system of contextual classifications to demonstrate that tapas as heat still has a variety of functions and usages in the RV. -

Cambodia-10-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Cambodia Temples of Angkor p129 ^# ^# Siem Reap p93 Northwestern Eastern Cambodia Cambodia p270 p228 #_ Phnom Penh p36 South Coast p172 THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Nick Ray, Jessica Lee PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Cambodia . 4 PHNOM PENH . 36 TEMPLES OF Cambodia Map . 6 Sights . 40 ANGKOR . 129 Cambodia’s Top 10 . 8 Activities . 50 Angkor Wat . 144 Need to Know . 14 Courses . 55 Angkor Thom . 148 Bayon 149 If You Like… . 16 Tours . 55 .. Sleeping . 56 Baphuon 154 Month by Month . 18 . Eating . 62 Royal Enclosure & Itineraries . 20 Drinking & Nightlife . 73 Phimeanakas . 154 Off the Beaten Track . 26 Entertainment . 76 Preah Palilay . 154 Outdoor Adventures . 28 Shopping . 78 Tep Pranam . 155 Preah Pithu 155 Regions at a Glance . 33 Around Phnom Penh . 88 . Koh Dach 88 Terrace of the . Leper King 155 Udong 88 . Terrace of Elephants 155 Tonlé Bati 90 . .. Kleangs & Prasat Phnom Tamao Wildlife Suor Prat 155 Rescue Centre . 90 . Around Angkor Thom . 156 Phnom Chisor 91 . Baksei Chamkrong 156 . CHRISTOPHER GROENHOUT / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / GROENHOUT CHRISTOPHER Kirirom National Park . 91 Phnom Bakheng. 156 SIEM REAP . 93 Chau Say Tevoda . 157 Thommanon 157 Sights . 95 . Spean Thmor 157 Activities . 99 .. Ta Keo 158 Courses . 101 . Ta Nei 158 Tours . 102 . Ta Prohm 158 Sleeping . 103 . Banteay Kdei Eating . 107 & Sra Srang . 159 Drinking & Nightlife . 115 Prasat Kravan . 159 PSAR THMEI P79, Entertainment . 117. Preah Khan 160 PHNOM PENH . Shopping . 118 Preah Neak Poan . 161 Around Siem Reap . 124 Ta Som 162 . TIM HUGHES / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / HUGHES TIM Banteay Srei District . -

Vietnam & Cambodia Asiana

Vietnam & Cambodia J-Term 2018-19 December 26th- January 20th 26th December 2018 : Travel Day Korean Airlines 094 Departing (IAD) Washington, DC Wed Dec 26 at 11:50 AM Arriving (ICN) Seoul, South Korea Thu Dec 27 at 04:30 PM Korean Airlines 679 Departing (ICN) Seoul, South Korea Thu Dec 27 at 06:40 PM Arriving (HAN) Hanoi, Vietnam Thu Dec 27 at 09:40 PM Korean Airlines 690 Departing (PNH) Phnom-Penh, Cambodia Korean Airlines 093 Departing (ICN) Seoul, South Korea Sun Jan 20 at 10:15 AM Arriving (IAD) Washington, DC Sun Jan 20 at 09:50 AM DAY 01 (27th DECEMBER 2018): HANOI ARRIVAL Upon your arrival at Noi Bai international airport, you are warmly welcome by Asiana Travel local guide and transfer to the hotel for check-in. You are free at your leisure for relaxing after the long time flight. Overnight at hotel in Hanoi. Distance: Noi Bai airport - hotel in Hanoi central is 30km and take 45 minute drive Meals included: None DAY 02 (28th DECEMBER 2018): HANOI FULL DAY CITY TOUR Today’s tour begins at 08:00. Set off on a full-day guided tour of Hanoi. Begin with a visit to West Lake to admire the sixth-century Tran Quoc Buddhist Pagoda. Next up is a short drive to visit to the famed Temple of Literature. Wander around this incredible compound which was constructed in 1076. Become fascinated with the stories of the building and get a glimpse of the past when it served as a university and temple. Afterward, head over to the Vietnam Museum of Ethnology (closed on Monday). -

3D Angkor Wat

3D ANGKOR WAT SINGAPORE - SIEM REAP (NO MEALS) DAY 1: Arrive at Siem Reap International Airport and transfer to the hotel In the morning, visit the ancient capital of Angkor Thom (12th century). See the South Gate with its huge statues depicting the churning of the ocean of milk, Bayon temple (unique for its 54 towers decorated with over 200 smiling faces of Avolokitesvara), Baphuon (recently re- opened after years of restoration), the Royal Enclosure, Phimeanakas, the Elephants Terrace, the Terrace of the Leper King. In the afternoon, visit Prasat Kravan with its unique brick sculptures and Srah Srang (“The Royal Baths”), undoubtedly used in the past for ritual bathing. Then visit the most famous of all the temples on the plain of Angkor: Angkor Wat. The temple complex covers 81 hectares and is comparable in size to the Imperial Palace in Beijing. Its distinctive five towers are emblazoned on the Cambodian flag and the 12th century masterpiece is considered by art historians to be the prime example of classical Khmer art and architecture. Angkor Wat’s five towers symbolize Meru’s five peaks - the enclosed wall represents the mountains at the edge of the world and the surrounding moat, the ocean beyond. Sunset at Angkor Wat. Overnight at the hotel. SIEM REAP (B) DAY 2: Breakfast at hotel. Continue to Banteay Srei temple (10th century), regarded as the jewel in the crown of classical Khmer art. Stop at a local village to visit families who are producing palm sugar. Visit Banteay Samre, one of the most complete complexes at Angkor due to restoration using the method of “anastylosis”. -

Temples Tour Final Lite

explore the ancient city of angkor Visiting the Angkor temples is of course a must. Whether you choose a Grand Circle tour or a lessdemanding visit, you will be treated to an unforgettable opportunity to witness the wonders of ancient Cambodian art and culture and to ponder the reasons for the rise and fall of this great Southeast Asian civili- zation. We have carefully created twelve itinearies to explore the wonders of Siem Reap Province including the must-do and also less famous but yet fascinating monuments and sites. + See the interactive map online : http://angkor.com.kh/ interactive-map/ 1. small circuit TOUR The “small tour” is a circuit to see the major tem- ples of the Ancient City of Angkor such as Angkor Wat, Ta Prohm and Bayon. We recommend you to be escorted by a tour guide to discover the story of this mysterious and fascinating civilization. For the most courageous, you can wake up early (depar- ture at 4:45am from the hotel) to see the sunrise. (It worth it!) Monuments & sites to visit MORNING: Prasats Kravan, Banteay Kdei, Ta Prohm, Takeo AFTERNOON: Prasats Elephant and Leper King Ter- race, Baphuon, Bayon, Angkor Thom South Gate, Angkor Wat Angkor Wat Banteay Srei 2. Grand circuit TOUR 3. phnom kulen The “grand tour” is also a circuit in the main Angkor The Phnom Kulen mountain range is located 48 km area but you will see further temples like Preah northwards from Angkor Wat. Its name means Khan, Preah Neak Pean to the Eastern Mebon and ‘mountain of the lychees’. -

A New Date for the Phnom Da Images and Its Implications for Early Cambodia

A New Date for the Phnom Da Images and Its Implications for Early Cambodia NANCY H. DOWLING SCHOLARS FAMILIAR WITH SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART HISTORY are well aware of a confusing chronology for early Cambodian sculpture. One reason for this situa tion is obvious. For nearly fifty years, Cambodian art history has been wed to the work of George Coedes. Praised as the dean of Southeast Asian history, he was a member of an elite group of French scholars who worked in Cambodia for decades before World War II. In 1944, he wrote Histoire ancienne des hats hindouses d'Extreme-Orient, in which he established a chronological framework for early Southeast Asian history based on an interplay of Chinese texts and indigenous inscriptions. Most Southeast Asian historians readily admit that "his book remains the basic source for early South East Asian history, and while much recent re search, based upon new inscriptional evidence or re-readings, modifies some of Coedes' specific conclusions, the structure remains his" (Brown 1996: 3). Such a singular dependency on Coedes had a stifling effect on Cambodian art history. When Jean Boisselier, carrying on the work of Philippe Stern and Gilberte de Coral-Remusat, made a comprehensive attempt to set in order Cambodian sculpture, the French art historian fitted the works of art into Coedes' ready made chronology. Unfortunately, this all happened as if it were preferable to adjust Cambodian sculpture to a preconceived notion of history rather than ques tioning the model. In this way, some basic mistakes have been made, and these seriously affect the chronology and interpretation of early Cambodian sculpture. -

Angkor Highlight (04 Nights / 05 Days)

(Approved By Ministry of Tourism, Govt. of India) Angkor Highlight (04 Nights / 05 Days) Routing: Arrival Siem Reap - Rolous Group – Small Circuit – Angkor Wat – Grand Circuit - Banteay Srei – Tonle Sap Lake - Siem Reap Day 01 : Arrival Siem Reap (D) Welcome to Siem Reap, Cambodia! Upon arrival at Siem Reap Airport, greeting by our friendly tour guide, then you will be transferred direct to check in at hotel (room may ready at noon). This afternoon, we drive to visit the Angkor National Museum, learn about “the Legend Revealed” and see how the Khmer Empire has been established during the golden period. Continue to visit the Killing Fields at Wat Thmey, get to know some information about Khmer Rouge Regime or called the year of Zero (1975 – 1979) where over 2 million of Khmer people has been killed. Next visit to Preah Ang Check Preah Angkor, the secret place where local people go praying for good luck or safe journey. Day 02 : Rolous Group – Small Circuit (B, L) In the morning – we drive to explore the Roluos group. The Roluos group lies 15km(10 miles) southwest of Siem Reap and includes three temples - Bakong, Prah Ko and Lolei - dating from the late 9th century and corresponding to the ancient capital of Hariharalaya, from which the name of Lolei is derived. Remains include 3 well-preserved early temples that venerated the Hindu gods. The bas-reliefs are some of the earliest surviving examples of Khmer art. Modern-day villages surround the temples. In the afternoon, we visit small circuit including the unique brick sculptures of Prasat Kravan, the jungle intertwined Ta Prohm, made famous in Angelina Jolie’s Tomb Raider movie. -

Culture & History Story of Cambodia

CHAM CULTURE & HISTORY STORY OF CAMBODIA FARINA SO, VANNARA ORN - DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA R KILLEAN, R HICKEY, L MOFFETT, D VIEJO-ROSE CHAM CULTURE & HISTORY STORYﺷﻤﺲ ISBN-13: 978-99950-60-28-2 OF CAMBODIA R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose Farina So, Vannara Orn - 1 - Documentation Center of Cambodia ζរចងាំ និង យុត្ិធម៌ Memory & Justice មជ䮈មណ䮌លឯក羶រកម្宻ᾶ DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA (DC-CAM) Villa No. 66, Preah Sihanouk Boulevard Phnom Penh, 12000 Cambodia Tel.: + 855 (23) 211-875 Fax.: + 855 (23) 210-358 E-mail: [email protected] CHAM CULTURE AND HISTORY STORY R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose Farina So, Vannara Orn 1. Cambodia—Law—Human Rights 2. Cambodia—Politics and Government 3. Cambodia—History Funding for this project was provided by the UK Arts & Humanities Research Council: ‘Restoring Cultural Property and Communities After Conflict’ (project reference AH/P007929/1). DC-Cam receives generous support from the US Agency for International Development (USAID). The views expressed in this book are the points of view of the authors only. Include here a copyright statement about the photos used in the booklet. The ones sent by Belfast were from Creative Commons, or were from the authors, except where indicated. Copyright © 2018 by R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose & the Documentation Center of Cambodia. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Destination: Angkor Archaeological Park the Complete Temple Guide

Destination: Angkor Archaeological Park The Complete Temple Guide 1 The Temples of Angkor Ak Yom The earliest elements of this small brick and sandstone temple date from the pre-Angkorian 8th century. Scholars believe that the inscriptions indicate that the temple is dedicated to the Hindu 'god of the depths'. This is the earliest known example of the architectural design of the 'temple-mountain', which was to become the primary design for many of the Angkorian period temples including Angkor Wat. The temple is in a very poor condition. Angkor Thom Angkor Thom ("Great City") was the last and most enduring capital city of the Khmer empire. It was established in the late 12th century by King Jayavarman VII. The walled and moated royal city covers an area of 9 km², within which are located several monuments from earlier eras as well as those established by Jayavarman and his successors. At the centre of the city is Jayavarman's state temple, the Bayon, with the other major sites clustered around the Victory Square immediately to the north. Angkor Thom was established as the capital of Jayavarman VII's empire, and was the centre of his massive building programme. One inscription found in the city refers to Jayavarman as the groom and the city as his bride. Angkor Thom is accessible through 5 gates, one for each cardinal point, and the victory gate leading to the Royal Palace area. Angkor Wat Angkor Wat ("City of Temples"), the largest religious monument in the world, is a masterpiece of ancient architecture. The temple was built by the Khmer King Suryavarman II in the early 12th century as his state temple and eventual mausoleum. -

Part I the Religions of Indian Origin

Part I The Religions of Indian Origin MRC01 13 6/4/04, 10:46 AM Religions of Indian Origin AFGHANISTAN CHINA Amritsar Kedamath Rishikesh PAKISTAN Badrinath Harappa Hardwar Delhi Indus R. NEPAL Indus Civilization BHUTAN Mohenjo-daro Ayodhya Mathura Lucknow Ganges R. Pushkar Prayag BANGLADESH Benares Gaya Ambaji I N D I A Dakshineshwar Sidphur Bhopal Ahmadabad Jabalpur Jamshedpur Calcutta Dwarka Dakor Pavagadh Raipur Gimar Kadod Nagpur Bhubaneswar Nasik-Tryambak Jagannath Puri Bombay Hyderabad Vishakhapatnam Arabian Sea Panaji Bay of Bengal Tirupati Tiruvannamalai-Kaiahasti Bangalore Madras Mangalore Kanchipuram Pondicherry Calicut Kavaratti Island Madurai Thanjavar Hindu place of pilgrimage Rameswaram Pilgrimage route Major city SRI LANKA The Hindu cultural region 14 MRC01 14 6/4/04, 10:46 AM 1 Hinduism Hinduism The Spirit of Hinduism Through prolonged austerities and devotional practices the sage Narada won the grace of the god Vishnu. The god appeared before him in his hermitage and granted him the fulfillment of a wish. “Show me the magic power of your Maya,” Narada prayed. The god replied, “I will. Come with me,” but with an ambiguous smile on his lips. From the shade of the hermit grove, Vishnu led Narada across a bare stretch of land which blazed like metal under the scorching sun. The two were soon very thirsty. At some distance, in the glaring light, they perceived the thatched roofs of a tiny village. Vishnu asked, “Will you go over there and fetch me some water?” “Certainly, O Lord,” the saint replied, and he made off to the distant group of huts. When Narada reached the hamlet, he knocked at the first door. -

Sathya Sai Vahini

Sathya Sai Vahini Stream of Divine Grace Sathya Sai Baba Contents Sathya Sai Vahini 5 Preface 6 Dear Seeker! 7 Chapter I. The Supreme Reality 10 Chapter II. From Truth to Truth 13 Chapter III. The One Alone 17 Chapter IV. The Miracle of Miracles 21 Chapter V. Basic Belief 24 Chapter VI. Religion is Experience 27 Chapter VII. Be Yourself 30 Chapter VIII. Bondage 33 Chapter IX. One with the One 36 Chapter X. The Yogis 38 Chapter XI. Values in Vedas 45 Chapter XII. Values in Later Texts 48 Chapter XIII. The Avatar as Guru 53 Chapter XIV. This and That 60 Chapter XV. Levels and Stages 63 Chapter XVI. Mankind and God 66 Chapter XVII. Fourfold Social Division 69 Chapter XVIII. Activity and Action 73 Chapter XIX. Prayer 77 Chapter XX. The Primal Purpose 81 Chapter XXI. The Inner Inquiry 88 Chapter XXII. The Eternal Truths 95 Chapter XXIII. Modes of Worship 106 Chapter XXIV. The Divine Body 114 Glossary 119 Sathya Sai Vahini SRI SATHYA SAI SADHANA TRUST Publications Division Prasanthi Nilayam - 515134 Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India STD: 08555 : ISD : 91-8555 Phone: 287375, Fax: 287236 Email: [email protected] URL www.sssbpt.org © Sri Sathya Sai Sadhana Trust, Publications Division, Prasanthi Nilayam P.O. 515 134, Anantapur District, A.P. (India.) All Rights Reserved. The copyright and the rights of translation in any language are reserved by the Publishers. No part, passage, text or photograph or Artwork of this book should be reproduced, transmitted or utilised, in original language or by translation, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or by any information, storage and retrieval system except with the express and prior permission, in writing from the Convener, Sri Sathya Sai Sadhana Trust, Publications Division, Prasanthi Nilayam (Andhra Pradesh) India - Pin Code 515 134, except for brief passages quoted in book review.