A Selective Study of the Art Songs of Franz Lehár Amy Nielsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neue Lieder Plus

Wo wir dich loben, wachsen neue Lieder plus Strube Edition ALPHABETISCHES VERZEICHNIS Accorde-nous la paix .............. 202 Christe, der du trägst Adieu larmes, peines .............. 207 die Sünd der Welt .................. 110 Aimer, c’est vivre .................... 176 Christ, ô toi qui portes Allein aus Glauben ................. 101 nos faiblesses ........................ 110 Allein deine Gnade genügt ....102 Christ, ô toi visage de Dieu .... 111 Alléluia, Venez chantons ........ 174 Christus, Antlitz Gottes ........... 111 Alles, was atmet .................... 197 Christus, dein Licht .................. 11 Amazing love ......................... 103 Christus, Gottes Lamm ............ 12 Amen (K) ............................... 104 Christus, höre uns .................... 13 An den Strömen von Babylon (K) ... 1 Christ, whose bruises An dunklen, kalten Tagen ....... 107 heal our wounds ................... 111 Anker in der Zeit ...................... 36 Con alegria, Atme in uns, Heiliger Geist ..... 105 chantons sans barrières ......... 112 Aube nouvelle dans notre nuit .. 82 Con alegria lasst uns singen ... 112 Auf, Seele, Gott zu loben ........ 106 Courir contre le vent ................. 40 Aus den Dörfern und aus Städten .. 2 Croix que je regarde ............... 170 Aus der Armut eines Stalles ........ 3 Danke für die Sonne .............. 113 Aus der Tiefe rufe ich zu dir ........ 4 Danke, Vater, für das Leben .... 114 Avec le Christ ........................... 70 Dans la nuit Bashana haba’a ..................... 183 la parole de Dieu (C) .............. 147 Behüte, Herr, Dans nos obscurités ................. 59 die ich dir anbefehle .............. 109 Das Leben braucht Erkenntnis .. 14 Bei Gott bin ich geborgen .......... 5 Dass die Sonne jeden Tag ......... 15 Beten .................................... 60 Das Wasser der Erde .............. 115 Bis ans Ende der Welt ................ 6 Da wohnt ein Sehnen Bist du mein Gott ....................... 7 tief in uns .............................. 116 Bist zu uns wie ein Vater ........... -

Canções E Modinhas: a Lecture Recital of Brazilian Art Song Repertoire Marcía Porter, Soprano and Lynn Kompass, Piano

Canções e modinhas: A lecture recital of Brazilian art song repertoire Marcía Porter, soprano and Lynn Kompass, piano As the wealth of possibilities continues to expand for students to study the vocal music and cultures of other countries, it has become increasingly important for voice teachers and coaches to augment their knowledge of repertoire from these various other non-traditional classical music cultures. I first became interested in Brazilian art song repertoire while pursuing my doctorate at the University of Michigan. One of my degree recitals included Ernani Braga’s Cinco canções nordestinas do folclore brasileiro (Five songs of northeastern Brazilian folklore), a group of songs based on Afro-Brazilian folk melodies and themes. Since 2002, I have been studying and researching classical Brazilian song literature and have programmed the music of Brazilian composers on nearly every recital since my days at the University of Michigan; several recitals have been entirely of Brazilian music. My love for the music and culture resulted in my first trip to Brazil in 2003. I have traveled there since then, most recently as a Fulbright Scholar and Visiting Professor at the Universidade de São Paulo. There is an abundance of Brazilian art song repertoire generally unknown in the United States. The music reflects the influence of several cultures, among them African, European, and Amerindian. A recorded history of Brazil’s rich music tradition can be traced back to the sixteenth-century colonial period. However, prior to colonization, the Amerindians who populated Brazil had their own tradition, which included music used in rituals and in other aspects of life. -

Deutsche Songs ( Nach Titel )

Deutsche Songs ( nach Titel ) 36grad 2raumwohnung '54, '74, '90, 2006 Sportfreunde Stiller '54, '74, '90, 2010 Sportfreunde Stiller 1 2 3 4 Heute Nacht da Feiern wir Anna Maria Zimmermann 1 Tag Seer, Die 1., 2., 3. B., Bela & Roche, Charlotte 10 kleine Jägermeister Toten Hosen, Die 10 Meter geh'n Chris Boettcher 10 Nackte Friseusen Mickie Krause 100 Millionen Volt Bernhard Brink 100.000 Leuchtende Sterne Anna Maria Zimmermann 1000 & 1 Nacht Willi Herren 1000 & 1 Nacht (Zoom) Klaus Lage Band 1000 km bis zum Meer Luxuslärm 1000 Liter Bier Chaos Team 1000 mal Matthias Reim 1000 mal geliebt Roland Kaiser 1000 mal gewogen Andreas Tal 1000 Träume weit (Tornero) Anna Maria Zimmermann 110 Karat Amigos, Die 13 Tage Olaf Henning 13 Tage Zillertaler Schürzenjäger, Die 17 Jahr, blondes Haar Udo Jürgens 18 Lochis, Die 180 grad Michael Wendler 1x Prinzen, Die 20 Zentimeter Möhre 25 Years Fantastischen Vier, Die 30.000 Grad Michelle 300 PS Erste Allgemeine Verunsicherung (E.A.V.) 3000 Jahre Paldauer, Die 32 Grad Gilbert 5 Minuten vor zwölf Udo Jürgens 500 Meilen Santiano 500 Meilen von zu Haus Gunter Gabriel 6 x 6 am Tag Jürgen Drews 60 Jahre und kein bisschen weise Curd Jürgens 60er Hitmedley Fantasy 7 Detektive Michael Wendler 7 Sünden DJ Ötzi 7 Sünden DJ Ötzi & Marc Pircher 7 Tage Lang (Was wollen wir trinken) Bots 7 Wolken Anna Maria Zimmermann 7000 Rinder Troglauer Buam 7000 Rinder Peter Hinnen 70er Kultschlager-Medley Zuckermund 75 D Leo Colonia 80 Millionen Max Giesinger 80 Millionen (EM 2016 Version) Max Giesinger 99 Luftballons Nena 99 Luftballons; -

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His Broadcasting Career Covers Both Radio and Television

557643bk VW US 16/8/05 5:02 pm Page 5 8.557643 Iain Burnside Songs of Travel (Words by Robert Louis Stevenson) 24:03 1 The Vagabond 3:24 The English Song Series • 14 DDD Iain Burnside enjoys a unique reputation as pianist and broadcaster, forged through his commitment to the song 2 Let Beauty awake 1:57 repertoire and his collaborations with leading international singers, including Dame Margaret Price, Susan Chilcott, 3 The Roadside Fire 2:17 Galina Gorchakova, Adrianne Pieczonka, Amanda Roocroft, Yvonne Kenny and Susan Bickley; David Daniels, 4 John Mark Ainsley, Mark Padmore and Bryn Terfel. He has also worked with some outstanding younger singers, Youth and Love 3:34 including Lisa Milne, Sally Matthews, Sarah Connolly; William Dazeley, Roderick Williams and Jonathan Lemalu. 5 In Dreams 2:18 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His broadcasting career covers both radio and television. He continues to present BBC Radio 3’s Voices programme, 6 The Infinite Shining Heavens 2:15 and has recently been honoured with a Sony Radio Award. His innovative programming led to highly acclaimed 7 Whither must I wander? 4:14 recordings comprising songs by Schoenberg with Sarah Connolly and Roderick Williams, Debussy with Lisa Milne 8 Songs of Travel and Susan Bickley, and Copland with Susan Chilcott. His television involvement includes the Cardiff Singer of the Bright is the ring of words 2:10 World, Leeds International Piano Competition and BBC Young Musician of the Year. He has devised concert series 9 I have trod the upward and the downward slope 1:54 The House of Life • Four poems by Fredegond Shove for a number of organizations, among them the acclaimed Century Songs for the Bath Festival and The Crucible, Sheffield, the International Song Recital Series at London’s South Bank Centre, and the Finzi Friends’ triennial The House of Life (Words by Dante Gabriel Rossetti) 26:27 festival of English Song in Ludlow. -

VOCAL 78 Rpm Discs Minimum Bid As Indicated Per Item

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs Minimum bid as indicated per item. Listings “Just about 1-2” should be considered as mint and “Cons. 2” with just the slightest marks. For collectors searching top copies, you’ve come to the right place! The further we get from the time of production (in many cases now 100 years or more), the more difficult it is to find such excellent extant pressings. Some are actually from mint dealer stocks and others the result of having improved copies via dozens of collections purchased over the past fifty years. * * * For those looking for the best sound via modern reproduction, those items marked “late” are usually of high quality shellac, pressed in the 1950-55 period. A number of items in this particular catalogue are excellent pressings from that era. * * * Please keep in mind that the minimum bids are in U.S. Dollars, a benefit to most collectors. * * * “Text label on verso.” For a brief period (1912-14), Victor pressed silver-on-black labels on the reverse sides of some of their single-faced recordings, usually with a translation of the text or similarly related comments. BESSIE ABOTT [s]. Riverdale, NY, 1878-New York, 1919. Following the death of her father which left her family penniless, Bessie and her sister Jessie (born Pickens) formed a vaudeville sister vocal act, accompanying themselves on banjo and guitar. Upon the recommendation of Jean de Reszke, who heard them by chance, Bessie began operatic training with Frida Ashforth. She subsequently studied with de Reszke him- self and appeared with him at the Paris Opéra, making her debut as Gounod’s Juliette. -

Mélodie French Art Song Recital; Wednesday, April 28, 2021

UCM Music Presents UCM Music Presents MÉLODIE FRENCH ART SONG RECITAL Dr. Stella D. Roden and Students MÉLODIE FRENCH ART SONG RECITAL Dr. Stella D. Roden and Students Hart Recital Hall Cynthia Groff, piano Hart Recital Hall Cynthia Groff, piano Wednesday, April 28, 2021 Denise Robinson, piano Wednesday, April 28, 2021 Denise Robinson, piano 7:00 p.m. 7:00 p.m. In consideration of the performers, other audience members, and the live recording of this concert, please In consideration of the performers, other audience members, and the live recording of this concert, please silence all devices before the performance. Parents are expected to be responsible for their children's behavior. silence all devices before the performance. Parents are expected to be responsible for their children's behavior. Le Charme Ernest Chausson (1855-1899) Le Charme Ernest Chausson (1855-1899) Lucas Henley, baritone Lucas Henley, baritone Les cygnes Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947) Les cygnes Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947) Anna Sanderson, soprano Anna Sanderson, soprano Lydia Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Lydia Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Alex Scharfenberg, tenor Alex Scharfenberg, tenor Ici-bas! Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Ici-bas! Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Gabrielle Moore, soprano Gabrielle Moore, soprano Fleur desséchée Pauline García Viardot (1821-1910) Fleur desséchée Pauline García Viardot (1821-1910) Janie Turner, soprano Janie Turner, soprano Le lever de la lune Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) Le lever de la lune Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) Nikolas Baumert, baritone Nikolas Baumert, baritone continued on reverse continued on reverse Become a Concert Insider! Text the word “concerts” to 660-248-0496 Become a Concert Insider! Text the word “concerts” to 660-248-0496 or visit ucmmusic.com to sign up for news about upcoming events. -

Podium Operette: Du Mein Schönbrunn

Podium Operette: Du mein Schönbrunn Kaiserin, Kaiser und Imperiales als Topoi der Wiener Operette Zum 300. Geburtstag Maria Theresias Universitätslehrgang Klassische Operette (Leitung: Wolfgang Dosch) Donnerstag, 11. Mai 2017 18.00 Uhr Musik und Kunst Privatuniversität der Stadt Wien MUK.podium Johannesgasse 4a, 1010 Wien PROGRAMM Leo Fall (1873, Olmütz – 1925, Wien) aus Die Kaiserin (Text: Julius Brammer/ Alfred Grünwald), 1915, Berlin Metropoltheater Wenn die Wiener Edelknaben Michiko Fujikawa, Sopran Nataliia Ulasevych, Sopran Jantus Philaretou, Bariton Wir sind drei feine Diplomaten Seungmo Jung, Tenor Wonbae Cho, Tenor Jantus Philaretou, Bariton Die Kaiserin: Original Klavierauszug Du mein Schönbrunn Adriana Hernandez Flores, Sopran Mir hat heute Nacht von ein’ Tanzerl geträumt Adriana Hernandes Flores, Sopran Jantus Philaretou, Bariton Ja, so singt man und tanzt man in Wien Nataliia Ulasevych, Sopran Seungmo Jeong, Tenor Fritzi Massary als Maria Theresia, UA Berlin 1915 2 Nico Dostal (1895, Korneuburg – 1981, Salzburg) aus Die ungarische Hochzeit (Text: Hermann Hermecke), 1939, Stuttgart Märchentraum der Liebe Wonbae Cho, Tenor Bruno Granichstaedten (1879, Wien – 1944, New York) aus Auf Befehl der Kaiserin (Text: Leopold Jacobson/ Robert Bodanzky), 1915, Wien Wann die Musik spielt Michiko Fujikawa, Sopran Nataliia Ulasevych, Sopran Seungmo Jeong, Tenor Dolores Schmidinger als Maria Theresia, Komm’, die Kaiserin will tanzen Die Ungarische Hochzeit, Lehár Festival Bad Ischl, 2015 © Foto Hofer Sonja Gebert, Sopran Branimir Agovi, Bariton -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Oscar Straus Beiträge Zur Annäherung an Einen Zu Unrecht Vergessenen

Fedora Wesseler, Stefan Schmidl (Hg.), Oscar Straus Beiträge zur Annäherung an einen zu Unrecht Vergessenen Amsterdam 2017 © 2017 die Autorinnen und Autoren Diese Publikation ist unter der DOI-Nummer 10.13140/RG.2.2.29695.00168 verzeichnet Inhalt Vorwort Fedora Wesseler (Paris), Stefan Schmidl (Wien) ......................................................................5 Avant-propos Fedora Wesseler (Paris), Stefan Schmidl (Wien) ......................................................................7 Wien-Berlin-Paris-Hollywood-Bad Ischl Urbane Kontexte 1900-1950 Susana Zapke (Wien) ................................................................................................................ 9 Von den Nibelungen bis zu Cleopatra Oscar Straus – ein deutscher Offenbach? Peter P. Pachl (Berlin) ............................................................................................................. 13 Oscar Straus, das „Überbrettl“ und Arnold Schönberg Margareta Saary (Wien) .......................................................................................................... 27 Burlesk, ideologiekritisch, destruktiv Die lustigen Nibelungen von Oscar Straus und Fritz Oliven (Rideamus) Erich Wolfgang Partsch† (Wien) ............................................................................................ 48 Oscar Straus – Walzerträume Fritz Schweiger (Salzburg) ..................................................................................................... 54 „Vm. bei Oscar Straus. Er spielte mir den tapferen Cassian vor; -

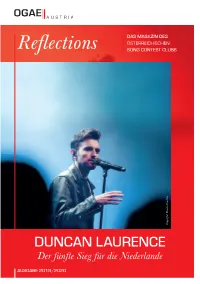

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

Early 20Th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: a Cosmopolitan Genre

This is a repository copy of Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/150913/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Scott, DB orcid.org/0000-0002-5367-6579 (2016) Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre. The Musical Quarterly, 99 (2). pp. 254-279. ISSN 0027-4631 https://doi.org/10.1093/musqtl/gdw009 © The Author 2016. Published by Oxford University Press. This is an author produced version of a paper published in The Musical Quarterly. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre Derek B. Scott In the first four decades of the twentieth century, new operettas from the German stage enjoyed great success with audiences not only in cities in Europe and North America but elsewhere around the world.1 The transfer of operetta and musical theatre across countries and continents may be viewed as cosmopolitanism in action. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated