Royal Engineers Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ankara Üniversitesi DİL VE TARİH COĞRAFYA Fakültesi Dergisi

D.T.C.F. Kütüphanesi Ankara Üniversitesi DİL VE TARİH COĞRAFYA Fakültesi Dergisi Cilt XX Sayı: 3-4 Temmuz - Aralık 1962 KIBRIS MÜŞAHEDELERİ1 Prof. Dr. Cevat R. GÜRSOY Bundan seksenbeş yıl önce Osmanlı İmparatorluğunun bir parçası iken, padişahın hükümranlık hakkı mahfuz kalmak üzere fiilî idaresi İngiltere'ye terkedilen, fakat 16 Ağustos 1960 tarihinden beri müstakil bir devlet haline gelmiş bulunan Kıbrıs adası, bugünün en çok ilgi toplayan konularından birini teşkil etmektedir. Muhtelif meslekten insanların gittikçe daha yakından meşgul olduğu bu eski yurt parçasına, ötedenberi Akdeniz memleketleri üzerinde: çalış tığımız için hususî bir alâka duymakta idik. Bu sebeple 1959 ve 1960 yaz tatillerinde Kıbrıs'a giderek onu yakından tanımaya karar verdik ve bütün adayı dolaşarak coğrafî müşahedeler yaptık. Bu müşahedelere imkân veren seyahatlerin yapılmasında maddî ve manevî müzaherette bulunmuş olan Fakültemiz Dekanlığı ile Ülkeler Coğrafyası Kürsü Profesörlüğüne, Kıbrıs Türk Kurumları Federasyonu Başkanlığına, Kıbrıs Türk Maarif Dairesi Müdür ve elemanlarına, orada yakın ilgilerini gördüğümüz eski ve yeni öğrencilerimize ve nihayet misafirperver Kıbrıslı Türk kardeşlerimize teşekkürü, yerine getirilmesi icabeden bir vazife sayarız. Kıbrıs hakkında yazılmış birçok eser ve makale vardır. Bunlar arasında seyahatnamelerle tarihi, siyasi, arkeolojik ve jeolojik çalışmalar zikredilmeye değer. 1929 senesinden evvel neşredilmiş olan 1500 den fazla eser, makale, 1) Türk Coğrafya Kurumu tarafından Konya'da tertip edilmiş olan XIII. Coğrafya Meslek Haftasında, 12 Kasım 1959 tarihinde verilen münakaşalı konferansın metni olup 1960 da ya pılan yeni müşahedelerle kısmen tadil ve tevsi edilmiştir. Ayrıca 1963 yılı Ocak ayında Alman ya'nın Hamburg Coğrafya Cemiyetinde, Kiel Üniversitesinde ve son olarak Samsun'da tertip edilen XV. Coğrafya Meslek Haftasında 1 Haziran 1963 tarihinde Kıbrıs hakkında konferanslar verilmiştir. -

UK Overseas Territories

INFORMATION PAPER United Kingdom Overseas Territories - Toponymic Information United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), also known as British Overseas Territories (BOTs), have constitutional and historical links with the United Kingdom, but do not form part of the United Kingdom itself. The Queen is the Head of State of all the UKOTs, and she is represented by a Governor or Commissioner (apart from the UK Sovereign Base Areas that are administered by MOD). Each Territory has its own Constitution, its own Government and its own local laws. The 14 territories are: Anguilla; Bermuda; British Antarctic Territory (BAT); British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT); British Virgin Islands; Cayman Islands; Falkland Islands; Gibraltar; Montserrat; Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands; Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha; South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands; Turks and Caicos Islands; UK Sovereign Base Areas. PCGN recommend the term ‘British Overseas Territory Capital’ for the administrative centres of UKOTs. Production of mapping over the UKOTs does not take place systematically in the UK. Maps produced by the relevant territory, preferably by official bodies such as the local government or tourism authority, should be used for current geographical names. National government websites could also be used as an additional reference. Additionally, FCDO and MOD briefing maps may be used as a source for names in UKOTs. See the FCDO White Paper for more information about the UKOTs. ANGUILLA The territory, situated in the Caribbean, consists of the main island of Anguilla plus some smaller, mostly uninhabited islands. It is separated from the island of Saint Martin (split between Saint-Martin (France) and Sint Maarten (Netherlands)), 17km to the south, by the Anguilla Channel. -

Joannou & Paraskevaides

Joannou & Paraskevaides International Building, Civil Engineering, Oil & Gas, Mechanical and Electrical Contractors List of Major Projects 2 3 4 Contents Offices 6 Introduction 7 The Ingredients of Sucess 8 List of Projects 9 Cyprus 13 Libya 27 Sultanate of Oman 55 Saudi Arabia 71 United Arab Emirates 87 Qatar 99 Iraq & Kurdistan 105 Greece 109 Algeria 125 Pakistan 129 Egypt 133 Ethiopia 137 Jordan 141 United States of America 145 6 Introduction Joannou & Paraskevaides (Overseas) Ltd, known as J&P, was established in 1961 in Guernsey, Channel Islands, United Kingdom. The Company’s forma- tion was an entrepreneurial move by the founders of Joannou & Paraskevaides Ltd., a successful construction company operating in Cyprus since 1941.The newly-formed international company grew steadily to become the dynamic organization it is today. After successfully completing its first overseas projects in North Africa in the 1960’s J&P rapidly expanded into the Gulf during the 1970’s. Over the next thirty years the Company broadened its operations throughout the world to become a global enterprise with a range of activities to meet the challenges of the industry. Today, J&P has a dynamic presence in the Middle East, Africa, the Asian Sub- continent and Europe. The core of the J&P Group’s operations is the Gulf Area and the GCC countries, with landmark projects in Saudi Arabia, the Sultanate of Oman, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, with regional offices in Riyadh, Jeddah, Muscat, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Doha. During the mid-1980’s the company entered the Oil & Gas sector and has since built an impressive portfolio of successfully completed projects in Libya, Saudi Arabia and Cyprus in the upstream and downstream sectors, as well as in power generation. -

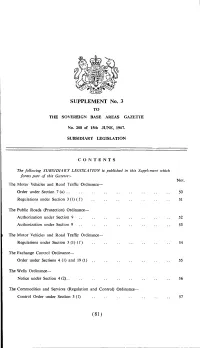

SUPPLEMENT No. 3 (81 )

SUPPLEMENT No. 3 TO THE SOVEREIGN BASE AREAS GAZETTE No. 208 of 15th JUNE, 1967. SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION CONTENTS The following SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION is published in this Supplement which forms part of this Gazette:- Not. The Motor Vehicles and Road Traffic Ordinance Order under Section 7 (a) .. 50 Regulations under Section 3 (1) (f) 51 The Public Roads (Protection) Ordinance Authorization under Section 9 52 Authorization under Section 9 53 The Motor Vehicles and Road Traffic Ordinance Regulations under Section 3 (1) (f) 54 The Exchange Control Ordinance- Order under Sections 4 (1) and 19 (1) 55 The Wells Ordinance- Notice under Section 4 (2).. 56 The Commodities and Services (Regulation and Control) Ordinance Control Order under Section 3 (I) 57 (81 ) 82 No. 50 THE MOTOR VEHICLES AND ROAD TRAFFIC ORDINANCE (Cap. 332 - Laws of Cyprus - and Ordinances 6 of 1961, 15 of 1962, 11 of 1965 and 4 of 1966) ORDER MADE UNDER SECTION 7A. In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by subsection (I) of section 7A of the Motor Vehicles and Road Traffic Ordinance and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, the Administrator hereby makes the following Order:- 1. This Order may be cited as the Speed Limits Order, 1967. 2. The roads, or parts of roads, set out in the first column of the Schedule hereto shall be subject to the respective maximum speed limits set out in the second column in the said Schedule. 3. For the purposes of this Order, the map references shown in the first column of Parts I and II of the Schedule hereto are references to the Town Plans Cyprus Map, Series K 912, Sheet Episkopi Cantonment and Sheet Dhekelia Cantonment, Edition I- GSGS, scale 1:5,000. -

Urzędowy Wykaz Nazw Państw I Terytoriów Niesamodzielnych

85=ĉ'2:Y:<.$Z UR 1$=:P$ē67: =ĉ'2: Y :<.$ ,7ERY72RIÓ: Z 1$=: 1,(6$02'=,(/1<&H P $ē67:,7( RY 725,Ï:1,(6$02'=,(/1<&+ 9 ISBN 978-83-254-2571-5 GŁÓWNY URZĄD GEODEZJI I KARTOGRAFII Warszawa 2019 GGUGiKUGiK 22019_Urzedowy019_Urzedowy wwykaz_polskiykaz_polski ookladka_druk.inddkladka_druk.indd 1 22019-10-31019-10-31 009:36:199:36:19 KOMISJA STANDARYZACJI NAZW GEOGRAFICZNYCH POZA GRANICAMI RZECZYPOSPOLITEJ POLSKIEJ przy Głównym Geodecie Kraju URZĘDOWY WYKAZ NAZW PAŃSTW I TERYTORIÓW NIESAMODZIELNYCH Wydanie V zaktualizowane GŁÓWNY URZĄD GEODEZJI I KARTOGRAFII Warszawa 2019 KOMISJA STANDARYZACJI NAZW GEOGRAFICZNYCH POZA GRANICAMI RZECZYPOSPOLITEJ POLSKIEJ przy Głównym Geodecie Kraju Ewa Wolnicz-Pawłowska (przewodnicząca), Andrzej Markowski (zastępca przewodniczącej), Maciej Zych (zastępca przewodniczącej), Justyna Kacprzak (sekretarz); Teresa Brzezińska-Wójcik, Andrzej Czerny, Romuald Huszcza, Sabina Kacieszczenko, Dariusz Kalisiewicz, Artur Karp, Jerzy Ostrowski, Jarosław Pietrow, Jerzy Pietruszka, Andrzej Pisowicz, Bogumiła Więcław, Tomasz Wites, Wojciech Włoskowicz, Bogusław R. Zagórski Opracowanie Andrzej Czerny, Maciej Zych Konsultacja językowa Andrzej Markowski, Ewa Wolnicz-Pawłowska Współpraca Ministerstwo Spraw Zagraniczych (akceptacja polskich nazw państw i terytoriów) Zespół Ortografi czno-Onomastyczny Rady Języka Polskiego PAN (ustalenie przymiotników oraz nazw obywateli i mieszkańców) © Copyright by Główny Geodeta Kraju 2019 ISBN 978-83-254-2571-5 Łamanie komputerowe i druk Ofi cyna Drukarska Jacek Chmielewski ul. Sokołowska 12a, 01-142 Warszawa Spis treści Od Wydawcy . V Wprowadzenie . VII Przyjęte zasady latynizacji z języków posługujących się niełacińskimi systemami zapisu . XIII Objaśnienie skrótów i znaków . XVI Część I. Państwa . 1 Część II. Terytoria niesamodzielne . 45 Przynależność polityczna terytoriów niesamodzielnych . 60 Załącznik: Terytoria o nieustalonym lub spornym statusie międzynarodowym oraz inne . 63 Skorowidz nazw . -

Alex Bridgeman a Abidjan a Buja a Ccra a Dam Stow N a Lo Fi a Ndorra La

h e t s n a C t i s e n ş A a r i a n r B n e ă a u a e r l i i l l v l e a o B Alex Bridgeman u j V m e n C l a A a m l A o B e c a o p t r k t p r i b a o a o l u n r d i r a n u n A h g A T n s C B h o a g w i B s fi a h n o b k l s a e e t A i k n r a t s C A w a n o a s C B n w g m a e o i t s a k B s s r r a a i y m u r s a e a d S c A a A r r s B a C t a a d r o C n a a n p a r z a e c z B n b E i o j u D t E c i a s d a h i e v n S b i A A a l a u D i i n r r l e g o g s D r l v d B h e C e o u A e e o n n a k S b m c j a n u e a i E a h ó b a m B a t C p k n A u C f a B j i u s o o A h t m v jan b u k on ro h a o i D u o rua bid D ra Bak u Ca A g A B p C r o i u h C b a a n i n m d t a o E a n l D m a S o e t u n s n g t e e l r a m a s n D E o d t i n n a D b u C u s i u r a r F a r b a l H i t r F a b p e i G g r r t e u e f c t a o l h o n w i s u k i n n F a o o s H D f E i n a G a n F m n p v u a t r H w a w h y n E o n o D e t t a t v a D e f S e i u u g e k e h r v t s r h e g i e a r o n r F n a n u be Dak e Sea dinb n F s E D G E o F t l H i F i a r t m r e u a g e f e t H a G o i n s w u a u n a n F w t e o m F T n u a e e w l n a h o g a t r H f C T e o u e , e i e t r t l e i y s F G i u n g F k a F i H F r F ti G H e e fu to a G e w n u on H n Fu sta or o ña vi ab nia åt Fun wn a G ra Hag afuti F Freeto G H Alex Bridgeman Eye Nose Mouth AAbidjan Abuja Accra Adamstown Alofi Andorra la Vella Antananarivo Apia Ashgabat Asmara Astana Asunción Avarua AAbidjan Abuja Accra Adamstown Alofi Andorra la Vella Antananarivo Apia -

The World Factbook Appendix F :: Cross-Reference

The World Factbook Appendix F :: Cross-Reference List of Geographic Names Entry in The World Latitude Longitude Name Factbook (deg min) (deg min) Abidjan (capital) Cote d'Ivoire 5 19 N 4 02 W Abkhazia (region) Georgia 43 00 N 41 00 E Abu Dhabi (capital) United Arab Emirates 24 28 N 54 22 E Abu Musa (island) Iran 25 52 N 55 03 E Abuja (capital) Nigeria 9 12 N 7 11 E Abyssinia (former name for Ethiopia) Ethiopia 8 00 N 38 00 E Acapulco (city) Mexico 16 51 N 99 55 W Accra (capital) Ghana 5 33 N 0 13 W Adamstown (capital) Pitcairn Islands 25 04 S 130 05 W Addis Ababa (capital) Ethiopia 9 02 N 38 42 E Adelie Land (claimed by France; also Terre Antarctica 66 30 S 139 00 E Adelie) Aden (city) Yemen 12 46 N 45 01 E Aden, Gulf of Indian Ocean 12 30 N 48 00 E Admiralty Island United States (Alaska) 57 44 N 134 20 W Admiralty Islands Papua New Guinea 2 10 S 147 00 E Adriatic Sea Atlantic Ocean 42 30 N 16 00 E Adygey (region) Russia 44 30 N 40 10 E Aegean Islands Greece 38 00 N 25 00 E Aegean Sea Atlantic Ocean 38 30 N 25 00 E Afars and Issas, French Territory of the (or Djibouti 11 30 N 43 00 E FTAI; former name for Djibouti) Afghanestan (local name for Afghanistan) Afghanistan 33 00 N 65 00 E Agalega Islands Mauritius 10 25 S 56 40 E Agana (city; former name for Hagatna) Guam 13 28 N 144 45 E Ajaccio (city) France (Corsica) 41 55 N 8 44 E Ajaria (region) Georgia 41 45 N 42 10 E Akmola (city; former name for Astana) Kazakhstan 51 10 N 71 30 E Aksai Chin (region) China (de facto), India (claimed) 35 00 N 79 00 E Al Arabiyah as Suudiyah (local name -

The World Factbook Europe :: Dhekelia (UK Sovereign Base Area

The World Factbook Europe :: Dhekelia (UK sovereign base area) Introduction :: Dhekelia Background: By terms of the 1960 Treaty of Establishment that created the independent Republic of Cyprus, the UK retained full sovereignty and jurisdiction over two areas of almost 254 square kilometers - Akrotiri and Dhekelia. The larger of these is the Dhekelia Sovereign Base Area, which is also referred to as the Eastern Sovereign Base Area. Geography :: Dhekelia Location: Eastern Mediterranean, on the southeast coast of Cyprus near Famagusta Geographic coordinates: 34 59 N, 33 45 E Map references: Europe Area: total: 130.8 sq km country comparison to the world: 223 note: area surrounds three Cypriot enclaves Area - comparative: about three-quarters the size of Washington, DC Land boundaries: total: 103 km (approximately) border countries: Cyprus 103 km (approximately) Coastline: 27.5 km Climate: temperate; Mediterranean with hot, dry summers and cool winters Environment - current issues: netting and trapping of small migrant songbirds in the spring and autumn Geography - note: British extraterritorial rights also extended to several small off-post sites scattered across Cyprus; of the Sovereign Base Area land 60% is privately owned and farmed, 20% is owned by the Ministry of Defense, and 20% is SBA Crown land People and Society :: Dhekelia Languages: English, Greek Population: approximately 15,700 live on the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia including 7,700 Cypriots, 3,600 service and UK based contract personnel, and 4,400 dependents -

Countries & Their Capitals

COUNTRIES & THEIR CAPITALS Country Capital Afghanistan Kabul Akrotiri Episkopi Cantonment; also serves as capital of Dhekelia Albania Tirana Algeria Algiers American Samoa Pago Pago Andorra Andorra la Vella Angola Luanda Anguilla The Valley Antigua and Saint John's (Antigua) Barbuda Argentina Buenos Aires Armenia Yerevan Aruba Oranjestad Australia Canberra Austria Vienna Azerbaijan Baku (Baki) Bahamas, The Nassau Bahrain Manama Bangladesh Dhaka Barbados Bridgetown Belarus Minsk Belgium Brussels Belize Belmopan Benin Porto-Novo is the official capital; Cotonou is the seat of government Bermuda Hamilton Bhutan Thimphu Bolivia La Paz (seat of government); Sucre (legal capital and seat of judiciary) Bosnia and Sarajevo Herzegovina Botswana Gaborone Brazil Brasilia British Virgin Road Town Islands Brunei Bandar Seri Begawan Bulgaria Sofia Burkina Faso Ouagadougou Burma Rangoon (government refers to capital as Yangon) note: junta began shifting seat of government to Pyinmana area of central Burma in November 2005 Burundi Bujumbura Cambodia Phnom Penh Cameroon Yaounde Canada Ottawa Cape Verde Praia Cayman Islands George Town (Grand Cayman) Central African Bangui Republic Chad N'Djamena Chile Santiago China Beijing Christmas Island The Settlement Cocos (Keeling) West Island Islands Colombia Bogota Comoros Moroni Congo, Democratic Kinshasa Republic of the Congo, Republic Brazzaville of the Cook Islands Avarua Costa Rica San Jose Cote d'Ivoire Yamoussoukro; note - although Yamoussoukro has been the official capital since 1983, Abidjan remains the -

Reinterpreting Macmillan's Cyprus Policy, 1957-19601

Reinterpreting Macmillan’s Cyprus Policy, 1957-1960 1 ANDREKOS VARNAVA Abstract Commentators universally accept that successive British Governments wanted sovereignty over Cyprus until Harold Macmillan became Prime Minister in January 1957 who then decided to relinquish Cyprus. This assertion is made because the Macmillan Government had determined that the whole of Cyprus was not needed as a base and that bases in Cyprus were sufficient for British military purposes. The Macmillan Government’s plans for a solution, however, never included the complete withdrawal of British sovereignty over the island. Ultimately, Britain was not involved in terminating its colonial rule over Cyprus and was indeed reluctant to accept independence as a solution. By tracing the development of the concept of sovereign enclaves, a gap in the published historiography will be filled, while also answering what it was that made sovereignty over Cyprus so vital to British defence policy. The establishment of Sovereign Base Areas on the island questions the view that Cyprus was “relinquished”, let alone “decolonised”. The delay between the signing of the Zurich-London Accords and Cypriot independence, blamed on Makarios’ uncompromising attitude towards British military needs, will be reviewed. This article is a reinterpretation of the Macmillan Government’s Cyprus policy. Keywords: Cyprus, Harold Macmillan, Sovereignty, Decolonisation, Sovereign Bases Areas In January 1957, Harold Macmillan succeeded Anthony Eden as Prime Minister of Great Britain with British prestige in the Middle East at its lowest ebb. Eden’s government Suez escapade had left his government paralysed in the Middle East and Eden a shattered man. He had presided over one of the great British military fiascos and had also damaged Anglo-American relations. -

Seznam Států Světa

NEZÁVISLÉ STÁTY A ZÁVISLÁ ÚZEMÍ (2009) Kābul [ ] / Kābol [ ] republika (y) ﮐﺎﺑﻞ AFGHÁNISTÁN ĴýûIJ Islámská republika Afghánistán unitární stát ĀŅ9ŀĿĹć ńĸпĔ/ 7 IûĂĕĻûĪĬ/ 7 paštština [dә Afġānistān Islāmī Jumhūrīyat] darí (lokální název pro perštinu) ﲨﻬﻮﺭﯼ ﺍﺳﻼﻣﯽ ﺍﻓﻐﺎﻧﺴﺘﺎﻥ [Jomhūrī-ye Eslāmī-ye Afġānestān] ALBÁNIE Tiranë (Tirana) republika (*) Albánská republika unitární stát Republika e Shqipërisë albánština ALŽÍRSKO al-Jazā'ir [đù/ĒĈĵ/] republika (y) Dzayer / ⴷⵣⴰ ⵢ ⴻⵔ (Alžír) Alžírská lidová demokratická republika unitární stát ÿņþħĘĵ/ ÿņĠ/đİĹŅďĵ/ ÿŅđù/ĒĈĵ/ ÿŅ9ŀĿĹĈĵ/ arabština (úřední jazyk) [Al Jumhūrīyah al Jazā’irīyah ad Dīmuqrāţīyah ash Sha’bīyah] Tagduda tamegdayt taɣerfant n Dzayer berberština (tamazight, národní jazyk) / ⵜⴰⴳⴷⵓⴷⴰ ⵜⴰⵎⴻⴳⴷⴰⵢⵜ ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴰⵏⵜ ⵏ ⴷⵣⴰⵢⴻⵔ ANDORRA Andorra la Vella nezávislý stát, spoluknížectví* Andorrské knížectví unitární stát Principat d'Andorra katalánština * státní forma je spoluknížectví pod nominální společnou správou francouzského prezidenta a biskupa v La Seu d'Urgell (Španělsko) ANGOLA Luanda republika (*y) Angolská republika unitární stát República de Angola portugalština ANTIGUA A BARBUDA St John's monarchie (*), království (S) Stát Antigua a Barbuda unitární stát State of Antigua and Barbuda angličtina (má dependence) od území státu jsou administrativně odděleny dvě dependence: Barbuda (Codrington) částečně samosprávná dep. Barbuda Barbuda angličtina Redonda (neobydlené území) dependence Redonda Redonda angličtina ARGENTINA Buenos Aires republika (y) Argentinská republika federativní stát / Argentinský -

Thanksgiving Menu 2010

Chef-d'oeuvre A Dinner of Dessert Thanksgiving 2010 Guest of Honor : David Shapiro A Menu Poem Chef-d'oeuvre A Dinner of Dessert by Geoffrey Gatza Copyright © 2010 Published by BlazeVOX [books] All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the publisher’s written permission, except for brief quotations in reviews. Printed in the United States of America Book design by Geoffrey Gatza First Edition BlazeVOX [books] 303 Bedford Ave Buffalo, NY 14216 [email protected] \ publisher of weird little books BlazeVOX [ books ] blazevox.org 2 4 6 8 0 9 7 5 3 1 A Dinner Menu of Dessert Amuseé New York State Sparkling Wine With A Gingered Chrysanthemum Flower Appetizer A Mixed Grill Of Sugared Papaya, Lychee And Caramel Banana Soup Deep Chocolate And Tarragon Soup With Frothed Coffee Cream And Hazelnuts Pièces Montées Chocolate Sculpture Of A Stuffed Turkey With Marshmallow Stuffing Desserts From Around The World Sour Cherry, Vanilla, Fig, Almond And Walnut Glyka Firnee With Pistachios And Flavored With Cardamom. Coconut Puff Cookies Coconut Pudding Flavored With Clove And Ground Excellence Scottish Black Bun Mango, Banana, Strawberry, Sweet Potato, And Chestnut Mochi Canned Peaches Cheese, Port & Exotic Nuts Dessert The Best Rice Pudding In The World Table of Contents The Big Story ................................................................................................................................................................................11 One Game of Scrabble .................................................................................................................................................................13