Cinema Became a Se

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Govind Nihalani's 'Hazaar Chaurasi Ki

Reclaiming Her /histories), reclaiming Lives: Govind Nihalani’s ‘Hazaar Chaurasi ki Ma’ and Mahashweta Devi’s Mother of 1084. Baruah Baishali Assistant Professor. Dept. of English Satyawati College (D) University of Delhi India Mahashweta Devi’s story is about the reawakening of a mother proselytized by the death of her son against the backdrop of the systematic “annihilation” of the Naxalites in the 1970’s Bengal. The uncanny death forces the apolitical mother to embark on a quest for the discovery of her ‘real’ son which eventually leads to her own self-discovery. The discovery entails the knowledge of certain truths or half truths about the particular socio-political milieu in which the characters are located. Sujata conditioned to play the submissive, unquestioning wife and mother for the major part of her life gains a new consciousness about her own reality (as a woman) and her immediate context (the patriarchal / feudal order). She therefore pledges to refashion herself by assimilating her son’s political beliefs of ushering in a new egalitarian world without centre or margin. In Govind Nihalani’s own words his film is “a tribute to that dream”. The symbiotic relation of the mother and the son which is shown to be more than just blood relation is done full justice by Nihalani. Jaya Bacchan plays to the hilt the traumatized mother (Sujata) who finds herself locked within her “solitary cell” and constantly assailed by the guilt of not knowing her son adequately when alive. The information about her son (Brati) that surfaces by her association with one Somu’s mother (Seema Biswas) and Nandini (played by Nandita Das) help her discover Brati his idealism, and shed her complacency about the arrangements of the hierarchised structure that underline every interpersonal (man- woman) and social (class/caste) relationship. -

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber TAILORING EXPECTATIONS How film costumes become the audience’s clothes ‘Bollywood’ film costume has inspired clothing trends for many years. Female consumers have managed their relation to film costume through negotiations with their tailor as to how film outfits can be modified. These efforts have coincided with, and reinforced, a semiotic of female film costume where eroticized Indian clothing, and most forms of western clothing set the vamp apart from the heroine. Since the late 1980s, consumer capitalism in India has flourished, as have films that combine the display of material excess with conservative moral values. New film costume designers, well connected to the fashion industry, dress heroines in lavish Indian outfits and western clothes; what had previously symbolized the excessive and immoral expression of modernity has become an acceptable marker of global cosmopolitanism. Material scarcity made earlier excessive costume display difficult to achieve. The altered meaning of women’s costume in film corresponds with the availability of ready-to-wear clothing, and the desire and ability of costume designers to intervene in fashion retailing. Most recently, as the volume and diversity of commoditised clothing increases, designers find that sartorial choices ‘‘on the street’’ can inspire them, as they in turn continue to shape consumer choice. Introduction Film’s ability to stimulate consumption (responding to, and further stimulating certain kinds of commodity production) has been amply explored in the case of Hollywood (Eckert, 1990; Stacey, 1994). That the pleasures associated with film going have influenced consumption in India is also true; the impact of film on various fashion trends is recognized by scholars (Dwyer and Patel, 2002, pp. -

Ek Paheli 1971 Mp3 Songs Free Download Ek Nai Paheli

ek paheli 1971 mp3 songs free download Ek Nai Paheli. Ek Nai Paheli is a Hindi album released on 10 Feb 2009. This album is composed by Laxmikant - Pyarelal. Ek Nai Paheli Album has 8 songs sung by Anuradha Paudwal, Lata Mangeshkar, K J Yesudas. Listen to all songs in high quality & download Ek Nai Paheli songs on Gaana.com. Related Tags - Ek Nai Paheli, Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Ek Nai Paheli Songs Download, Download Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Listen Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Ek Nai Paheli MP3 Songs, Anuradha Paudwal, Lata Mangeshkar, K J Yesudas Songs. Ek paheli 1971 mp3 songs free download. "Sunny Leones Ek Paheli Leela Makes Over Rs 15 Cr in Opening Weekend - NDTV Movies. The Indian box office is still reeling from Furious 7's blockbuster earnings of over Rs 80 . Jay Bhanushali: Really happy that people are enjoying 'Ek Paheli Leela' It's Sunny side up: Ek Paheli Leela touches Rs 10.5 crore in two days. More news for Ek Paheli Leela Full Movie Ek Paheli Leela - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Ek Paheli Leela is a 2015 Bollywood musical-thriller film, written and directed by Bobby Khan and . The full audio album was released on 10 March 2015. Ek Paheli Leela Online 2015 Official Full Movie | NOORD . 1 day ago - Ek Paheli Leela Online 2015 Official Full Movie; Ek Paheli Leela; 2015 film; 4.8/10·IMDb; Ek Paheli Leela is a 2015 Bollywood musical-thriller . Ek Paheli Leela Full Movie Online Watch Bollywood Full . onlinemoviesgold.com/ek-paheli-leela-full-movie-online-watch- bollywo. -

World Cinema Amsterd Am 2

WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM 2011 3 FOREWORD RAYMOND WALRAVENS 6 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM JURY AWARD 7 OPENING AND CLOSING CEREMONY / AWARDS 8 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM COMPETITION 18 INDIAN CINEMA: COOLLY TAKING ON HOLLYWOOD 20 THE INDIA STORY: WHY WE ARE POISED FOR TAKE-OFF 24 SOUL OF INDIA FEATURES 36 SOUL OF INDIA SHORTS 40 SPECIAL SCREENINGS (OUT OF COMPETITION) 47 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM OPEN AIR 54 PREVIEW, FILM ROUTES AND HET PAROOL FILM DAY 55 PARTIES AND DJS 56 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM ON TOUR 58 THANK YOU 62 INDEX FILMMAKERS A – Z 63 INDEX FILMS A – Z 64 SPONSORS AND PARTNERS WELCOME World Cinema Amsterdam 2011, which takes place WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM COMPETITION from 10 to 21 August, will present the best world The 2011 World Cinema Amsterdam competition cinema currently has to offer, with independently program features nine truly exceptional films, taking produced films from Latin America, Asia and Africa. us on a grandiose journey around the world with stops World Cinema Amsterdam is an initiative of in Iran, Kyrgyzstan, India, Congo, Columbia, Argentina independent art cinema Rialto, which has been (twice), Brazil and Turkey and presenting work by promoting the presentation of films and filmmakers established filmmakers as well as directorial debuts by from Africa, Asia and Latin America for many years. new, young talents. In 2006, Rialto started working towards the realization Award winners from renowned international festivals of a long-cherished dream: a self-organized festival such as Cannes and Berlin, but also other films that featuring the many pearls of world cinema. Argentine have captured our attention, will have their Dutch or cinema took center stage at the successful Nuevo Cine European premieres during the festival. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

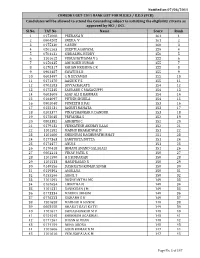

Rank List to Be Published in Web Final

Notified on 07/06/2011 COMEDK UGET2011 RANK LIST FOR M.B.B.S / B.D.S (PCB) Candidates will be allowed to attend the Counseling subject to satisfying the eligibility criteria as approved by MCI / DCI. Sl.No. TAT No Name Score Rank 1 0172008 PRERANA N 161 1 2 0804505 SNEHA V 161 2 3 0175330 S ARUN 160 3 4 0501263 DEEPTI AGARWAL 159 4 5 0704132 SIDDALING REDDY 156 5 6 1101615 PURUSHOTHAMA V S 155 6 7 0150435 ABHISHEK KUMAR 155 7 8 0170317 ROHAN KRISHNA C R 155 8 9 0902487 SWATHI S B 155 9 10 0603497 G N DEVAMSH 155 10 11 0171470 AASHIK Y S 155 11 12 0702583 DIVYACRAGATE 154 12 13 0175345 SAURABH C MASAGUPPI 154 13 14 0603609 ASAF ALI K KAMMAR 154 14 15 0164097 PIYUSH SHUKLA 154 15 16 0902048 PUNEETH K PAI 153 16 17 0155131 JAGRITI NAHATA 153 17 18 0203377 VINAYSHANKAR R DANDUR 153 18 19 0175045 PRIYANKA S 152 19 20 0803382 ABHIJITH C 152 20 21 0179132 VENKATESH AKSHAY RAAG 152 21 22 1101582 MADHU BHARADWAJ N 151 22 23 1101600 SHRINIVAS RAGHUPATHI BHAT 151 23 24 0177363 SAMYUKTA DUTTA 151 24 25 0174477 ANUJ S 151 25 26 0170418 HIMANI ANAND GALAGALI 151 26 27 0602214 VINAY PATIL S 150 27 28 1101590 H S SIDDARAJU 150 28 29 1101533 HARIPRASAD R 150 29 30 0149556 DASHRATH KUMAR SINGH 150 30 31 0159392 AMULLYA 150 31 32 0155266 AKHIL S 150 32 33 1101592 DUSHYANTHA MC 149 33 34 0167654 LIKHITHA N 149 34 35 1101531 RAVIKIRAN J M 149 35 36 0173334 MARINA AKHAM 149 36 37 0176223 RISHABH R K 149 37 38 1201628 MADHAV H HANDE 149 38 39 0603558 BHARAT RAVI KATTI 149 39 40 1101617 SHIVASHANKAR M V 148 40 41 0154545 SHUBHAM AGARWAL 148 41 42 0171261 SUSAN KURIAN 148 42 43 0174159 NEHA ARORA 148 43 44 1101606 ARUN KUMAR N M 147 44 45 1101616 VENUGOPALA K M 147 45 Page No. -

REFERENCES Bharucha Nilufer E. ,2014. 'Global and Diaspora

REFERENCES Bharucha Nilufer E. ,2014. ‘Global and Diaspora Consciousness in Indian Cinema: Imaging and Re-Imaging India’. In Nilufer E. Bharucha, Indian Diasporic Literature and Cinema, Centre for Advanced Studies in India, Bhuj, pp. 43-55. Chakravarty Sumita S. 1998. National Identity in Indian Popular Cinema: 1947-1987. Texas University Press, Austin. Dwyer Rachel. 2002. Yash Chopra. British Film Institute, London. ___________. 2005. 100 Bollywood Films. British Film Institute, London. Ghelawat Ajay, 2010. Reframing Bollywood, Theories of Popular Hindi Cinema. Sage Publications, Delhi. Kabir Nasreen Munni. 1996. Guru Dutt, a Life in Cinema. Oxford University Press, Delhi. _________________. 1999/2005. Talking Films/Talking Songs with Javed Akhtar, Oxford University Press, Delhi. Kaur Raminder and Ajay J. Sinha (Eds.), 2009. Bollywood: Popular Indian Cinema through a Transnational Lens, Sage Publications, New Delhi. Miles Alice, 2009. ‘Shocked by Slumdog’s Poverty Porn’. The Times, London 14 January 2009 Mishra Vijay, 2002. Bollywood Cinema, Temples of Desire. Psychology Press, Rajyadhaksha Ashish and Willeman Paul (Eds.), 1999 (Revised 2003). The Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema. Routledge, U.K. Schaefer David J. and Kavita Karan (Eds.), 2013. The Global Power of Popular Hindi Cinema. Routledge, U.K. Sinha Nihaarika, 2014. ‘Yeh Jo Des Hain Tera, Swadesh Hain Tera: The Pull of the Homeland in the Music of Bollywood Films on the Indian Diaspora’. In Sridhar Rajeswaran and Klaus Stierstorfer (Eds.), Constructions of Home in Philosophy, Theory, Literature and Cinema, Centre for Advanced Studies in India, Bhuj, pp. 265- 272. Virdi Jyotika, 2004. The Cinematic ImagiNation: Indian Popular Films as Social History. Rutgers University Press, New Jersey. -

The Conference Brochure

The Many Lives of Indian Cinema: 1913-2013 and beyond Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi 9-11 January 2014 1 Credits Concept: Ravi Vasudevan Production: Ishita Tiwary Operations: Ashish Mahajan Programme coordinator: Tanveer Kaur Infrastructure: Sachin Kumar, Vikas Chaurasia Consultant: Ravikant Audio-visual Production: Ritika Kaushik Print Design: Mrityunjay Chatterjee Cover Image: Mrityunjay Chatterjee Back Cover Image: Shahid Datawala, Sarai Archive Staff of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies We gratefully acknowledge support from the following institutions: Indian Council for Social Science Research; Arts and Humanities Research Council; Research Councils UK; Goethe Institute, Delhi; Indian Council for Historical Research; Sage Publishing. Doordarshan have generously extended media partnership to the conference. Images in the brochure are selected from Sarai Archive collections. Sponsors Media Partner 2 The Idea Remembering legendary beginnings provides us the occasion to redefine and make contemporary the history we set out to honour. We need to complicate the idea of origins and `firsts’ because they highlight some dimensions of film culture and usage over others, and obscure the wider network of media technologies, cultural practices, and audiences which made cinema possible. In India, it is a matter of debate whether D.G. Phalke's Raja Harishchandra (1913), popularly referred to as the first Indian feature film, deserves that accolade. As Rosie Thomas has shown, earlier instances of the story film can be identified, includingAlibaba (Hiralal Sen, 1903), an Arabian Nights fantasy which would point to the presence of a different cultural universe from that provided by Phalke's Hindu mythological film. Such a revisionary history is critical to our research agenda. -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

Intellectuals and the Maoists

Intellectuals and the Maoists Uddipan Mukherjee∗ A revolution, insurgency or for that matter, even a rebellion rests on a pedestal of ideology. The ‘ideology’ could be a contested one – either from the so-called leftist or the rightist perspective. As ideology is of paramount importance, so are ‘intellectuals’. This paper delves into the concept of ‘intellectuals’. Thereafter, the role of the intellectuals in India’s Maoist insurgency is brought out. The issue turns out to be extremely topical considering the current discourse of ‘urban Naxals/ Maoists’. A few questions that need to be addressed in the discourse on who the Maoist intellectuals are: * Dr. Uddipan Mukherjee is a Civil Service officer and presently Joint Director at Ordnance Factory Board, Ministry of Defence, Government of India. He earned his PhD from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Department of Atomic Energy. He was part of a national Task Force on Left Wing Extremism set up by the think tank VIF. A television commentator on Maoist insurgency, he has published widely in national and international journals/think-tanks/books on counterinsurgency, physics, history and foreign policy. He is the author of the book ‘Modern World History' for Civil Services. Views expressed in this paper are his own. Uddipan Mukherjee Are the intellectuals always anti-state? Can they bring about a revolution or social change? What did Gramsci, Lenin or Mao opine about intellectuals? Is the ongoing Left- wing Extremism aka Maoist insurgency in India guided by intellectuals? Do academics, -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Satya 13 Ram Gopal Varma, 1998

THE CINEMA OF INDIA EDITED BY LALITHA GOPALAN • WALLFLOWER PRESS LO NOON. NEW YORK First published in Great Britain in 2009 by WallflowerPress 6 Market Place, London WlW 8AF Copyright © Lalitha Gopalan 2009 The moral right of Lalitha Gopalan to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transported in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owners and the above publisher of this book A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-905674-92-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-905674-93-0 (hardback) Printed in India by Imprint Digital the other �ide of 1 TRUTH l Hl:SE\TS IU\ffi(W.\tYEHl\"S 1 11,i:1111111,1:11'1111;1111111 11111111:U 1\ 11.IZII.IH 11.1\lli I 111 ,11 I ISll.lll. n1,11, UH.Iii 236 24 FRAMES SATYA 13 RAM GOPAL VARMA, 1998 On 3 July, 1998, a previously untold story in the form of an unusual film came like a bolt from the blue. Ram Gopal Varma'sSatya was released all across India. A low-budget filmthat boasted no major stars, Satya continues to live in the popular imagination as one of the most powerful gangster filmsever made in India. Trained as a civil engineer and formerly the owner of a video store, Varma made his entry into the filmindustry with Shiva in 1989.